Darren Aronofsky's psychological thriller "Black Swan," which screened for the press on Friday morning at the Toronto International Film Festival, is one of those movies that demand big adjectives. It's outlandish and melodramatic and spectacular. It aspires to be a 1970s-style event movie, of the kind nobody makes anymore -- a movie that will be chattered about at upscale cocktail parties (the kinds of parties nobody has anymore) and also draw large audiences who just want to be terrified and aroused and told a fantastic story. Set entirely within the cloistered, sadomasochistic world of ballet, it definitely won't be everybody's cup of tea, and those who don't like it can make a great show of being populists bored to tears by the tedious self-involvement of high culture.

But that will not be me. I'm here to tell you that I found "Black Swan's" tale of madness, music and sexual repression utterly overpowering from the first few frames of the film. I forgot about the notebook in my lap and totally abandoned that sense I sometimes get that I'm trying to write the review in my head before the movie's over. I was completely swept up and just wanted to ride along on Aronofsky's hallucinatory journey with Nina Sayers (Natalie Portman), a rising young ballerina who emerges as the star of a leading New York ballet company just as she may also be undergoing a mental breakdown.

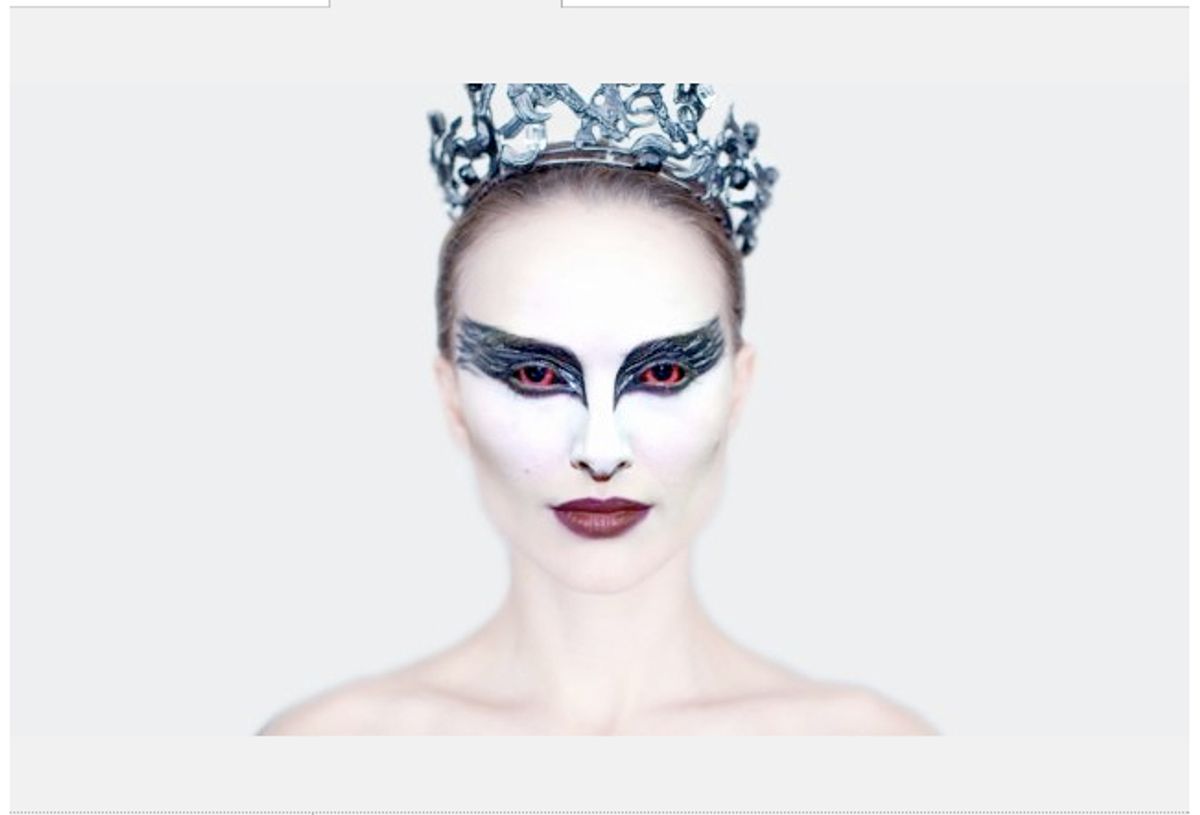

I will happily acknowledge my bias, in that I'm a pretty big ballet fan (although no aficionado) and an even bigger fan of "The Red Shoes," the Michael Powell-Emeric Pressburger masterpiece from 1948 that Aronofsky and his screenwriters (Mark Heyman, Andrés Heinz and John McLaughlin) are echoing or channeling or otherwise not-exactly-remaking here. I'll leave it to genuine balletomanes to judge the quality of Portman's dancing, but I can tell you that she's had solid training and that Aronofsky and cinematographer Matthew Libatique make her look sensational. Or maybe "sensational" isn't the right word; "Black Swan" features some of the most magnificent ballet sequences ever created for cinema, but Nina is supposed to be a dancer whose prodigious technique is a little cold, mechanical and even fearful.

Nina is one of those girls who have been trained for ballet stardom since early childhood, and she has embraced that as her sole purpose in life (since that's the only way you're plausibly going to achieve it). She lives with her archetypal adoring-yet-smothering stage mom (Barbara Hershey) in a small Upper West Side apartment, and she's painfully shy around the other girls in the corps, who have boyfriends and go out to nightclubs and do the other things young women in Manhattan are likely to do. If Nina isn't a virgin, she's doing an awfully good impression of one, and when the wandering eye of company impresario Thomas Leroy (French actor Vincent Cassel, who is superb as usual) alights on her, everyone knows what to expect.

Ambiguous, sexualized master-student relationships abound in the world of dance (not to mention the world, period) but Cassel's character is clearly meant to evoke legendary choreographer George Balanchine, who tended to view the young female dancers at New York City Ballet as his own private hunting preserve. For Cassel's Leroy (as, I believe, it was for Balanchine) it's all part of the artistic process; if Nina is going to dance both the pure and virginal White Swan and the dark, seductive Black Swan in Tchaikovsky's "Swan Lake," she's going to have to learn some things about herself she doesn't know yet. He's just the guy to teach her, of course.

But some strange things happen on the way to what ought to be a simple conquest. For one thing, elevating Nina to prima ballerina means casting aside Beth MacIntyre (Winona Ryder, in a brief but memorable role), who is both the company's reigning star and Leroy's longtime lover. Perhaps deliberately, Leroy also propels Nina into a tense, rivalrous friendship with the company's newest arrival, Lily (Mila Kunis), a tattooed free spirit from the West Coast who lacks Nina's drive and precision but has charisma and sexual energy to burn. And by the time Lily lures Nina away from mom's apartment for a long night of booze, Ecstasy, non-ballet-oriented dancing and some steamy bisexual exploration, we've already cottoned on to the dangerous truth that Nina can't tell the difference between the real world and what's in her head.

Nina has troubling dreams and a history of hurting herself (we gather) and a tendency not to recognize the girl she sees in the mirror. She's haunted by every other woman in the movie -- by her mother, by Beth, by Lily, and especially by the one she sees occasionally on the street or the subway train, the one who looks almost exactly like her. "Black Swan" sometimes has the buzz and chill of a classic horror film, and definitely contains elements of a clinical, Hitchcockian yarn about a nutso girl who damages other people and herself. But there's a lot more heart and beauty to it, a lot more Balanchine and "Swan Lake" and "The Red Shoes," than that description implies.

Aronofsky's fable about Nina's quest to transform herself from the White Swan into the Black Swan captures so much about the physical reality of ballet -- the blood and bruises, the tortured toes and twisted ligaments -- that it feels intimate, sympathetic and even loving. It's a terrible cliché to say that a movie about artistic creation is itself an autobiography of its creator, but this is one of those rare movies in which director, actor, character and story all fuse into a big and powerful allegorical somethingness. "Black Swan" certainly has its flaws -- it's overcooked, and implausible in places -- but I don't care. It's a magnificent blend of pop and art cinema, the breakthrough we've been waiting for from both Portman and Aronofsky, and an instant classic that people will be arguing about all winter.

"Black Swan" will open in theaters in December.

Shares