Elizabeth Harris still isn't sure why she did it.

She had filled her cart with $80 worth of groceries for herself and her 4-year-old son, and was standing in line waiting to pay for them. On impulse, she picked up a Bic lighter and slipped it into her pocket. In a lifetime that had already given her plenty to regret, Harris would come to regret this action more than any she had ever taken. It would trigger a chain of events that, three years later, has left her unlikely ever to see her child again.

It's worth mentioning that Harris, 39, is not simply a shoplifter; she is also a drug offender, with a lengthy history of using and selling methamphetamine. It's a history she says drew to a close within the last few years when, in fits and starts, she managed to get herself into a rehab program, secure permanent housing, stop using drugs and stabilize her life.

But Harris didn't do these things quickly or consistently enough; didn't do them on the timetable handed to her by the court that claimed jurisdiction over her son in the wake of her shoplifting arrest. As a result, like a growing number of women caught in the crushing nexus of the criminal justice and child welfare systems, she has seen her parental rights permanently terminated and her child placed for adoption.

In an election season that finds both major candidates throwing themselves at the feet of the sacrosanct "middle-class family," both have publicly ignored an aspect of national policy -- the ongoing drug war -- that has permanently destroyed thousands of families that don't fit the campaign ideal. This crusade, which escalated under the current administration, is unlikely to reverse course under the next, whoever wins the election. In fact, the drug war is succeeding where the culture wars of previous election cycles failed, in writing legions of "undesirable" American families out of existence entirely.

These families are dissolving under the pressure brought by a combination of laws and policies that can truly be called bipartisan achievements: a new emphasis in child welfare law on adoption and speedy termination of parental rights (a favorite policy of President Clinton's which George W. Bush has parroted so enthusiastically); mandatory sentences for drug offenders (a legacy of the Reagan/Bush Sr. years that the Clinton administration has made no effort to reverse); welfare reform (trumpeted by Al Gore in the first presidential debate as a heartwarming bipartisan success story); and a shift in enforcement of so-called "deadbeat dad" child support laws to target single, incarcerated mothers. The net result is that women who serve time on even relatively minor charges may find that the penalty for their crime includes forfeiture of their motherhood.

This loss is especially devastating for women struggling with drug involvement, say researchers and social workers, because when they lose the role of mother, they lose one of the most powerful motivations for recovery. For these women's children, who have a hard time understanding that their mothers have disappeared not by choice but by decree of the court, the legal termination of their relationships with their mothers is often experienced as profound, and confusing, abandonment.

The Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA), passed in 1997, has hit prisoners and ex-offenders particularly hard. ASFA mandates that the states begin proceedings to terminate parental rights once a child has been in foster care for 15 out of the past 22 months -- six months if the child is younger than 3 years old. The law also promises bonuses of up to $6,000 for each adoption over pre-ASFA levels.

Championed by Hillary Clinton and popular with child welfare advocates, ASFA was written to address the needs of children who spend years or decades bouncing from one foster home to another while their parents blow chance after chance to get their lives together. But, as with any pendulum swing, ASFA has had some extreme consequences, sweeping many parents into its net before they have had a fair shot at preserving family bonds.

Both adoptions and terminations of parental rights are rapidly increasing across the country. There were 46,000 children adopted out of foster care in 1999, up from 28,000 in 1996; and the number of additional children whose parents' rights had been terminated and who were "waiting for adoption" grew from 37,000 in March of 1998 to 46,000 in September of 1999.

Meanwhile, as a result of the drug war, women have become the fastest-growing segment of the prison population. The number of women in state and federal prisons has increased fivefold in the last three decades, to 84,400 at the end of 1998, and the tide shows no sign of slowing, much less turning. Eighty percent of incarcerated women are mothers, and because most women prisoners are single mothers, their children are particularly vulnerable in their absence.

Across the country, those who work with incarcerated women say they have seen a particularly steep increase in terminations of parental rights among prisoners -- an increase which, as stepped-up enforcement of ASFA collides with the ever-larger numbers of women pouring into prison, many expect will turn into a flood.

Philip Genty, clinical professor of law and director of the Prisoners and Families Clinic at Columbia University Law School, sees more than 150 prisoners a year in New York-area facilities (where he and his students lead family law workshops) and has written widely on termination of parental rights. Prisoners facing termination proceedings were once the exception, says Genty; now, among those whose children are in foster care, they have become the rule.

"It is a very rare situation where a woman prisoner with a child in foster care has not been confronted with this," Genty says.

The reason for this lies in simple arithmetic: Long sentences for drug offenses leave many prisoners doing stints for even minor infractions that exceed ASFA's six- and 15-month time limits. In New York, 91 percent of women convicted of felonies, including low-level nonviolent crimes, will serve at least 18 months -- three months more than the longest ASFA time limit. Social services departments, Genty explains, "feel that ASFA puts pressure on them to move children out of the system quickly even when they think there may be a decent relationship between parent and child. They don't have the ability to wait for the parent to get out of prison."

Marilyn Montenegro, prison project coordinator of the California chapter of the National Association of Social Workers, says many social workers are themselves "very frustrated" by the constraints under which they are forced to operate. Most social workers, says Montenegro, believe that ongoing contact with biological parents is "almost always in the best interests of the child," but the law does not create a means to facilitate that contact if parental rights must be terminated by a particular date. "They [social workers] say, 'My hands are tied. There's nothing I can do,'" says Montenegro.

The laws passed to implement ASFA vary from state to state. New York passed a relatively mild version last February that did not change any of the grounds for termination of rights but did, as required, incorporate the new federal timetables. According to Genty, at least half the remaining states now have legislation on the books that makes specific reference to incarceration as a factor in or grounds for termination; in these states, it is safe to assume that the number of prisoners who lose their parental rights would be even higher than in New York.

Illinois, for example, has passed a particularly harsh ASFA law, adding several new grounds for termination that specifically target incarcerated parents. Under a "three strikes"-style provision of the Illinois law, any parent with a child in foster care who has three felonies with one in the past year (including possession, writing a bad check or shoplifting, if they are charged as felonies) is presumed "unfit" and is subject to termination proceedings. The same goes for parents who will be incarcerated for the next two years, or who have already been locked up repeatedly. The result, says Joanne Archibald, advocacy director for Chicago Legal Aid to Incarcerated Mothers, is that "more and more women are losing their kids."

Attorney Lynn Vogelstein, currently a fellow at the Institute for Children, Families and the Law at New York University's School of Law, worked until recently with South Brooklyn Legal Services, which represents former prisoners in family court. Among New York's incarcerated mothers, she says, the typical scenario involves a woman who hits the 15-month time limit while behind bars and find her rights terminated on the grounds of "permanent neglect and abandonment," defined under New York law as having had no contact with the child during the past six months.

Sometimes, says Vogelstein, women whose children are in foster care do not inform the caseworker when they are arrested because they believe to do so would make their situation worse. They don't realize that their silence can be construed as "abandonment." Other women, Vogelstein says, find their rights terminated for "failure to plan" for the child's future needs, despite the fact, she notes, "that it's very hard from jail to plan for the return of your child."

The result, says Genty, is that "the mood in prison is one of despair. Essentially, what incarcerated parents are being told is that no matter what they do, how hard they work at overcoming the issues that put their children in foster care and brought them to prison, they cannot avoid having their parental rights terminated."

Even those inmates who manage to get out of prison with a little sand left in the hourglass face a daunting obstacle course if their children are in foster care. First, the social services department gives them a reunification plan that might require, for example, that they complete a drug treatment program, attend a parenting class and provide a stable residence for their children. Since anyone with a felony drug conviction is ineligible for benefits, including housing, under welfare reform laws in many states, this last stipulation may prove particularly challenging. A criminal record also makes finding a job difficult, so market-rate housing is likely out of the question.

Former prisoners who do manage to obtain legal work may find their wages garnished by as much as half under child support enforcement laws. Designated "non-custodial parents" during their time behind bars, prisoners can be held liable for welfare or foster care payments received in their children's name during their absence. With interest and penalties for nonpayment, prisoners with several children may wind up with bills in the tens of thousands of dollars.

Residential drug treatment may look like the only answer, but budget cuts have left many programs with long waiting lists -- longer than the time allotted to fulfill the requirements for reunification. The net result is that many former prisoners fail to meet these requirements and termination proceedings begin.

The women most affected by these laws and policies are not generally model citizens. They have hurt their children through their involvement with drugs or through their involvement with boyfriends or husbands with ties to drugs. The question is whether the current cure -- lengthy incarceration, minimal treatment and, increasingly, the permanent severance of family bonds -- is worse than the disease.

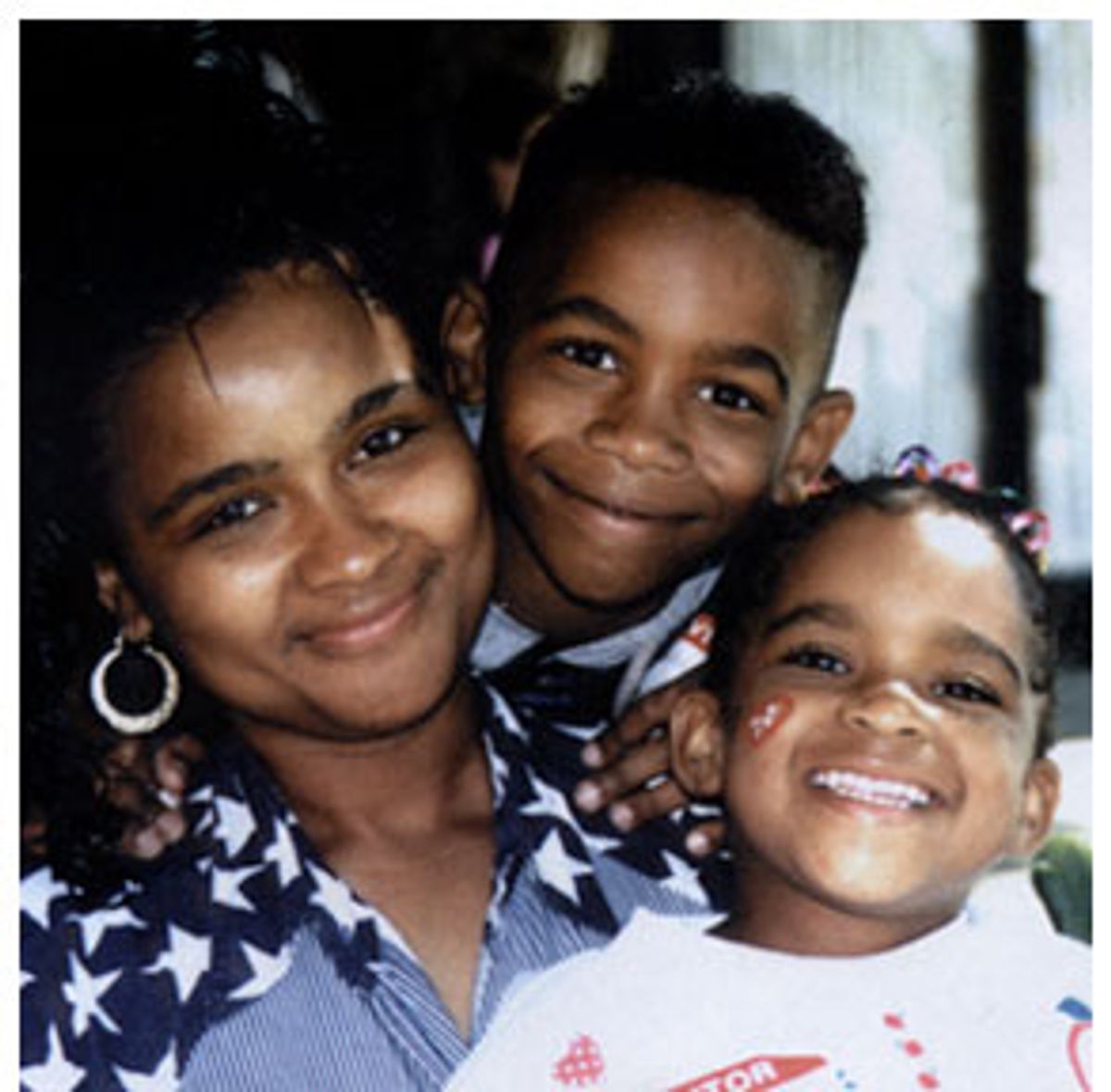

Elizabeth Harris is still trying to absorb the judge's decree, handed down a year ago, that she is no longer mother to her now 7-year-old son Anthony.

"It's a nightmare going through my head over and over," Harris says. "In the last two years, I have turned my whole life around. I haven't had any police contact, I have a car, a job, I maintain my home. My life has been good from when I started my [rehab] program, but as far as the system is concerned, it was too little, too late."

Harris' "nightmare" began two days after her release from jail following her shoplifting arrest. She had spent 30 days behind bars, during which time her sister cared for her son. The day after her release, Harris did not make it to a drug rehab program where her sister had secured a bed for her because, she says, she had to obtain a public defender and show up for a court hearing that day. She failed, however, to communicate these details to her sister, who assumed Harris simply hadn't bothered to show up and responded by delivering Anthony to the local police station and declaring him "abandoned" rather than returning him to Harris. Unable to locate Harris, who lived in a different county than her sister, the police handed Anthony over to social services, which obtained jurisdiction over him and placed him back with Harris' sister, then in foster homes.

In the months that followed, Harris became deeply embroiled with the Department of Social Services and the court. She was given a reunification plan that required her to enter drug treatment, secure housing, attend a parenting class and get therapy. Harris says that the drug treatment programs she contacted either had long waiting lists or couldn't reach her when they did have an opening because she was homeless (finding housing was virtually impossible in a market where prices had gone through the roof). Once she managed to secure therapy the department would no longer pay for it because her reunification services had been cut off. Armed with evidence of Harris' failures, the court terminated her parental rights and Anthony was placed for adoption.

Harris feels that when she turned to social services for help, she came up against an impenetrable bureaucracy that failed to adequately communicate its requirements, then penalized her when she could not meet them. The department maintains (in reports her social worker submitted to the court) that Harris continued to live a life of instability and probable drug use despite the fact that she had been offered both help and a clear warning of what would happen if she did not change her ways.

This kind of perception gap, says attorney Vogelstein, is not uncommon. Often, she says, caseworkers first meet a client at her very lowest point, so they may not be receptive to evidence of transformation. By the time Vogelstein meets them, often months later, "a lot of my clients are doing great things, but have been unable to communicate that to the agency."

Even when social workers are aware of the obstacles their clients face in meeting the criteria for reunification, they often find themselves caught between the requirements of the law and the realities of limited resources. "The social workers' charge is to act in the best interest of the child," says Marilyn Montenegro, "but they're really not given enough tools to do that very well. There isn't anywhere people can go where there's a nice place to live that's affordable. None of the people in the system have the ability to create that, so they're all stuck with the same old thing."

Harris doesn't claim to have been an ideal mother. "Part of the problem with substance abuse is you don't think you're doing anything wrong," she explains. It was only once she got into a rehab program that she realized the parenting standards she had set for herself were far too low. "I thought I was doing a good job by just providing a roof over the head, paying the utilities," she says. "But I wasn't there mentally and emotionally, putting his needs first."

Harris has even come to understand her sister's decision to turn Anthony over to the police. "She knew it wasn't fair the way I was raising him," Harris says. "And I know she meant it in my best interest for somebody to intervene. Somebody had to do it. She just didn't know the system -- the way it worked."

When the courts first removed Anthony from her care in the wake of her arrest, Harris says, "I had nowhere to stay and was still using drugs. It's hard for someone who's never been in that situation to even imagine what a person goes through. And then to give you a certain amount of time to either clean your shit up or it's over -- I don't think there's any time frame you can put on a person."

Ida McCray-Robinson, the family services coordinator at the county jail in San Francisco, spends her days organizing parenting classes, communicating with social services departments and talking with prisoners about their kids. Her evenings and weekends are consumed by the same labor; McCray founded the nonprofit Families With a Future, which facilitates contact between prisoners and their children at various state and local facilities, and runs it in her spare time.

"Half the women in here have lost children," says McCray-Robinson, 49, standing outside a women's unit at the San Francisco County Jail. And it's not just happening to women with lengthy sentences, adds McCray-Robinson.

"Momentary arrests, where she's out in two days, mean a woman could lose her kids. She gets arrested for petty theft, or whatever. There's nobody to take the kids. Child Protective Services gets involved. They take the kids to the nearest emergency shelter. Now they've opened a case. When that person gets out in two days or two weeks, she can't meet the requirements to get her kids back. And if that baby is under 3 years old, they've got their eyes on that baby, big time, because of the adoptability factor."

For many women, this is the point at which despair kicks in -- at their own failures, their children's resultant suffering and the seeming omnipotence of a bureaucracy that many find incomprehensible, if not hostile. They often treat this despair with methamphetamine, heroin, crack cocaine -- taking themselves one step further from the rehabilitation that is ostensibly the motive for incarcerating drug addicts.

According to Philip Genty, helping prisoners maintain family contact is one of the most effective means of achieving successful re-entry into society. When you eliminate that prospect, Genty says, "it removes one of the most effective tools towards rehabilitation."

That has been Lisa McDonald's experience. A crack cocaine and heroin addict, McDonald, 38, has been in and out of jail over the years; she is currently at San Francisco County Jail awaiting sentencing. Her last stint behind bars was four months for a probation violation. Her infant son was in foster care at the time and McDonald was released to a residential rehab program. Only when she called her social worker and asked for a visit with her son did she learn that her parental rights had been terminated while she was in custody.

Because she had not been notified of the hearing at which her rights were terminated, McDonald was granted another hearing after her release. By that time she was working at a center for the homeless, the first legal job she had ever held, and had completed a parenting program. Counselors from the rehab program accompanied her to the hearing, and she presented the judge with her parenting certificate. "Miss McDonald," she says the judge told her, "you've made a great improvement." But time had run out, and the termination was upheld.

"I felt like, 'What did I do all this for?'" McDonald says. "From that point on I degraded myself. The judge says 'no,' and it's like you are a bad person. That's the message I got, and in an unconscious way, I must have believed it, because after that, I wasn't really interested like I first was in my recovery. So nine months go by and I relapse, and that's how I end up back here." As a repeat offender, McDonald is now facing a possible three-year prison sentence.

Ida McCray-Robinson has experienced the rehabilitative power of family -- personally as well as professionally. She was 19 when she participated in an airplane hijacking orchestrated by a boyfriend. By the time she was arrested after 16 years on the run, McCray-Robinson had five children, who went to live with McCray-Robinson's mother and then with friends during their mother's 10-year stint behind bars. Staying in touch with her children, who visited regularly while she was incarcerated, "gave me a means and a reason to live and not be as awful as I could," McCray-Robinson says.

But her well-being was not the sole benefit of maintaining contact with her children, she adds. More important than her access to her children was her children's ability to have access to her, says McCray-Robinson. She and other social work academics believe that a child needs to have some contact with its parents, whether or not they are capable of providing for their needs at that time. Unfortunately, adoptive parents often don't provide children with regular access to their biological parents. There is no requirement that they do so, and many children adopted out of foster care lose touch with their biological parents (and their siblings) entirely.

"It doesn't matter whether you're a political prisoner, a robber or a dope fiend," McCray-Robinson asserts, "your children are mad and hurt if you're not there. An unspoken promise has been broken -- that they're going to have a mother to love them and take care of them.

"I hear people asking, 'How long should we wait until parents get it together?' I think there should be no limit (beyond which) there cannot be communication, except in cases of abuse. If somebody wants to be in touch with their parent, they should always have the right to know who they are and where they are."

But what about the argument that a child whose mother is likely to serve a long sentence deserves a permanent home, even if the price is loss of contact with that mother?

"I think you should ask my kids that," McCray-Robinson says.

McCray-Robinson's son Jundid was 3 years old when she was arrested and 13 when she was released. He now lives with his mother, his grandmother and several other family members on a quiet cul-de-sac in San Pablo, Calif. In the grassy front yard of his family home, a sprinkler arcs through the dusk as Jundid -- a soft-spoken 17-year-old in pigtails, a Reggae On the River T-shirt and gray sweats -- grapples with a question he did not have to face as a child.

Growing up without his mother in the house, Jundid says, was hard. "Everything that a person takes for granted, I missed so much. Whether it was cooking breakfast in the morning. Having a homemade sandwich instead of a bought lunch. Or just being able to say, 'Let me go home and ask my mom.'"

But Jundid is not convinced that severing his legal tie to his mother in the name of "permanency" would have healed these wounds. Visits with his mother, he says, anchored him throughout his childhood. "We made the most of each visit that we had. And my mom was very special about trying to give time to each child. Like for my sister, she would sit there and braid her hair while she had her little private time to talk to her. I remember she used to teach me karate. I'd show her my muscles, even though I didn't have any. But just me being relaxed and having fun with my mother is what I remember most.

"I couldn't even begin to express to you in words," he continues solemnly, "how fulfilling that was to my soul to give my mother a hug. For her to give me a kiss. For me to sit on her lap. And for me to not do that because of what someone else thinks -- I would have felt very empty then, as a child, and maybe as well now."

When his mother returned to his daily life after 10 years, Jundid says, the adjustment was difficult but also exhilarating. He recalls asking her to walk him to school, despite the fact that he was a teenager, to make up for an experience he had missed as a child.

"A lot of kids are ashamed that their moms are walking them to school," he says. "But I was so happy for her to be in my presence, and for the first time in my life to even come to my school, that I couldn't care less what people thought."

Through his ongoing contact with his mother throughout her 10-year incarceration, Jundid says, he learned something crucial about families: "When it's hard times, you stick together. And that was just a hard time."

Ellen Barry, founding director of San Francisco's Legal Services for Prisoners with Children, believes the kind of access Jundid had to his imprisoned mother is something all children deserve. "Kids own the right to have a relationship with their parents," Barry says, "even if they're not the best parents. The child has a right to be angry, to ask the parent to explain her behavior. That's his choice, not the society's choice. Society does have an obligation to keep children safe, but that's very different from terminating parental rights."

In fact, Barry points out, termination of parental rights is a concept most children can't begin to grasp. "It makes no sense to them that the court could come in and, with a wave of the hand, decide that the mother who gave birth to them is no longer their mother. Whether she's able to take care of them at this moment is a separate question."

Elizabeth Harris often wonders how Anthony understands her disappearance from his life. "He'd just turned four when all this happened," Harris says, "and what he understood as far as why he wasn't in mother's care was, 'Mom had a drug problem and she had no place for you to live.'

"So he always thought if Mom got a house and went to this (rehab) program, that he'd come back home. Now he's 7, and Mom did all these things, and he's still not home. You've got to wonder where his little mind takes him. He's still my child, and there's always gonna be that question in his mind: 'How come I'm not with Mama?'"

It's a question that has gone unasked and unanswered this election season, despite the hundreds of references to "family" sprinkled throughout the campaigns. Most prisoners and many convicted felons aren't allowed to vote, so they are, by definition, no one's constituency. Their children are equally disenfranchised, and even more rarely heard from. At a political level, these two groups are simply not needed, so the fact that they may need each other is easy enough to ignore.

But despite the silence at the federal level, elsewhere in the country a conversation is opening up on the staggering costs -- societal as well as economic -- of the drug war, and voters are, incrementally, being given the opportunity to consider alternatives. California voters, along with choosing a president this November, will also consider an initiative that would send nonviolent drug possession offenders and parole violators into treatment rather than jail or prison; a poll found support for the initiative at 55 percent. Arizona has already shifted to a treatment-based model, saving taxpayers an estimated two dollars for every dollar spent.

The war on drugs costs millions, fills prisons, and appears to do very little to stop people from using drugs. Compounded by severe social and child welfare policies, it is also decimating families across the country.

Children have long been used as a rhetorical weapon in this war, as in "We need to lock these people up before they get our kids hooked on crack." But "our kids" include prisoners' kids in ever-increasing numbers. What might it mean to them to have mom in treatment instead of behind bars; to know that she might ultimately recover from her addiction and be restored to them? The 10 million children who have seen a parent arrested and imprisoned offer the most compelling reason there is to open up the debate on treatment vs. incarceration and whether it is fair to punish parents (and children) by splitting them up -- permanently.

Shares