I've always considered Opening Day of the baseball season to be the real first day of spring. Baseball is the first event of the year in the Northeast that must take place outdoors. Don't worry, I'm not going to go all George Will on you. It is the one day when all the teams start out even, regardless of payroll, and everyone feels hope for the new season (unless you're a Kansas City Royals fan). Even this die-hard Mets fan experiences optimism, though I know that by August I will feel like Charlie Brown to the season's Lucy holding a football.

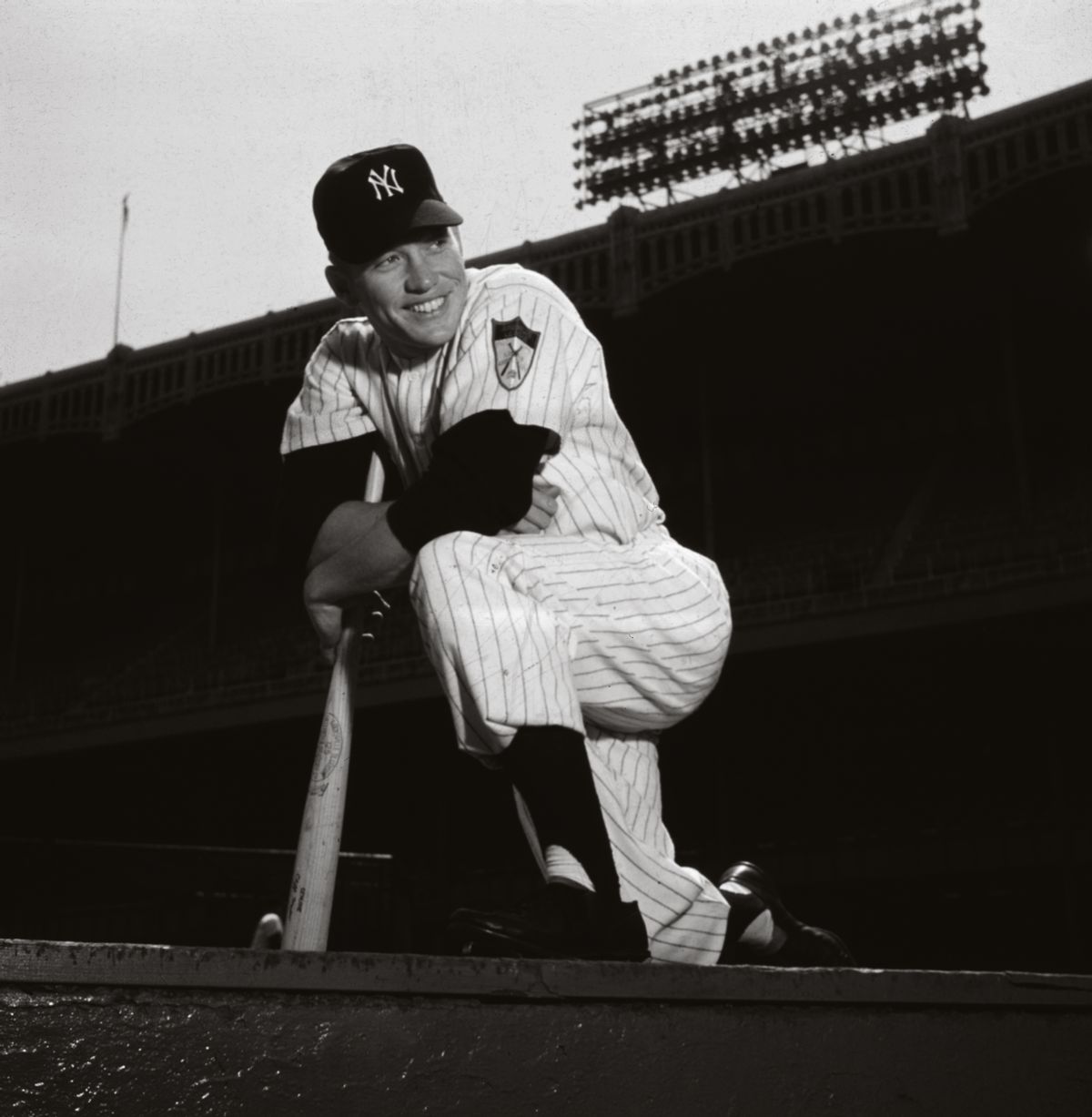

On Opening Day, I will remember Aug. 10, 1958, the first time I stepped inside a major league stadium to see the Yankees host the Red Sox in a Sunday doubleheader. No, I don't have a photographic memory; I have a box score retrieved through a Web site. After all, I don't remember either of Mickey Mantle's doubles, or any of Yogi Berra's five at-bats or Ted Williams' two-run pinch-hit single.

What I remember as clear as if it were yesterday is walking up the mezzanine ramp, a 7-year-old who had only seen games on a black-and-white television, and being stunned at the sight of Yankee Stadium field in all its colorful glory. The outfield was the lushest green I'd ever seen; the infield dirt was a rich reddish clay; the walls were a sharp black and white, and the facade overhanging the right-field upper deck was majestic. Only my first glimpse of the Grand Canyon left a greater impact.

I also have a box score for Friday night, Sept. 1, 1961, when the Detroit Tigers came to the Bronx to challenge one of the most powerful Yankee teams ever. One of over 65,000 who attended that night, I sat in the lower right-field stands, mere feet behind Roger Maris, who was closing in on the home-run record. I cheered when the Yankees scratched out a run in the ninth inning to squeeze out a 1-0 victory over Detroit's Don Mossi (one of the ugliest men to ever don a baseball cap. Sorry, Mossi family).

What I remember as clear as if it were yesterday is walking out on the right-field warning track after the game to exit through the Yankee bullpen. My 10-year-old self was thrilled at standing where Maris had just stood a few minutes earlier and walking near the very bullpen mound where Whitey Ford had warmed up two hours earlier. It felt magical to walk where the gods had walked.

Over time, I switched allegiance to the crosstown Mets. I was sitting in the first row of the upper deck behind home plate at Shea on a chilly night in 1981 when Fernandomania made its first tour of New York. I watched the Dodger phenom Fernando Valenzuela pitch out of a first-inning jam to hurl a complete game shutout. By then, I was old enough to wash down my obligatory hot dog with a beer (or two, or three).

The Mets were abysmal then, but five years later, they were a powerhouse. In October 1986, I was sitting down the right field line for Game 3 of the League Championship when a pre-steroidal, pre-financial guru/bankruptcy filer Lenny "Nails" Dykstra smacked a ninth inning home run into the Mets bullpen for a crucial come-from-behind win as they marched toward their second (and, alas, last) World Championship. It seemed like it took an hour before we stopped cheering and headed to the parking lot.

One of my most vivid baseball memories is immortalized in the song "The Yankee Flipper" by rock supergroup the Baseball Project, which recounts an incident I witnessed at Yankee Stadium on July 18, 1995.

My Yankee fandom had ended years before, but I had won tickets for this game in a trivia contest. I was sitting in the mezzanine behind third base with my kids when Yankee pitcher Jack McDowell exited to an early shower after an abysmal performance and responded to fans' resounding boos by flipping the Stadium crowd the bird.

I still have the back page of the next day's New York Daily News, showing McDowell and his errant digit, under the headline "JACK ASS." The picture doesn't tell the whole story. McDowell imbued his "eff you" gesture with extra emphasis by adding a violent, spinning, upward thrust that, if performed by a proctologist, would have sent his patient screaming toward the emergency room.

According to the Baseball Project song, McDowell, an indie rocker in his spare time, had spent the night before partying with musicians who were in town. Let's just say a few "relief pitchers" were served. I don't know if the story is true, but baseball history is filled with dubious stories, and "caused by a hangover" rings true as an excuse.

But the person I will always remember most on Opening Day is my dad. It was his love of baseball that I inherited. I can still see him playing catch with me as a child, wearing a tattered, old, flat glove that looked like it had been worn by Ty Cobb.

Sports were our bond, even when I became a long-haired hippie. In the fall, I'd save my dirty laundry for Sundays, so I could wash them while watching the NFL games with him. On winter Saturday nights when I was dateless -- meaning most of them -- I'd grab a pizza and bring it over to watch the New York Rangers hockey games on WOR 9 with him. And when the Rangers finally won their elusive Stanley Cup in 1994, there was nowhere I was going to watch the games except on the couch in my father's living room (much to my wife and kids' chagrin).

I remember the evening when my dad got pressed into emergency duty as the umpire in my youth baseball game. I was 10 or 11. My Victoria Theater team was whipping the long-forgotten opponent that didn't seem to have a single decent pitcher; I walked three of my first four times in front of the plate. In my fifth and final at-bat, I half-expected to draw another walk. The 3-2 pitch came in, a full foot outside, and I prepared to drop the bat and head down to first base. "Strike three!" yelled my dad.

I stared at him in disbelief. My own father had called me out with a blatantly bad call! I turned to my coach, who demanded laps from his players when they took a called third strike. In his bewilderment, he excused me from my punishment.

In the car ride home, I asked my father why he'd called me out.

"The pitch was a foot outside," I whined.

"You weren't trying to swing the bat," he explained. "You were being too passive, looking for a walk. I want you to swing the bat and try to get hits."

I pouted all the way home, but I must have eventually absorbed his lesson. Ten years ago, my wife repeated that story at his funeral.

My father's last few years were bad, a jumble of cancer, depression and addiction to painkillers. His behavior was so ornery and unpleasant that my hard-of-hearing mother refused to get a hearing aid until she knew she wouldn't have to hear his complaining anymore. When he finally passed away, frankly, it was a relief to all of us.

But on Opening Day, I wish he was still here.

Play ball!

Shares