"All those James Bond movies."

This was Katerina Brunot's response when asked about the appeal of Russian women. Her voice was relaxed, and a decade after experiencing the terror of her mail order marriage, she could afford some humor.

I spoke with Katerina not long after discovering that the largest introduction service for Russian women, Anastasia International, lists its United States headquarters in my home state of Maine. It was a weird day, that one.

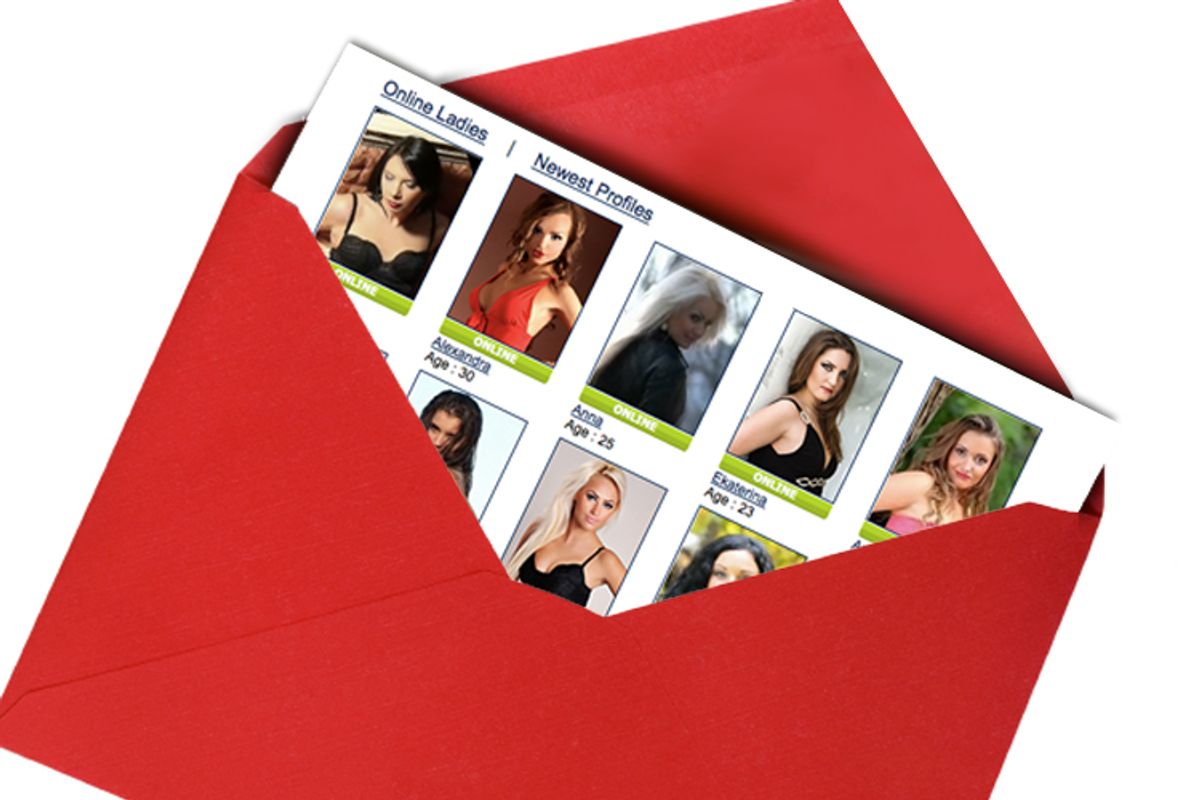

I was online when a pop-up ad arrived on my computer screen, and a woman with thick lipstick in a cleavage-baring interpretation of a Soviet military uniform invited me to click. When I moved to close the window, I recognized the contact address. Or rather, I recognized the city: Bangor, Maine. Bangor is home to horror icon Stephen King and breakfast specials at Nicky's Cruisin' Diner. But a Russian mail order bride business in rural Maine? I needed to know more.

These days, sites like Match.com and eHarmony, not to mention Craigslist and Facebook, have turned coupling across great distances into a casual and daily event. But long before the explosion of the Internet there was another way people in different countries could forge a union, so popular yet strange that it became a regular punch line: mail-order brides. The practice dates to the earliest pages of world history when marriage was, at its core, a business transaction, and middlemen (or women) were paid a fee to provide access to like-minded individuals. The same system thrives today, except now these cross-continental, money-motivated matchmakers are more commonly referred to as international marriage brokers, and these marriage brokers represent a multimillion-dollar global industry. These organizations promote unions with Latino, African, Asian and Filipino women, but the market for educated, European white women who can assimilate into largely Caucasian communities has pushed the appeal of Russian love to the top of the commodity list.

The phrase "Russian brides" conjures sensational impressions of murder, corruption, organized crime, immigration scams, prostitution and, as Katerina points out, James Bond fantasy. It's no wonder the media loves the story: In the past few months, I watched Russian mail-order brides featured by the "Today" show, as a joke on the sitcom "Mike & Molly," on the National Geographic Channel’s "Inside," and in a "Tyra Banks Show" rerun. But I wanted to get past the punch lines -- I wanted to meet the real people. What I discovered was a fascinating, and problematic, industry that has a small Maine connection but stretches across the world. As I delved into the subject, no story haunted me more than that of Katerina Brunot.

Ten years ago, Katerina was 22 and studying art in Siberia when she advertised in a catalog. "I live a healthy lifestyle, am romantic, kind, honest, faithful, and loyal," she wrote beneath a photo of herself in a black blouse, blond hair framing her smiling young face. Hoping for adventure and love, she had no specific goal to move to the United States. Her hometown, Novosibirsk, although extremely remote, was in the midst of an economic boom, and it remains a bustling city similar in size and culture to Chicago.

In her advertisement, Katerina listed "old-fashioned values" and although unknown to her at the time, that phrase is often code in the international matchmaking community for docile, submissive and deferential -- the perceived opposite of American women. Her old-fashioned values caught the attention of 45-year-old plumber Frank Sheridan from Atlanta, and that's when her ordeal began.

Sheridan wooed Katerina with flowers and gifts, but when he arrived in Siberia, Katerina noticed immediately that he appeared older than his photos.

"Older, unhappier, not as much exciting as in the letters or over the phone."

But during the initial 10-day visit, Sheridan seemed to soften. He referred to Katerina as his Siberian princess, and as a result of his apparent kindness, she saw him through hopeful and optimistic eyes. Within a year, she was married and living in her new American home. That's when Sheridan told her the reason he brought her to the United States was for housekeeping and sex.

She was beaten and forced to spend her days cleaning Sheridan's house with exacting precision, while he reminded her of the money she cost him. When she tried to escape, he stabbed himself and accused Katerina. Because of her limited grasp of the English language, she did not understand the responding police officers, and she was arrested and jailed for nearly a month. Katerina eventually found a women's shelter, but Sheridan stalked her relentlessly, hid her documents, harassed and tried to deport her.

When police initially attempted to arrest Sheridan for aggravated stalking, they discovered he was in Russia, courting a new bride. During a second arrest attempt, Sheridan shot the police officer, who shot back, and Frank Sheridan was dead.

Katerina was a victim in the world of international marriage, and she offers her experience as a cautionary tale to other women.

"I was not prepared for what could happen."

In 2006, the International Marriage Broker Regulation Act (IMBRA) was enacted as a means of protecting foreign women like Katerina. The law is complex, but among its mandates, it requires a client check against the National Sex Offender Public Registry, a lifetime cap of two visa petitions per male client and a shift of responsibility to the organizations involved. Five years after IMBRA was enacted, most U.S.-based international online dating sites now boast their often reluctant compliance, and those that don't have closed or moved their operations offshore.

There are hundreds of international matchmakers, and they exist on a spectrum of motives, from altruistic mom-and-pop kitchen groups to highly predatory human traffickers. One of the more reputable sites, Anastasia International, is the organization with its stateside office in Maine, and to be clear, this was not the organization associated with Katerina's ordeal.

Anastasia International is one of the world's largest international marriage brokers with nearly 460,000 male clients -- for reference, this male client base is larger than the entire population of Miami. It counts more than 25,000 female clients, and the vast majority of these women hold at least one undergraduate degree, are older than 25, and many have children from previous relationships -- an educated, relatively mature population of women looking for love in a forum where American men skew heavily in their favor.

The IMBRA legislation is a sticking point for the company, a measure it considers costly and disproportionately onerous. General manager Dan Sykes asked me to think broadly about the topic. He noted that a domestic Internet dating or a social networking company would never be required to gather private background information from, or potentially be held liable for, the criminal actions of its clients.

"But what about the abuse?" I asked, citing Katerina. "Do you feel a responsibility for women like her?"

His features softened, and reminded me again that Katerina was never a client of his. He shared that he supports the need for protections, but the law, as written, labels each of his male clients as potential abusers when the percentage of domestic violence in his industry is no higher than the general population. In fact, the percentage of reported abuse cases is significantly smaller. To insinuate differently, he says, is unfair.

An estimated 11,000 to 16,500 women arrive in the United States each year as a result of international marriage brokers, and this labeling is an issue for Dan. "I don't get involved with my clients," he said. "I consider my business a communications and translation company. We do not make matches or arrange marriages in any way."

He emphasized that his company does not chaperone clients or facilitate the visa process, nor is there financial incentive for marriage. "We profit when clients communicate and attend social functions. Period. We operate a website where interested parties can meet."

"Like online dating for a specific clientele?" I asked.

"Exactly," Dan said. "So why is my business labeled as a marriage broker when we don't broker marriages?"

With 230 employees and 400 contractors between the United States and Russia, 35 working in the fraud department, Anastasia International is actively trying to change the industry's negative image, and it operates with a focused goal: profit.

Male clients pay a fee to register at Anastasia International's website. They browse profiles of Russian and Ukrainian women, and then they buy credits, which are used to communicate. Each credit costs $3, and translation assistance can also be purchased.

Additionally, there are romance tours where men travel to Russia and attend a series of social events designed for them to meet eligible women, but this aspect represents just 5 percent of Anastasia International's overall revenue.

For those who respond, "ick," consider this: The United States was founded on the same transactional nature of mail order brides when, in 1619, the Jamestown Colony received its first shipment of white women in exchange for tobacco crops. Or more currently, in-person singles mixers are frequently advertised at bars in nearly every city. Men will happily pay a cover charge to access a roomful of eligible women.

Sex for money tends to be a black and white issue, moralized and legislated into distinct camps of right and wrong. Selling romance, on the other hand, or the prospect of it, is a lighter shade of gray. This transactional nature of romance -- the idea that people will pay, handsomely, for the luxury of finding love in the form of a Russian woman, is the type of commodity thinking that underscores action.

Jeanne Smoot is the policy director at the Tahirih Justice Center, and the center's mission is to provide legal protections from abuse for immigrant women and girls. They offer direct legal services (leveraging both in-house and pro bono attorneys) as well as national public policy advocacy.

Jeanne witnesses, firsthand, horror stories of "brokered" marriages.

"Women are described like commodities -- one company pushes a package they offer as a 'Fresh Hot Sampler Plate,' like you can get at a restaurant."

She handed me printouts of advertising material from several international marriage broker websites. They ranged from poorly spelled to flat-out perverse, a vast cry from Anastasia's site, which touted its gorgeous women, sure, but also its IMBRA compliance and professional tone.

"Companies often hype the sexuality and submissiveness of these women, and that can appeal to men seeking someone they think they can control and abuse," she said. "When a man finds a woman in a catalog and is offered 'money-back' or 'satisfaction' guarantees, he feels ownership of that woman." Jeanne continued, "That sense of ownership very often leads to abuse. It's a pretty direct link."

I have Jeanne's printouts on my desk, and one of the most disturbing is this: "Having also been accused of asult (sic) by western women, who are usually the instigaters (sic) of domestic violence I can tell you … don't let it bother you." "It" is a history of violence, and the note is meant to reassure a potential client that his violent criminal history will not be a problem in securing a foreign wife.

As I read those vile words, I committed to a stance: This industry is far from benign, and it can be extraordinarily dangerous. The immigration scams, predators and crime all happen. But that's the easy position: the punch line. I also committed to the more difficult approach: to look with compassion at the people involved.

Russian women, often highly educated, are not all out to scam men for green cards -- they want to fall in love. So do the men. And sometimes, people find a happy ending.

I was invited to Olga Russell's home for supper. She met her husband, David, through an international matchmaking organization and recently celebrated 10 years of marriage. Both Olga and David claim that without the service, they never would have met.

"Here in the United States," Olga noted, "if you are healthy, you can find a job and an apartment and a good life. In Russia, this is not always so. There is not always the same starting point."

Olga celebrated her 40th birthday in Russia, and although the Iron Curtain had fallen, details of her life had changed very little. She worked each day as an engineer, designing components for a tank-manufacturing facility.

At 40, she was single with the misfortune of being born in a postwar economy. World War II had decimated a full generation of 23 million Russians. As a result, a woman -- even one as spry, educated and beautiful as Olga -- expected to be single. She loved her city, and she loved her country, but she also wanted romance and a husband of her own.

"There were no men," Olga stated, shaking her head for emphasis, "and I was lonely."

This is how she happened to approach a matchmaker in the earliest days of Internet romance, before semantic nuance, legal definitions and federal legislation. As she spoke, her husband entered the kitchen. David is much taller than his petite wife, and he reached down to give Olga a hug. Olga returned the hug with a small pat on his belly.

"My tall, handsome husband. See?"

Shares