The death of Pat Tillman, the National Football League star turned Army Ranger who was killed by friendly fire -- or "fratricide," as the military puts it -- in Afghanistan in April 2004, was a strange event in recent American history. On one hand, Tillman's death was covered far more extensively than those of any of the other 4,700 or so United States troops killed in the Iraqi and Afghan combat zones. To put it bluntly, he was the only celebrity among them.

On the other hand, Tillman's story remains poorly understood and has little social resonance. As a colleague of mine recently put it, Tillman didn't fit, either as a living human being or a posthumous symbol into the governing political narratives of our polarized national conversation. That's true whether you're on the right or the left. If he struck many people at first as a macho, hyper-patriotic caricature -- the small-town football hero who went to war without asking questions -- it eventually became clear that was nowhere near accurate. Yet Tillman was also more idiosyncratic than the equally stereotypical '60s-style combat vet turned longhair peacenik.

Mind you, Tillman might well have become a left-wing activist, had he lived longer. He had read Noam Chomsky's critiques of U.S. foreign policy, and hoped to meet Chomsky in person. But as Amir Bar-Lev's haunting and addictive documentary "The Tillman Story" demonstrates, Tillman was such an unusual blend of personal ingredients that he could have become almost anything. It's a fascinating film, full of drama, intrigue, tragedy and righteous indignation, but maybe its greatest accomplishment is to make you feel the death of one young man -- a truly independent thinker who hewed his own way through the world, in the finest American tradition -- as a great loss.

"The Tillman Story" was made with the close cooperation of Tillman's parents and siblings, who have worked tirelessly over the past six years to expose the circumstances of Tillman's death and the extensive military coverup that followed it. The film is also meant, to some extent, as an antidote to journalist Jon Krakauer's 2009 book "Where Men Win Glory: The Odyssey of Pat Tillman," which the family strongly disliked. (Tillman's widow, Marie, allowed Krakauer to read Tillman's journals, a decision other family members apparently regret.) Bar-Lev's dual goals are to document the family's long crusade to pry the grisly truth about Tillman's death and the ensuing campaign of lies from the military bureaucracy, and, perhaps more important, to capture the unconventional background that produced someone as unusual as Pat Tillman in the first place.

To use the Shakespearean cliché, Tillman was a man of many parts, and that goes back to his childhood in a rural California valley south of San Jose, where his parents, Pat Sr. and Mary, encouraged an almost libertarian blend of self-reliance and free thinking in their sons. (The Tillmans are now divorced, but have worked closely together on the campaign to unpack the military's deceitful behavior.) He emerged as a mixture of qualities that seem simultaneously liberal and conservative, all-American and heterodox. He was a football star and avid outdoorsman who read Emerson; an agnostic or atheist who read the Bible, the Quran and the Book of Mormon out of intellectual curiosity; a man who relished the high-testosterone simulated combat of sports, and excelled at it, while also maintaining an introspective personal journal he allowed no one to read.

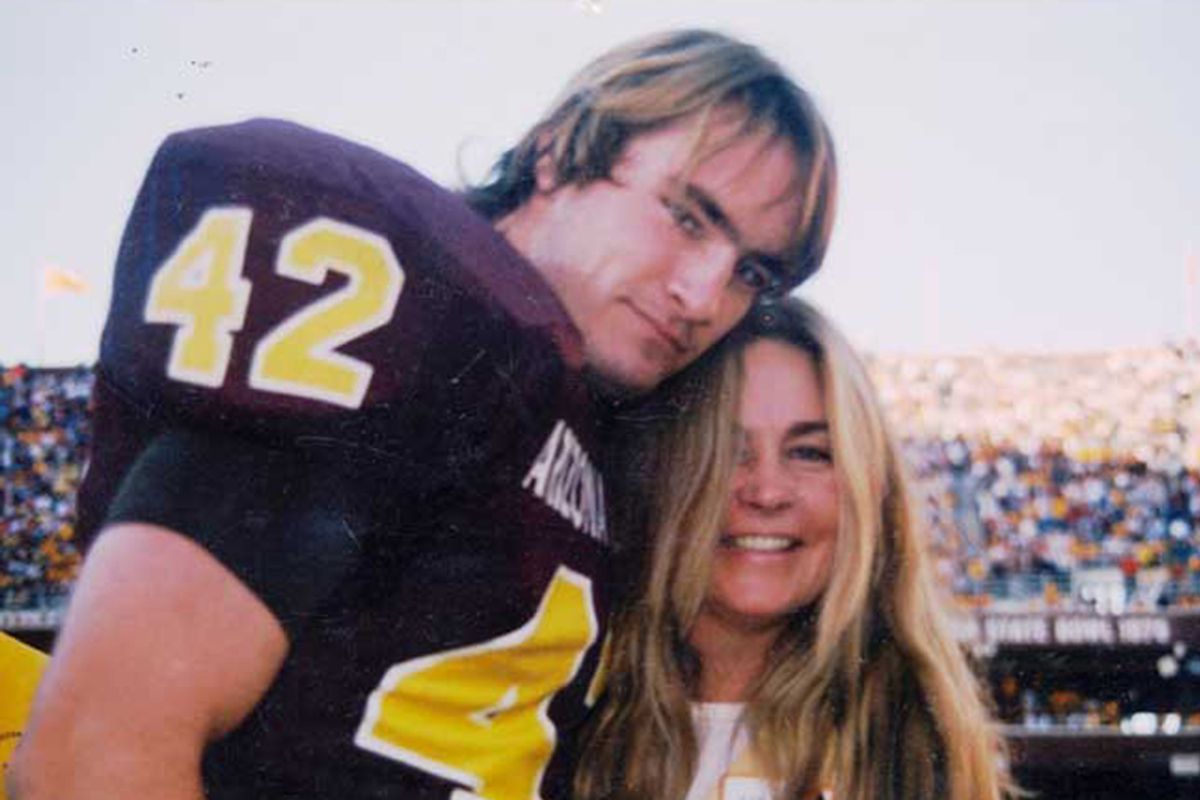

As a friend of mine recently observed, many of Tillman's characteristics would seem completely normal among the metropolitan educated classes: He never went anywhere without a book, and typically rode his bike rather than driving a car. But Tillman wasn't a bearded, chai-drinking grad student riding that bike to yoga class in Brooklyn or Silverlake or Ann Arbor. He was the starting strong safety for the Arizona Cardinals, and parked his bike next to his teammates' Porsches and tricked-out Escalades. Bar-Lev's film is a bit light on Tillman's football career, and doesn't include any interviews with teammates. You have to wonder how much they liked or understood him.

Now you're asking the obvious question: If Pat Tillman was such a smart and interesting fellow, why did he walk away from an easy life of fame and money and volunteer for combat on the other side of the world, where he wound up standing on an Afghan hillside and shouting, "I'm Pat fucking Tillman!" at somebody who was shooting him in the head with a machine gun? There's no easy answer, and in making his film with the Tillmans, Bar-Lev has agreed not to go too far in trying to answer it directly. The Tillman brothers and parents want to respect Pat's refusal to discuss his reasons in public, so the film never quotes from the journals that Krakauer read.

Nonetheless I think "The Tillman Story" and Krakauer's book paint roughly the same picture, in that Tillman's decision to go to war was more personal and philosophical than ideological. He believed that the U.S. was at war after 9/11 -- with Osama bin Laden and al-Qaida, not Iraq or Afghanistan or Muslims in general, Krakauer says -- and decided he had a moral responsibility to take part. He believed in an old-fashioned code of masculine honor and valor, but he had also begun wondering whether his life as a professional athlete was shallow and meaningless. You could almost say he joined the Army in a search for personal meaning and moral purpose.

After serving a tour of duty in Iraq, Tillman returned home with grave doubts about the morality and efficacy of that conflict, and began to make contact with people who opposed the war. (This is the Chomsky-reading period.) Bar-Lev makes clear that Tillman could have asked for a discharge at that point to resume his football career; the owner of the Seattle Seahawks was eager to sign him, and the NFL would no doubt have made a big show of welcoming a returning hero. Again that old-fashioned moral code intervened: Tillman disliked military life and thought the war was wrong, but he wouldn't use his fame to avoid fulfilling his three-year commitment. (He had joined up as an ordinary enlisted man, although he would almost certainly have been given an officer's commission had he requested one.)

I'm only guessing here, but one of the things the Tillman family hated about Jon Krakauer's book was probably the author's tendency to view Pat Tillman's death as a case study in the evils of war and the limits of idealism. I might incline toward that view myself, but the Tillmans don't. Right-wing propagandists quickly learned that the Tillman family wasn't going to stick to the pious, patriotic script. (Pat's drunken younger brother, Rich, at the nationally televised funeral: "Pat isn't with God. He's fucking dead.") But the Tillmans aren't interested in starring in an antiwar morality play either. As they see it, Pat Tillman died as he lived, as an American who thought for himself, hewed to his own course and kept his word. It's the rest of us who have betrayed him.

"The Tillman Story" opens Aug. 20 in New York, Los Angeles and other major cities, with wider national release to follow.

Shares