It wasn't long after news of the Tucson, Ariz., tragedy broke that the words "paranoid schizophrenic" entered the conversation. Armchair psychiatrists across the country looked at Jared Loughner -- 22, history of antisocial behavior, with a cache of rambling YouTube videos on government mind control -- and diagnosed him. But is there any truth to this? And if so, how does it help make sense of his horrific actions?

To try and untangle the influences that might lead one lone gunman to fire his Glock at a political rally, we turned to Dr. E. Fuller Torrey, respected psychiatrist and one of the foremost experts on paranoid schizophrenics. Torrey has written several books on the mental illness, including the bestselling classic "Surviving Schizophrenia." He is founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center in Virginia, a national nonprofit for the mentally ill.

Quite early in the news cycle, the media more or less diagnosed Jared Loughner as paranoid schizophrenic. Do you think that's accurate?

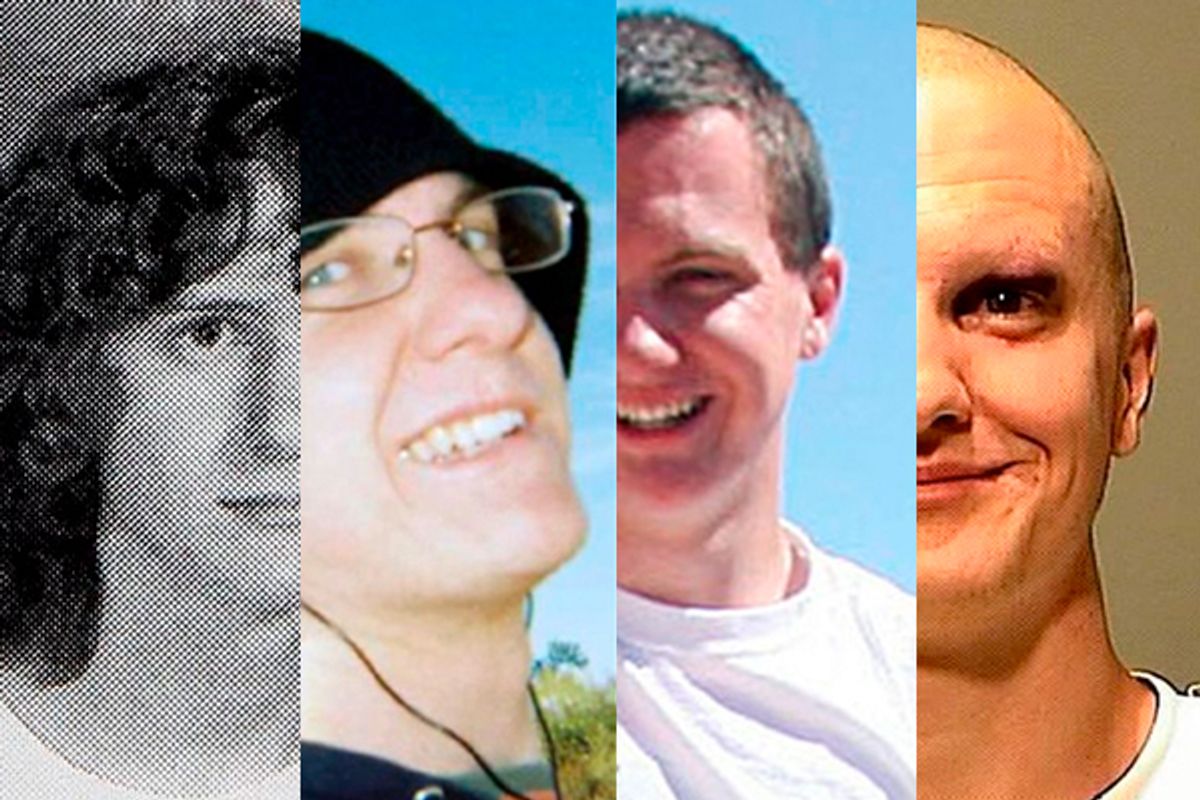

He's a textbook case. Most psychiatrists will tell you they need to examine a patient before diagnosing him, but this guy has all of the symptoms. He has the right age of onset. He has a deteriorating social course, as they say in the [DSM], social and occupational dysfunction. He has delusions, and they're pretty strange. It's common for schizophrenics to think people are trying to control their mind, but thinking the government is trying to control your grammar -- I've never heard that before. The real tip-off is the markedly disorganized speech, which you see in the rambling videos. This is the kind of disorganized speech that you virtually never get in any other condition. It's what we call pathognomonic of schizophrenia. That is, when you hear that symptom, it's "schizophrenia until proven otherwise." He's also got the affective flattening of emotion, which you see in that mug shot.

Let's talk about that mug shot, because it's pretty striking. This guy is getting booked on six murders. Why is he smiling?

That's pretty bizarre, and that's something a person with schizophrenia will do, because their emotions are disconnected from what's going on. When you tell a schizophrenic your mother died, they might smile instead of cry.

Early on, I wondered: Are we jumping to conclusions with this guy's diagnosis? But you're the expert, and you're saying you feel pretty confident.

If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, I will call it a duck until somebody tells me it's really a chicken in disguise. Is there any chance it's not schizophrenia? Sure, but I'll give you 100 to 1 odds.

I was struck by his obsession with "lucid dreaming."

When someone comes in and talks about lucid dreaming, drugs are the first thing I wonder about. But with schizophrenia, you can get almost anything that's weird like that. In itself, it didn't stand out to me.

And there was some evidence of drug use with Loughner. It sounds like he was smoking marijuana, and then got off of it. Did anything stand out to you about that part of the story?

Certainly anyone in his age group using substances is not unusual. We do commonly find that when people have schizophrenia or bipolar they tend to increase substance abuse. I don't know if he's hearing voices, but what I see frequently is young kids hearing voices, and they start using acid or PCP because then they can explain why they're hearing voices. It's a way to avoid the reality that, hey, I'm getting sick.

We have a strong correlation in our minds between schizophrenia and dangerous behavior. What is the real connection between this mental illness and violence?

There is a very small number of people with schizophrenia who are, indeed, dangerous and do things like this. It's very important to emphasize that the vast majority of people with this disease are not dangerous, and there are certain predictors in terms of who will be dangerous. Past history of violence, substance abuse, both of which are predictors for non-schizophrenics, too. But I've followed schizophrenia for 30 years, and I have never seen one of these high-profile homicides where the fellow hasn't been off his medication when he did it. Being off medication is a clear risk factor for people who have a past history.

Then there are certain kinds of symptoms as well. Thinking people are controlling your mind will increase the risk of violence, also having what we call command hallucinations, so that you're hearing voices that tell you to do things.

Whenever these horrible events occur, people often say: Oh, it was probably a paranoid schizophrenic. Why has this behavior become so strongly associated with tragedy?

If you have grandiose delusions [caused by other forms of schizophrenia or mental illness] -- if you think you're the king of Washington, for instance -- you're not likely to kill anyone. If, on the other hand, you have paranoid delusions [consistent with paranoid schizophrenia] and you become convinced that the woman who lives across the street is sending signals into your brain, then you may try to hurt her first.

We've heard a lot of debate about how heated political rhetoric might have led to this. What do you think about that?

I think it's a red herring. We have seen these kinds of things in periods with relative peace in the political environment, we've seen it in turbulent times. I think it's unrelated, frankly.

The only reason we're talking about this today is that he killed six people rather than one person and that one of the people he shot is a congresswoman. These are not uncommon events. People like this man, with likely untreated schizophrenia, are responsible for about 10 percent of the homicides in the United States. That means about 1,600 homicides a year.

The Washington Post published e-mails from one classmate, which described Loughner as the kind of guy "you see on the news, after he has come into class with an automatic weapon." On one hand, I'm struck by how often I've said something just like that, either in jest or being serious. On the other hand, I'm genuinely curious: What do you do when you see someone like this?

That's the $64 million question. Among his classmates, if you took all the information known about him and looked at it together, you'd say this guy is potentially dangerous. But one classmate saw one thing, another classmate saw another. The college apparently had enough information to know this guy should be off the campus if he didn't get mental help. They knew people were purposefully sitting by the door so they could run fast in case this guy did something. This guy clearly struck people as dangerous.

In Arizona the laws are fairly liberal compared to other states. In lots of states the only way you could act on this is if he had demonstrated dangerousness to self or others. But in Arizona, it would have been legal to involuntarily take him to the clinic and have him evaluated. People don't do this much, because we're very concerned about people's civil rights. How do you weigh the fears of a college atmosphere against the civil rights of the individual -- an individual who will go in and say, "Look, I might be a little strange, but there's nothing really wrong with me"?

That's a key question. Did the college behave properly? Should the school have mandated some sort of mental health treatment for him, rather than kicking him out?

Legally, they could have. Whether they should have or not depends on who had what information and what it looked like at the time. The retrospect-o-scope is a hundred percent.

But how do you distinguish between a dangerous schizophrenic and a non-dangerous schizophrenic?

You can't just look at someone and say, "This person is dangerous." The past history of violence is the most important thing, and if they're abusing substances or not taking their medication.

During media coverage of stories like this, we often hear that we should take mental health seriously in this country. What would that mean, exactly?

It would mean you would actually have the resources to do something we haven't done yet, which is get people treatment. We have been very good at emptying the hospitals. What we haven't done is to offer treatment once people are out of the hospitals. In Arizona, for instance, they closed down most of the hospital beds. They are next to last in the United States in the availability of hospital beds for the population, and they have closed down some of the outpatient clinics. If you want to get serious about mental illness, then you need to provide the resources so people can be treated.

And then the tricky question is: Where do those resources come from?

This has been, for 200 years, the state's responsibility. That's why state hospitals were built. This has not been, primarily, a federal responsibility. Ultimately the states are responsible, therefore the governor's responsible, the legislature is responsible. And the Department of Mental Health should be held responsible. This is not rocket science. We know what the good programs are. Everyone has decided: It's better to save money, and we'll close down hospital beds; people who want to get help, we'll try to get them help, but we won't do much more than that. If you keep doing that, you will continue having these kinds of disasters. This is not new. If enough people become sufficiently angry, they will demand that their state government do what they should have been doing all along. Until a sufficient number of people become angry enough, it's not going to happen.

I know this is hard unless you're a doctor, but in broad strokes, what are the warning signs that people should look for?

Bizarre thought processes. Paranoid ideation. People misperceiving your relationship with them, thinking you're following them when you're not at all. If you see evidence of any of that, you may want to change your seat. But this is the tricky thing. These people don't walk around with an "S" on their forehead. They're like you and me, but they've got something seriously wrong with their brain. I've treated everyone from fully trained physicians to high school dropouts. Schizophrenia is an equal opportunity disease.

Shares