Fox's "Glee," which ends its first season tonight, is one of the most stylistically bold broadcast network shows since "Twin Peaks." That might seem an unlikely claim on first glance: "Glee" is a feather-light comedy at least 70 percent of the time, and a glib, mannered one at that. From its wistful-kooky incidental music to its subtext-as-text quips (Noah "Puck" Puckerman: "That Rachel chick makes me wanna light myself on fire, but she can sing"), "Glee" is shellacked in cuteness. And its subject matter -- the private and public melodramas of high school students and teachers -- is the stuff that dismissive reactions are made of.

What's radical about the series -- which was created by "Nip/Tuck" mastermind Ryan Murphy -- is its direct, at times nearly primordial sincerity, expressed mostly in its musical numbers. The musical moments seem indebted to English writer-producer Dennis Potter ("Pennies From Heaven"), who used fantasy lip-sync interludes to explore the feelings that repressed middle-class English citizens could not otherwise show. Similar moments on "Glee" stand in opposition to the majority of American popular culture, which fears simple, sincere expressions of feeling the way little boys fear cooties. It also stands in contrast to the rest of "Glee" itself -- a series that, like so many contemporary TV shows and films, is relentlessly arch and shallow, forever strip-mining that bitchy/glib screwball vein that made writer-producer David E. Kelley ("Ally McBeal," "Boston Legal") a multimillionaire, and that Murphy continued in such series as "Popular" and "Nip/Tuck." Surprises are few and far between, unless you count the little ones: wacky costumes, a crueler-than-expected insult, or a stray moment of authentic human contact not mediated by six decades' worth of sitcom and soap opera clichés (the relationship between the gay teenager Kurt and his straight, blue-collar father, Burt, is far and away the most original and affecting subplot).

There has always been an imagination gap between the musical sequences and the rest of "Glee," with its incessant insult humor, "Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids"-style, "Let's all summarize the lesson we just learned" monologues, and sometimes-clever, sometimes-lame metafictional gags (Sue Sylvester narrating her diary entry in voice-over, briefly pausing to note that she's narrating a diary entry in voice-over). That gap became a chasm when the show returned this spring. Between the lather-rinse-repeat mechanics of the "If X doesn't happen, we'll lose the glee club!" device to the bumper crop of recent plots twists that seem nonsensical even by "Glee" standards (perpetually soul-searching nice guy Will plotting to seduce and abandon Sue, for example), the non-musical parts of "Glee" feel like chores that viewers have to plod through to get to the good stuff.

Qualitatively, the musical numbers on "Glee" have always been all over the map, from haunting and beautiful to cruise-ship perfunctory. And yet -- like the mostly trashy, ADD-edited musical numbers in Baz Luhrmann's "Moulin Rouge" and Rob Marshall's "Chicago" and "Nine" -- they still have the power to absorb and transport viewers because they understand the function of musical numbers: to slough off the shackles of "reality" and express and embrace raw, complicated emotions that might be diminished by regular dialogue. The first 13 episodes generated musical/psychological moments of startling power. Although every viewer has his or her own favorites, I'm partial to "Somebody to Love," "Don't Rain on My Parade," "Don't Stop Believing" (which the show managed to reinvigorate yet again, two years after one assumed that it had been stamped "Property of ‘The Sopranos'" and retired forever) and the football field riff on "Single Ladies" (also a great Kurt-and-his-dad moment).

Since coming back from its break, however, "Glee" has brought even more cleverness -- and more undiluted emotion -- to its musical sequences. The paraplegic Artie's fantasy of spontaneously performing "The Safety Dance" in a shopping mall was Dennis Potter-worthy. But it was elevated to another conceptual level through its filmmaking: Halfway through the number we started seeing the performance captured via the rough-and-ready imagery of flip phones, connecting this handsomely produced network series with the YouTube/Facebook/Twitter culture that made it a smash.

The first season's all-around musical high point, though, was the Madonna episode. From Sue's "Vogue" fantasy (playfully re-staging that fabulous Madonna video while letting Sue's neurotic reality intrude) to the cross-cutting between three attempted seductions set to "Like a Virgin," to that pharaoh's army of gospel singers appearing out of nowhere in the "Like a Prayer" finale (a ludicrous-wonderful indulgence in the same vein as that that Busby Berkeley soundstage materializing behind Kate Capshaw in "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom"), the episode kept topping itself. It also boasted the highest music-to-nonmusic ratio of any episode aired to date; long stretches were practically an extended musical fantasia -- a sight rarely seen on American TV, unless you count the occasional sung-through novelty episode of an otherwise traditional show. (The gold standard in that department is "Once More With Feeling," from season six of Joss Whedon's "Buffy the Vampire Slayer." The recent "Glee" guest shot by Neil Patrick Harris, star of Whedon's "Dr. Horrible's Sing-Along Blog," sparked hopes for a similarly rip-roaring, old fashioned musical indulgence; it never quite happened, but that too-short "Piano Man" duet was lovely.)

There have been stinkers, of course; for my money, the worst number since the show's return was the library rampage scored to "Can't Touch This" (an already silly, pointless bit made worse by indifferent choreography and singing). On the whole, though, the best numbers in the freshman season's so-called "back nine" are so unexpected in their conception, and so heartfelt, that they make the rest of the series feel like Will's description of Vocal Adrenaline as "a machine; a collective, synthesized, soulless beat."

The series came back from its break emboldened by positive reviews and a fan base so rabid that it turned the "Glee" live tour into the 21st century version of Beatlemania. Murphy and company had a mandate to swagger, and they did. Their "What the hell, let's try it!" confidence is most vividly expressed in musical numbers that casually blur the boundaries between "reality" and "fantasy" with retro verve.

"Glee" always saw this boundary as somewhat fungible -- witness the never-gets-old running gag of a character telling Will for the very first time what song she's about to perform, whereupon the camera pans to reveal, say, an eight-piece ensemble that includes four Julliard-caliber string players. But the wall was always there. Not so much now, though. The "Like a Virgin" setpiece is one example. It's impossible to justify as any one character's fantasy, unless you buy that all six characters would be thinking of that particular Madonna song at the same time. It seems more like a cousin of that moment in the film version of "West Side Story" that crosscuts between several key characters singing overlapping snippets of the score's most famous tunes. You can't explain it or classify it or explicate it. You just have to accept it and respond to it.

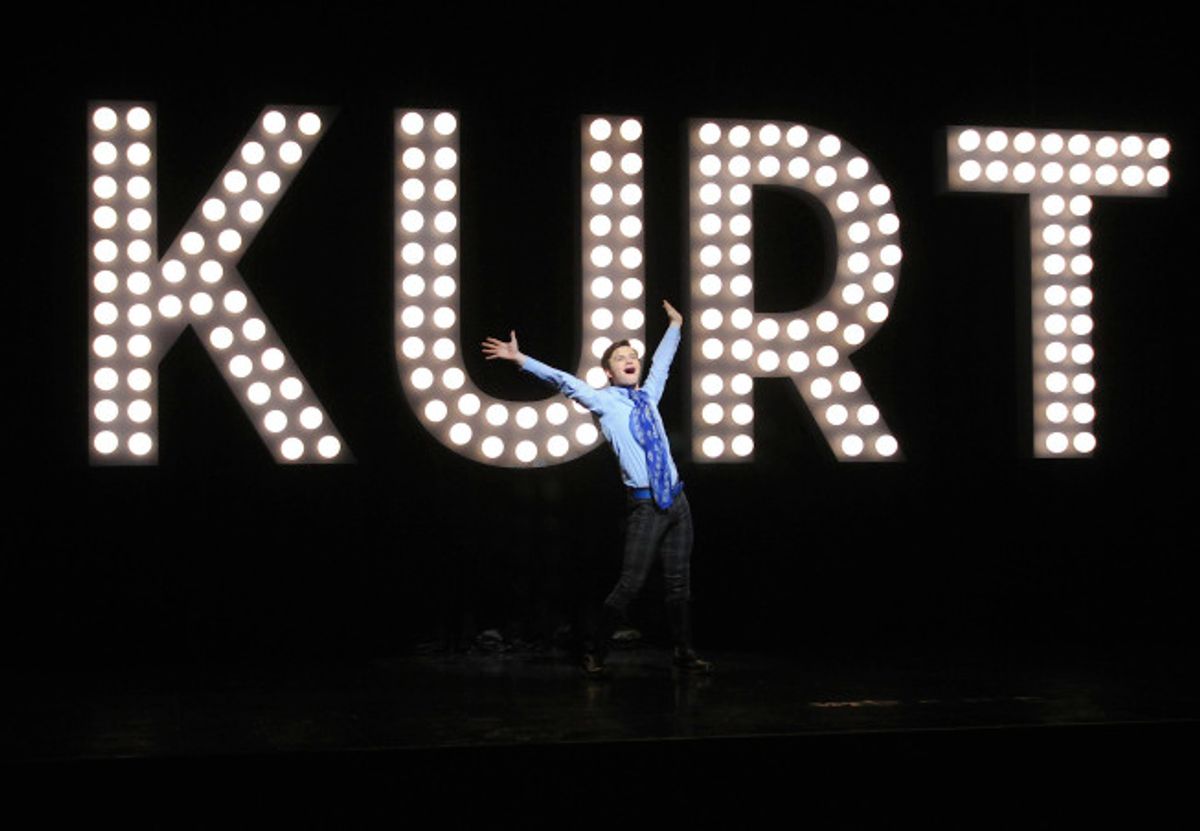

Even better is Kurt's performance of "Rose's Turn" from "Gypsy." It begins with Burt Hummel walking away from his son in a high school hallway, moments after wounding him by revealing that he was about to take Finn (his new girlfriend's son) out for some straight-guy bonding adventures. Reality gives way to fantasy incrementally, almost imperceptibly (Kurt begins singing the song in the hallway, in "reality," and concludes it on a stage backed by his name in lights) and then eases back into "reality" again (Kurt's father, who secretly saw the whole thing, applauds him, and tells him, "That was some serious singing, kid"). The entire sequence occurs in a space that's more psychological than geographical: Music Land.

Moments when a character burst into song without preparation or explanation were common in American popular culture until the 1970s, when the traditional musical began to disappear from movie screens, and the musical variety series faded from TV. It was the moment that prose gave way to poetry, and it's been a tad galling to see supposed "returns" of the musical (Luhrmann, Marshall, even the thoroughly beguiling "Once") bend over backwards trying to justify such moments. (Potter, Bob Fosse and MTV all bear a lot of responsibility for this change, as positively influential as they were in other ways.)

Perhaps the traditional musical moment is a casualty of modern life, which seems increasingly hostile to poetry in all its permutations. We're collectively too damned cool for any form of expression that's directly communicates deep feeling -- with any outpouring of emotion not placed in a context that hangs a label on it and thereby tames it (thus the post-MTV obsession with justifying why characters conceivably might burst into song -- the mania for justifying it as a live performance, or fantasy or whatever).

The culture-wide battle between sincerity and cool is encoded in "Glee" itself. The show's predominant tone is hostile to poetry, to real empathy. For every hug there are five or six pot shots. It grinds the characters down the way the school establishment (epitomized by Sue) grinds them down. It makes fun of them before you can (presuming that you will -- and who says you would?). It spells out every issue and emotion in pop-psych dialogue, and encloses the entire tale within gigantic neon quote marks. The song-and-dance numbers tear down the quote marks like triumphant insurgents toppling the statues of a hated dictator -- and as soon as the music stops, the statues go right back up again. Lather, rinse, repeat.

The great accomplishment of "Glee" is its success at creating a zone where a bomber-crew assortment of contemporary Americans can live, however briefly, without the encumbrance of quote marks, forget context and logic and justifications of any sort, and let rip with a pop smash or a Broadway show tune. The difference between adequate escapist fluff and transcendent popular art is the difference between the moments where "Glee" characters talk and the moments when they sing. When the characters talk, they replicate faddish modes of expression and sound like what they are: stereotypes of one kind or another, slaves to commerce doing and saying whatever the show's writers need them to do and say at any given moment. When they sing, they assert their uniqueness, their bravery, their indestructible purity of heart.

Shares