The anti-vaccine crusade remains one of the enduring, heart-rending mysteries of our young century. Despite all reasonable evidence showing that failing to vaccinate children puts them at enormous risk, an astonishing number of parents hold off anyway because of scientifically unproven fears that it could lead to the onset of autism or other conditions. More mystifying still: The parents susceptible to vaccine conspiracy theories often are well-educated, liberal-minded denizens -- people just like Salon readers -- in upscale areas like Marin County, Calif., which has the fifth-highest average-per-capita income in the U.S., but whose parents bypass vaccines at three times the rate of the rest of the state; or in Ashland, Ore., where the exemption rate is an astounding 30 percent.

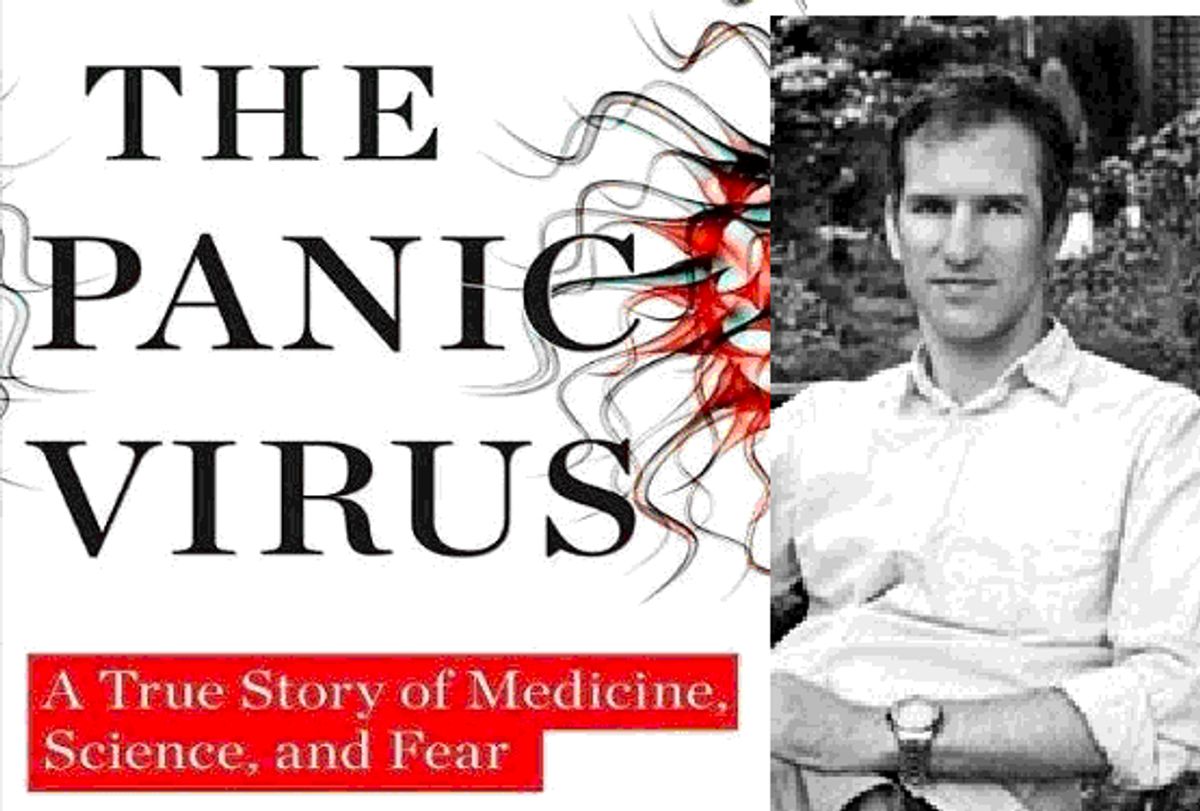

In "The Panic Virus," journalist Seth Mnookin gives a gripping, authoritative account of how the anti-vaccine crusades caught on, shining a bright light on Andrew Wakefield, the now disgraced British researcher whose early work claiming a link between vaccines and autism created a global stir, and authors like David Kirby ("Evidence of Harm") and celebrities like Jenny McCarthy, who hyped the shocking connection long after it had been debunked and Wakefield denounced. (The denouncements continue; this month, the British Medical Journal accused Wakefield of an elaborate fraud.).

Mnookin, a Vanity Fair writer and a longtime media reporter, shines a particularly blinding light on journalists, who have often been too eager to uncritically repeat frightening vaccine conspiracies and, in some cases, publish their own gotcha coverage, exacerbating the panic without the evidence to back it up.

I should disclose here that Mnookin is a friend, and I consider him a friend of this publication, one who wrote for us during his early days as a writer. But that didn't stop him from taking a searing look at the role Salon played in hyping the danger of vaccines. In 2005, we published a report, "Deadly Immunity," by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. that appeared in Rolling Stone magazine (Salon had a co-publishing arrangement with the magazine at the time), in which Kennedy wrote that he "became convinced that the link between thimerosal [a mercury-based compound once used in vaccines] and the epidemic of childhood neurological disorders is real" and set out to make his case that "our public-health authorities knowingly allowed the pharmaceutical industry to poison an entire generation of American children, their actions arguably constitute one of the biggest scandals in the annals of American medicine." In the days after publishing Kennedy's story Salon was forced to run a slate of corrections to errors in his piece. Mnookin effectively describes Kennedy's "egregious ... slicing and dicing" of statements and data in the article. We've come to believe that keeping even the corrected story up on our site is a disservice to the public, and have removed the story from our archives (you can read more about that decision here).

We spoke to Mnookin about how vaccines have become such a persistent, politicized issue, the fraught history of inoculation in this country, and what it's like, as a new father, facing the vaccine question.

You document how the anti-vaccine movement in this country has taken on particular energy with affluent people, in intelligent, liberal communities. Why do they seem the most susceptible to believing the myths about vaccines?

I think it sort of hits a lot of issues that make instinctive sense to more liberal, well-educated people. It's not difficult for me to imagine that pharmaceutical companies do not always have my best interests at heart. Similarly, that big businesses are able to manipulate the governmental profits, manipulate lawmakers in order to effect policies that may not be in my best interest. So I think those are two things that come into play here a lot. And the narrative of parents and children being taken advantage of and being harmed by big business, by big corporations, is a very compelling one. You don't see a lot of movies about the sympathetic drug company.

But your book also documents the long, historic anti-vaccine or anti-inoculation fervor in our history, going back to the 18th century and Cotton Mather, who was ironically a great proponent of early inoculation treatments. Is there a natural American skepticism of anything that government tries to mandate?

I think that what you saw in the early days of the smallpox vaccine and what you've seen since then are slightly different. Because what happened, initially, when the smallpox vaccine was first introduced was …. something that no one had any experience or history with. Or reason, really, to trust. So I think that came into play a lot, and a sort of interplay between that and this American sense of liberty and personal freedom.

Religion too, right?

Well, definitely, at the time, yeah. You don't think of Cotton Mather as being a free thinker, you think of him as being involved in the Salem witch trials. But he was very much in favor of these early inoculation attempts, and he was accused of asking people to side with the devil. And at the time, one of the arguments was that if God wants you to be sick, you should be sick. But since then, it's been a little bit more cyclical in that when you're surrounded by people who are dying or are made incredibly ill by a given disease, people tend to be in favor of that vaccine.

One of the interesting stories in your book, that I didn't know that much about, was the Cutter Labs incident involving the polio vaccine.

It wasn't something I knew anything about either, before I started looking into this. It's a remarkable incident in our history. The Jonas Salk vaccine trials were the biggest medical trials in the country's history. And then, within days [of the early vaccine being released to the public], it turned out that one of the labs had been producing faulty batches, and kids were being paralyzed and in some cases were dying.

And yet it didn't stop people from eventually getting vaccinated.

The fact that the polio eradication effort and polio was eradicated in this country was a sign how pervasive fears over polio were at the time.

People just knew people who were suffering from polio, they had this constant reminder, in their neighborhoods or in their communities, of people who were just in horrible shape or in some cases dying.

It's horrific; you don't need to know a lot of people living in an iron lung to understand how horrific that is.

Do you think that's part of the reason that people today can even consider being anti-vaccine? Because they're not confronted with the possible ramifications?

There are two different answers to that question. One is that obviously, one of the most vocal groups about this has been and is parents who believe that their children have been harmed by vaccines. I think that their outspokenness about this is very understandable, and I do not know what my reaction would be if my child was incredibly sick, and I think our natural inclination is to look for answers. Autism is a really scary disease, all the more so because we don't know its causes, we don't have effective treatments. I think the reaction on the part of those parents is really understandable.

Another thing that makes this so interesting is that this belief that vaccines are harmful is not something that is present in communities that have been personally affected by this. In this instance I think that part of it has to do with children. It can be really difficult to be rational when it comes to children. Especially your own children. I think part of it has to do with a basic misunderstanding of how science functions and what risk means; you know, a real sticking point over this has been scientists' insistence on saying that vaccines are safe "according to everything we know." And the implication there is that tomorrow we might know something else ...

They're really penalized by using careful language.

Yes. Exactly. But it's not good; the reality is that all I can say is that I will not be able to run faster than the speed of light, according to everything we know.

It's the limitation of science.

Exactly. I can say with an enormous amount of confidence that I won't be able to in the future. However, I might be able to in the future. I can't predict everything that could ever happen. You get scientists on TV, they're used to talking in front of a conference or graduate seminars and you contrast that with someone who's more comfortable speaking in absolutes -- even when they're not necessarily supported by evidence -- and as a parent, one of them sounds a lot more compelling than the other. I think that the public health community has some degree of responsibility. I think that there's an assumption early on in this current series of scares that the public would accept the vaccine just because they said so. And that clearly wasn't true. There's no question that we're not in an age in which people are comfortable accepting things just because a so-called expert says that they should. That was something that public health officials didn't realize until far too late. I think that they bear some responsibility for that.

The other entity that you indict pretty strongly is the media and journalists for playing a huge role in propagating a lot of false myths. I should say at this point that you have a really tough chapter devoted to a 2006 article written by Robert F. Kennedy Jr., and which Rolling Stone and Salon co-published. That was a specific case in which the story tried to link autism to the thimerosal. That has been thoroughly debunked by every serious inquiry. Was that report typical of the sort of journalistic problem you saw?

I do think that the media has more -- we have more responsibility for this than really any other single entity. There are a number of reasons for that. One is this false sense of equivalence. If there's a disagreement, then you need to present both sides as being equally valid. You saw with the coverage of the Birther movement; it's preposterous that that was an actual topic of debate. The fact that Lou Dobbs addressed that on his show on CNN is an embarrassment. It's not a subject for debate just because there are some people who said it was. I think you see that a lot in science and medicine, for a number of different reasons including the ways in which it can be hard to explain basic fundamental issues -- so I think that is a huge, huge issue and that's the huge issue that doesn't come into play in the story. And I think it's an absolute cop-out for reporters to say, "I've fulfilled my responsibility by presenting two sides." Sometimes there aren't two sides.

The false equivalency comes into play, really, in the situation of the MMR [measles-mumps-rubella] vaccine with Andrew Wakefield; you had him and a handful of researchers versus millions of doctors and researchers. I'm not talking about initially when his study first came out, but several years later when there had been all of these follow-ups. And obviously, you can't quote millions of doctors in one story; on the one hand this person thinks this, and this person thinks this. You're not talking about one person versus another. If I said that, oh, I have a report that Derek Jeter's going to quit baseball, no one would run that because it would be embarrassing. Because there's no information to support it. If I said that I have good information that Boeing is about to buy IBM, you know, people wouldn't run that. But for some reason when it comes to health and science, you don't get that. Instead of feeling embarrassed by running stories that people agree aren't true, it's kind of like, oh, we want to get out ahead of this controversy.

Then there's the other type of reporting in which (and this is true of a lot of journalists) they're looking for a really good story, and maybe they have preconceived notions about the way government works and you know corporations tend to be out for their own interest, not the public's interest. That's a different kind of journalism that created problems on the story.

Definitely. And I think that gets to another issue that comes into play with science and medicine. I'm not entirely sure why this is, but more so than in other areas there is a willingness to have people write about and cover these issues who don't have any background in them. You wouldn't ask me to go write about hockey, because I don't know anything about hockey. But if something came in over the wire about a cancer study, often times, especially now with the cutting of science sections, that assignment could end up on a general reporter's desk. You wouldn't ask me to cover business or the movie industry without knowing something basic about it. I don't know how this happened, but I think there has to be some sort of movement away from, oh, like, we're going be the first ones with this juicy story. And then in the days and weeks to come, we'll figure out what the reality is as to, you know, what it would be really embarrassing if we were the first ones on a story that ends up being completely ridiculous. And ultimately, that's going to hurt our credibility with viewers, readers, whatever.

If you go on the Web and really spend much time going on Google news, for example, on autism, though, most respectable publications that immediately pop up quickly dispute any kind of link with vaccines. And yet, people still are drawn to this conspiracy.

Today, most of them do. It's sort of like putting the genie back in the bottle. For years that wasn't the case. For years you had stories saying that computers lead to brain cancer. Even if now most outlets said, no, you know what, computers actually don't lead to brain cancer, I think it would be much harder to sort of dispel that. It's the same thing with Obama and the Birther movement. Most outlets now certainly say that he was born in the United States. But once it's introduced as a topic of discussion it's really hard to un-introduce it.

I was surprised when, while you were on CNN recently, you were asked whether or not there were any peer-reviewed articles that linked autism with vaccines. It was kind of shocking seeing that on TV at this point, because of course there hasn't been. It's interesting that media figures still don't seem comfortable just saying, "This isn't true," that they need a guest on their show to reiterate that it's not true.

That whole segment, and in fact all of the coverage last week, is a really good example of what happens. The coverage has been that this study that linked the MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent. But if you look at the story arc, especially on TV, most of it has been OK, so, is there anything to this? Well, no, we've known for years there's nothing to this. Wakefield lost his right to practice medicine over a year ago.

It's a weird déjà vu. It's almost as though the latest report debunking the conspiracy almost gave credence it, just by giving Wakefield another chance to make his case.

Well, and not only that, understandably, if a year ago, you saw "autism and vaccines, the link is disproved" and a year later if you see the same story, you'd feel like, wait a minute, was not this true last year? Next year they tell me this again, and what does that mean about what they're telling me now?

When things seem always in play, there's always a question of what the truth is. So how should this most recent story have been played?

I think a way would have been something like, "The researcher who promoted a link between the MMR vaccine and autism that was disproven years ago is now under further fire for a new series of problems with his initial work." Not, "Now, this study is shown to be fraudulent." The study was shown not to be accurate years ago. It could not be accurate because of shitty data, because of bad research practices, any number of things, because he's a fraud. It was shown not to be valid years ago.

You spent a lot of time with these anti-vaccine groups. And you know the science, you know the logic, you know what's true in this story. Was it frustrating interviewing them; were you constantly fighting the urge to shake them and argue with them?

When I went into this, I actually didn't know -- which I think is sort of emblematic of part of the problem. I consider myself fairly well-educated. But I started researching it because I actually had no idea and was surprised that there was so much disagreement about something that there had to be factual evidence on. It wasn't like people were saying there was a middle ground.

During a lot of my research, I didn't feel like I had this certainty that I do now. Because it takes a long time to read through years of scientific reports. But I found it very frustrating at times to talk to people like Andrew Wakefield. There was this certain whack-a-mole quality to his arguments. Parents, especially parents of children who were either autistic or children who are ill for some other reason, I didn't get frustrated with because I think that they are coming from a genuine place, and they want to protect their kids. They believe that there is a connection between vaccines and what happened to their children.

One example that I thought was fascinating and, for me, was very telling, was there were these enormous omnibus court trials in what's called vaccine court. It involved thousands of families who were suing, and the [alleged] crime was that their children had been made ill by vaccines. And there was one family that was kind of a test case for the omnibus hearings and the mother testified about what had happened when her daughter was a year old and 9 months old, and 15 months old. And in this case, there actually were videotapes and contemporaneous records of that child, and the mother's recollections didn't match up with the videos. I don't think that she was being dishonest at all. I think that's what human beings do: We order things in our brains in ways that make sense. I'm not immune to that; I do things like that, too. I didn't find that frustrating. I found it upsetting, a lot of times. And I found that the sort of overall tenor and viciousness of the debate to be upsetting. But I didn't get frustrated talking to the parents in that same way. You said that I was really hard on people in the media, and some very specific people, and I think that's because I did get frustrated in those instances. And I thought that was irresponsible.

Your son is now over a year old. Have you had any hesitation about getting his vaccines?

No. You know, that said, obviously you can't tell a 3-month-old or a 6-month-old that this is all going to be fine, and that you're not trying to hurt him. I found it excruciatingly painful. I definitely wanted to grab him and run.

Explain that -- why?

Not because I thought that he was going get sick, just because here's this tiny creature that it's my job to protect him, and something's going to happen to him that's going to hurt. That was horrible. I hated it. I found that to be very difficult. I wasn't worried about the potential side effects. And I am worried about what the side effects would be if he wasn't vaccinated. But I did find the whole experience of bringing him so someone could stick a needle in him, to be a difficult one.

Shares