In the wake of the Food and Drug Administration's recent approval of the abortion drug RU-486, there were familiar arguments about a woman's right to choose vs. the unborn child's right to life, as well as speculation about ways in which the drug would change the terrain of the abortion wars. As usual, though, these discussions completely ignored one group of people who still have no legal voice in decisions about having -- or not having -- children.

They're called men.

It is widely assumed by activists on both sides of the debate that legal abortion puts women on equal footing with men, giving them the same freedom to enjoy sex without consequences. Actually, when sex results in conception, the man and the woman find themselves on very unequal footing.

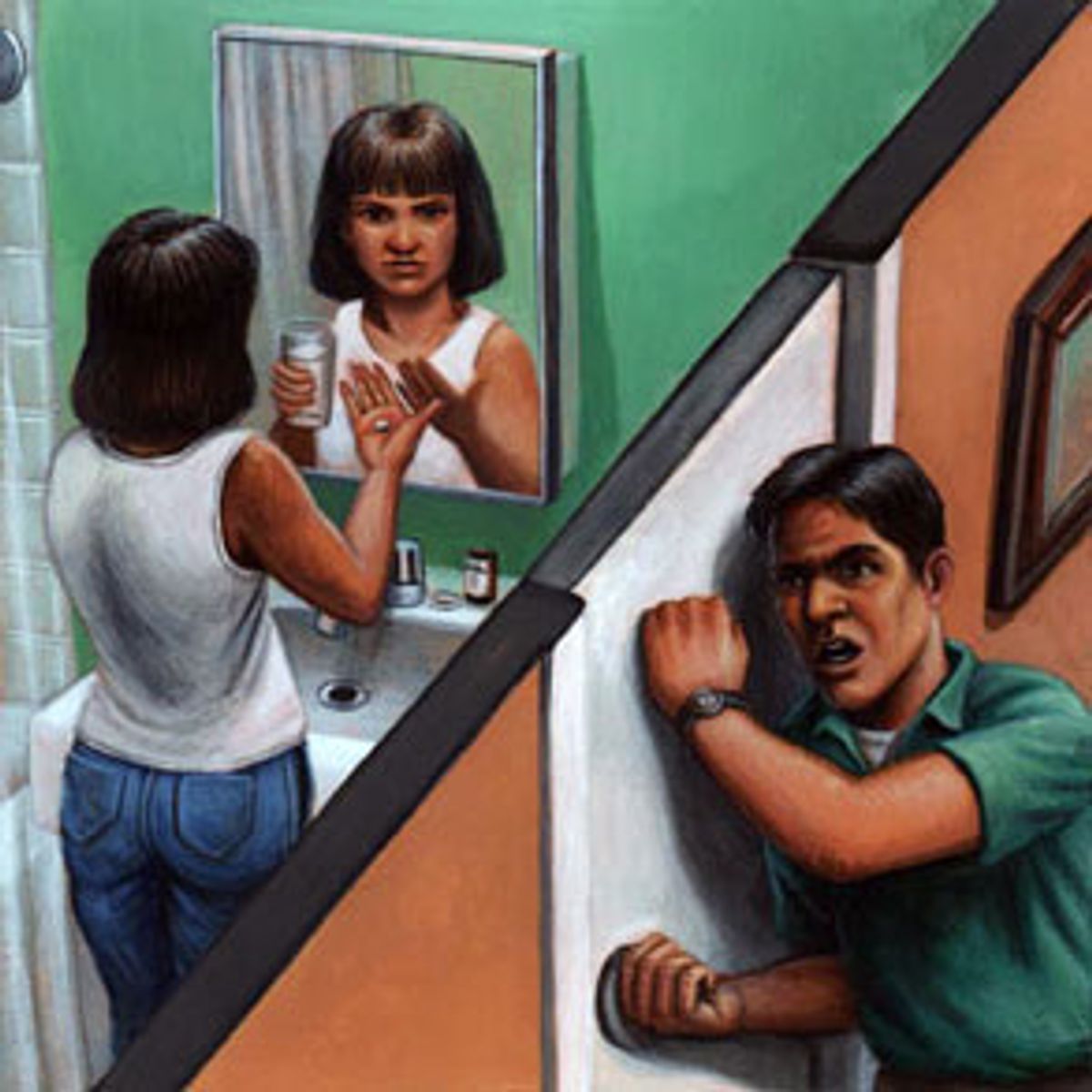

If she does not want to be a mother, a woman can end the pregnancy, with or without her partner's knowledge. (It's hard to tell how RU-486 will affect a woman's ability to exclude the man from her decision; a drug-induced abortion at home may be more private and less invasive than surgery at a clinic, but it's not easy to hide from an intimate partner.)

If she wants to carry her baby to term, a woman can force the father to pay child support -- so, as lawyer Melanie McCulley points out in a 1998 article in the Journal of Law and Policy, he "does not have the luxury, after the fact of conception, to decide that he is not ready for fatherhood." A woman also can have a baby and not tell the father, making a unilateral decision to give the child up for adoption or raise it on her own.

To some extent, this inequality stems from the obvious fact that a woman's body is the vessel for gestation and the vehicle for birth. Once upon a time, biology colluded with cultural and legal male privilege to ensure that women generally paid the price for illicit sex. Scientific progress and the advancement of women changed that. Even as reliable contraception and legal abortion allowed women to control their reproductive fates, their ability to hold absentee fathers financially liable for their children was enhanced by new methods of establishing paternity enforced by friendlier courts.

"In the old days, a woman's biology was a woman's destiny," writes Warren Farrell, author and men's issues advocate, in the forthcoming book "Father and Child Reunion" (to be published in January). "[T]oday, a woman's biology is a man's destiny."

The rhetoric of pro-choice advocates rarely mentions men at all, except to celebrate women's freedom from male control over their reproductive lives. Anti-abortion rhetoric occasionally refers to bereaved fathers of aborted fetuses but more often invokes evil males for whom legal abortion makes it easy to seduce and abandon women, and who may even coerce women into having abortions.

Many men, and some women, see a very different situation -- one in which women have rights and choices while men have responsibilities and are expected to support any choice a woman makes. "If she wants an abortion, he's supposed to shut down all of his emotional bonding to the child," says Fred Hayward, founder of the Sacramento, Calif., group Men's Rights Inc. "Then, if she changes her mind and decides to have the baby, he's supposed to turn it all back on and be a father."

Hayward's opinion is shared by Ron Henry, a Washington attorney (married with three children) who works pro bono promoting shared parenting by divorced and unmarried parents: The expectation that men will "switch" to support the woman's change of heart, Henry says, is "a fundamental denial of men's humanity, as if they just exist to make the woman happy."

Activists aside, where do most men fit into the picture? Tellingly, very few studies have looked at the men implicated in unwanted pregnancies. The only book on the subject, apparently, is the 1984 volume "Men and Abortion: Lessons, Losses, and Love" by Drexel University sociologist Arthur Shostak and journalist Gary McLouth, based on a survey of 1,000 men in abortion-clinic waiting rooms and some in-depth interviews.

Most men in the survey reported that ending the pregnancy was a mutual decision, and only 5 percent didn't want the abortion -- though nearly half of the single and divorced men said that they had suggested getting married and having the baby. As for the roughly 50 percent of men who don't show up at the clinics, various estimates cited by Shostak and McLouth suggest that while some fit the stereotype of the feckless runaway male, a significant percentage oppose the abortion or are too upset about it to come along. As many as one in six men are never told about the pregnancy or the abortion.

Some men who spoke to the Bergen (N.J.) Record a few years ago for an article on men and abortion keenly felt their powerlessness. Bill, a builder, was ecstatic when his fiancée became pregnant. Raised in a broken home, he dreamed of being the caring father he never had. His joy turned to grief when she told him she had miscarried -- and agony when he came across a receipt from an abortion clinic.

"I cried for two hours, then went into my truck and just drove and drove for hours," recalled Bill, who was 25 at the time. "I hadn't even been given a chance to say yes or no to that baby ... OK, she was the one carrying it, but I was never even consulted."

When he confronted his 20-year-old fiancée, she told him she felt too young for motherhood. Somehow, they worked things out; in less than a year, she got pregnant again and assured Bill that she wanted to have the baby. Several weeks later, after a fight about buying a house, she went to stay with a friend for a few days "to clear her head" -- and had an abortion. When her sister called to tell Bill, he screamed with anguish and rage, threw some lamps around and smashed all the framed photos of them together; after cleaning up the mess, he went to a bar and drank himself senseless. His fiancée actually returned, but they soon broke up.

"I couldn't get over the pain," said Bill. "I didn't even date anybody for a year, and I lost all interest in sex. It was a long time before I could trust anyone again." (At the time of the interview eight years later, he was happily married, with a stepson he had adopted and a baby on the way.)

Of course, men's lack of reproductive rights has another side: being forced to assume the burden of unwanted parenthood, at least financially. In the eyes of the law, it seems that virtually no circumstances, however bizarre or outrageous, can mitigate the biological father's liability for child support, as an overview of cases published in Divorce Litigation journal in 1999 shows.

Did the woman ask him to impregnate her and sign an agreement relieving him of any financial obligations? He's still liable if she changes her mind. Was he underage and legally a victim of statutory rape? Makes no difference. (One such case, in Kansas in 1993, involved a 12-year-old boy molested by a baby sitter.) Did the woman have her way with him when he had passed out from drinking and brag to friends that she had saved herself a trip to the sperm bank? Tough luck, said Alabama courts. Did she retrieve his semen from the condom she had asked him to wear during oral sex and inseminate herself with a syringe? Yes, it's a true story, and in 1997 the Louisiana Court of Appeals told the man to pay up, saying that a male who has any sexual contact with a woman -- even oral sex with a condom -- should assume that a pregnancy may ensue.

Even in less dramatic cases that involve sex between two consenting adults with no coercion or deception, there is a fundamental imbalance. A woman who gets pregnant in her freshman year in college can decide that she's not ready to be a mother, or that having a child would disrupt her life too much. A man can find himself in the predicament of "A Dad Too Soon in N.J.," a 27-year-old newlywed graduate student who wrote to Ann Landers that he got a young woman pregnant as a "very naive" 18-year-old and tried in vain to persuade her to have an abortion or put the baby up for adoption. The woman had recently filed for child support, and he was "burned up" about having to make payments he couldn't afford for a child he had never wanted -- a child that, as he saw it, the mother alone decided to bring into the world. (Predictably, Ann's response was that "Dad" should quit whining and meet his obligations.)

Some argue that the law should treat women and men more equally. One proposed measure is "veto for fathers," which is as simple as it sounds: No abortion can be performed without the prospective father's consent. (Proponents of this idea do stipulate that a man who blocks an abortion must be willing to take full responsibility for raising the child.)

The language of the Veto 4 Fathers Web site strongly suggests a general anti-abortion agenda. But the idea is also endorsed by men's and fathers' groups, such as Fathers for Equal Rights and the National Coalition of Free Men (NCFM), which emphasize that their position on the issue of choice is distinct from that of the pro-life movement.

The NCFM's "Declaration of the Father's Fundamental Pre-Natal Rights," adopted in 1992, states that "the prospective father has the fundamental right to participate with his partner-in-conception in any decision affecting the future of the fetus he helped create" and "a fundamental right of custody" equal to the woman's.

A competing proposal, "Choice for Men," leans in favor of the partner who doesn't want to be a parent: It would allow a man to legally "abort" his parental rights and responsibilities within a limited time of being notified of the pregnancy.

"Ending paternity suits against men is the equivalent to legalizing abortion for women," Hayward of Men's Rights Inc., wrote in the Berkeley, Calif., alternative weekly the Spectator in 1992. McCulley's article in the Journal of Law and Policy, provocatively titled "The Male Abortion," endorses this idea and features a model statute under which an unwed father could petition for paternity termination.

So far, neither paternal veto nor male choice has much chance of becoming law. While polls show that at least two-thirds of Americans believe a husband should be notified before his wife has an abortion, and a majority may even favor a father's right to block an abortion, the Supreme Court does not agree. In 1976, the court struck down abortion laws mandating spousal consent; in 1992, in Planned Parenthood vs. Casey, it also nixed spousal notification requirements as an "undue burden" on women seeking abortions.

In the 1980s, some men managed to obtain court injunctions or restraining orders barring their wives, ex-wives or girlfriends from having an abortion, but all these orders were thrown out by appellate courts. (Almost invariably, the women went ahead and had the abortion anyway while the injunction was still in force.)

As for "men's right to choose," the federal judiciary has yet to tackle this issue. Six years ago, the National Center for Men in New York announced its search for a plaintiff for a "Roe vs. Wade for men" lawsuit, an effort that attracted some media attention but ultimately fizzled.

Some men fighting paternity claims in several states have tried to argue, so far without success, that "forced parenthood" denies equal protection for men as long as women have the right to abortion. Peter Wallis, a New Mexico real estate broker, was equally unsuccessful in his suit against his ex-girlfriend, Kellie Smith, in 1998 for "intentionally acquiring and misusing" his bodily fluids by getting pregnant against his wishes; after a flurry of publicity, the case was tossed out. A few family court judges have sided with men who could prove that they were deliberately trapped -- for instance, that the woman lied about using birth control -- but none of those decisions survived on appeal.

If such a case does go to the Supreme Court, the equal protection argument is unlikely to hold up. It doesn't take a brilliant mind to make the case that men and women are not similarly situated with regard to pregnancy and childbearing. Moreover, under prevailing constitutional doctrine, unequal treatment of the sexes, while generally presumed to be illegal, can be justified (unlike race discrimination) by a "compelling state interest" -- such as ensuring adequate support for children already born.

Legal issues aside, do champions of men's reproductive rights have a moral leg to stand on? Are they apologists for male fecklessness or male dominance, backlashers who resent women's new rights, or cutting-edge fighters for equal justice?

The objection to paternal veto is easy to understand: A woman has physical primacy in every case. In surveys and interviews, even men who resent having so little say when it comes to dealing with a pregnancy generally agree that the woman should have the final word. (In Shostak's abortion clinic sample, nearly 60 percent of men agreed that a boyfriend should have input in the abortion decision, and 80 percent felt a husband should have an equal role -- yet, somewhat paradoxically, 60 percent agreed that if a wife wants the abortion, she should have it even over her husband's objections.)

It is not necessarily a sign of anti-male bias, as men's advocates contend, that a man's ability to control his income and his labor isn't accorded the same respect as a woman's ability to control her body. In our culture, bodily autonomy is seen as a more fundamental value than property; that's why chopping off an offender's finger seems to us far more barbaric than stiff financial penalties or even forced labor.

And yet, in a broader sense, men's autonomy is an issue. Advocates of choice for men like to cite a passage from a Planned Parenthood statement, "9 Reasons Why Abortions Are Legal": "At the most basic level, the abortion issue is not really about abortion. ... Should women make their own decisions about family, career and how to live their lives? Or should government do that for them? Do women have the option of deciding when or whether to have children?"

Substitute "men" for "women," and it's hard to deny that coerced fatherhood drastically curtails a man's ability to make key decisions about how to live his life, including when or whether to have children with the woman he loves. Think of "A Dad Too Soon," the young husband saddled with college loans, graduate school tuition, car payments and other expenses, and forced to give up a quarter of his earnings because he made a mistake as a teenager. (His admittedly one-sided narrative also suggests that the mother's paternity suit was partly driven by vindictiveness: Having waited for eight years, she filed the claim days after his wedding.) Yet, in the eyes of Ann Landers and many others, he deserves only a stern rebuke. Pay up and shut up. You play, you pay. It takes two to tango.

Advocates of "choice for men" have a point when they charge that there is a certain hypocrisy in these declarations, now that the link between sex and procreation has ceased to be binding for women. "We are no longer being truthful when we chide the male defendant: 'It took two to make the baby,'" writes Fred Hayward. "It might have taken two to conceive an embryo, but thanks to legalized abortion, only one person controlled whether or not the baby was made."

Some maverick feminists agree with this view. Karen DeCrow, an attorney who served as president of the National Organization for Women from 1974 to 1977, has written that "if a woman makes a unilateral decision to bring pregnancy to term, and the biological father does not, and cannot, share in this decision, he should not be liable for 21 years of support ... autonomous women making independent decisions about their lives should not expect men to finance their choice."

Yet, by and large, feminists and pro-choice activists have not been sympathetic to calls for men's reproductive freedom. "If there is a birth, the man has an obligation to support the child," says Marcia Greenberger, co-president of the National Women's Law Center. "The distinction with respect to abortion is the physical toll that it takes on a woman to carry a fetus to term, which doesn't have any translation for men. Once the child is born, neither can walk away from the obligations of parenthood." (Actually, a woman can give up the child for adoption, often without the father's consent, and be free of any further obligation.)

Indeed, on the issue of choice for men, staunch supporters of abortion rights can sound like an eerie echo of the other side: "They have a choice -- use condoms, get sterilized or keep their pants on." "They should think about the consequences before they have sex." (The irony is not lost on men's choice advocates or pro-lifers.) Yes, some admit, it's unfair that women still have a choice after conception and men don't, but biology isn't fair. As a male friend of mine succinctly put it, "Them's the breaks."

Is all this really about the "best interest of the children"? Single mothers are not required to seek money from the father, unless they apply for government benefits; many never file for child support, often because they don't want the guy in their or the children's lives. What's more, when a single woman exercises her reproductive autonomy by going to a sperm bank, she denies her child any chance of getting a penny from the man who supplied his DNA, and the government won't and can't stop her.

Feminists often argue, correctly no doubt, that many pro-lifers are motivated less by concern for the unborn than by the belief that women who enjoy sex should pay a penalty for it. But maybe even more people today have a similarly punitive attitude toward men. In some comments I have heard, from both men and women, about the danger of "letting men off the hook," the real fear seemed to be not that the children would suffer, but that the men would get off scot-free.

The willingness to liberate women but not men from the unwanted consequences of sex may stem partly from the lingering attitude, conscious or not, that sex is mainly for the man's pleasure. It may also reflect the belief that men are irresponsible and thus more likely to abuse their freedom.

Some day, perhaps in our lifetime, science will add a new wrinkle to these issues. Reproductive technology will have advanced to the point where the fetus can be taken from the womb early in the pregnancy, with no more medical risk than an abortion, and incubated until it becomes viable. Will the law then allow the man to petition for custody of the unborn child if the woman doesn't want it? Will he be able to sue her for child support afterward? Will many feminists argue that it's an intolerable violation of a woman's reproductive freedom that her child should be brought into the world without her consent, let alone that she should be stuck with the bill?

In the meantime, we have to deal with biological realities as they are. Given these realities, it may be nearly impossible to come up with a solution that wouldn't be unfair either to men or to women. The current situation is clearly inequitable to men. But allow a veto for fathers, and it raises the disturbing specter of giving a man authority over a woman's body. Allow choice for men, and some will find it galling that a woman who wants to avoid the burden of parenthood has to undergo surgery or drug treatment with unpleasant side effects while a man merely fills out some forms.

The argument for at least notifying the prospective father of an abortion (with a waiver for cases in which the woman has a reasonable fear of bodily harm from the man, or the pregnancy results from rape), seems compelling. Shostak, co-author of "Men and Abortion," believes that a man should have an opportunity to "plead his case" to a woman if he wants her to have their baby.

There is also a strong case for providing some options for men to terminate their paternity. (At the very least, a woman who never bothered to let the man know that he was a daddy shouldn't be able to hit him up for back pay 10 or 15 years later.)

Of course, "choice for men" could have complications beyond the issue of children's economic welfare; for one, the man could later have a change of heart. While proposals for a "paper abortion" would make the procedure irrevocable, Fred Hayward concedes that "it's a tough one," since sometimes the child could clearly benefit from reestablishing a relationship with the father.

McCulley believes that a quick, early paternity termination would be better for the child than long, traumatic and often ultimately unsuccessful battles to extract money from an unwilling father. More intriguing, some proponents of men's right to choose, such as Jack Kammer, author of the online book "If Men Have All the Power How Come Women Make the Rules," argue that the option of declining fatherhood would make child abandonment less common.

"The notion of fatherhood as a trap, a burden, a yoke is strong in male culture," says Kammer. "By making fatherhood a choice, we will allow it to become an obligation freely taken, not to be resented or avoided."

And that, advocates for men say, is the real point -- not men's ability to control women or to desert children, but the ability to have input in decisions that profoundly affect their lives.

Maybe there is no good answer to the dilemma of male reproductive rights. Still, it is an issue that should prompt us to rethink some deeply held assumptions. It should make us realize that, if men who want a right to be released from their parental obligations seem callously egocentric to many people, that's how women who want abortion on demand look to many anti-abortion advocates. It should make us ponder the fact that, while paternal desertion is often cited as evidence of male irresponsibility and selfishness, more than a million American women every year walk away from the burdens of motherhood.

Above all, perhaps, the issue of men's reproductive autonomy brings home the fact that abortion can create a radical imbalance rather than equality between the sexes. For years, women have been sending a mixed message to men: Sometimes we expect them to be full partners in child-rearing, sometimes we treat them as little more than sperm donors, walking cash machines or bystanders. If men's parental role is to be taken seriously, women need to assume a moral, if not legal, obligation to involve their partners in any decision about pregnancy and we all need to have a serious conversation about men's reproductive rights -- no matter where that conversation may lead.

Shares