"Question - Reponse" by Daniel Mar

At the New Yorker Book Bench Macy Halford recently posed an important question: "What is wanting to write without wanting to read like? It's imperative that we figure it out, because Giraldi's right: It's both crazy and prevalent among budding writers." She was echoing a question asked by debut novelist William Giraldi who in the course of teaching writing at Boston University has noticed a growing number of aspiring writers disinclined to read. This unfortunate trend inspired an open-ended analogy:

At the New Yorker Book Bench Macy Halford recently posed an important question: "What is wanting to write without wanting to read like? It's imperative that we figure it out, because Giraldi's right: It's both crazy and prevalent among budding writers." She was echoing a question asked by debut novelist William Giraldi who in the course of teaching writing at Boston University has noticed a growing number of aspiring writers disinclined to read. This unfortunate trend inspired an open-ended analogy:

Wanting to write without wanting to read is like wanting to ____ without wanting to ____.

The New Yorker commenterati -- unsurprisingly, a clever bunch -- came up with some great analogies but none of them touched on the bigger question: How can anyone claim to be interested in writing without being serious about reading? If Giraldi's observation rings true across teenagers and 20-somethings then what does this say about culture at large?

I have always loved to read. A day that permits me an hour of reading before having to get out of bed perks me up better than coffee. I also consider myself a writer. I've been kept awake at night thinking about and working on a story and found myself with finished pieces that I can't recall how they actually took shape; I've also struggled and felt like giving up. While the moments of magic happen, writing, for me, is hard work and at times incredibly frustrating.

Reading, on the other hand, is not a struggle. It is an utter pleasure. And it is in this pleasure where I first took up the challenge of writing, in trying to emulate the wordsmiths whose stories possessed me so completely that the rest of the world would fade away so long as I kept turning the pages and allowed their words to fuel my imagination. Whether I was tagging along on the adventures of the Three Investigators, tangled in a Mark Twain yarn, laughing at jokes that I didn't understand fully in old Doonesbury books or frightened by Stephen King (and mesmerized by his sex scenes), these experiences got me wanting to read more and more, from the high school literary canon to Grisham and Clancy thrillers.

As a kid I also wrote. Every week, my eighth grade English teacher Mr. Powell issued a word, like "twist," and the following week we would hand in a story built on the assigned word. I wrote about a kid at a party who twisted off one too many beer bottle caps and ended up wrecking a car. I certainly hadn't started drinking yet, but I'd read about it and clearly something had stuck enough to inform this story.

With age the trajectory of my reading habits drifted literary and I began copying Hunter S. Thompson's stylized disgust and Jack Kerouac's verve. I would write out their sentences and try to hit their strides with my own words. Obviously, plenty of young writers still do this, whether they fancy themselves the next F. Scott Fitzgerald or J.K. Rowling. But what do we make of those want-to-be writers that don't think it's important to read?

Books about writers trying to write have been around for a long time. Books about writers trying to write while also juggling their teachings gigs have also been around for a while. Nabokov did it quite well and was ahead of the curve. Michael Chabon gave us something entertaining with "Wonder Boys." But there has been an uptick in books with titles like "After the Workshop" and "All the Sad Young Literary Men." Scores of similarly themed books indicate a trend in contemporary publishing to reward writing about writing, or trying to write. Why? Because a great number of people who buy and read such books relate to the struggle and find solace or perhaps even redemption in these tales. It is what they know; the territory is familiar, to the point that some of these readers might say to themselves, "If this guy can do it, so can I!"

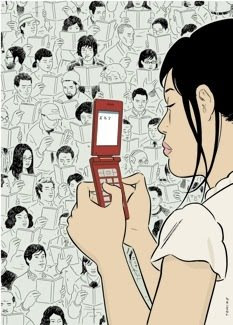

Adrian Tomine via The2Moons

On a much larger scale, this is the same mentality that drives the Japanese "mobile phone novel" phenomenon, keitai shoushetsu. All the rage in Japan and China, stories and books written via cellphones are huge business, according to Wired UK: "The largest mobile phone novel site, Maho i-Land, features more than a million titles and is visited 3.5 billion times each month. In 2007, five out of the 10 best selling novels in Japan were originally mobile phone novels." This popularity has spurred Movellas, a Dutch company, to set up a similar model in Europe with its eyes on English-speaking markets. CEO Joram Felbert equates the books to diary entries.

Apparently, the journaling quality of these works lends itself to Justin Bieber fan fiction laced with text-message acronyms. Notions of "craft" are not a real issue for these authors. But let there be no doubt, if these are the sorts of books publishers can sell, then these are the books the publishers will champion. It follows, that in the same way certain fiction writers recognize aspects of themselves in books about writing fiction and propagate more of it, fans of social networking fiction will see themselves in it and continue this new tradition. Driven by sales, it will become popular and the thought of reading the canon, or even Danielle Steel, will be considered tedious and unnecessary.

There is also something to this growing disconnect between writing and reading that Steve Himmer touched on in his excellent piece that appeared at The Millions: "Yet I can't help but remember that reading -- both the careful selection of books and being given enough privacy to quietly read them myself -- was among the first freedoms I had." Humanity is losing its ability to be alone with nothing but our thoughts. Both writing and reading are solitary acts. They are also liberating acts that can free practitioners of either from reality for as long as someone chooses to read or write. You fall into the moment of the act, commit yourself to it, indulge imagination to the point that it usurps the daily grind -- the tedium of work, relationship troubles, baleful news reports -- and you the reader, you the writer, are all that exist as a sounding board for the words, no matter what their story.

The pervasiveness of social networking corrodes the ability of words to bestow the enchantment of solitude. Being alone is not so much considered a freedom or luxury anymore, especially among teenagers. It's a punishment. Behind closed doors, away from nosey parents and annoying siblings, the connection to friends and the details and distractions of life stream through walls and windows, eradicate distance.

In fact, the channeling of experience through Facebook and Twitter as it happens, and seemingly before a moment is even allowed to pass fully, undercuts one of the traditional tenets of reading and writing: metaphor. In our age of immediacy, the associative distances that shape shift with the diversity of snowflakes are endangered. In the same way that Susan Sontag recognized how photography became the standard of visual beauty, trumping the figures and objects in the photographs, the diminishing of distance has irrevocably changed our sense of how we describe the world we inhabit. Immediacy kills metaphor and its demise unquestionably plays a role in perspectives on craft. Or maybe the bolder point is that craft is of little interest to certain want-to-be writers. In our 15-megabytes of fame culture that favors quantities -- friends, followers, number of comments -- over quality this might be what it all comes down to, because if you can be recognized and rewarded as a writer without being much of a reader, guess what, most people will not try to read James Joyce.

Growing up poor in Harlem, James Baldwin found in his local library the answers to questions he otherwise never would have thought to ask. As his biographer W.J. Weatherby describes it: "It was reading that saved him. It was an escape from his stepfather, his home life, the Harlem streets, the other boys, the cops. A book could take him far away." In Baldwin's words: "I read books like they were some weird kind of food." Feasting on stories that on the surface in no way related to the life he lived on a daily basis taught Baldwin how to peel away surface levels and find the less obvious commonalities. Baldwin's reading habit not only gave him the tools with which he built a tremendous career as a writer; it saved his life because reading also taught him how to be alone with himself, even if at times that solitude was discomforting.

"The New Novel" by Winslow Homer via Wikipedia

Yes, ambitious, talented writers will continue to exist and their writing will be great because they have read. And yes, there will remain people who have nary an interest in writing but luxuriate in an afternoon of reading. The devaluing of imagination as it departs on flights of fancy brought on by just being with yourself, this is what is changing us in profound, yet to be fully realized ways.

Wanting to write without wanting to read is like wanting to use your imagination without wanting to know how.

Copyright F+W Media Inc. 2011.

Salon is proud to feature content from Imprint, the fastest-growing design community on the web. Brought to you by Print magazine, America's oldest and most trusted design voice, Imprint features some of the biggest names in the industry covering visual culture from every angle. Imprint advances and expands the design conversation, providing fresh daily content to the community (and now to salon.com!), sparking conversation, competition, criticism, and passion among its members.

Shares