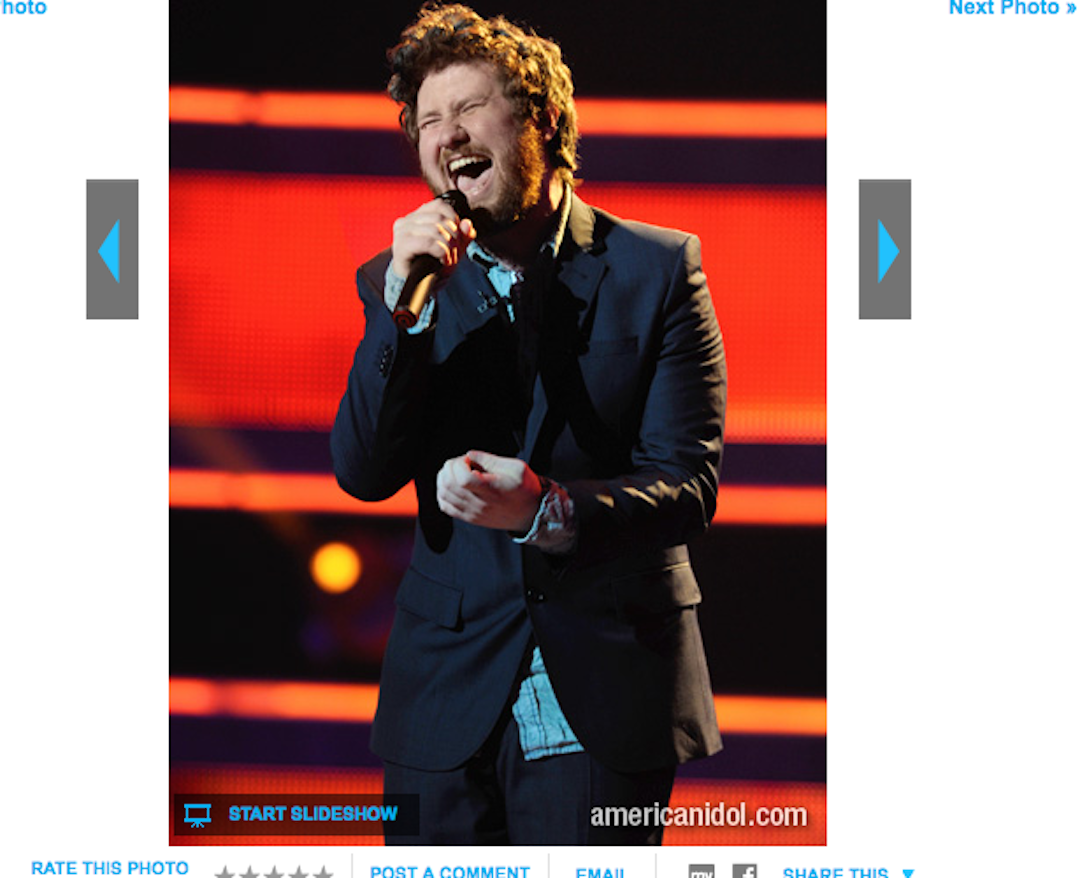

Casey Abrams stands on the “American Idol” stage, belting out a Nirvana classic. On the other side of the country, in a tiny New York City apartment, three females sit in front of the television, feeling stupid and contagious. My 11-year-old, Lucy, is zonked out on Benadryl, still reeling from the aftereffects of an allergic reaction to an antibiotic that landed her in the emergency room two weeks ago. My 7-year-old daughter, Beatrice, and I, meanwhile, have mostly rallied from the case of strep that hit us both a few days ago, but each painful swallow reminds us that neither of us will be hitting any Thia Megia-level high notes any time soon. We concur that James is a dead ringer for daddy. We argue passionately about the merits of Paul over Stefano. We are outraged when the adorable Latina girl from our own neighborhood, Karen Rodriguez, gets the boot. And we irrationally loathe Scotty, because loathing the cancer that’s rapidly robbing the girls of their grandfather won’t make a lick of difference. We don’t just love “Idol.” For two hours a week, we need it. Desperately.

For nearly a decade, my children and I managed to successfully avoid the brunt of “Idol.” We generally don’t watch television at night, anyway, and when we do, the occasion is far more likely to be a movie or special event than a competition. But when a casual curiosity about the new judges Steven Tyler and Jennifer Lopez piqued our interest a few weeks ago, the kids and I found ourselves sucked, instead, into the drama of aspiring Idols themselves. Timed as the show was to our own crush of illnesses, middle school interviews, and devastating losses, it rapidly became a cathartic outlet for an unprecedented torrent of emotions.

And so here we are again, another Wednesday, ready to flop together on a pile of pillows on the floor, exhausted at the end of another grueling day, because this goofy, decade-old singing contest has become the unlikely bright spot in a Martius horribilus. A few towns over, Jeff sits exactly where he’s been the past two weeks, watching one tube drip morphine into his father’s veins as another drains the brown and green fluid from his insides into the carafe at his bedside. In Rochester, the family prepares to bury the uncle who slipped away peacefully last Saturday morning. In Philadelphia, one of my best friends, the one I had to cancel plans to visit this weekend when all the crap hit the fan, dashes off a supportive email — and a photo of her chemo-smooth head. But right here, right now, all that matters in the world is whether Naima can nail it — and what crazy thing Steven has to say about it.

It’s not just that the fluff of “Idol” is a welcome respite from the far more serious woes that currently bedevil us — although it is. It’s hard to feel completely sad when Randy is calling someone “dog.” But in its surprising, strange way, the show has become a reflection of our own family struggles. We watch, riveted, because that guy who looks like Yukon Cornelius has dreams and disappointments and sorrows. Because we are trying so hard to be gentle with each other most of the time that it feels terribly important — and really good — to fight about whether Haley is awful or awesome. And because every schmaltzy, overblown rendition of a song that would otherwise make us roll our eyes can bring us to welcome, necessary tears after surviving another anguished day of paying the bills or rehearsing for the school play. At 2 in the afternoon, we can’t break down. But at 8:30, we’ll find ourselves laughing at our own lameness while we’re sobbing our hearts out over Jacob Lusk’s rendition of “Alone.” We’ll dance around the living room in our pajamas, like a scene out of some awful Hallmark movie, rasping along with Paul and mimicking his uniquely uncoordinated dance moves. And it’s the best thing in the world.

My daughters have, fortunately, no real prior experience of loss. The closest thing to grief they’ve ever experienced was when the school guinea pig died in a tragic feeding bottle incident a few months ago. Now, just as they’re both miserable with their own physical ailments, they’re hip deep in emotional pain as well. So I flip them pancakes for dinner and let them stay up past bedtime and write notes explaining why their homework projects will be late, and I hug them tightly and let them crawl into bed with me when they’re scared in the middle of the night. But I can’t give them back the grandfather who taught them to paint on the back porch. I likewise can’t close my eyes and blot out the sight of what the ravages of cancer look like, any more than I undo my own experience of it. I can only let kids vote for Lauren Alaina, because they see in her puppyish exuberance something bright and hopeful that touches them in a way they can’t even articulate right now. I can only explain to them that “If You Don’t Know Me By Now” isn’t just a Simply Red song. I can only make more popcorn.

Last Thursday I went out to the hospice one last time to see the man who has meant more to me than my own father ever did, to hold his hand and kiss him goodbye. And at night, when the girls asked eagerly if it was “Idol” time yet, I felt as happy and relieved to tell them yes as I would be all day. Because as corny and silly as that troupe of aspiring pop singers may be, as dopey as that franchise may seem, right now, they’re our life raft in a sea of hurt. And when my girls and I listen to Pia Toscano sing “Where Do Broken Hearts Go,” it’s like she’s singing just for us.