Joel and Ethan Coen's latest film, "A Serious Man," isn't just unleashing critical plaudits but also a violent wave of high-pitched sissy fights in the nation's A/V rooms, video stores and online magazine offices. The movie geeks of America, you see, are once again forced to grapple with that perennial question: Which Coen film rises above all others?

Before we broke out into our own office brawl, we decided to pose the question to cooler heads whom we also admire. They weigh in below:

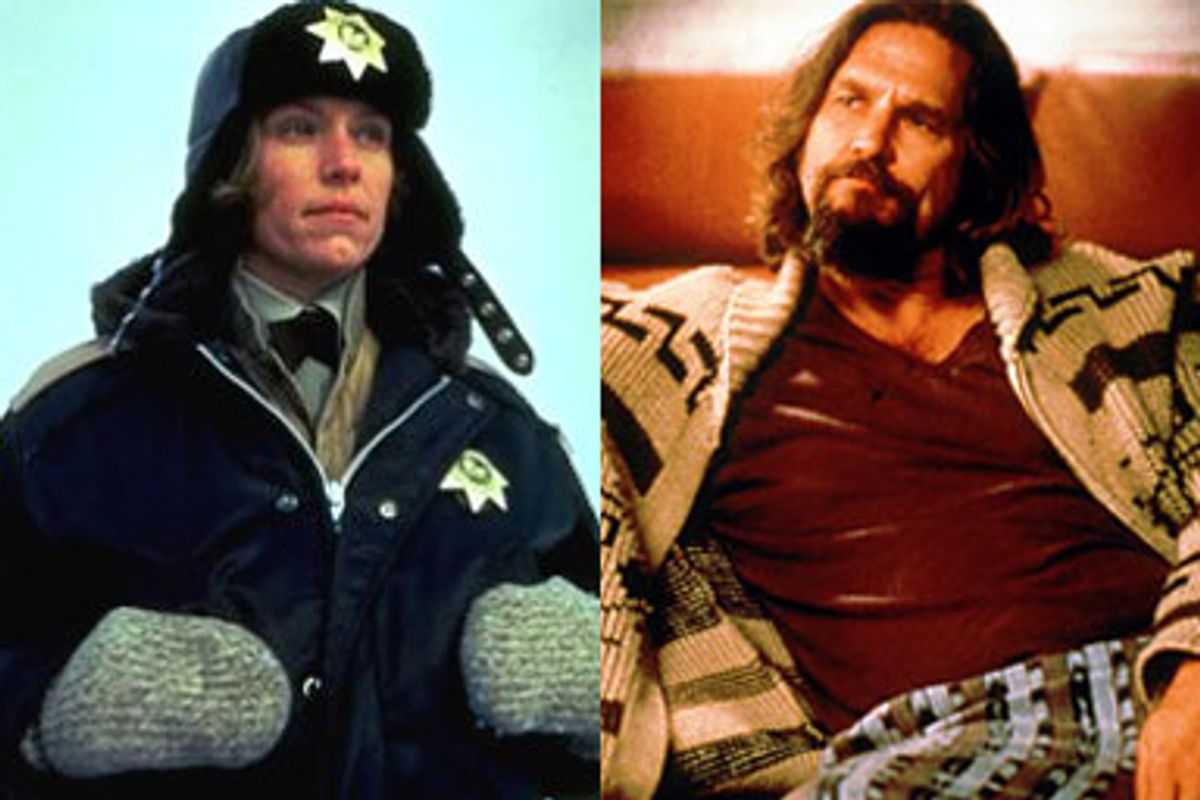

James Toback, director whose most recent film is "Tyson":

The phenomenally talented Coen brothers have yet to make a film without at least some elements of greatness. Their perfect film -- a complete, hilarious and chilling (literally and figuratively) masterpiece -- is "Fargo." If I had to choose a favorite, I would begin by impulsively opting for either "The Big Lebowski" or "Barton Fink" and then end by choosing "No Country for Old Men." This film remains a lean, ferocious and hypnotically inspiring work of art with great performances by Josh Brolin and Tommy Lee Jones and the most exquisitely calibrated representation of evil in the history of cinema by the great Javier Bardem. The film is a permanent resident in the dark imagery of my unconscious.

Mark Cuban, owner of the Dallas Mavericks, 2929 Entertainment and the chairman of HDNet:

The Coen brothers have so many bona fides, it's hard to pick just one or two. "Blood Simple," "Raising Arizona" in the early years, "Fargo" and others in the middle, and "No Country for Old Men" more recently. But I must abide and go with "The Big Lebowski" -- special in so many ways. The Dude epitomizes every guy's dream and nightmare, and we all see some part of ourselves in him: His sense of fair play. His sense of fun and adventure. His honesty. His friendship. Heck, we all want to help our lady friends conceive. But we also all fear that we will end up like the Dude: bowling, driving around and suffering the occasional acid flashback. That's what makes it such a great movie.

Aaron Hillis, film critic for the Village Voice, IFC and GreenCine Daily:

The Coen brothers' earlier movies were instrumental to my budding cineaste education, but up until now, before being asked to seal a favorite in digital cement, I'd have reactively aligned my nostalgia with their more highfalutin pictures -- "Blood Simple," "Miller's Crossing," "Barton Fink." For sheer rewatchability, however, let me come clean and admit that the one that still means the most to me is the first I ever saw: "Raising Arizona." Funny enough, I was raised in Arizona, and I can still remember the 7-Eleven store in Mesa with a few rotating shelves of sun-bleached VHS boxes from where I rented the tape at the ripe age of 10. It blew my mind to see such inventively surreal comedy, from the cartoonish camerawork capturing ex-con Nicolas Cage's kidnapping of a quintuplet, to the miragelike mayhem of Randal "Tex" Cobb's grenade-tossing biker hellion. I find the film even more rewarding on subsequent viewings than the Coens' beloved cult gem "The Big Lebowski," and why isn't Carter Burwell's whistling desert theme considered more iconic?

Mary Harron is the director of "American Psycho," "I Shot Andy Warhol" and "The Notorious Bettie Page":

I have a special fondness for those films that aren't appreciated on their release -- dismissed, underrated -- but whose appeal swells over time. "The Big Lebowski" deserves its fervent cult status, White Russian parties and all. As the now-iconic Dude, Jeff Bridges gives a pitch-perfect performance that is completely free of vanity. He's not a cute faux slob, he's a real slob, with his graying undershirts and slightly delayed delivery, as if all synapses aren't quite firing. I think "Barton Fink" has John Goodman's greatest performance, but his Walter Sobchak -- the Vietnam vet who alternates seething rage with odd moments of political correctness -- comes a close second. And who can forget John Turturro as Jesus, the walking erection in his purple stretch bowling clothes? And finally, like the Dude himself, the film has an essential humanity, a kinder heart than its surface might suggest.

Jeff Lipsky, writer-director of "Flannel Pajamas" and the director of "Once More, With Feeling":

My favorite Coen film remains "Barton Fink," a black comedy containing the best closing shot of any of the brothers' films and more indelible dialogue than I can possibly recount here. From Michael Lerner's studio chief ("Gimme that Barton Fink feeling!") to Tony Shalhoub's head of production ("What do you need? A road map? Talk to another writer. Throw a rock in here, you'll hit one. Do me a favor, Fink, throw it hard"), from John Goodman to Judy Davis, the actors are priceless and perfect.

When Fink, a wunderkind Broadway playwright, is lured away to Hollywood, his hotel room seems a movie set, one in a constant state of being struck. The wallpaper is collapsing, its dripping glue the viscous fixative representing the sexual secretions of the noisy coupling going on in the next room. Fink's eventual hallucinations extend to Gideon's Bible: The only words he's been able to summon replace the opening verse in Genesis. Finally, Fink learns how easy it is to weave a tale, stunning in its simplicity, delicious in its evilness, lavish in its mystery, full of cunning and suspense, and one good, old-fashioned MacGuffin. And all it takes is an anti-Semitic slur to the solar plexus, a bloodthirsty mosquito, and a wave machine known as the Pacific Ocean as inspiration. In 1941 a sneak attack was launched against a New York writer named Barton Fink, it just didn't get much play in the papers.

Molly Haskell, film critic and the author of "Frankly, My Dear: 'Gone With the Wind' Revisited":

I feel almost as inarticulate as poor Ed Crane (Billy Bob Thornton) in trying to describe what it is that gets to me about this strange (and notably unsuccessful), slow-moving crime movie from the Coen brothers. Thornton is the barber of Main Street (the town is Santa Rosa, Calif.,: James Cain meets "Shadow of a Doubt"), a moody passive outsider who's trying to move up or sideways or somewhere in the rush and bustle of postwar America. The movie's beautiful and weird, the elegant high-contrast black-and-white photography plays mocking counterpoint to muddled Ed, a man with a metaphysical bent. While manning the second chair, he speculates on hair growth and sees into the heart of darkness, or at least the whorl of unstoppable life that hair represents. For all the Coenesque eruptions of geeky irony and deadpan blather, it's the fate of this ordinary man that moves me. His somber plight is enlivened by a first-rate cast, not just the wife played by Frances McDormand, but a host of actors on the verge of big-time recognition: James Gandolfini, Tony Shalhoub, Scarlett Johansson, Richard Jenkins.

Scott Burns, screenwriter whose most recent film is "The Informant!":

I grew up in Minnesota and attended the same Hebrew School as Joel and Ethan. (I doubt any of us can actually speak a sentence of Hebrew.) We all ate at the same restaurants, bought cars at the same dealerships and wandered around in the same graying snow drifts. When I first saw "Fargo," I thought someone had broken into my brain and removed scenes from my childhood -- and my sense of foreboding about things like wood chippers. It was funny and frightening and strange and poignant: It was Minnesota. I was certain that only about 15 other people would understand the movie because of the specificity of place. And yet, it is exactly their attention to place that makes "Fargo" so remarkable. Other people do connect. Because detail is so much of life -- all lives. And it is the realization that details will haunt us, kill us and save us that makes me love "Fargo" slightly more than all of their other movies.

Glen Kenny, former film critic for Premiere, blogs about film at "Some Came Running":

It’s boring to cite "The Big Lebowski" as a favorite Coen brothers movie, but I’ve got an excuse: I loved it before you did. I got to see it pretty well in advance of its March ’98 release date: I was working at Premiere at the time, although not yet writing film reviews there. In any event, I went to a screening with some colleagues, pretty much all of whom emerged confused. The general consensus was: “This weird indulgence? After the magnificence and ...” (and here comes that now-common buzzword, the shibboleth that’s dogged the Coens ever since) "maturity of 'Fargo'?” For me, the freewheeling film was an exhilaration. Bowling, Chandler lifts, musical numbers, dream sequences, fabulous color; it was like some stoned reimagining of the Powell/Pressburger ethos. I retain bragging rights with the half-dozen pals I saw it with that I was the only one who actually got it.

Ted Hope is a producer whose most recent movie is "Adventureland":

It's a testament to the Coens that whatever year you ask what movie of theirs is my favorite, I would have a different answer. "A Serious Man" now reigns, as it so captures the joke of our lives (which happens to also be the joke of our business): There is just enough order, symmetry and coincidence among all the chaos for us to will that there is meaning and selection, but alas ... It’s always only what we make of it, isn’t it?

Our folly in our eternal pursuit for answers is hilarious, but the Coens are among the few that give us enough hope to hang our collective souls. I find this predicament hilarious, and with "A Serious Man" they orchestrate it with so many riffs, with both harmonic and dissonant notes, and climaxes in the most surprising of places. The glory of all Serious Men is their folly. “When truth is found … to be lies! And all the joy within you dies! Don’t you want somebody to love?”

Shares