My daughter, these days, is in pictures. Not as in Hollywood, but as in photographs taped to the walls of my prison cell. The cluster of photos tells a story that, in the words of Sophie, begins with, "Remember, Dad, I've had a happy childhood ... so far."

There we are in the maternity ward, proud dad holding a newborn up to the camera. Weeks later at home, me exhausted on the couch, her clinging to my chest like a little tree frog. The two of us on the hardwood floor of the kitchen, me coaxing a spiky-headed baby into crawling. There's a toddler in a Jolly Jumper wearing a striped stocking hat, eyes lit with the glee of a bouncing new life. Then come the early Christmases -- each wearing a new bathrobe, Sophie on her feet by now, buried to the ankles in Barbie accessories and piles of torn gift-wrap.

As she grows foot by foot, we stand father to daughter in our snorkeling gear on a beach in Cuba, or sit splay-legged in the sand, both wearing lopsided Panama hats in Mexico. In another photo I'm piggybacking a tuckered-out first grader, both of us in matching Helly Hansen rain gear, making our way home from a West Coast hike.

Interspersed are the earnest studio poses from each of her school years -- from kindergarten through early grades -- all hair ribbons and missing front teeth. As she turns into a poised young girl leaving grade five for middle school, I begin to disappear from the collage. Now the pictures are of her alone, sitting on our favorite beach pointing to the rock we used to sit upon, or of her each year holding up a Christmas gift toward the lens.

There is a thinness to her smile in these pictures, carefully held, as if that smile might break into something else the moment the shutter clicks. Her attempts to bridge the distance, to include me in the moment, are the hard evidence of my absence. When a parent breaks the law, the fractures run straight through the child.

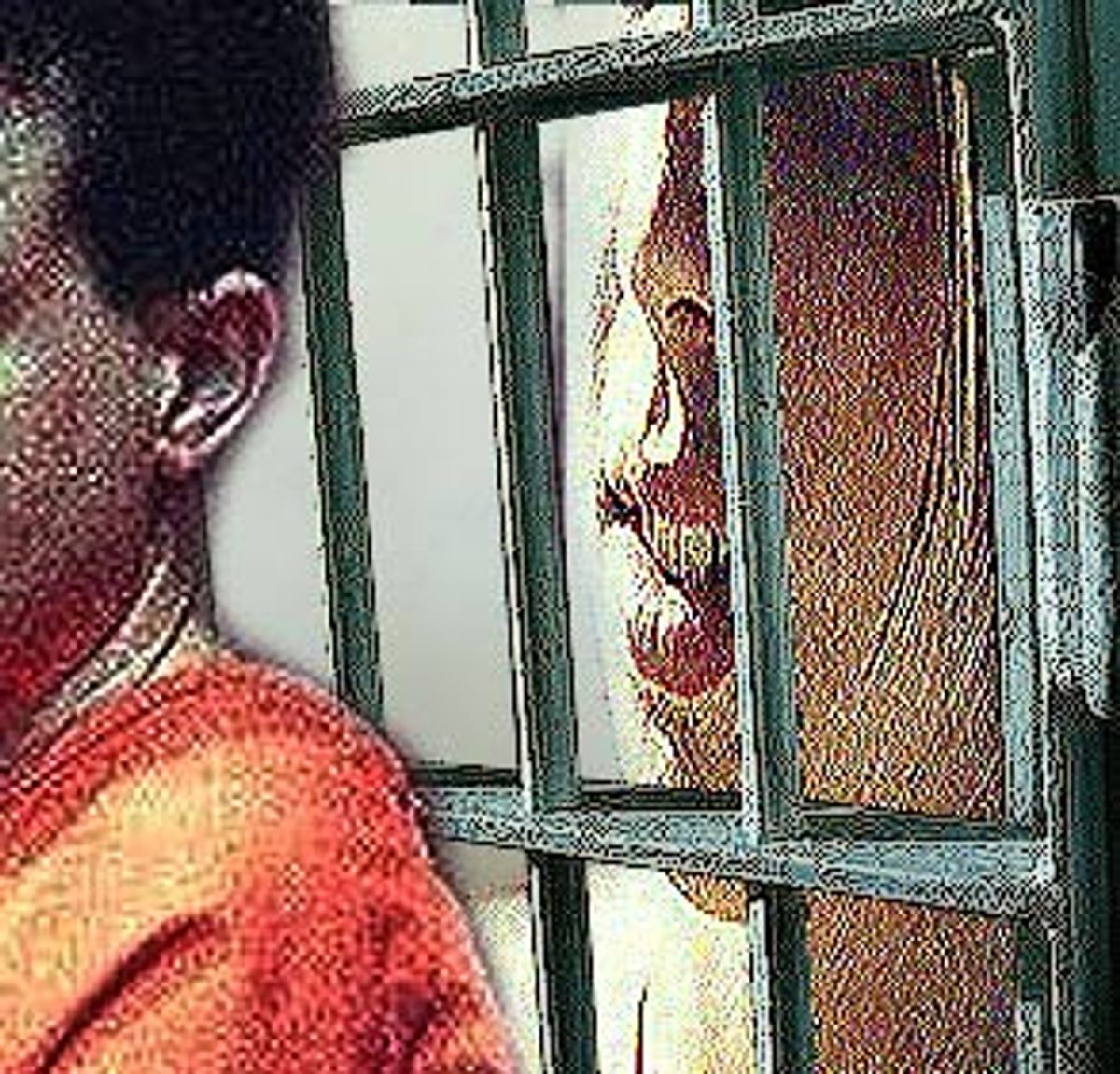

It has been three years since Sophie first put her fingertips up to the glass that separated us in the visiting booth of the remand center where she visited me twice a week. She knows more about prison than any young girl should have to know, and she carries her freight of grief the way other kids her age carry their backpacks to school every day. When I was first arrested she was broken with grief, sobbing "Dad's never coming home, is he, Mumma?" to my wife through sleepless nights. Grief turned to anger -- she cut my face from the photos in her album; anger turned to resignation -- she glued them back in again. Acceptance came too, like the day she said the Department of Corrections should actually be the Department of Mistakes.

Since the day before Christmas, in 1999, when I was sentenced to 18 years for armed robbery, I have been transferred through four different penitentiaries, ultimately landing in a medium security facility an hour's drive from our home. Sophie has grown more than a foot, stapled some jewelry on her face, and entered into her teens. To paraphrase Dickens, "For teenagers, it is the best of times, for parents it is the worst."

How does one remain a parent from prison? You can't say to a child, "Hang in there, sweetie, I'll be home in 18 years." It is unimaginable to them. Yet we remain bound to our children, and they to us, in as primal a way as any parent, by our DNA and our love. A wise psychiatrist, who did a pretrial assessment of me, set down his pen afterwards and said, "This isn't about you anymore -- you are going to prison for a long time. It is now about a little 10-year-old girl, about showing her that no matter how badly we screw up our lives, no matter how terrible the mistakes we make, it can be survived. There can be redemption."

So we survive. We cope. We carry on. We are allowed private family visits every two months -- 72 hours to ourselves in a cottage near the prison's front gate. We watch her favorite television shows together, read, kick a soccer ball around the yard, and fight over who gets to lick the cake batter from the mixer blades. We don't try to pretend -- we live in the knowledge that our lives have been made different -- but during those 72 hours there always comes a few seconds where it all feels real again.

As we travel these years, separate yet bound, I have learned my role is to listen to her life. Sophie writes me letters, and, occasionally, stories. It is to these stories that I pay particular attention. Although the narrative itself is a gateway to her world, I have to listen carefully at the level of the word because these stories are more prism than magnifying glass.

I enter the "fiction," sometimes witnessing behavior I would rather know nothing about. It can be hard to learn she got drunk on the beach, but as a parent who is not present in her day-to-day life, my response must be different. I have to know that experience will shift, the present version will change.

The other week I received a heads-up from my wife that a letter of great unburdening from Sophie was in the mail; she followed this announcement with the assurance that Sophie had already moved on. When my daughter's letter arrived -- she wrote that she'd wanted to die ever since I'd been gone, but she wouldn't "do anything" because she knows it would hurt me too much -- and I finished reading it, I walked out to the point and stared down across the waters to the city on the faraway shore. I swelled with a great longing to be there because I knew, somewhere in the downtown core, there was a young girl dragging her mother by the elbow, trying to draw her into a tattoo shop.

Grief on Monday, tattoos on Wednesday. I already knew my daughter wouldn't get her tattoo that day, but I also knew that the same determined heart that allowed her to have, and move through, grief, would one day win her what she desired. To know with certainty that everything she needed was already inside her allowed me to lift my head.

She's written once again since then -- says she's sealed all her hurt in a time capsule and buried it in the garden where the love-in-a-mist and forget-me-nots grow. We'll open it together, she says, when I get home.

Shares