Michael Moore is the only documentary filmmaker besides Ken Burns the average American has heard of, and he’s more of an active presence in American life than Burns, because even when he's not making or promoting a new film, he's on TV and the Internet beating the drum for a cause or tormenting the foes of all he deems good and decent. He is a media-age phenomenon as well as a filmmaker, his presence on the pop culture radar screen a life-as-mass-media-performance-art-project in the vein of previous practitioners, some important, others merely shameless: Andy Warhol, Muhammad Ali, Madonna, Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal, Tiny Tim.

And whether you think Moore is a brave soul fighting the power or a self-aggrandizing blowhard who’s mainly selling himself, it’s clear he has a knack for insinuating himself into the head space of all sorts of people -- those who have no opinion on him, those who are glad he’s alive, and those who fantasize about pouring a vat of beef stew over his head and tossing him into a pit full of wolverines. I suspect Moore’s highly subjective, emotion-driven filmmaking and his career-long interweaving of self-promotion and self-expression (which started back in 1989 with his anti-General Motors jeremiad "Roger & Me") will one day be seen as epitomizing aspects of life in this grim, weird decade, just as Hunter S. Thompson’s song-of-myself political writing helped future generations understand the '70s.

When artists construct such a compelling public face, the art and the artist fuse, even loop back on themselves so that it's tough to tell where one begins and the other ends. It's a conundrum the modern artist can't escape, and maybe shouldn't; when an artist resists becoming the story, the media and the public tend to decide there isn't one. Moore knows vastly fewer people would talk about his movies, or even bother to see them, if he weren't out there on talk shows and in front of his own documentary lens raising hell, cracking wise, taunting the powerful, comforting the powerless and otherwise carrying on like the bastard spawn of Will Rogers and Amy Goodman.

In any event, Moore the director has been politically and artistically (and on the Internet, technologically) vital -- not to mention adept at identifying subjects of mass dread and getting films about them into the marketplace right around the time said dread achieves critical mass. In the last 10 years, Moore has addressed the self-perpetuating cycle of fear and violence in America ("Bowling for Columbine"), the Bush administration's conduct of the war on terror (“Fahrenheit 9/11”) and the arguments in favor of state-run, or at least state-assisted, healthcare (“Sicko”).

Moore's latest, "Capitalism: A Love Story," might be the key Moore film, its title serving as an umbrella that shades every other subject he's tackled. The answer to every “Why?” in a Moore film can be answered, “Because of money.” Its arguments are too fuzzy and its thesis too broad to achieve the level of popular relevance to which Moore has become accustomed; Americans prefer ideas they can hold in their hands. But whatever "Capitalism's" reception, the fact remains that nobody else is making political films on such basic and important subjects and getting them so widely distributed and discussed.

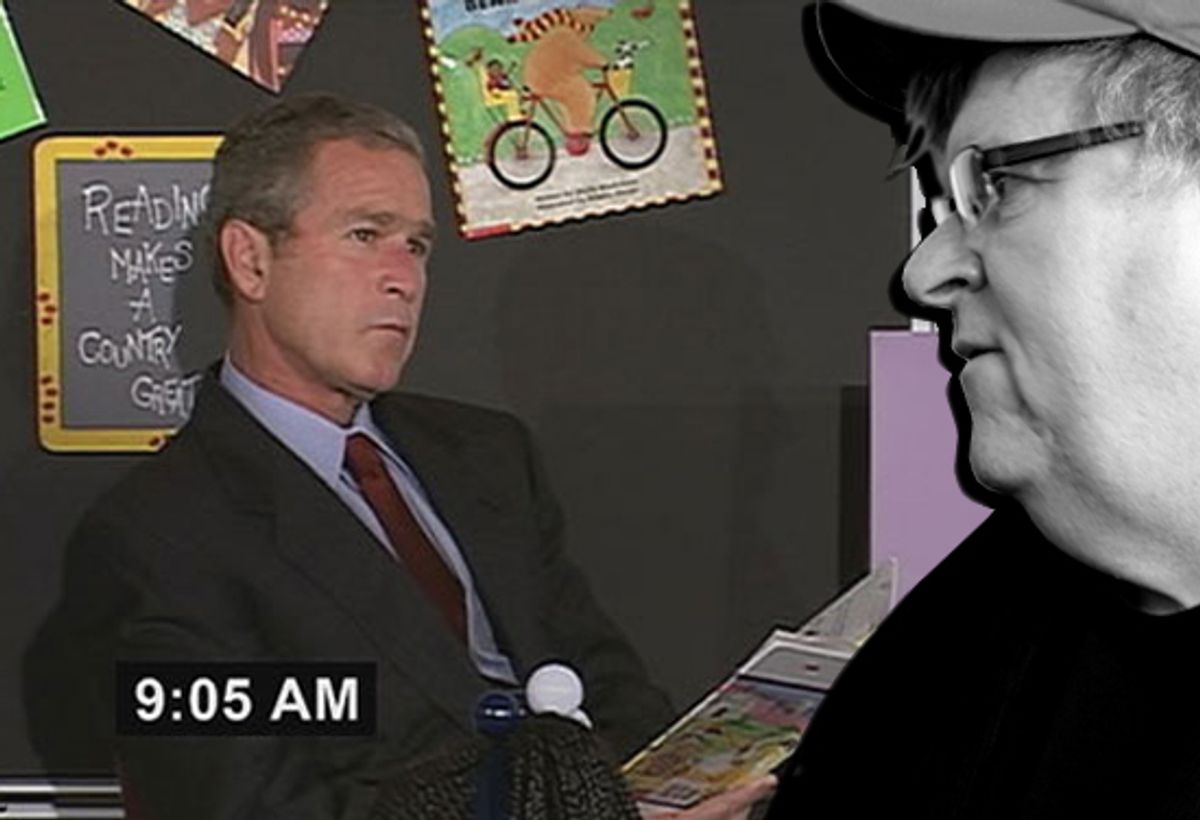

None of Moore's films this decade were as prominent as “Fahrenheit 9/11,” because none had a main character as charismatic and polarizing as President George W. Bush. It was the first feature that Moore tried to stay out of, to the extent that Moore can stay out of anything, and I wouldn't be surprised if his decision was motivated both by a desire to foreground the message rather than the messenger and an entertainer's understanding that you can't steal the spotlight from a child, a pet -- or W. himself. (Add to that the fact that Moore, who positions himself as the good guy in his own mythic narratives, hadn't had a truly intimidating adversary since GM boss Roger Smith.)

The prospect of making the president lose reelection, or at least lose sleep, formalized the (often contrived) underdog mantle that Moore has always wrapped around himself like a cape. And it encouraged Moore to spotlight his insult comic's vicious wit, setting one of the movie's expository passages about the president's youth to Eric Clapton's "Cocaine" and letting Bush's paralysis in that classroom on the morning of 9/11 play out at length. One rarely sees a documentary whose whole purpose is to tear down another person, and that dubious distinction made "Fahrenheit 9/11" electrifying -- if only to liberals who felt helpless in the face of the president's political, military and media machines and prayed that somebody somewhere would stand up, say something, do something.

Bush's brazenness post-Iraq seemed to crank up Moore's urgency and grandiosity. Around the time "Fahrenheit 9/11" came out, Moore declared that his goal was nothing less than the electoral defeat -- or re-defeat, as the bumper stickers said -- of the president (whether the film ultimately hurt or helped the president is an important, but unanswerable question). To achieve that end, Moore paints Bush's definitive negative caricature, presenting him as a hateful fraud, an ignorant brat playing with mass-murdering toys, a fake macho man whose cornball swagger was purchased with daddy's money and America's military might, and a bumpkin prince of darkness whose descent upon the Capitol following the electoral shenanigans of 2000 was a metaphysical as well as political catastrophe. And the film's opening credits are one of the decade's most powerful sequences: Bush and his Cabinet being made up for TV appearances while mournful, minor-key acoustic guitar plays in the background is a devastating marriage of image and sound, one that conjures sadness, rage and fear. The sequence is a liberal's dirge. Democracy is dead, and here are its murderers putting on their war paint and getting ready to finish off the rest of us. (Facing down the president ennobled Moore's asshole tendencies. His adversary was so powerful and so smug about his power that Moore couldn't go too far in attacking him – at least not as he did in “Bowling for Columbine,” in which he trespassed on the property of the elderly, unprepared and clearly baffled NRA spokesman Charlton Heston and answered his gentlemanly incredulity with snotty contempt.)

"Fahrenheit 9/11" was arguably the documentary of the decade, a work that tried to change history as well as describe it and, if not a classic of logical argument, then surely a masterpiece of outrage, propaganda as formally skillful as it was emotionally opportunistic. (Moore's use of war veterans and their loved ones was the liberal flip side of W. treating uniformed soldiers as TV props to burnish his warrior bona fides.) And it was everywhere in 2004 -- in theaters, on TV, on the Web. Even if you hated Moore's guts and wouldn't see the movie if your life depended on it, you still ended up reading about it, hearing the film's merits argued and its errors and distortions catalogued. Moore shows the world what American liberal anger looks like -- a furious but ephemeral force that rarely stays roused for long, liberals being notoriously inclined to bitch rather than act unless it's a presidential election year. Elsewhere this decade he prided himself not just on participating in the national argument, but also on setting its terms. His films supplied liberals with talking points on gun violence, 9/11, the war on terror, healthcare and financial chicanery. His Web site, public speeches and coordinated e-mail campaigns endorse or oppose presidential decisions, political candidates and propose new laws. (Moore's "Letter From Mike" feature is written, quite effectively, in the jes' folks style of his movie narration. "It's not your job to do what the generals tell you to do," Moore writes, in an "open letter" to President Barack Obama urging him not to add more troops in Afghanistan, adding, "With our economic collapse still in full swing and our precious young men and women being sacrificed on the altar of arrogance and greed, the breakdown of this great civilization we call America will head, full throttle, into oblivion if you become the 'war president.'" For better or worse, Moore is one of a few filmmakers who could publish such a letter and rest assured that a president (or his people) might even read it.

He's the enemy the right deserves and probably craves. He is his own self-caricature, and craftier and more gifted than detractors care to admit. He's a standard-bearer in the rhetorical civil war that Mailer, in 1963's "The Presidential Papers," foretold as inevitable fallout from the end of the Cold War -- "the war which has meaning, that great and mortal debate between rebel and conservative where each would argue the other is an agent of the Devil."

Shares