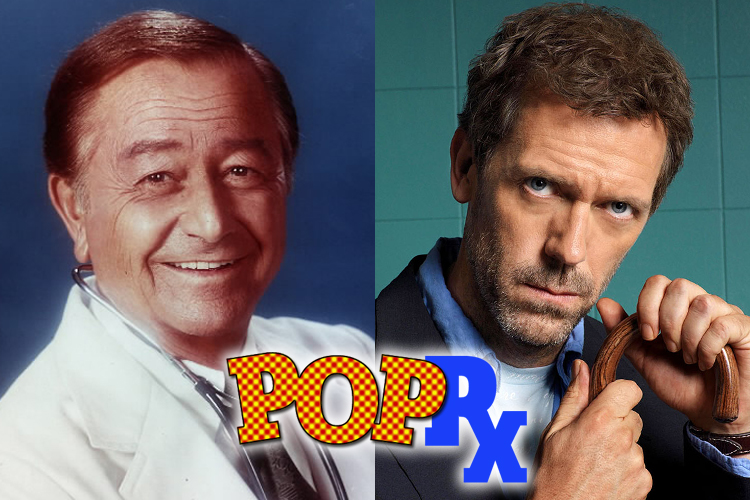

Is there a more iconic symbol of the physician than the white coat? Think of America’s most famous fictional doctors: Marcus Welby, Dr. John Carter, every soap opera doctor who ever graced daytime. They’re always moving through the halls in that authoritative white coat, so crisp it could have come only from the props department of the TV studio. But the white coat has been under a bit of an assault, its status waning for at least two decades (a bit like doctors themselves). It’s telling that one of today’s most popular TV physicians, Dr. House, doesn’t wear one. It’s a sign not only of the character’s eccentricity, but also of our changing attitudes toward the medical profession.

White coats didn’t start out as anything more than a practical piece of clothing. In the late 19th century, surgeons wore white short-sleeved jackets over their street clothes — the beginning of aseptic techniques to minimize infection. Longer coats emerged later, inspired by scientists working in microbiology labs. These, too, were practical, but they gave the doctor an official air as well. In the 19th century, medicine was in its nadir, overrun with quacks and phony tonic salesmen. In response, reputable but frustrated physicians moved to debunk these charlatans and resurrect medicine’s reputation by aligning it with science. And the lab coat as the symbol of modern, rational medicine was born. Initially these coats were tan in color, but as America headed into a new century, white became the color of choice — pure, true, even angelic, befitting the heroic role these doctors played: putting patients under anesthesia to operate and then resurrecting them, miraculously cured.

But medicine has changed over a generation — and so has doctors’ standing. The image of the doctor as omniscient and omnipotent became harder to uphold. When infection caused most of the country’s illness and death, physicians could quickly save lives with antibiotics. The development of vaccines rapidly cured once fatal illnesses like measles and polio. Then, out with the acute and in with the chronic: diabetes, heart disease, cancer, etc. Hospitals transformed from a holy grail of healing to a place where one has to go — again and again — for continuous tests and treatments. And chronic disease management — vomiting, hair loss and chemotherapy — causes its own suffering. Doctors have become increasingly transparent and guess what? We make thousands of mistakes each year, some of which seriously injure or kill patients. We struggle to stay smart because as our understanding of disease has gotten more complex, we can’t keep all the facts — many of which often conflict — stuffed in our heads.

Power shifts have also occurred. In the past, it was a man’s world, and the white-coated elite ruled over all — nurses, patients and students. Today, women constitute 50 percent of medical school graduates, nurses have made sure that doctors show RNs more respect (deservedly so), and patients are more assertive of their rights as partners in their own care. Health care has also become more fragmented. Whereas in the past, it was a doctor-nurse dyad managing a patient, today, it’s doctor, nurse, medical assistant, nurse manager, social worker, dietician, respiratory therapist, lab tech, nurse practitioner (and the list goes on).

Ironically, recent studies have shown that white coats, particularly the pockets and sleeves, can hold significant reservoirs of bacteria, making the very garb we wear to prevent the spread infection one of the best vessels for it. In 2008, the UK’s National Health Service banned the white coat and instituted a whole new dress code for its docs and medical staff. In addition to banning the coats, the NHS also banned long-sleeved shirts for similar reasons. The American Medical Association is exploring similar changes, but it cites a lack of strong evidence, as well as the fact that professional attire like white coats give doctors some legitimacy and patient confidence.

I don’t know what happened to my first white coat — like a lot of things, it got lost along the way from being a young, naïve and idealistic medical student to an attending physician who knows that the more you see, the less you know. After the rush of having one wore off (it took one nasty call night), the white became more functional — I had to have enough pockets to hold onto my reference books, notes, pens, stethoscope, beeper, etc. I definitely didn’t wash it enough, and I had no shame of wearing it with a coffee or ketchup stain.

Since becoming an attending physician, I haven’t put one on because I have an office to keep all those things in. Also, most pediatricians specifically don’t wear them because we’ve been told that little kids find white coats threatening. But it turns out that’s a myth: Studies actually say they prefer that their doctor wear one.