I don't know about you, but the chirpy tales that dominate the public discussion about aging -- you know, the ones that tell us that age is just a state of mind, that "60 is the new 40" and "80 the new 60" -- irritate me. What's next: 100 as the new middle age?

Sure, aging is different than it was a generation or two ago and there are more possibilities now than ever before, if only because we live so much longer. it just seems to me that, whether at 60 or 80, the good news is only half the story. For it's also true that old age -- even now when old age often isn't what it used to be -- is a time of loss, decline and stigma.

Yes, I said stigma. A harsh word, I know, but one that speaks to a truth that's affirmed by social researchers who have consistently found that racial and ethnic stereotypes are likely to give way over time and with contact, but not those about age. And where there are stereotypes, there are prejudice and discrimination -- feelings and behavior that are deeply rooted in our social world and, consequently, make themselves felt in our inner psychological world as well.

I felt the sting of that discrimination recently when a large and reputable company offered me an auto insurance policy that cost significantly less than I'd been paying. After I signed up, the woman at the other end of the phone suggested that I consider their umbrella policy as well, which was not only cheaper than the one I had, but would, in addition, create what she called "a package" that would decrease my auto insurance premium by another hundred dollars. How could I pass up that kind of deal?

Well ... not so fast. After a moment or two on her computer, she turned her attention back to me with an apology: "I'm sorry, but I can't offer the umbrella policy because our records show that you had an accident in the last five years." Puzzled, I explained that it was just a fender bender in a parking lot and reminded her that she had just sold me an insurance policy. Why that and not the umbrella policy?

She went silent, clearly flustered, and finally said, "It's different." Not satisfied, I persisted, until she became impatient and burst out, "It's company policy: If you're over 80 and had an accident in the last five years, we can't offer you an umbrella policy." Surprised, I was rendered mute for a moment. After what seemed like a long time, she spoke into the silence, "I'm really sorry. It's just policy."

Frustrated, we ended the conversation.

After I fussed and fumed for a while, I called back and asked to speak with someone in authority. A soothing male voice came on the line. I told him my story, and finished with, "Do I have to remind you that there's a law against age discrimination?"

"Would you mind if I put you on hold for a few moments?" he asked. (Don't you love the way they ask you that, as if you have a choice?) When he came back on the line, he told me he'd checked the file and talked to the agent who couldn't recall saying anything about age, nor was there anything about it in the record.

"OK," I said, "then sell me the umbrella policy."

"No," he was very, very sorry for the misunderstanding, but they never sell an umbrella policy to anyone who's had an accident in the last five years, and their policy is "absolutely age-neutral."

And if you believe that, I know a bridge in Brooklyn that's for sale.

Makes you wonder, doesn't it: Where are all those sources of personal power and self-esteem we keep hearing about as the media celebrate the glories of the "new old age"?

That's one from my file of personal stories about ageism, but there are other older and bigger ones: discrimination against older workers in the job market among the most important. True, the law now offers a possible remedy in the form of an age-discrimination lawsuit, but who's going to pay the legal and household bills during the years it will take to work its way through the courts? Who's going to help those workers deal with the psychic wounds that come from being so easily expendable, so devalued just because of their age?

In her groundbreaking book "The Coming of Age," published in the early 1970s, Simone de Beauvoir spoke passionately about the stigma of old age -- about the loss of a valued identity, our fear that the self we knew is gone, replaced by what she called "a loathsome stranger" we can't recognize, who can't possibly be the person we've known until now.

Her words give life to a core maxim of social psychology that says: What we think about a person influences how we see him, how we see him affects how we behave toward him, how we behave toward him ultimately shapes how he feels about himself, if not actually who he is. It's in this interaction between self and society that we can see most clearly how social attitudes toward the old give form and definition to how we feel about ourselves. For what we see in the faces of others will eventually mark our own.

As a sociologist, I have been a student of aging for four decades; as a psychotherapist during this same period, I saw more than a few patients who were struggling with the issues aging brings; as a writer I've written about the various stages of life, including a memoir about aging daughters and mothers. Yet until I undertook the research for my recent book, "60 on Up: The Truth About Aging in America" -- until I began to read more deeply and to interview people more systematically -- I didn't fully realize how much ageism had become one of the signature marks of stigma and oppression in our society.

Nor did I really get how much the cultural abhorrence of old age had affected my own inner life. So it was something of a surprise when, as I listened to the stories of the women and men I met, I found myself forced back on myself, on my own prejudices about old people, even though I am also one of them.

Even now, even after all I've learned about myself, those words -- I am one of them -- bring a small shock. And something inside resists. I want to take the words back, to shout, "No, it's not true, I'm really not like them," and explain all the ways I'm different from the old woman I saw pushing her walker down the street as she struggled to put one foot in front of the other, or the frail shuffling man I looked away from with a slight sense of discomfort.

I know enough not to be surprised that I feel this way, but I can't help being somewhat shamed by it. How could it be otherwise when we live in a society that worships youth, that pitches it, packages it, and sells it so relentlessly that the anti-aging industry is the hottest growth ticket in town: the plastic surgeons who exist to serve our illusion that if we don't look old, we won't be or feel old; the multibillion-dollar cosmetics industry whose creams and potions promise to wipe out our wrinkles and massage away our cellulite; the fashion designers who have turned yesterday's size 10 into today's size 6 so that 50-year-old women can delude themselves into believing they still wear the same size they wore in college -- all in the vain hope that we can fool ourselves, our bodies and the clock.

If you still need to be convinced about the ubiquity of the assault on our sensibilities by the anti-aging crusade, try plugging the term "anti-aging" into Google. Last time I checked, it came up with 22,600,000 hits, among them the website of the recently spawned American Academy of Anti-Aging Medicine with a membership of tens of thousands of doctors whose business is selling the idea that aging is "a curable disease." Never mind that the American Medical Association doesn't accord legitimacy to this organization or its stated mission, it continues to laugh all the way to the bank.

There, also, you'll find the latest boon to the American entrepreneurial spirit: a growing array of "brain health" programs featuring brain gyms, workshops, fitness camps and "brain healthy" food. And let's not forget the Nintendo video game that, the instructions say, will "give your prefrontal cortex a workout."

Will any of this help us remember where we left our glasses, why we walked into the bedroom, or the story line in a film we saw a few days ago? Not likely, as recent scientific evidence tells us.

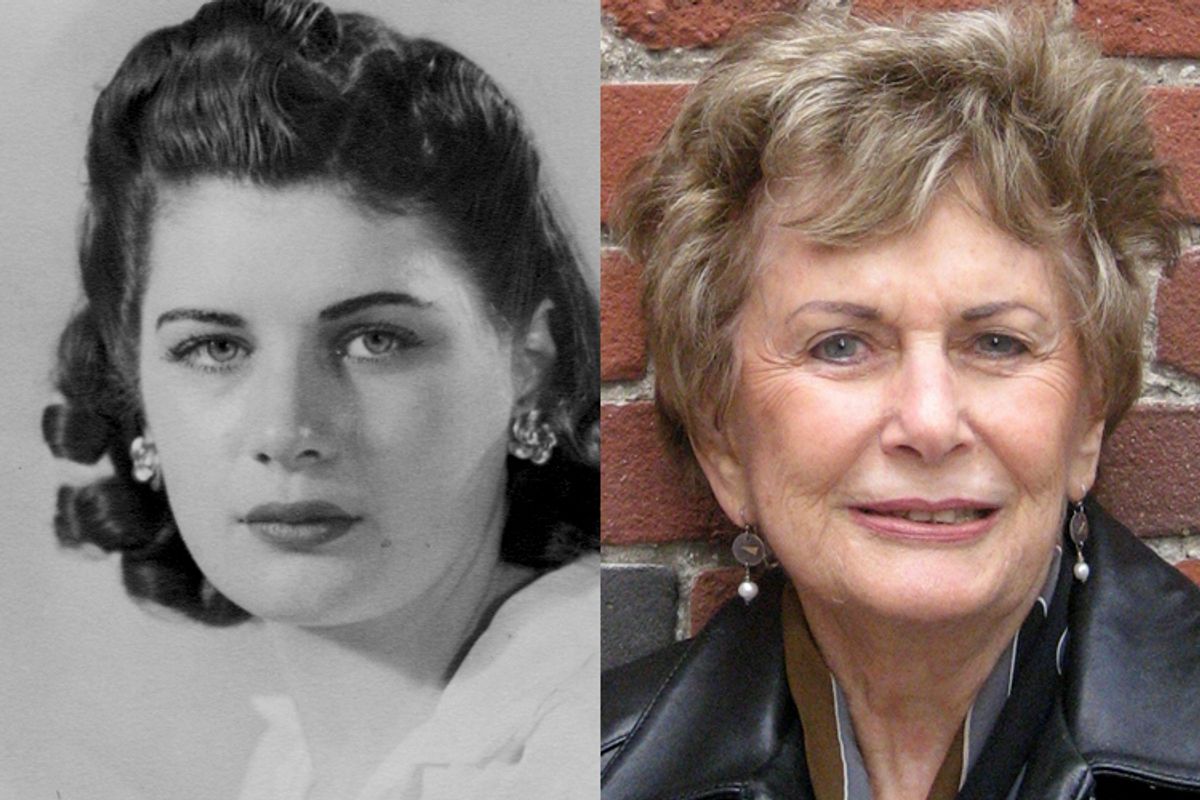

Surely no one can live in a society that instructs us so relentlessly about all the ways we can overcome aging, without wanting to do something about it. I know I can't. Why else do I go to the trouble and expense of dying away my gray hair when I hate to sit in the beauty shop? Why else does my heart swell with pleasure when someone responds with surprise when I say that I'm 87 years old? Why else do I know with such certainty that the minute they stop looking surprised is the minute I'll stop saying it.

As I read, listen, talk, write, it seems to me we're living in a weird combination of the public idealization of aging that lies alongside the devaluation of the old. And it isn't good for anybody. Not the 60-year-olds who know they can't do what they did at 40 but keep trying, not the 80-year-olds who, when their body and mind remind them that they're not 60, feel somehow inadequate, as if they've done something wrong, failed a test.

We live in the uncharted territory of a greatly expanded life span where, for the first time in history, if we retire at 65, we can expect to live somewhere between 15-20 years more. But the story of this new longevity is both positive and negative -- a story in which every "yes" is followed by a "but." Yes, the fact that we live longer, healthier lives, is something to celebrate. But it's not without its costs, both public and private. Yes, the definition of old has been pushed back. But no matter where we place it, our social attitudes and behavior meet our private angst about getting old, and the combination of the two all too often distorts our self-image and undermines our spirit.

Yet too few political figures, policy experts or media stories are asking the important questions: What are the real possibilities for our aging population now? How will we live them; what will we do with them? Who will we become? How will we see ourselves; how will we be seen? What will sustain us -- emotionally, economically, physically, spiritually? These, not just whether the old will break the Social Security bank or bankrupt Medicare, are the central questions about aging in our time.

Lillian B. Rubin is an internationally recognized author and social scientist who was, until recently, a practicing psychotherapist. Her most recent work is "60 on Up: The Truth About Aging in America." She lives in San Francisco.

Shares