Other people, so I have read, treasure memorable moments in their lives: the time one climbed the Parthenon at sunrise, the summer night one met a lonely girl in Central Park and achieved with her a sweet and natural relationship, as they say in books. I too once met a girl in Central Park, but it is not much to remember. What I remember is the time John Wayne killed three men with a carbine as he was falling to the dusty street in "Stagecoach," and the time the kitten found Orson Welles in the doorway in "The Third Man." -- Walker Percy, "The Moviegoer" (1961)

The poignancy of that quote comes from the implication that the novel’s hero, Binx Bolling, is so alienated from his existence that films feel more real to him than life. But certain filmmakers -- I call them sensualists -- go Walker Percy one better. Through boldly expressive shots, cuts, sound cues and music, they suggest that we experience movies as moments because we experience life that way, too.

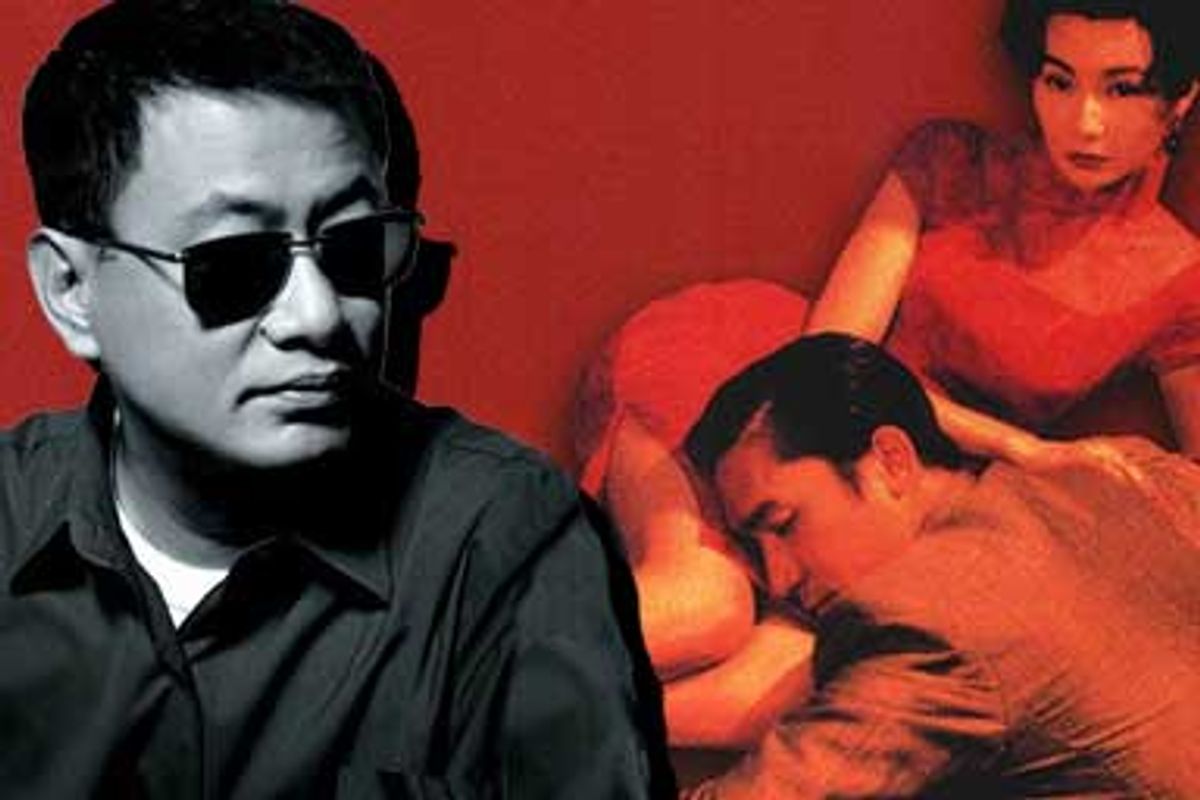

Michael Mann, Terrence Malick, David Lynch, Wong Kar-wai and Hou Hsiao-hsien -- the decade’s great sensualist filmmakers -- accept this proposition as a given. Read a cable channel's one-paragraph schedule-grid summary of Mann’s "Ali," "Collateral," "Miami Vice" and "Public Enemies"; Malick’s "The New World" (all three versions, each of which is a different and equally valid film); Wong’s "In the Mood for Love," "2046," "The Hand" (a segment of the omnibus "Eros") and "My Blueberry Nights"; Lynch’s "Mulholland Drive" and "Inland Empire," or Hou’s "Three Times" and "Millennium Mambo," and you would never guess that the films’ directors had anything in common.

But they share a defining trait: a lyrical gift for showing life in the moment, for capturing experience as it happens and as we remember it.

The sensualists are bored with dramatic housekeeping. They're interested in sensations and emotions, occurrences and memories of occurrences. If their films could be said to have a literary voice, it would fall somewhere between third person and first -- perhaps as close to first person as the film can get without having the camera directly represent what a character sees.

Yet at the same time sensualist directors have a respect for privacy and mystery. They are attuned to tiny fluctuations in mood (the character's and the scene's). But they'd rather drink lye than tell you what a character is thinking or feeling – or, God forbid, have a character tell you what he's thinking or feeling. The point is to inspire associations, realizations, epiphanies -- not in the character, although that sometimes happens, but in the moviegoer.

You can tell by watching the sensualists' films, with their startling cuts, lyrical transitions, off-kilter compositions and judicious use of slow motion as emotional italics, that they believe we experience life not as dramatic arcs or plot points or in-the-moment revelations, but as moments that cohere and define themselves in hindsight -- as markers that don't seem like markers when they happen.

The major phases of the hero's life in "2046" are circumscribed by the time he spent with a handful of lovely and amazing women, but he doesn't know this until he's reminisced; the film is itself an act of remembrance, a transcription of the contents of the hero's head. Wong's sublime re-creations of moments from each relationship have the elasticity of memory; Wong takes his cues from the hero's emotions, stretching or compressing time depending on whether the hero wants to gloss over a moment, scrutinize it or revel in it. Similarly, Pocahontas' life in "The New World" can be subdivided into birth/childhood (distilled into shots of Powhatans swimming in the ocean, then rising to the surface), the pre-John Smith years, the John Smith years, the life-after-John-Smith years, the heroine's marriage to John Rolfe and assimilation in England, and her death. The last event symbolically returns Pocahontas' spirit to its origin point in tandem with the ship that brings her son and husband to North America. The ship is photographed against bright sky that turns it into a cut-paper silhouette -- an iconic image that evokes the ferryman's boat crossing the Styx.

None of these associations or delineations jump up and announce, "Here I am!" while you're watching "2046" or "The New World" -- or "Miami Vice" or Hou's "Flight of the Red Balloon" -- for the first time. The films give you the pieces. You put them together. Sensualist films are composed of moments and fragments of moments -- bits of journeys, traumas, arguments, separations, romantic interludes; mysterious yet evocative shots of buildings, clothes and objects; images that seem like dream fragments, but which you're reluctant to classify as such because the whole film has a dreamlike feel. The fragments cascade across the screen. They don't reveal their significance until you've contemplated the whole film afterward -- and then only if you've reimagined the fragments not on your terms but through the eyes of the films' spiritually questing heroes. (The yearning, sometimes purplish voice-over monologues in Malick's last two films are all about trying to define the indefinable, describe the indescribable. They're about the inadequacy of words.)

Sensualists excel at composing images and moments that seem to stand apart from the films and be about nothing but their own beauty. Yet when you look at such images and moments in the context of the film as a whole they seem hugely significant, because they distill the film's preoccupations with haiku-like precision.

The shots of flowing waters and tall trees that end "The New World" aren't just pretty images of nature; they suggest the ebb and flow of personal and national history (the water) and the way that individual lives (the trees) derive nourishment from it and then root themselves in the memories of loved ones. Early in Wong's "In the Mood for Love," there's a shot of the married heroine, Su Li-zhen, briefly crossing an empty room dominated by a door frame. We don't get a good look at any part of her except her hand, which hangs briefly on the door frame before she leaves the room, and after she's gone, Wong holds on the empty frame. Like the final montage in "The New World," that shot from "In the Mood for Love" seems affected, pretty for the sake of prettiness, until you realize that the film tells the story of two married people who fall in love with each other's spouses. The most important thing in the shot is the wedding ring on the heroine's finger. The brevity with which it appears and disappears in the shot (maybe two seconds) tells you everything about these characters, this story, this director.

The sensualists are sometimes rapped as navel-gazers -- filmmakers who spotlight the ephemeral while ignoring or downplaying the basics: what happened, to whom and to what end. And their kind of filmmaking is not a route to box office glory. Hou is virtually unknown to American moviegoers; his films get brief theatrical releases, often on the coasts, if they play here at all. Wong is better known, but by the standards of Hollywood filmmaking still a curiosity. His great works of the past decade were probably seen by fewer people than saw "Live Free or Die Hard" on opening day, and his first English language feature, 2008's "My Blueberry Nights," was deemed a disappointment by U.S. critics – a misstep that prompted disillusioned fans to revisit his earlier Chinese movies and ask if they were as wonderful as they seemed or if they were graded on a curve because they weren't in English. ("My Blueberry Nights" is indeed minor Wong, small in scale and light in tone, but it's still major; it's the film equivalent of a great symphony composer dropping into a nightclub one Friday night and sitting in on piano.)

David Lynch is a brand name, a synonym for "weird," but he hasn't made a commercially successful film since 1999's "The Straight Story." His two masterpieces this decade, 2001's "Mulholland Drive" and "2006's "Inland Empire," induced rapture among certain cinephiles but bafflement among casual moviegoers. They continued the off-putting arc of Lynch's career, post-"Twin Peaks," which saw the director grow increasingly unsatisfied with merely being surreal and subversive, instead actively undermining, even attacking, narrative itself. Lynch's last three features (including 1996's "Lost Highway") are the closest viewers may ever come to having someone else's dream. The films change emphasis and direction and fuse (or swap out) characters without warning. They flow through the mind like water.

Michael Mann's only hit this decade was 2004's "Collateral," a thriller that was technically innovative (and sometimes eerily beautiful) but structurally tame. His other films -- the 2001 biopic "Ali," 2006's "Miami Vice" and this year's "Public Enemies" -- were in every way more adventurous; they met with wildly mixed, often harsh reviews, made squat at the box office and were derided by many viewers as obscure, meandering, indulgent and worst of all, artsy. Those words were likewise applied to Malick's "The New World," a film that has grown in popularity since its 2005 release, but which is still viewed (like Malick's other films) skeptically by those who distrust movies that aren't fueled by plot -- particularly films that show characters interrogating themselves via internal monologue and turning cartwheels in the grass. "What's the point of such silliness?" the skeptic grouses. "Let's get on with the story. Let's hear it for the good old missionary position."

Then again, let's not. To Binx Bolling's images of Orson Welles in the doorway and John Wayne in the street, let's add the ones cited above, plus more culled from a decade's worth of great sensualist filmmaking: the hero and heroine of "In the Mood for Love " passing each other on the stairwell and feeling the charge of forbidden attraction; the transitions to the neo-noir "future " in "2046" that reveal a sleek elevated train system, a special effect rendered so simply, even crudely, that it's unconvincing, yet which is somehow more dreamlike, more powerful, because it's unconvincing; the demon-man behind the dumpster in "Mulholland Drive," and the rabbits on the couch and the tiny couple and the heroine's nonsensical, nightmarish rushing-about in the disorienting final sequence of "Inland Empire"; the shock cut that reveals the black-painted Death figure sitting in the chair near Pocahontas' bed in "The New World"; the Holly Golightly-esque heroine of Hou's "Millennium Mambo" standing up through an open car roof as she rides through a tunnel at night, arms out, grinning, techno pulsing on the soundtrack; the shots of lovers' hands tentatively touching for the first time in Hou's 2005 triptych of shorts "Three Times." Of the latter, Salon's Stephanie Zacharek wrote, "Hou is less interested in strictly defined plots than he is in mapping the way time unfolds, exploring the varied, shifting textures of the hours of the day as they move along."

Mann, maybe the best-known practitioner of this type of filmmaking, produced countless indelible sensualist moments in the past decade. My favorites include Muhammad Ali sitting by himself in a subway car at night in "Ali," contemplating his true self before he steps into the ring or on TV and shows the world his constructed self; the assassin and the cabbie in "Collateral" watching a coyote lope across a Los Angeles street; the high-angled shot of Crockett and Isabella sailing to Cuba in a go-fast boat in "Miami Vice," and the subsequent cutaway, during their conversation in the bar, to a shot of children's legs running in front of a car's hubcap -- an image that hints at the domestic future that the lovers can't have because they're loners at heart. While we're at it, let's add three images from Mann's uneven but fascinating "Public Enemies": the streetlamps reflected in the hood of John Dillinger's sleek black car; the granite determination in the eyes of lawman Charles Winstead as he interrogates Dillinger's girlfriend, Billie Frechette, and his bemused respect as he realizes she's tougher than he thought; and Dillinger's awed and amused expression as he watches "Manhattan Melodrama," seeing his reality in the film's fiction, finding himself in the moment.

Commitment to the moment is the reason Mann's camera in "Miami Vice" creeps so slowly toward the face of drug cartel henchman Jose Yero as he watches Crockett and Isabella dance in a nightclub and realizes from their body language that they're not just having sex, they're in love. The moment isn't just about Yero realizing that Isabella's judgment and the security of his boss's operation have been compromised; it's about Yero's humiliation and rage at realizing that Crockett has won the heart of a woman who would never give Yero the time of day. Most filmmakers would duly note Yero's epiphany and get on with it. Mann stays inside the moment as long as he can, feeling Yero's rage build and crest like a wave. Yero's feelings are the point of the scene, just as the "Mulholland Drive" lovers' scorching desire to lose themselves -- their very identities -- in a moment is the point of the first lesbian tryst in Lynch's film, and just as the experience of being John Dillinger is the point of that sequence in "Public Enemies" where the gangster brazenly walks into a police station, looks at the evidence laid out against him on a squad room wall, and sees himself as others see him -- as a legend, a menace, an abstraction.

Village Voice critic J. Hoberman nailed the sensualist ethos in his review of Hou's 2007 reimagining of the classic French short "The Red Balloon" when he described Hou's version as "a movie that encourages the spectator to rummage ... contemplative but never static, and punctuated by passages of pure cinema. A medley of racing shadows turns out to be cast by a merry-go-round. A long consideration of the setting sun as reflected on a train window that frames the onrushing landscape yields a sudden flood of light."

In a sensualist film, the shape, color and pace of the world on-screen is informed, sometimes formed, by what the characters are feeling -- and by the filmmakers' determination to present those feelings as vividly and cinematically as possible. Which necessarily means that sensualist films often disregard or downplay elements that "good" movies are expected to prize: snappy dialogue; a three-act structure with a cause-and-effect plot that "raises the stakes," as hack screenwriters say, every 20 minutes or so, and a pop-Freudian sense of characterization that shows characters with a single overriding flaw identifying the cause of that flaw (moral compromise, a grim childhood) and struggling to heal, or win, or whatever. You know -- the shopping list.

Sensualists have no use for lists. They flip them over and write poetry on the back. They're quite comfortable with viewers asking, "Why did the character decide to do that?" or "Why did the film end where it ended?" or "What is this movie trying to say?" In fact, the opportunity to provoke such questions is a big part of why they make films. They want to spark identification and subjective response. They want to put you inside another time, another place, another life.

Thanks to Sarah D. Bunting and Aaron Aradillas for their invaluable assistance with this series.

Shares