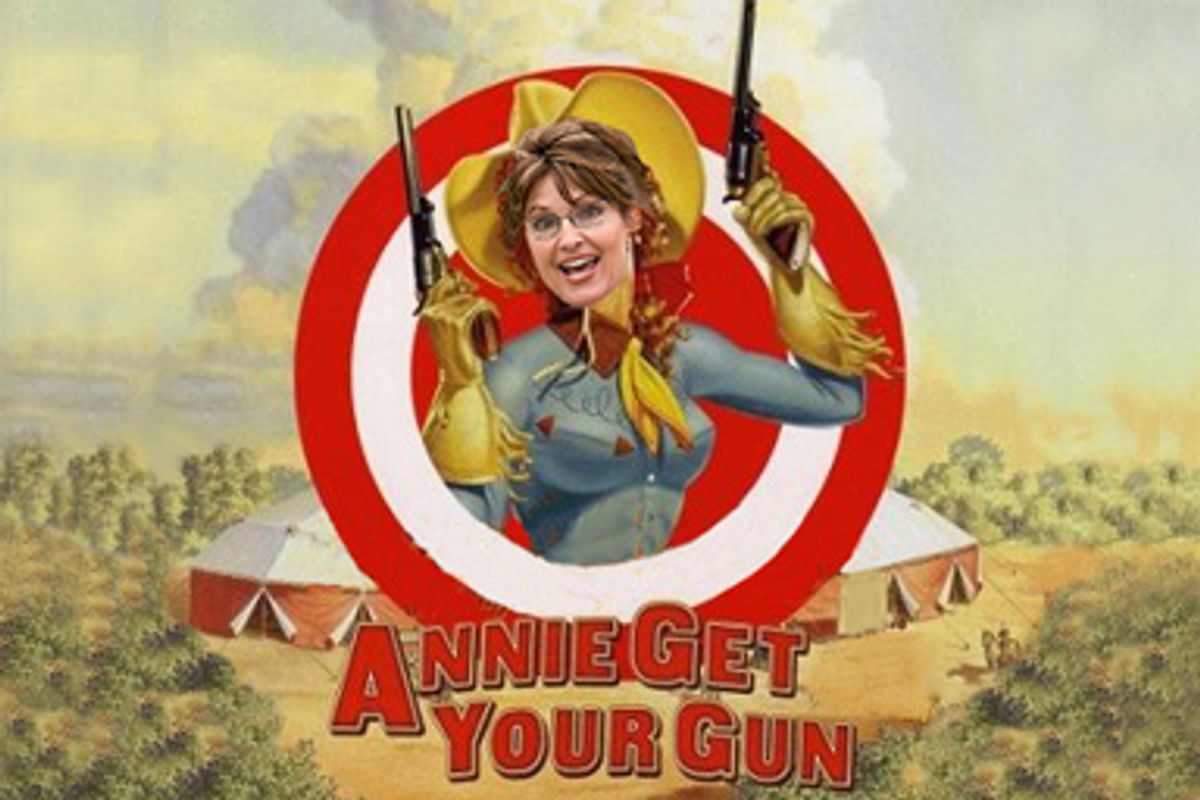

Sarah Palin’s ascent, not unlike Barack Obama’s, is an American story. The hockey mom becomes the mayor who becomes the governor who becomes the national candidate. She’s a folkloric character: Annie Oakley, Horatio Alger and Gatsby in one. Even her florid self-mythologizing is an accepted cultural tradition. She is the girl from the sticks who made it big. She is a pragmatic, can-do feminist who’s convinced, as she told Oprah, that an American woman can have it all but that “some things might have to be put on the back burner.” Say what you want about Palin or her positions (and, in the past, I have), it takes scrappiness and guts to strike back at the old-boys' network that anointed you by publishing a book, so soon after the campaign, detailing your frustrations and disillusionments. We might want to take a long breath before discounting her. As Gwen Ifill recently said on "This Week": “You can not underestimate the degree that women will be drawn to her story.” We don’t hear many real-life fairy-tales of American female success, which makes the few that exist intrinsically compelling.

But Sarah Palin’s story is also peculiarly modern and culturally apt in another, more unsettling way. As the vice-presidential candidate, she showed, despite her postgame spin, little real knowledge of matters non-Alaskan, and at least for the span of the campaign, she didn’t seem bent on acquiring much more. Her current desire for visibility, the motives for which remain unclear, suits our age of reality television, this moment in American life when fame for fame’s sake is the ultimate goal. One might argue that Palin’s ambition, which some have branded simple narcissism, allowed her to forget her own unreadiness for the presidency and accept the nomination in the first place.

Yet in her interviews the past two days with Oprah and Barbara Walters, Palin seemed wiser and more seasoned than she was just one year ago. It wasn’t only that she looked older, the creases around her mouth having deepened, it was also that, no longer under the shadow of McCain and his handlers, she came off as natural, confident, good-humored and even, at times, articulate. Though her tendency to ramble persisted, she wasn’t as awkward and garbled as in the past. She was also disarmingly honest. “It was easy to understand why a woman would feel that it's easier to just do away with some less-than-ideal circumstances, to do away with the problem,” she told Oprah, about the soul-searching she underwent on learning that Trig would be born with Down syndrome. And about that fateful interview with Katie Couric, she noted, "Of course, I’m thinking, 'If you thought that was a good interview, I don’t know what a bad interview was.’” Watching her — though I may be nearly alone here — it was almost possible to buy the narrative that McCain’s advisors, in their contempt for her, genuinely threw her off her game and then, by silencing her, conveyed the sense she shouldn’t have tried to play at all. Or at least it was possible to understand why many Palin supporters believe this. It even seemed plausible that her risible cocktail of big words and folk sayings was an attempt to ape political rhetoric that she wasn’t trained in and found intimidating. Maybe, in an earnest, rushed attempt to jam together a highfalutin idiom, to sound like the politicians on TV rather than the one she happened to be, she scrambled her own persona.

After all, as the populist governor of a state whose voters respond to plainspoken directness, she suddenly found herself a national figure addressing big-media sophisticates. She was given about seven seconds to learn her role and then, after eight seconds, patronized and mocked. The reasons she performed so poorly are the very reasons her fan base loves her. If, over the next three years, her performance improves as much as it appears to have in just the last year, the conventional rap about her rustic idiocy may come off as mean-spirited and archaic. Her foes might be wise to contemplate the notion that someone of Palin’s background and sensibilities has a right, regardless of her views, to participate in the national debate merely because she speaks (though often unclearly) for many like her. If this possibility can’t be countenanced, then government for the people by the people is an abstract idea we’ve grown too cynical to practice. Sarah Palin endures not because she’s brilliant, smooth or philosophically correct, but because hope in democracy endures, too.

Shares