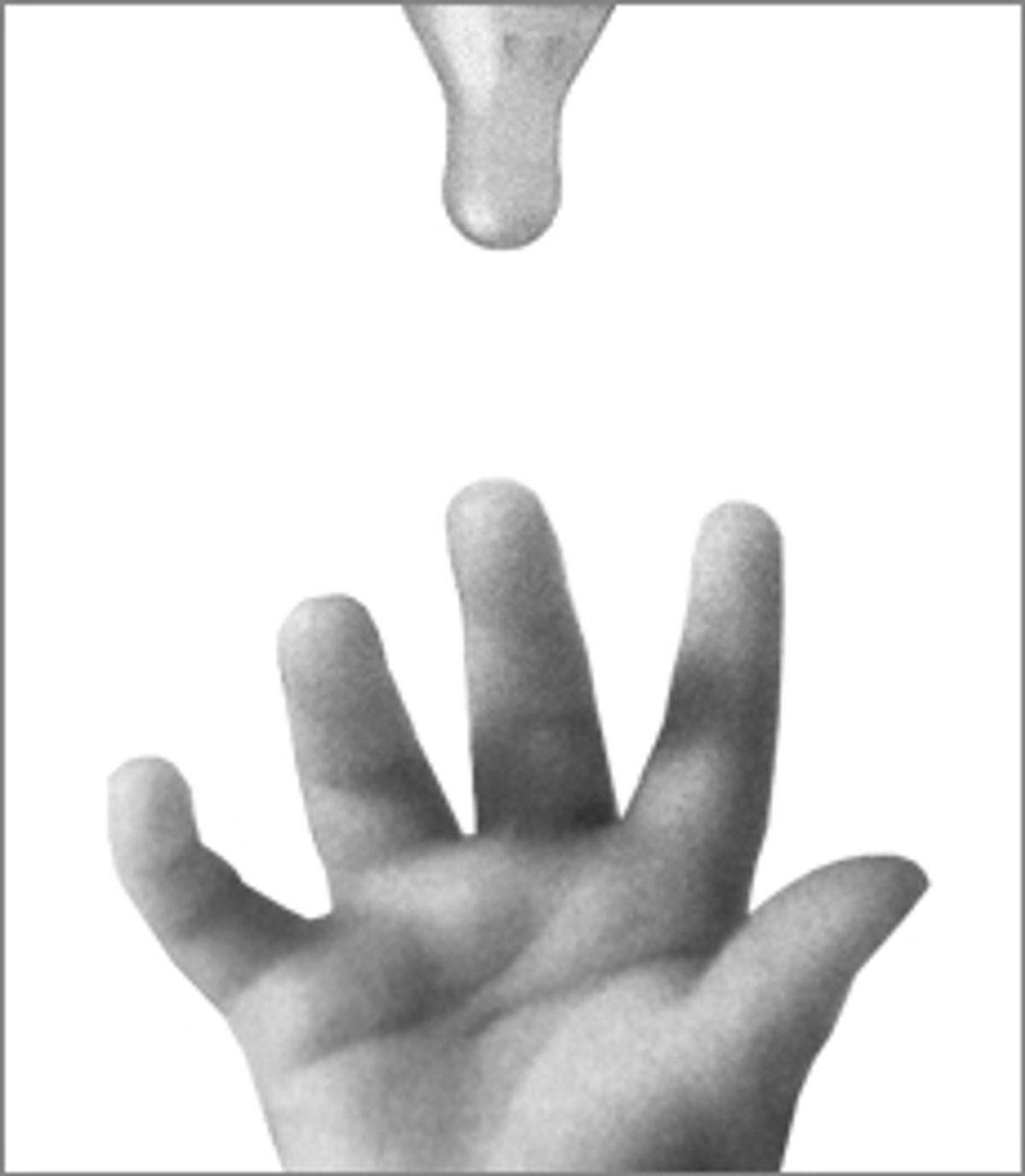

Several times a day during the first seven months of my son's life, I retreated to my bedroom, placed suction cups over my breasts, flipped the switch of an industrial-strength breast pump, and watched as drops of milk collected into the two plastic bottles I held in my hands. During my pregnancy, I'd had every intention of breast-feeding; I'd even looked forward to it, imagining my infant and me pressed against each other in a rocking chair, in Mary Cassatt-style bliss.

But my baby never figured out how to latch on without causing me excruciating pain -- I'll spare you the bloody (literally) details but let's just say there were days when the act of putting on a bra left me in tears. I spent more than $1,000 on home visits from four different lactation specialists, and read every book and Web site about breast-feeding I could find. But no pillow, position or dietary adjustment helped. And so I logged many uncomfortable and lonely hours at the pump.

Why did I stick with pumping for so long -- an activity that took me away from my son for as long as 30 minutes five times a day -- when I could have bought a case of formula and been done with it? In a word: guilt. Every time I thought about quitting, I heard the mantra that had been drilled into my head by books, doctors, nurses, friends and even strangers -- breast is best.

Now, the federal government is getting into the guilt game. According to an article in Tuesday's New York Times under the headline "Breast-Feed or Else," the Department of Health and Human Services is sponsoring a public health campaign designed to inform the nation's new mothers not only that breast-feeding is best but that failing to do so could actually harm their babies. One television ad mentioned in the Times shows a pregnant woman clutching her belly as she is thrown off a mechanical bull, as the voice-over intones: "You wouldn't take risks before your baby's born. Why start after?"

It's hard to imagine a more guilt-inducing message. (Except maybe for the one tossed out by Suzanne Haynes, senior scientific advisor to HHS's Office on Women's Health, who told the Times, "Just like it's risky to smoke during pregnancy, it's risky not to breast-feed after.") I'm not arguing against breast-feeding itself. Taking the Times piece at face value, there is strong evidence that breast-feeding is indeed the best way to feed infants. Among many other benefits, breast milk protects against infections and has been linked to a decreased risk of SIDS, diabetes, leukemia and maybe even childhood obesity. (Though the studies on obesity and breast-feeding mentioned in the Times didn't control for affluence of the mother and other lifestyle factors, which makes you wonder if other breast-feeding studies have been similarly imperfect.)

Yes, it would be great if more women breast-fed their babies. And I guess it's nice that the government is reminding women of the benefits of breast milk. But in their heavy-handed, bullying approach, these ads are like the lactation equivalent of the this-is-your-brain-on-drugs ads of the 1980s. The difference is that nobody has to smoke dope, but many women do have to work. The campaign willfully ignores the reality of most women's lives. The fact is, real barriers, both physical and financial, stand between many mothers and breast-feeding -- a fact the Times quickly glided over. Not one breast-feeding proponent interviewed, for example, was asked to explain how the more than 60 percent of mothers of young children who work are supposed to exclusively breast-feed for the recommended six months. Nor did they comment on the fact that even if a woman is fortunate enough to afford to take the 12 unpaid weeks of leave mandated by the Family and Medical Leave Act, she still will fall short. No experts were asked about the role of race and class in breast-feeding, even though the Times article noted that black women are less likely to breast-feed and that the rate of breast-feeding increases with education, income and age -- presumably because those are the women who have the resources and support to do it.

It's really infuriating. The same government that's warning women that they're risking their children's lives if they don't breast-feed makes it almost impossible to do so by not providing them with mandatory paid maternity leave. The Times interviewed one mother who characterized breast-feeding as a "lifestyle" and admitted that her life "revolves around my kids, basically." But few women have the option to make that kind of lifestyle choice, no matter how much they might want to.

And those were the voices that were missing from the article -- and, frankly, from the larger cultural debate about breast-feeding. One mother I know ended up in the hospital for a week with a terrible case of mastitis and was forbidden to nurse when she was discharged. Another friend had a premature birth and while she pumped some milk for her son, she had to also give him formula. Like all mothers, these women wanted to do right by their babies and were well aware that breast milk is "the gold standard," as the HHS's Haynes calls it. But they physically couldn't do it. Did they really endanger their kids' lives? Of course not. Millions of healthy people were given formula as babies. It might not be optimal, but it's not poison.

But what if the Just Say Yes breast-feeding campaign has reached a significant number of women who otherwise wouldn't have known about the benefits of breast-feeding? Would the scare tactics be worth it? Are the outrage and guilt of people like me, people who are aware of the benefits of breast-feeding already, a fair price to pay for the increased health of thousands of infants? After all, my son benefited from my overwhelming guilt. Then again, I was miserable for the first few months of his life.

The fact is, breast-feeding in the industrialized world is a lot more complicated than the ads make it appear, and it would be nice if the government and breast-feeding advocates acknowledged that. Maybe they could come up with an ad campaign against employers who have the gall not to offer paid maternity leave. They could feature people in suits riding mechanical bulls while balancing babies on their laps with the tagline "You wouldn't put your employees' babies at risk before they were born. Why start after?" How does that sound?

Shares