Three months ago, in a galaxy far, far away, a couple who'd had trouble conceiving a child finally succeeded, and announced the impending arrival of twins with a cleverly edited and utterly harmless YouTube video that turned the final attack on the Death Star in "Star Wars, Episode IV" into a cheesy metaphor for conception. ("Torpedoes away!") Most of the comments were of the expected variety: generic congratulations and cornball "Star Wars" jokes.

Then there were the others.

"'Thanks for the fuck, should do it again sometime,' should be the ending to this dumb video," wrote one commenter. "Holy fuck was this gay," wrote another. "This is fucking stupid," wrote another. "OH YOU ARE HAVING BABIES? YOU MEAN YOU ARE DOING SOMETHING THAT BILLIONS OF PEOPLE HAVE DONE THROUGHOUT HISTORY? Big fucking deal. I fucking hate kids."

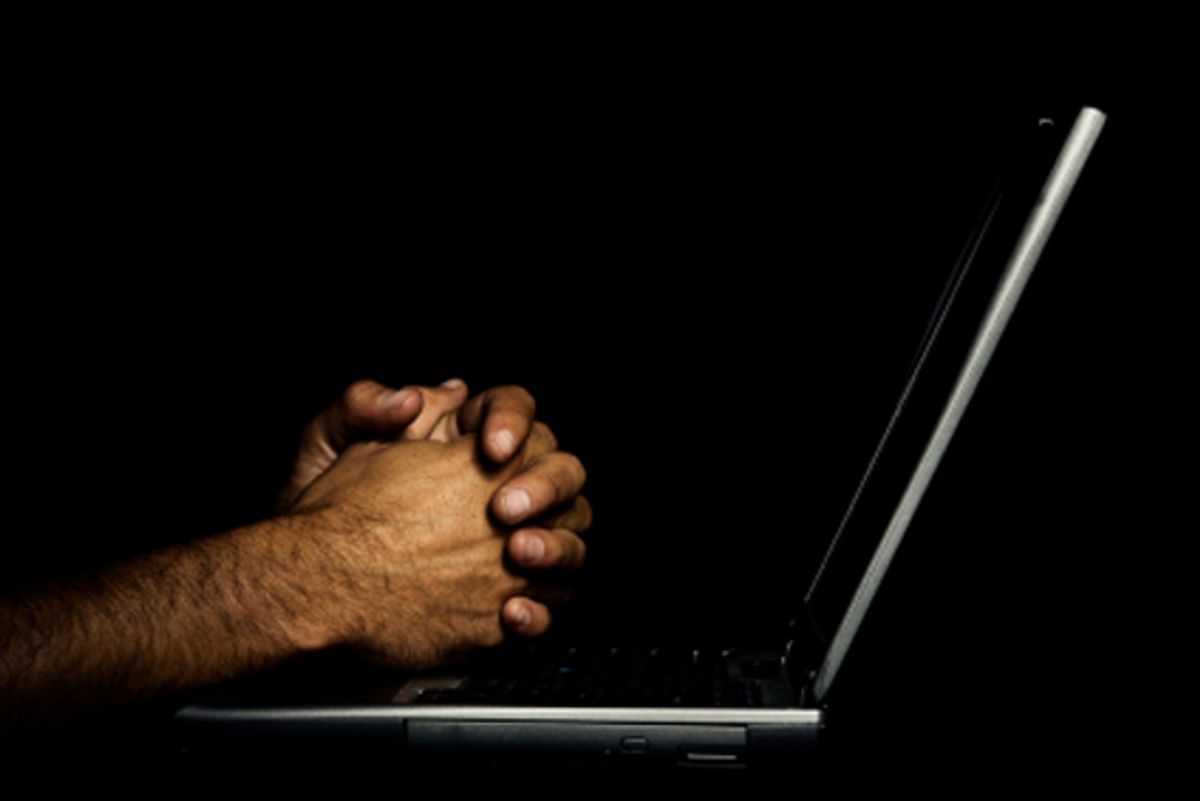

The protective force field of anonymity -- or pseudonymity -- brings out the worst in some people. They say things they would never say in the presence of flesh-and-blood human beings. You see this phenomenon all over the Internet, including Salon, which, despite having some of the smartest and most articulate commenters on the Web, has also attracted its fair share of vitriol. And it's not just in articles about lightning-rod public figures such as Barack Obama or Rush Limbaugh, whom you would expect to inspire heated, sometimes obscene or hateful comments, but in the comments threads of online material that is, in the great scheme, inconsequential, as deserving of bile, profanity and wanton viciousness as a smiley-face button or a paper flower. "It amazes me how easy it is to sit behind a computer and launch a heap of self-righteous cynicism at something as harmless as this," said one commenter in the "Star Wars" birth announcement thread. "Get over your smarmy selves."

Easier said than done.

Some media outlets have decided they've had enough of the endless juvenile trolling and hate-mongering, and have either adopted a stricter moderation policy (such as Politics Daily's calling for a "civilogue") or forced would-be commenters to fill out forms supplying information that would make it easier to track their identities and ban them if they run afoul of the site's rules. The Attleboro (Mass.) Sun-Chronicle recently began asking for commenters' names and charging 99 cents for the privilege. (Salon requires users to create an account before posting, routinely deletes offensive letters and encourages letter writers to flag them themselves.)

Whatever the policy, the intention is always the same: to make it possible for substantive discussion to occur in comments threads, unimpeded by a constant flow of illiterate and often mindlessly provocative brain farts, many of them TYPED IN CAPITAL LETTERS and punctuated with childish ad hominem attacks. The logic behind this cleanup effort is basic, its animating truth self-evident: If a person's real name and/or ISP address were emblazoned across the top of every comment he or she left, the Internet would become more sane, wise and decent overnight.

But for all the downsides of comments-thread anonymity, there's a major upside: It shows us the American id in all its snaggletoothed, pustulent glory, with a transparency that didn't exist before the Internet. And in its rather twisted way, that's a public service.

There's a reason old media outlets were called "the Gatekeepers." Once upon a time, back in a soon-to-be-vanished era when publications were printed on paper that was manufactured from things called trees, if you wanted to send an irate letter to the editor of a publication, you had to take the trouble to write your thoughts on paper, fold the paper, stick it in an envelope, stamp it and put the envelope in a mailbox. This process was itself a kind of filter. Each step gave the writer another reason to think about the subject matter and wording of the letter, and whether or not he actually wanted to send it. Most publications wouldn’t print letters without a verifiable phone number and address ("Hi, this is Janine from the Small Town Times. Am I speaking with Heywood Jablomy?"), and they tended to round-file anything with profanity, ad hominem attacks or language that suggested the letter writer owned an entire collection of tinfoil hats. What ended up on the "Letters to the Editor" page didn't represent the full spectrum of reader response, just the part that wasn't hateful, crazy or indulging a sad fantasy of being John Bender from "The Breakfast Club."

Now you push a button and the comment appears online, unless there's moderation, but many of the larger sites don't bother with moderation because reviewing comments takes time, and time is money.

There are few filters online. That means that just about anything that gets typed into the little "comments" box gets posted. In addition to comments directly addressing the topic of a piece, you may also see tangential rants about whatever group the commenter happens to be obsessed with: women, men, blacks, whites, Jews, Muslims, born-again Christians, Mormons, pagans, short people, Scientologists, movie actors, rappers, guys who wear loafers with black socks. And you'll see the usual suspects riding their pet hobbyhorses through every comments thread on the site: Democrats/Republicans are scum, Bush/Clinton is responsible for the mess we're in, Obama is a racist Muslim foreigner, 9/11 was an inside job. (Of course, the motivation behind many of these rants may also be to get a rise out of other commenters -- a self-perpetuating cycle.)

Whenever a website publicly debates whether to keep allowing anonymous comments or start aggressively moderating (or instituting a more elaborate sign-in process), people in the comments thread beneath the announcement rail against it. Their logic is often some variant of, "Making people leave comments under their own names, or otherwise trying to verify their identities, restricts free speech and discourages lively debate." Maybe that's true -- if by "restricts" you mean, "requires that people take responsibility for," and if by "lively debate" you mean, "the impulse to act like a swine or a fool."

Restricting or eliminating anonymity discourages gratuitous jerk behavior, just as the invention of caller ID turned prank phone calls into nostalgic memory. Ninety-nine percent of arguments against anonymous commenting are self-serving rationalizations. Few commenters desire anonymity because their sentiments urgently need and deserve protection. Chances are they're not blowing the whistle on a corrupt boss or a murderous government or going against the grain of their hidebound company or expressing philosophies that are truly heretical. More likely they're people who in daily life get argued with, shut out, stepped on or otherwise treated with less than the reverence they believe they deserve. So they wade into comments sections to act out power fantasies -- the righteous truth-telling antihero, the schoolyard bully, the class clown -- with some assurance that their wife or mom or kids won't find out and ask, "What on earth is wrong with you?"

And yet anonymous comments -- all of them, even the written equivalent of high-speed drive-by shootings -- serve a useful function. They show us what the species is really like: the full spectrum of human behavior, not just the part that we find reassuring and enlightening.

It's impossible for anyone who reads unmoderated comments threads on large websites to argue that racism, sexism or anti-Semitism are no longer problems in America, or that the educational system is not as bad as people say or that deep down most people are good at heart. Unmoderated comments threads are X-rays of the reptilian brain -- indicators of the dark stuff that rattles around in the id and that would get blurted out in the home or workplace routinely if the superego didn't intervene. Mel Gibson's rants are no more ugly than sentiments that get expressed thousands of times a day all over the Internet.

When a person comments anonymously, we’re told, they're putting a mask on. But the more time I spend online the more I'm convinced that this analogy gets it backward.

The self that we show in anonymous comments, the fantasy self, the self we see in the mirror when we fantasize about being tough and strong and feared, the face we would present to the world if there were no such thing as consequences: That’s the real us.

The civil self is the mask.

Shares