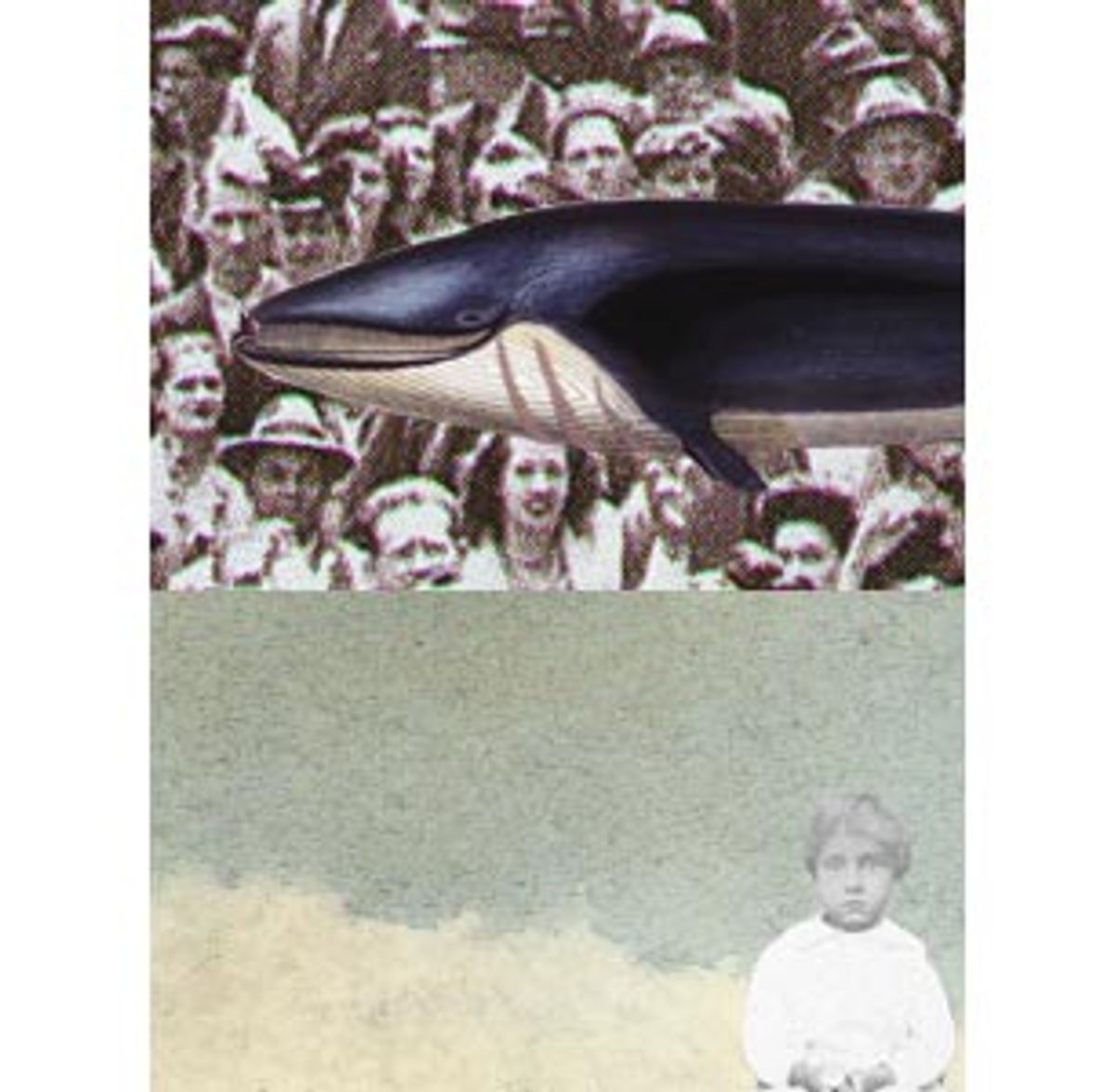

Last night, I watched "Wild Rescues" on Animal Planet TV. A family of four pilot whales had beached themselves off the coast of Florida, and 100 people a day volunteered to stand in waist-deep water to hold the enormous mammals up off the ocean floor so they could heal, so they wouldn't lie down in the mud and suffocate. They did it for weeks, until the whales were able to survive on their own.

Two weeks ago, 6-year-old Kayla Rolland was shot and killed by a first-grade classmate. The child who fired the gun found it at "home," which happened to be a crack house where a second gun and drugs were found. The boy lived there with an uncle who was supposed to be caring for the child after the boy's father went to jail and his mother was evicted.

Immediately after the killing, there were some perfunctory expressions of pity and a resurrection, now almost reflexive, of the gun debate: Kids shouldn't have them; guns should have safety latches; schools should have metal detectors even for kids who are 6 years old.

But where were the 100 volunteers -- before or after the tragedy? Where were the people who recognized this boy's misery, who would hold him so that he might heal, so that he wouldn't suffocate from neglect?

Amazingly, there has been very little public outrage about the child neglect in this story, other than a finger-wagging condemnation of the boy's parents and uncle for allowing him access to guns and drugs. And that is frightening, because this is a story about neglect. The gun is merely a prop, an attention-grabbing finale to an epic tale of mistreatment and pain.

The easy response, the knee-jerk reaction that temporarily quiets that nagging feeling that the world is intrinsically unsafe for our children, is to assign blame. We can point at those bad parents, who obviously screwed up, and then feel good, because we are better parents. We do not allow our children to roam free in a crack house in a bad neighborhood.

The distance we put between ourselves and those people is created out of a lie that prevents us from getting angry enough to do anything about child neglect and abuse. We can dismiss the abusers as criminals, and we might even convince ourselves that there's nothing we can do to keep them from hurting their children.

But we can't escape the fact that the way their children are raised affects our children, too. If we understand that rescuing pilot whales is, ultimately, an act of self-preservation, why can't we make the connection with our own species?

We are letting abuse happen. Children are abused and neglected because we are unwilling to spend the money on programs to prevent it, and because we look away when we see a kid who is hostile and violent or extremely withdrawn -- two classic signs of a kid who is being hurt.

We are surprised and horrified when we hear about the worst cases: the child locked in one room for several years, the father who poured gasoline on his daughter and set her afire in the desert. But it's hard to conceive of how this applies to us, until something like the Michigan shooting grabs the headlines.

I am amazed and I am devastated by what people don't know, or don't want to know, about child abuse. Around 1 million children are known to be abused or neglected in this country each year. Yet people are shocked when I tell them the things I see as a child advocate: broken bones, fractured skulls, cigarette burns, belt marks across a 4-year-old's face, sexual abuse of a 3-year-old, a 1-year-old in a coma because of abuse.

As I confront these things, it's not the physical injuries that startle me; it's the look in these battered children's eyes. They don't want to look at me; they don't want to trust me, or any adult. They don't see the world as safe or peaceful or interesting. They see it as terrifying.

And I see it as terrifying, too, because there are so few people invested in ending child abuse and helping to heal the victims. We criticize Child Protective Services for not investigating reports or for dropping the ball, but every year in state legislatures across the country, child advocates struggle to get funding for more and better-trained CPS workers -- and fail. There are not enough foster families, social workers and volunteers to work with these children because it's a tough job and dollars are scarce. We have not made this a national priority.

And while these needs are monumental, they still address child abuse and neglect only after it happens. Even if we could drum up money for more and better people to identify and address the effects of child abuse, it would do little for prevention. We need to find out why it happens -- a bigger question with a much more complex answer.

Poverty, youth and lack of education are big factors in abuse and neglect, as are drug abuse, parents who were victims themselves and those moments of insanity and rage that every parent feels from time to time. None of these are issues that can't be addressed through better emotional, educational and financial support of parents and children. Parents need help in dealing with whatever demons are plaguing them. By helping them, we spare their children.

In every case I've seen, a little help in just one area probably would have made the difference. In Michigan, this little boy's mother was evicted and his dad was in jail, which meant the kids went to live with their uncle in a crack house. I wonder what would have happened if someone (the landlord, a neighbor, a friend) had looked into where the mom would go after being evicted and what was going to happen to the kids.

Where is our passion for other human beings? Why does it seem easier to lavish it on pilot whales? We need to identify with the parents who hurt, or might hurt, their children. We need to find the courage to say, "What do you need? I'll hold some of the crap you're carrying so it doesn't get too heavy for you."

When we see a kid who's being a pain in the ass, like the boy in Michigan apparently was, or who is too quiet and afraid, we need to stop thinking that it's none of our business; we need to stop dismissing the kid as a brat or a freak, and find out what's going on.

The Michigan shooting is a perfect opportunity for some good old-fashioned public fury and some private transformation. We need to confront the ugly reality of neglect and feel an urgency to address it, because it affects all of us. And then we have to make protecting children the most important thing we do.

We need to believe that all families are connected, and that we have a responsibility to other parents to be aggressive in reaching out to them when they need help, in making sure the services they need are there and in helping them be good to their kids.

It is easier -- or at least no more demanding -- than standing waist-deep in water with your arms around a whale.

Shares