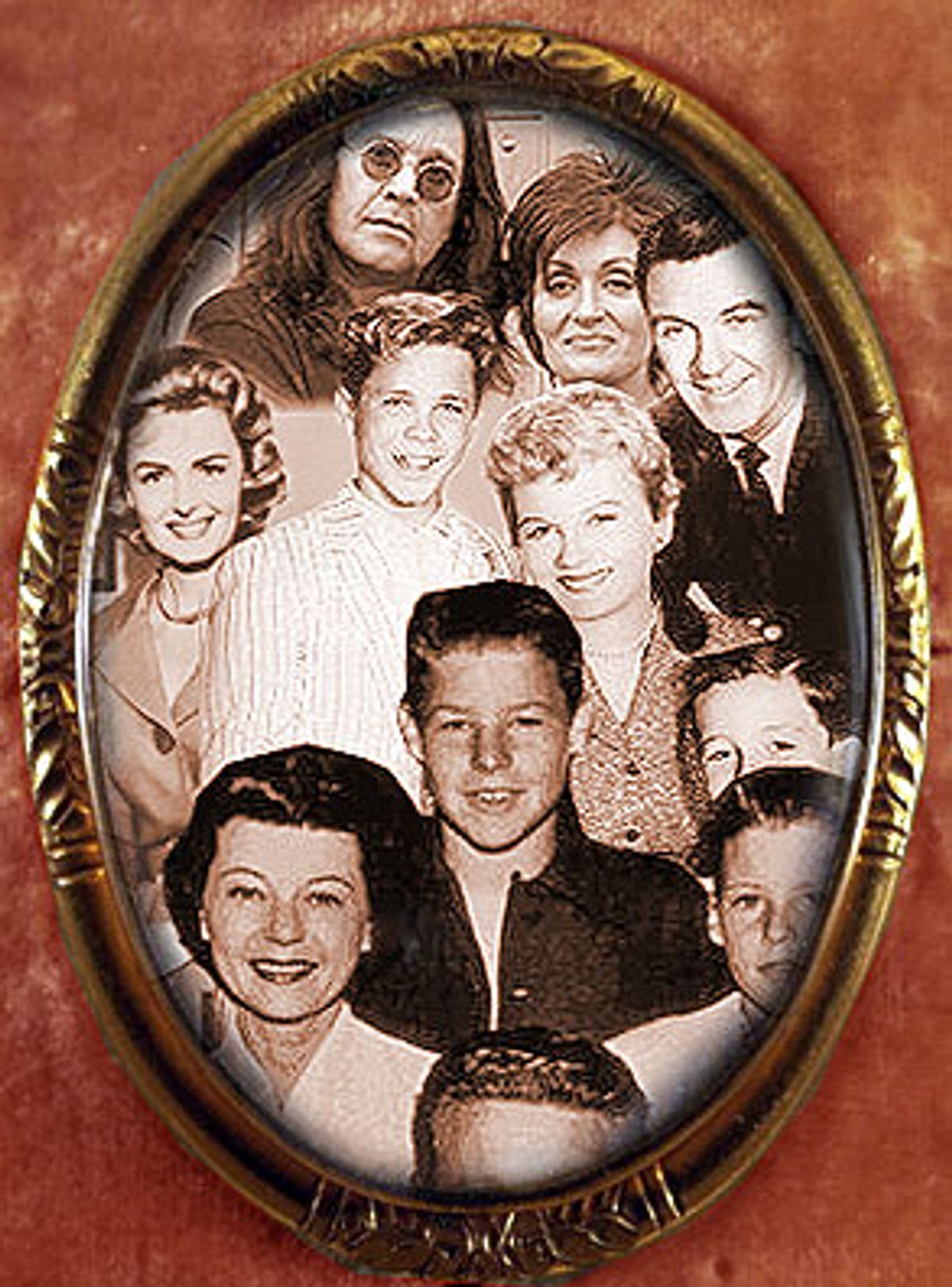

Once upon a time, the dysfunctional family was an aberration, an entity feared and shunned by normal families -- good families -- who modeled themselves on the Cleavers, the Nelsons, the Andersons and the Stones (as in Donna Reed, not Mick and Keith). The designation was uttered almost exclusively by experts in the dreaded "professional help" category. And such was the shame of dysfunction that the dysfunctional would go to extreme lengths to hide their flaws in function, believing an appearance of normalcy might actually move them closer to it, or at the very least make life easier for everyone, most of all the neighbors.

Which brings us, several decades later, to "The Osbournes," a TV family of daunting popularity that features drug-addled dinosaur rocker Ozzy Osbourne and his real-life wife, son and daughter. They go about their daily business before cameras, flipping each other off and peppering their conversations with the F-word. Much to the satisfaction of MTV, every obscenity, drug reference and unadorned outburst of intrafamilial angst brings more viewers, making the weekly Ozzyfest the second most popular show on cable (wrestling is first) and a favorite of President Bush.

Clearly, the dysfunctional family has been rehabilitated. What was once considered dark and unmentionable now constitutes high-quality entertainment. Profane kooks and apprentice psychopaths have become endearing TV stars, while televised confessions of supposed stigmas -- incest, drugs, alcohol, emotional abuse and relationships without civility -- have become a viable path to fame, wealth and warm societal acceptance.

"Lovable but dysfunctional families have been a trademark for Fox going back to the days of 'Married ... With Children,'" wrote Nellie Andreeva recently in the Hollywood Reporter. "The network hopes to keep that string alive." Indeed, Fox has at least five new shows in the works based on the dysfunctional-family premise, Andreeva reports. But the upstart network, which kicked things off with "Married ..." in 1987, now faces stiff competition.

And that's just what can be found in TV Guide. The dysfunctional family is a star of stage and screen, as well as a cavalcade of memoirs that take the very idea of a damaged family dynamic out of the shadow land it inhabited when it was mined only by a handful of high-culture writers such as Eugene O'Neill and Tennessee Williams, whose dysfunctional backgrounds served as source material, and into the down-market glare of the popular mass media. Most recently on the big screen, "The Royal Tenenbaums," a film about a tortured clan of social misfits, though not a blockbuster, has -- as of early April -- grossed nearly $52 million -- more than twice its production budget.

Meanwhile, intimate memoirs overflowing with kink and confession, such as Mary Karr's "Liar's Club" and its follow-up, "Cherry," as well as Kathryn Harrison's "The Kiss," have given amazing firepower to the literary market niche in recent years. Last and loudest, daytime TV shows such as those hosted by Jerry Springer, Jenny Jones and Sally Jesse Raphael have turned the most revealing personal confessions into a lucrative, if ethically questionable, entertainment product.

But then perhaps we never really understood the meaning of the word "dysfunctional" in the first place. Like a whole passel of other therapeutic terms, this is an adjective that seems to have slipped into the layman's language via the sloppy phenomenon known as psychobabble. Yet just as it is vague when used in everyday conversation, so does the "dysfunctional family" lack a precise definition even in the realm of psychology. The phrase encompasses a vast range of behaviors and can mean most anything the person using it wants it to, but a broad, generally accurate definition is: a family that functions poorly or not at all and communicates or behaves in ways that are emotionally unhealthy; a family that creates a negative environment that can be detrimental, or even catastrophic, to the development of its members.

Great, but what's a family? The nuclear family -- mom, dad, kids -- now constitutes a minority of the adult/child groups living together in the United States. So, not only has "dysfunctional" undergone an apparent transmogrification, the term "family" has outgrown its original meaning. At the same time that the emotional tangles of family life have begun to see the light of day, the nature of families has radically changed to include a growing cast of characters, making the entanglements more complex.

A brief history of semantics doesn't necessarily explain our fondness for families, whatever their composition, that are rife with "issues," as they are now called. But the morphing of the nuclear family surely has a role in the media celebration of messed-up domestic groups. If television means to offer a reflection of real life -- or, more recently, real life itself -- dysfunction is going to pop up, now perhaps more than ever. Beaver, Bud, Princess and Kitten -- every episode of their fictional lives involved a crisis, but it was a crisis fit for the times. Telling a fib was big news in the world of Ricky Nelson; it could be that Ozzy badgering his daughter Kelly about a gynecologist's appointment is the moral equivalent. What was dysfunctional in the old sense is still called dysfunctional, but these days it is also typical, much to everyone's relief.

Robert J. Thompson, founding director of the Center for the Study of Popular Television at Syracuse University, says that even what many consider the most dysfunctional TV families are "very functional at their roots." Of the three shows with the most beloved dysfunctional families -- "The Simpsons," "Roseanne" and "Married ... With Children" -- only the last had a family "that was really, truly dysfunctional," says Thompson.

"You could make the argument that all four of the people in that show would've been better off if they were not in that family," he says. "But in the case of 'Roseanne' and 'The Simpsons,' for all the trashy qualities on the surface, they are basically families that love each other, support each other, and all the rest of it, though not necessarily in traditional fashion."

(Thompson says he doesn't address the pioneering "All in the Family," which first aired in 1971, because the show featured no young children among the core performers.)

"'The Osbournes,'" Thompson adds, "proves that even a guy like Ozzy Osbourne, once best known for biting the head off a bat during a concert, has absorbed himself in what amounts to a bizarre, kooky and relatively foul-mouthed family, but it's a family nevertheless. People are together, they're coming home every night, it's completely functional. So, ironically enough, on one level pop-culture entertainment has really not let go of the notion of the ideal family."

In the venue of publishing, as in the realm of issue-obsessed daytime TV, where the raw confessional memoir -- on the page or in front of the camera -- dominates, the ideal family has been dismissed as myth. Nothing is forbidden, nothing is particularly embarrassing, all of it -- literate accounts of incest, shouting matches about paternity -- is aired ostensibly in the pursuit of mental health. And it may well be mentally healthy for the writer and the blurter as well as for their audiences. These are vehicles, Thompson says, "that introduce us to things going on with our fellow citizens that we may not be aware of."

Carl Pickhardt, a psychologist and novelist, calls the function of books like Karr's and Harrison's "a memoir catharsis." The writing has "allowed the expression of the dark side of family life to come to the surface," he says. "And I think that's good. It's also allowed some people to talk about and identify behavior that they previously took for granted and never thought had any particular formative effects."

In the process, Pickhardt says, "we've re-normed our view of family life. When we look at it now, we say that every family is a mix: The old notion of the idealized TV family isn't exactly true, but by the same token, the extraordinarily painful and traumatic vision given by a lot of these memoirs is not the whole story either."

Pickhardt, who has a private practice in Austin, Texas, thinks there's also been a shift in how therapists see troubled family relations -- and a change in their approach to helping. In the past, he says, "there was a view [on the part of therapists] of what wasn't there but should have been there, of negative things going on that were having destructive effects, and the power of the past. That needed to be investigated in order to help people heal from what had happened."

"That's still of therapeutic concern," Pickhardt adds, "but there's been somewhat of a shift so that now there's also an appreciation of taking a look at what is there, what is positively present, and focusing on what can be done in the present."

Therapists also tend to use the term 'dysfunctional' with much more restraint than civilians. "We describe families in terms of what their specific issues or problems are," says Dr. Leigh Leslie, a psychologist, family therapist and associate professor of family studies at the University of Maryland. "We have our diagnostic manuals. But [the language in them] is not what's common to the general public. That's not to say that professionals don't use the term, but when they do, they talk about what kind of dysfunctional family. It's not a term professionals use a lot."

Meanwhile, plain folks toss around the word with abandon. "Psychological terms are second nature to us because psychologists are part of our everyday dialogue," says Deborah Tannen, the author of "I Only Say This Because I Love You" and a professor of linguistics at Georgetown University. The down side of this trend, Tannen says, "is what I see as a tendency to pathologize. Sometimes we over-apply these psychological interpretations: We're calling people pathological when in fact they just have a different style.

"So, for example, the New Yorker who talks to the Californian is accused of being hostile when maybe she's just being blunt," Tannen continues. "Or you're accused of being pathologically secretive because you don't think it's right to talk about your personal life. You try to say what you want in an indirect way, you're called passive aggressive, you're called manipulative."

At first, some mental health professionals thought that incorporating psychological terms in common conversation was a good thing. "It showed some awareness," Leslie says. "But it does get to the point where now if someone tells me, 'I'm an enabler,' I have to ask, 'What do you mean by that?' Because it's come to mean so many different things, it loses its meaning for professionals. Psychological jargon has infiltrated our culture. I don't know that it always helps us communicate any better, but at least there's an openness to it."

There is no disputing the dysfunction and pathology of those who occupy the hot seats on the "Jerry Springer Show," "Jenny Jones Show" and others like them. They're programs, Thompson says, in which viewers see "the real nuts and bolts of family dysfunction ... you actually look into the heart of darkness of where a real American family can go, as opposed to a fictional one.

"What they've done," he says, "are two things: one very healthy, one perverse. The healthy part is what has brought a lot of this stuff out of the closet. That's a good thing -- they've taken the taboo out of speaking about this."

But the unhealthy part, Thompson says, "is that in packaging dysfunction as a form of entertainment it's become the only way in which a lot of people could ever achieve celebrity. By simply confessing, letting go, and paying the price of your self-respect and privacy, one is able to instantly get this kind of recognition that, of course, human beings long for."

This is, in Thompson's words "a little bit sick." But more important, it takes the confessional catharsis beyond the constructive point, when it demonstrates that we all have similar problems, to a place in which dysfunction becomes a badge of legitimacy. Suddenly, the most messed-up person wins the prize. Dysfunction, says Thompson, "turns out to be something that is valued in its own right as a means to keep the Springer show and the Jenny Jones show going. And that's the disturbing part."

Says Tannen, "People watch the Jerry Springer show and think, 'Those people are really sick. I can't believe they're on TV.' It's very different from what Oprah did, which in my mind was the opposite thing -- creating a sense of connection: 'Oh, there's someone talking about her problem. I had the same problem and I thought I was the only one. This is such a load off my mind. I'm not the only one.'" Jerry Springer, she says, "breaks that connection."

By the same token, though, shows like Springer's offer more selfish relief. The viewer might say, "I am so glad I don't have that problem. I'm better off than I thought I was." At that point, "dysfunctional family" reverts to its old definition, reserved for the truly hopeless and lost. Judging from the popularity of the Springer-like shows, that meaning maintains its charm as a nifty means of establishing superiority.

"People who use the term 'dysfunctional family' have no idea what they're talking about," Leslie says. "They know what their definition is, but is it a shared definition? Well, there is no shared definition other than it's a family that is having, or has had, some kind of severe problems.

"What people have become aware of is this notion that all families have problems, that it's normal to have problems, and the problem-free ideal family doesn't exist," she continues. "Terms like 'dysfunctional family' are not at all helpful to anybody, because it describes nothing and everything."

Shares