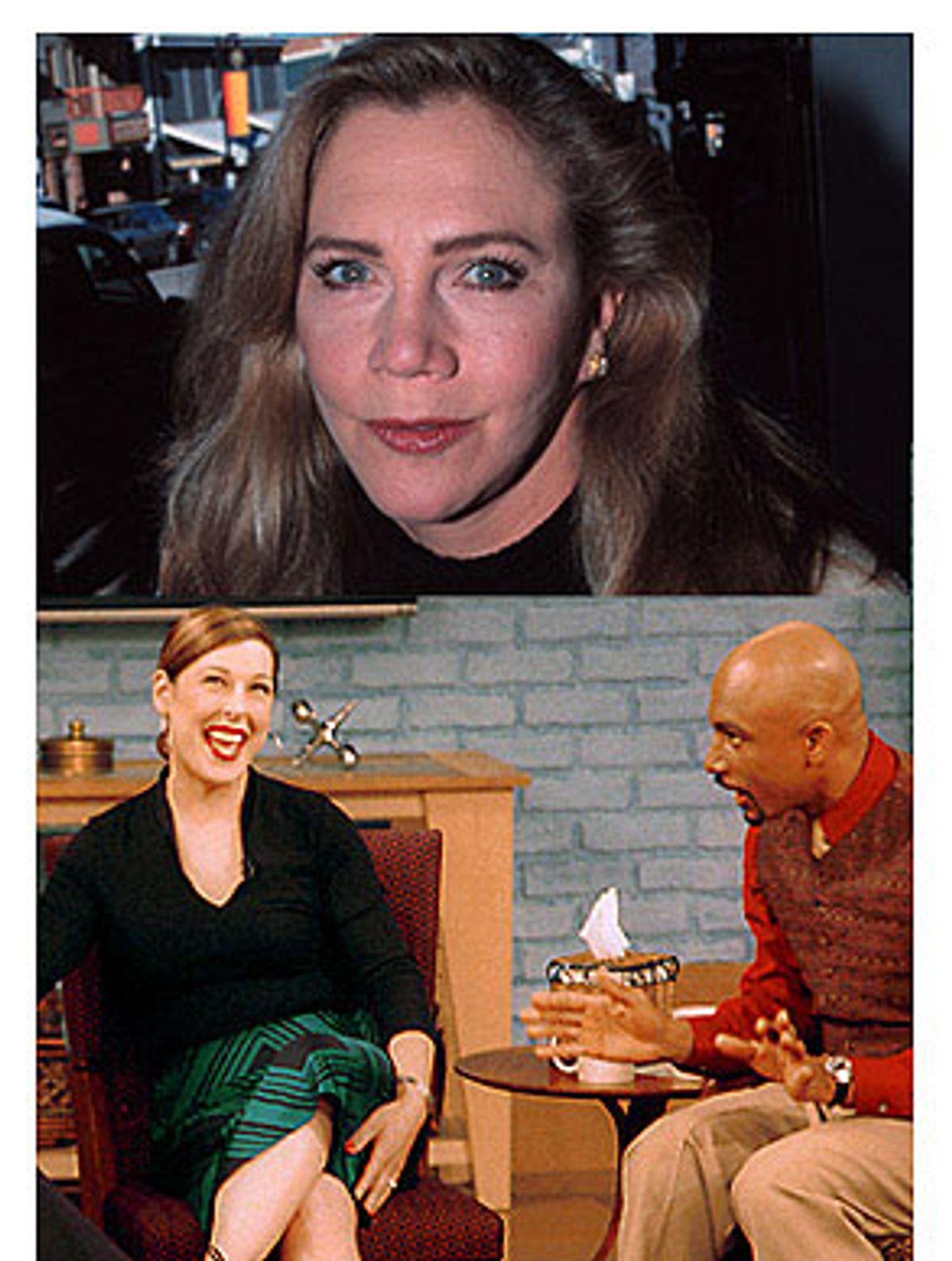

Kathleen Turner was on television recently talking about her pain and suffering. "The damage that I have, the damage I'll always have could have been prevented," the actress told "Good Morning, America" host Diane Sawyer on Feb. 19. Sawyer was sympathetic. Turner, she knew from a previous interview, had been battling rheumatoid arthritis for over a year now.

"You're still in pain?" Sawyer asked.

"Well," Turner responded, "as they say: only when you walk."

Turner then went on to mention a Web site, www.ra-access.com, where fellow sufferers could get help. Sawyer eagerly repeated the site's address in case viewers missed it.

All of this would have been your standard bit of early-morning show chitchat if Turner had not been paid by two drug companies to speak out about her illness. "She gets a fee," confirms Robin Shapiro, a spokeswoman for Immunex, a bio-pharmaceutical company, which along with Wyeth, funded a media campaign for which Turner was hired to do a number of TV and print interviews.

The two companies jointly manufacture an arthritis drug called Enbrel. They also happen to operate the Web site that Turner and Sawyer plugged as so helpful to arthritis sufferers. The site is a marketing tool for Immunex and Wyeth. Visitors are asked to supply personal information, which, according to Shapiro, is used to send them promotional materials on Enbrel, a drug competing with several others in a multibillion-dollar market for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

These sorts of below-the-radar media campaigns, which blur the line between drug advertising and public service efforts, are now rampant. And increasingly crucial to the success of these carefully orchestrated blitzes are celebrities willing to pour out their hearts about how they or a close relative have struggled with a particular illness -- for a price. In the last few years gymnast Bart Connor, Olympic figure skater Dorothy Hamill, jockey Julie Krone, former NFL coach Bill Parcells, San Francisco 49er legend Joe Montana, actors Rita Moreno, Bob Uecker and Debbie Reynolds have participated in this drill for various drug companies. "West Wing" star Rob Lowe recently embarked on a drug-company sponsored awareness campaign for a cancer-related illness called febrile neutropenia that will reportedly net him $1 million.

"It's become a hugely gray area as to where the stars' charitableness begins and where their financial interests begin," says Barry Greenberg, a Hollywood talent agent whose firm, Celebrity Connection, specializes in recruiting stars for the drug companies. "Maybe Katie Couric wasn't being paid to have a hose shoved up her ass, but the rest of the stars, they're getting something."

In 1997, under growing pressure from pharmaceutical companies, the Food and Drug Administration relaxed its regulations on television advertising for prescription drugs. The industry promptly went on a multibillion-dollar spending spree, bombarding the airwaves with commercials for their products. Having seen the fundraising successes of nonprofit organizations and foundations linked to specific illnesses that used celebrities to raise awareness about health issues, pharmaceutical flacks made immediate efforts to tap into this star power. Joan Lunden was hired to hawk the asthma drug Claritin in 1998. Bob Dole flacked for Viagra in 1999.

These first ads were like most others that featured celebrity endorsements: The star's connection to the company was obvious; the pitch was straightforward promotion. But, as one marketer for the drug industry puts it, "There was a backlash." It occurred to consumers and advocacy groups that it could be dangerous for well-trusted public figures to be recommending drugs with serious side effects. In some cases, the celebrities with transparent links to drug companies saw their reputations tarnished or skewered. Suddenly they were irresponsible -- or a joke.

So the drug companies tried a different tack -- celebrity-driven public awareness campaigns that completely obscure the financial relationship between the star and the drug company, while allowing both parties to avoid any talk of side effects or potential problems with the drug. With all hints of drugs and money hidden from view, celebrities were again willing to sign up, taking fees as high as $1 million to do a raft of television and newspaper interviews in which they speak about a particular illness and urge sufferers to seek treatment.

For the most part, the celebrities don't mention their sponsor or its product by name, but instead urge people to go and see their doctors about the latest treatments, or, in the case of Turner, suggest that viewers or readers visit a specific Web site that offers information about a condition.

This approach allows the drug companies and their celebrity hires to insist that they're doing a public service, not to mention providing the public with compelling human-interest stories and sneak peeks inside the private lives of movie and television stars. But some will acknowledge an ulterior motive. "Well, sure," says Immunex's Shapiro about the Kathleen Turner campaign, "the more people who know about rheumatoid arthritis, the more people who go to the doctor's office and find out about our breakthrough treatment."

These awareness campaigns also happen to be a way for the drug companies to avoid the remaining FDA regulations on TV advertising of prescription drugs. In a straightforward television commercial for a drug, viewers must be told about the drug's major side effects or be directed to another source -- a Web site, or 800 number, for example -- where they can get further information. Awareness campaigns are exempt from these restrictions because the FDA doesn't consider them to be advertisements. Thomas Abrams, who monitors marketing by the pharmaceutical industry for the FDA, says the agency would only take action against a drug company if the star employed by the company greatly exaggerated a drug's benefits. Otherwise, Abrams says, celebrities, like any other citizen energized by a cause, are free to say whatever they please.

On May 23, 2000, actress Olympia Dukakis appeared on the Fox News channel to talk about her mother's battle with post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN), a debilitating condition brought on by shingles. Her mother "would sit muted in pain," Dukakis told viewers. "She couldn't even touch her hair. That's how painful it can get." Dukakis then went on to say that others need not suffer like her mother did, that there are new, better treatments out there. "In fact, there is one solution," she said. "It's called lidocaine or lidopatch."

PHN sufferers who went to their doctors and asked about lidocaine or lidopatch would have found out that there is only one drug Dukakis could have been speaking about, Lidoderm. Lidoderm is a patch that right now is the only formulation of lidocaine approved by the FDA to treat PHN. It also happens to be manufactured by Endo Pharmaceuticals, which was paying Dukakis to do the Fox interview. "Yes, she was compensated," says Sherri Michelstein, who was hired by Endo to organize the media campaign. (Endo and Dukakis' representative both declined comment).

Of course, the television audience never learned about Dukakis' ties to Endo. "The tireless actress is constantly on the move," Fox anchor Paula Zahn said in introducing Dukakis. "But now, she's set her sights on helping to ease the pain of more than a million Americans."

By mid-1999, pop singer Carnie Wilson weighed close to 300 pounds and was, as she later told an interviewer, "desperate." She felt depressed, suffered from diabetes and a sleep disorder, and was barely able to get her 5-foot-3 frame in and out of her car. Her career had largely been on a downward spiral ever since the breakup of her rock group Wilson Phillips.

It happened that her former manager, Mickey Shapiro, had started a health-related Internet company whose board of directors included surgeon Jonathan Sackier. Sackier suggested to Wilson that she undergo gastric bypass surgery, which meant having her stomach stapled down to the size of a fist so she couldn't eat as much. (Wilson also has said that Roseanne Barr urged her to consider the option.) Wilson not only agreed -- she volunteered to let Shapiro's Internet site broadcast the procedure live.

Over the next three years, Wilson became the nation's poster child for the benefits of gastric bypass. "Since the surgery, I feel lighter, I feel sexier -- inspired," a 150-pound Wilson told People magazine (and many other media outlets) in April of 2000. People did a total of three stories on Wilson, two of them front covers. She was also interviewed on ABC's "Good Morning, America" six times and on the news magazine "20/20" five times. Asked once why she chose to go public about her obesity, she said, "It's just -- if it can help people, then I'm happy to do it."

But it wasn't just about helping people, unless you count Wilson as one of those people, and throw in some cash. Wilson gets paid to do appearances where she talks about her surgery. Her corporate sponsors are Tenet Healthcare, a for-profit hospital chain that does gastric bypass operations at its facilities; and Vista Medical Technologies, which makes the medical equipment needed to perform the procedure.

The fourth business partner in Wilson's extraordinarily successful media campaign is her former manager's Internet company, which has since morphed into an L.A.-based public relations and marketing firm called Spotlight Health. Spotlight now focuses almost entirely on celebrity-driven health awareness campaigns.

Wilson doesn't see anything wrong with taking money from Tenet and Vista. "I don't need the money. That's not why I do it," she said. "Every day of my life I am committed to people and helping them get healthy." Wilson says she doesn't believe her corporate connections need to be revealed to the public. "That's all bullshit," she says. "We're talking about health issues and being able to help somebody by making them more informed."

There is no doubt that Wilson's outspokenness has played a huge role in popularizing a risky, complicated and expensive procedure. The American Society for Bariatric Surgery credits her with having a major role in publicizing the benefits of gastric bypass, which has seen a huge surge in popularity since 1999. Vista Medical Technologies, which also makes postoperative vitamins for gastric bypass surgery and runs training courses on the procedure for doctors, has had its revenues double since Wilson began her campaign. According to the Vista's CEO John Lyon, it makes little difference that Wilson doesn't mention Vista by name in any of her media interviews. "The rising tide lifts all boats," he says.

As for Spotlight Health, its efforts with Wilson prompted a shift to a lucrative new business. The company recently launched a campaign that features the unlikely combination of Olympic skater Tara Lipinski, former FBI profiler John Douglas, former Vice President Dan Quayle and former Jethro Tull flutist Ian Anderson all speaking out about deep vein thrombosis. Its sponsor is Aventis, which makes Lovenox, a blood thinner used to treat the condition. Spotlight Health's president Richard Hull says celebrities in the company's employ are not required or encouraged to mention a drug company by name, but then again, "If it's appropriate, there's no reason why the sponsor's name can't be mentioned."

Even though the FDA has no legal responsibility to regulate these public awareness campaigns, there are widely accepted ethical guideliness in the media that would seem to demand that the public be told when a celebrity on a show is shilling for a drug company. In fact, this almost never happens. According to ABC spokeswoman Lisa Finkel, deadline pressure makes it hard to investigate a celebrity guest's hidden agenda. The result, she says, is that ABC never knew that both Turner and Wilson had corporate backers. "It's troubling that certain of our guests have not disclosed their paid relationships with these companies," she says.

But it's not that hard to find out who's really behind a health awareness campaign. A quick search of Nexis will turn up press releases put out by public relations firms or the drug companies' themselves announcing their affiliation with a particular celebrity. Spotlight Health lists all of its corporate sponsors on its Web site, www.spotlighthealth.com. "Our policy is full disclosure," says Spotlight CEO Richard Hull.

Assuming that individuals in the media have the skills to obtain this information, it seems less a matter of the media being fooled than of the media not really wanting to know. Celebrities like Christopher Reeve, who doesn't have any affiliation with a drug company, have left the public ever more hungry to hear stars describe their battles with illness. Drug companies are now exploiting that hunger; the news media is more that willing to let them do that if it means access to celebrities. As one ABC News executive said, "The bottom line? If a celebrity has a compelling story to tell, we want to tell it."

Shares