Over the past year, syndicated columnist Lenore Skenazy, 49, has become something of a heretic. She's an American mother of two boys, now 11 and 13, who dares to suggest that today's kids aren't growing up in constant state of near peril.

Amid the cacophony of terrifying Amber Alerts and safety tips for every holiday, Skenazy is a chipper alternative, arguing that raising children in the United States now isn't more dangerous than it was when today's generation of parents were young. And back then, it was reasonably safe, too. So why does shooing the kids outside and telling them to have fun and be home by dark seem irresponsible to so many middle-class parents today?

Skenazy first instigated a kerfuffle about contemporary parenting mores when she and her husband allowed their then 9-year-old son Izzy to ride the subway alone in April 2008. After she wrote a column about Izzy's independent excursion, she and the little subway veteran made the rounds on TV morning shows and cable news, where Skenazy fielded heated questions about her common sense, if not her outright sanity. The tsk-tsking wasn't limited to the TV talking heads, either. This year, a train conductor on the Long Island Rail Road called the police after then 10-year-old Izzy took a train ride by himself. (For the record, it's entirely legal.)

In her new book, "Free-Range Kids: Giving Our Children the Freedom We Had Without Going Nuts With Worry," Skenazy suggests that many American parents are in the grips of a national hysteria about child safety, which is fed by sensationalistic media coverage of child abductions, safety tips from alarmist parenting mags, and companies marketing products that promise to protect tykes from every possible danger. She by no means recommends that mom and dad chuck the car seats, but says that trying to fend off every possible risk, however remote, holds its own unfortunate, unintended consequences.

Salon spoke with Skenazy from her apartment in Manhattan, where she lives with her husband and sons.

I grew up in the Houston suburbs in the '70s and '80s. Back then, we kids waited for the school bus without our parents. Now, in that exact same neighborhood, parents always wait at the school bus stop with their kids, although the neighborhood has not changed significantly.

This was a shock to me. Now, parents wait at the bus stop. They wait in the morning to make sure their kid gets on safely, and sometimes they wait at the bus stop in the afternoon to drive the kid home, even if it's on the same block, even if it's in a gated community. Sometimes they wait with those little golf carts. It's the new social norm.

What do you think are the reasons that change has taken place?

When I was growing up, my parents were not watching those horrific television shows that are on now like "CSI" and "Law & Order: Special Victims Unit." They were watching "Dallas," "Dynasty," stuff with maybe big hair, but that was the biggest crime. It wasn't all these shows with really graphic, horrifying consequences for kids.

And then, you didn't have cable, and cable has to fill 24 hours with the worst possible stories, because if they filled it with stories about kids getting home safely, you wouldn't watch. What's the most compelling story that anyone has come up with so far? It's something terrible happening to a child.

Just today before our conversation, I looked at the CNN.com homepage, and there was a story about a 17-year-old disappearing while on spring break, and then another story about a teen vanishing after arguing with a teacher.

And if there isn't some teen disappearing just today, they'll say: "Cold case! Remember when?" And then they'll go back a few years, "So-and-so still not found." So, these incidents seem like they're happening every second of every day. News crews have no compunction about spending months hanging out in Aruba or Portugal when there is a case of a young white girl stolen, and they'll beat that story to death.

It's not like I don't feel tremendous sympathy for the families and for the victims, but it makes it seem like we are living in a world where children are in constant, utter peril, and the statistics actually don't prove that.

What are the statistics about crimes against children? What is the news that we're not hearing?

The crime rate today is equal to what it was back in 1970. In the '70s and '80s, crime was climbing. It peaked around 1993, and since then it's been going down.

If you were a child in the '70s or the '80s and were allowed to go visit your friend down the block, or ride your bike to the library, or play in the park without your parents accompanying you, your children are no less safe than you were.

But it feels so completely different, and we're told that it's completely different, and frankly, when I tell people that it's the same, nobody believes me. We're living in really safe times, and it's hard to believe.

But if crimes against kids have fallen, now that we're keeping them cloistered, won't some people think, "Great! It must be working!"?

Crime stats are falling across the board. It's not just because children are inside, because [crime stats] are falling inside, too. Crimes against children, even by family members and acquaintances, are falling, according to the Crimes Against Children Research Center.

We don't tolerate sex crimes. There's just much less tolerance of any kind of abuse of kids. Those people are prosecuted very aggressively, to the point where a lot of them are behind bars now.

But if other parents aren't letting their kids walk to school, or wait at the bus stop by themselves, if you buck the trend, doesn't that make your kid more vulnerable, because other kids aren't doing it, too? If everyone was doing it, wouldn't there be safety in numbers?

There would be safety in numbers, and I wish everybody would do it. My big idea is: "Take Our Children to the Park and Leave Them There Day." I think that would be a great thing for our country.

Maybe the 7-year-old will walk the 5-year-old home, and nobody would say: "Oh my God, where are the parents? Let's arrest them." Perhaps your child is in .00007 percent more danger, but the danger is so minute to begin with. There is a 1 in 1.5 million chance that your kid would be abducted and killed by a stranger. It is hard to wrap your mind around those numbers, and everybody always assumes: What if it's my 1 in 1.5 million?

If you don't want to have your child in any kind of danger, you really can't do anything. You certainly couldn't drive them in a car, because that's the No. 1 way kids die, as passengers in car accidents.

Rationally, why aren't cars the bogeyman instead of stranger abduction?

It would change our entire lifestyle if we couldn't drive our kids in a car, and it's a danger that we just willingly accept without examining it too much, because we know that the chances are very slim that we're going to have a fatal car accident. But the chances are 40 times slimmer that your kid walking to school, whether or not she's the only one, is going to be hurt by a stranger.

Isn't it ironic that parents are driving around their kids to protect them, but riding in a car is the greater danger?

Oh, it's all ironic!

But when you see something graphic and horrifying, it doesn't go to the back of your mind under "very unlikely scenario," it goes to the front of your mind, as, like, Oh my God.

And when I say: "Walk to school," you're thinking, What about that girl in the trailer park in California who was walking to her friend's house the other day? [Sandra Cantu, 8, of Tracy, was murdered in late March 2009. The chief suspect is the child's Sunday school teacher, who is also the mother of one of the girl's friends.] That's the image you have. You get despairing and worried, and then you remember afterward there was probably some expert on TV saying: "Parents, here are some tips for you."

As if there is a tip that can tell you, "Remember parents: Don't ever let your child out of the house to go visit a playmate." That's what the tip would be, and it wouldn't make any sense. Preparing for such unlikely scenarios is like preparing for, "Remember parents: Asteroids happen, so keep your children inside!"

But we are bombarded with advice like that all the time, not only from TV, but from the parenting magazines. If you start reading them, they will drive you crazy, too. They make everything into a potential for disaster. There was one article on kite flying with kids: "Choose a sunny day when there is no chance of lightning." It's like, oh, thanks, because I was really thinking, Should I go out when the thunder is rumbling, and when it's already lashing rain, and you see a witch flying by on a broomstick? Everything becomes the worst-possible-case scenario and almost laughably terrible.

Then there are products out there that will prevent this from happening. Here is a helmet your child could wear when she starts to toddle, lest she fall over and split her head open and die, or suffer traumatic brain injury.

Kids have been toddling -- it's a whole stage we actually call toddlerhood -- ever since we started walking upright, which has been a pretty successful experiment for the human species. But now you're supposed to think that it's too dangerous for a kid to do without extra protection and without extra supervision and without this stupid thing you can buy.

There are kneepads that you're supposed to put on your kid because crawling is considered too dangerous for the knees, as if knees weren't built for crawling. That's why they're cute and dimpled and fat.

Everything that we do has a product that we can buy that's supposed to make our kids safer, as if they're born without the requisite accoutrements. Then there is something we can do as parents to be more careful, to be more protective. The assumption behind all of that is that if you are a good parent, you should be protecting your child from 100 percent of anything that could possibly go wrong, and if not, you will be blamed and Larry King will shake his finger at you.

So children are actually safer, but you're saying parents are more worried?

Parents are more worried because of this stew that we're in. You turn on the TV, and then you look at the magazine, and the magazine says: "How to baby-proof your home," as if your home is filled with rotating knives and lepers and just all sorts of dangers.

But isn't there also a sense in which you feel like you're a good parent because you're worrying? As if all the worrying you do is a sign of how concerned you are about your kids, and how much you love them?

That was the whole backlash against me when I let my kid take the subway at age 9 last year: "Don't you care?" To care is to conjure up the worst possible thing that could happen to them and prepare for it.

There is just no way to protect your kids 100 percent, but we do live in safe nice times when your kids are pretty well protected just by living in America, and just by having a low infant mortality rate, and just by having a pretty safe food supply.

We don't appreciate how great these times are in terms of parents really not having to worry about their kids' safety. Abe Lincoln had four kids. One made it to adulthood. Even when I was born, the infant mortality rate was four times greater than it is now. These are very good times to be a kid, especially in America, and yet we're treating it as if we're growing up in the plague years or downtown Baghdad, or some horrible combination of them both.

You found that a number of other English-speaking countries, like Australia and England, share this American obsession with child safety.

In England, if you want to have anything to do with kids, from being a scout leader to being the class mom who brings in the cupcakes for your school, you have to undergo a police check that promises with an authoritative stamp that you have never been convicted of pedophilia. So every adult there who has any interest in children is assumed to have an interest that's very prurient -- perverse until proven otherwise.

What countries don't share this extreme sense of fear around children?

A lot of other countries really don't understand us. In Japan, kids walk to school at age 5. In Switzerland, they're taking the buses at age 5 and 10. Everybody in pretty much the rest of the world starts walking to school when they start going to school.

In countries where there's a need for more hands on deck to harvest the grain or the coffee or the corn, kids start doing that as soon as they're able. The idea is not to keep them as young and helpless as they can be forever. The idea is to have them become part of the productive society, as opposed to being shuttled everywhere and then: "Wait, honey, I'll open the car door for you."

Wouldn't even children in the United States, historically, have had much more responsibility at young ages?

Ben Franklin was apprenticed to his brother at age 12. Mark Twain was an apprentice, too, and Herman Melville was going off to be captured by cannibals by the time he was 16.

Twelve was sort of the age of maturity. Up until then, it wasn't as if they weren't doing anything. They'd be helping out their fathers. Girls would be pulling sacks of laundry around, or taking care of the younger children. Even today in most societies that don't have a ton of money and do have a ton of children, it's not the mother who's responsible for playing patty-cake with the kid all day long lest the kid not develop his verbal skills and, you know, good eye contact.

The 7-year-old would be taking care of the 5-year-old, and oftentimes the 5-year-old would be taking care of the 3-year-old. Children are more competent than we believe. We forget what kids are capable of. It's interesting, if you look at history, or if you look at other countries, to realize how very specific to 2009 our worries are and the way we think of kids is.

You even compare the situation of American children now to the situation of American women in the 1950s as described in Betty Friedan's "The Feminine Mystique." What do you mean by that?

In the '40s, we had all these women going out like Rosie the Riveter and working in the factories and making the bombers that won the war.

But then in the '50s they were told: "That's crazy! It's too dangerous out there for you, you fluffy little endangered vulnerable sweetheart that I love so much that I'm smothering you into this house, and you have a washing machine, and you better be happy there, and I bet you are!"

How is it that this previously totally competent group of people was suddenly told they were too vulnerable and too soft and too sweet to go out there in the outside world? Then along came feminism, and we said: "Yeah, that was a mass delusion. OK, that was weird."

Recently, the same thing that happened to women in the '50s has happened to children. They're being told: "Oh wait, you're not safe enough out there. That world is too big for you." Instead of being told it's a male world, we're being told it's a grown-up, evil world.

Once again a whole group of previously competent individuals, in this case children, are suddenly being told they are not safe in the outside world, and they couldn't possibly figure out how to deal with it, or make their way through it, and they need to be home.

What message do you think that sends to the kids themselves? That they're incompetent?

Not only that they're incompetent. It says to them that they're in danger.

You want kids to feel like the world isn't so dangerous. You want to teach them how to cross the street safely. You want to teach them that you never go off with a stranger. You teach them what to do in an emergency, and then you assume that generally emergencies don't happen, but they're prepared if they do. Then, you let them go out.

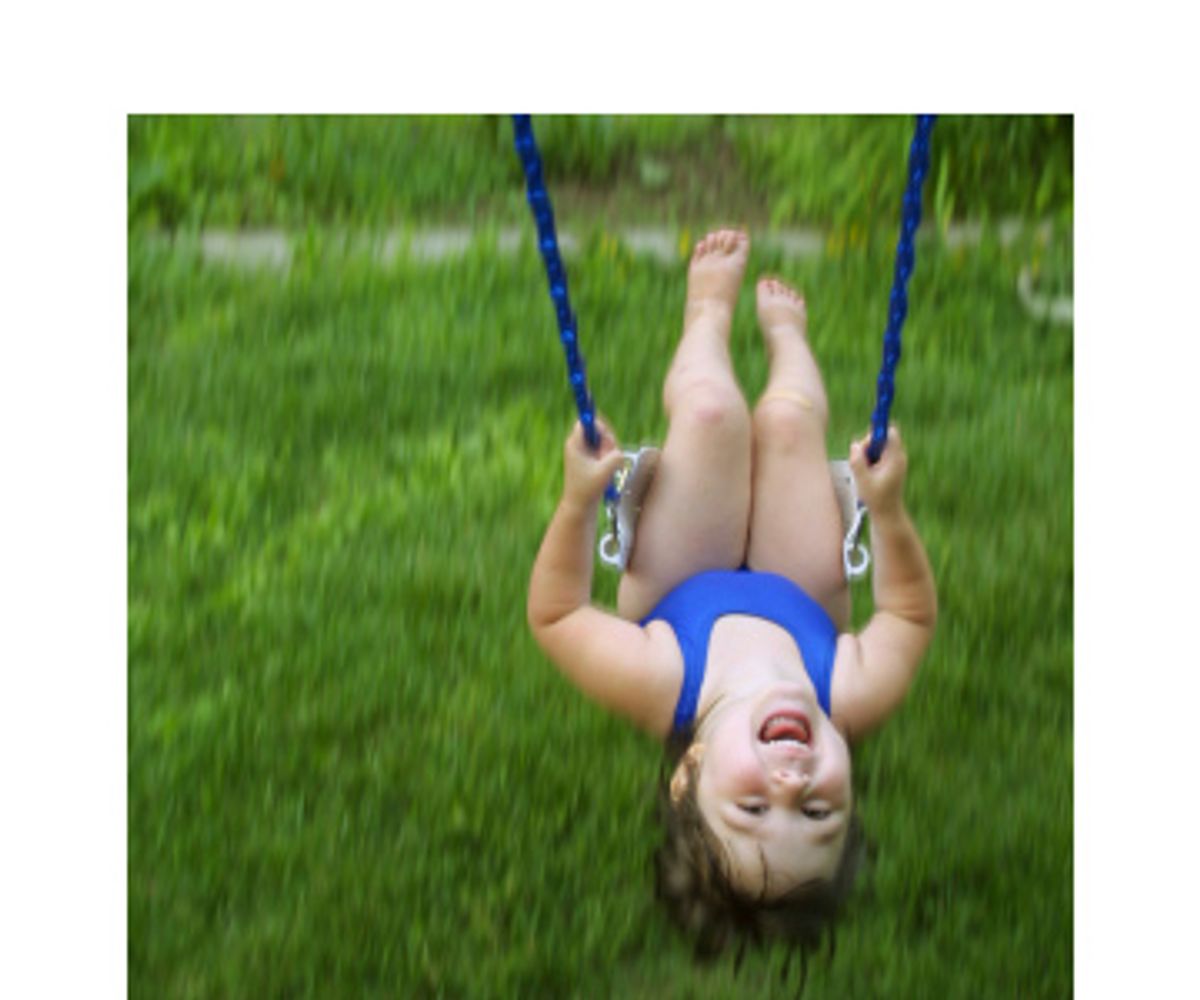

The fun of childhood is not holding your mom's hand. The fun of childhood is when you don't have to hold your mom's hand, when you've done something that you can feel proud of. To take all those possibilities away from our kids seems like saying: "I'm giving you the greatest gift of all, I'm giving you safety. Oh, and by the way I'm taking away your childhood and any sense of self-confidence or pride. I hope you don't mind."

What's your take on Internet sexual predators?

The world online turns out to be not very different from the world offline. There are some really seedy neighborhoods where you wouldn't want your kids hanging out, especially if they were wearing high-heeled shoes and fishnets stockings at night. If your kids don't go there, then your kids are not going to be stalked by predators just looking up prom pictures on Facebook.

David Finkelhor, the head of the Crimes Against Children Research Center, has discovered pedophiles don't want to waste their time just flipping through MySpace pages or Facebook pages. It's as futile as trying to call up random numbers from the phonebook and trying to get a date. It's just a waste of time.

They would rather go for the low-hanging fruit: young people hanging out in sexually suggestive chat rooms presenting themselves in a sexual way -- "Oh, I wonder what that's like" or, "If only somebody would buy me an iPod and a lollipop, I would be a very happy girl or boy."

If your kid is just texting his friends, or posting pictures on Facebook or AIM'ing, it's no more dangerous than them talking to each other as they walk down the sidewalk, or at the mall.

What's a simple way for parents to give their kids a somewhat freer rein?

Don't take your cellphone with you for a day. What does that mean? That means that your child can't be like mine, who called me when I was just down the hall, getting in the elevator, to ask: "Mom, can I have another piece of banana bread for breakfast?"

I was so sad for me, having brought up such a perfect boy that he thinks he has to ask this, and sad for him, thinking that he couldn't make his own mind up. With a cellphone, parents are tethered to their kids as closely as when kids are toddlers, and you're actually watching every step because you have to be there, 'cause you don't want them to drink the bleach.

As a parent, is it really possible to train yourself not to fixate on the worst-case scenarios?

It's not like I'm immune to "what if" and worry. But we've started to think of our kids as the most vulnerable, the most endangered, the least competent, the most, uh, dumb generation in history that needs the most supervision the most hours of the day, literally, than anybody until now.

And when you get a little perspective, you can take these little baby steps and say: "OK, maybe I can let my 9-year-old trick-or-treat [by himself]. After all, at this age if he were living in the Philippines, he'd be running his own vegetable stand, or he'd be riding on the back of a moped with three other kids and a chicken trying to go get dinner for mom."

I also think about what we do give our kids when we give them the chance to do something themselves: to get themselves out of boredom, to get themselves to school, to become competent and to become worldly, and actually be safer in the long run.

Shares