Initially, the dawn of the Atomic Age came in the form of two mushrooms clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, ending the Second World War. But in the years immediately following the war, while the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists was raising red flags about the dangers of nuclear weapons and warning of the impending arms race, hundreds of postcards were being produced to ramp up support for -- or soften the message about -- atomic energy, and its unfortunate byproduct: weapons of mass destruction.

Initially, the dawn of the Atomic Age came in the form of two mushrooms clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, ending the Second World War. But in the years immediately following the war, while the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists was raising red flags about the dangers of nuclear weapons and warning of the impending arms race, hundreds of postcards were being produced to ramp up support for -- or soften the message about -- atomic energy, and its unfortunate byproduct: weapons of mass destruction.

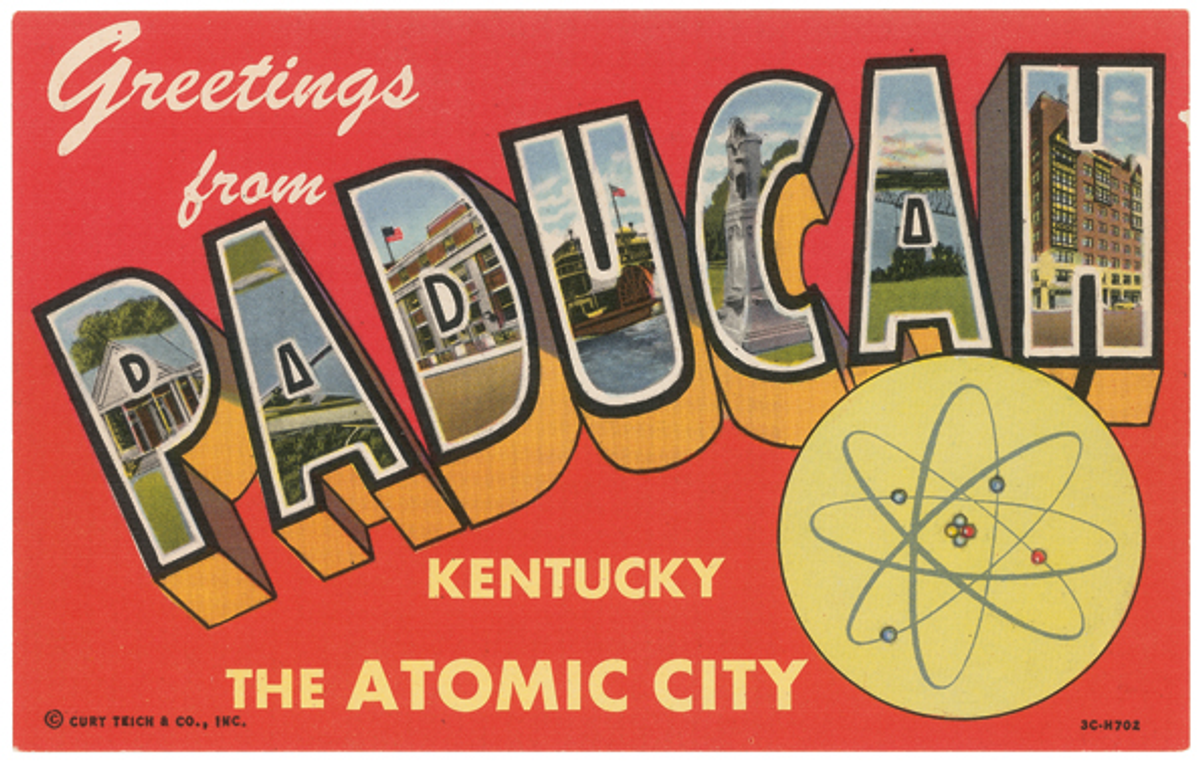

In a sense, the atom became a tourist attraction or a bragging right despite the paradoxical absurdity of the notion itself. A stunning new book, "Atomic Postcards" (Intellect/University of Chicago Press), brings together dozens of atomic propaganda from countries as diverse as Belgium, Britain, Canada, China, France, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Philippines, Russia (then the Soviet Union), Switzerland and the United States.

Edited by John O'Brian, a professor of art history at the University of British Columbia, and visual artist Jeremy Borsos, both Canadians, "Atomic Postcards" documents a treasure trove of these Cold War relics, some which need to be seen to be believed.

At what point did the project become a book idea? Or did it begin as a book project?

John O'Brian: I first addressed atomic issues in 2003, while giving a Levintritt lecture at Harvard. Part of the lecture reflected on the attitudes of the Abstract Expressionists to the atomic era in which they worked. The lecture caused a minor stir, which encouraged me to inquire further into matters of atomic representation. I asked Jeremy to collaborate with me in building an atomic archive. He purchased several postcards online before we realized that we had stumbled on an unexplored genre. He kept looking for cards and by 2008 we had built a substantial collection. The book followed from that.

Jeremy Borsos: The project began with John frequenting my home with visits that coalesced around things artistic and historic and their various readings. He was ensconced in things atomic before the postcards, and was finding ways of translating the postwar moment visually into an elevated conversation that superseded the predictable.

So the things I started looking at for him were items like the first color photographs taken by the U.S. Navy of their atomic tests, but also photographs of the first Bikini show -- meaning the bathing suit as a namesake of what officially was referred to as "Operation Crossroads" -- a test in Bikini Atoll in the South Pacific. Eventually I built up a diverse collection of about 200 items.

We were our own worst enemies, spurring each other into the collecting of and translations into visual commentary of the period between 1945 and 1980. There seemed to be a large variety of postal history encompassing the subject, and a separate archive of postcards was suggested by John, who fortunately for me took stewardship of the many boxes of stuff collected.

Were you two friends previously? Or were you bonded by the artwork of the atomic age?

John O'Brian: Yes. In 2003, I wrote an essay for the exhibition catalog of Jeremy's compelling show, "Then Again," which consisted of a series of large photomontages. The works combined photographs of real estate sites with those of envelopes addressed to the same sites at an earlier date.

Jeremy Borsos: We were friends previously and bonded not only over things atomic, but generally within the context of contemporary art language.When John and his wife, Helen, moved near me, I was thrilled to meet them. In fact, I think I met Helen when she saw me reconstructing a huge 19th century architectural fragment in a field to photograph as a project. John and I met at a gathering, where I showed him a small project, which he immediately supported.

Both of you are Canadians. Canada does not possess any weapons of mass destruction. In fact, it repudiates their use. Personally, are you two opposed to nuclear weapons?

John O'Brian: At the end of World War II, Canada was an atomic power. It also wished to build its own nuclear arsenal following the war; it possessed the necessary scientific expertise and material resources to do so. Prime Minister Mackenzie King opted against the pursuit of a nuclear weapons program, choosing instead to steer a wobbly course between building and banishing the bomb. Canada never joined the nuclear armaments club -- membership is restricted to those countries producing nuclear weapons -- but it did become a major supplier of uranium, nickel and other natural resources crucial to the weapons programs of the United States and Britain. In addition, through long-term agreements, it turned over its coastlines and landmass to the United States for use as proving grounds for nuclear missile and submarine testing; partnered in the construction of three early warning radar systems, including the DEW Line in the arctic, to sound the alarm against Soviet bomber attack; accepted American nuclear-tipped Bomarc missiles on Canadian soil; and exported Canadian nuclear expertise around the globe in the form of the CANDU reactor.

I am personally opposed to nuclear weapons, even if my country has been unsure about the matter.

Jeremy Borsos: "Opposed" to nuclear weaponry doesn't quite contain the degree of embarrassment I feel. Even as a teenager I joined in anti-nuclear marches, and attending a Quaker boarding school secured my loathing of the nadir of human invention that is weaponry of the nuclear variety. I would like to think that Canada's nuclear opposition is and has been complete, but rather, it has been complicit. Ask John about Yellow Cake...

How did you two come to collect these postcards? Where did you find the majority of them?

John O'Brian: I have been a collector of visual histories my entire life, eventually directing their use to creative ends. Previously I collected postcards with multiple criteria in mind. John's interest in the subject of Cold War imagery from a contemporary art perspective ignited a mutual foray into exploring the graphic delivery of the subject as well as its intellectual legacy.

The content of the cards is outrageous yet we hold them in our hands in an intimate way. The format of a book supported the proximities of the original reading of a postcard while allowing us to frame them with adjoining text.

Then there is eBay. The online auction site has changed the world of collecting and helped form strong collections much more quickly than in the past. That is where I found most of the cards. Several years ago, atomic-related material were plentiful.

Cards were often acquired with the greatest of ease, as other collectors' criteria seemed vague. My only true nemesis was a single collector, a nuclear physicist, who frequently outbid me but ended up lending us what we had lost to him. The collection took a little over four years to assemble, along with some scouring of European and Japanese flea markets, and a few more cards borrowed from more diverse collections of material.

Some of the postcards are interesting from a graphic design point of view. The Greetings From ... selections, in particular, send chills down my spine. Do you have favorites among the collection in the book? And why?

Jeremy Borsos: What the postcards represent is both horrendous and strangely benign at the same time. One of my favorites is the black-and-white halftone image of the Cedar Hill Elementary School in Oakridge, Tenn. (the "Atomic City"). Graphically, it has the visual comfort of an image from a small-town newspaper. It epitomizes the social acceptance of Mutual Assured Destruction.

Then there is the Hoyt B. Wooton Bomb Shelter, also in Tennessee, fitted out with Eames chairs and a ping-pong table, suggesting that life hiding from nuclear attack need be no different than life in a suburban rec room. An "insert" in the upper-right corner of the card draws viewers' attention to the facility's modernist architecture. The handwritten message on the back of the card is scrawled in a child's hand. It is for "Aunt Clara." Too perfect.

*All images are from "Atomic Postcards" and courtesy of the authors.

Copyright F+W Media Inc. 2011.

Salon is proud to feature content from Imprint, the fastest-growing design community on the web. Brought to you by Print magazine, America's oldest and most trusted design voice, Imprint features some of the biggest names in the industry covering visual culture from every angle. Imprint advances and expands the design conversation, providing fresh daily content to the community (and now to salon.com!), sparking conversation, competition, criticism, and passion among its members.

Shares