Patty Estrella drives her Chrysler Sebring convertible down a dirt road, pulls onto a small hill, turns the car around and throws it into park. On the right, small suburban houses litter the landscape; to the left lies the blue expanse of Buzzards Bay. And straight ahead sprawls the subject of our tour: the abandondoned Atlas Tack factory, a 24-acre, arsenic-laden site that's dominated by empty brick buildings with broken windows, a smokestack and -- lying a few yards from where Estrella and I sit -- reed-filled marshland that leaches poison into the bay, its mud and its clams.

"You can't see pollution," Estrella says, running a hand through her frosted blond hair. "But you can see the beauty of the ocean and the tragedy of it being ruined."

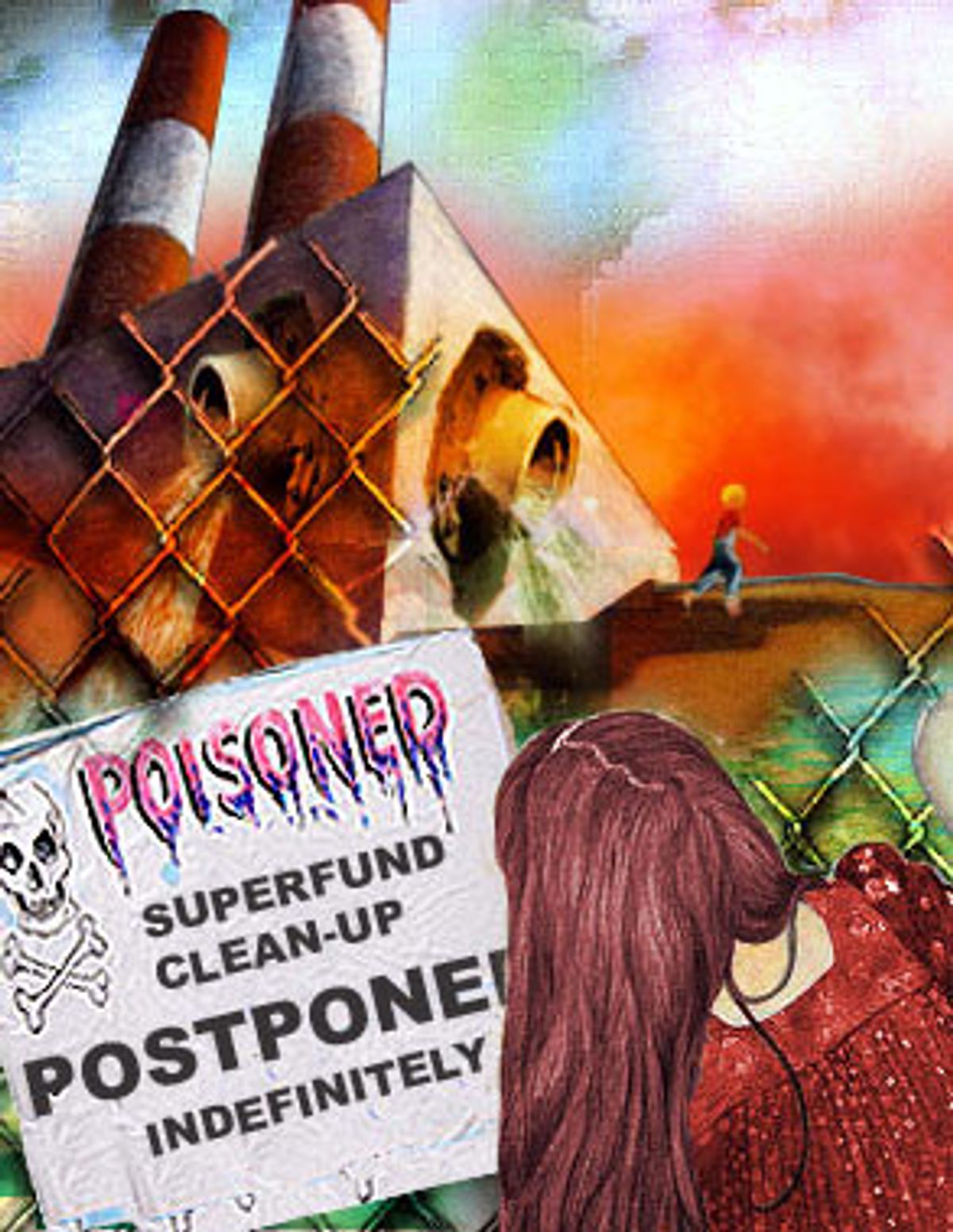

She points to a downed strip of fence that lies in the marsh, glistening like a silver bridge. "The fence has been down for a while," she says. Later in the day, I see a group of kids playing nearby; Estrella's teenage son tells me that sneaking into the site has become a Fairhaven rite of passage.

It doesn't look as though it would take much to get in. Getting the factories and poisons out, however, is another story -- as Estrella knows. She has been fighting for an immediate cleanup of the area ever since the mid-'80s, when Atlas Tack abandoned the site, and when she and her husband bought the tiny ranch house that abuts what state, federal and independent studies have found to be contaminated property. She's complained at community meetings, formed neighborhood watchdog groups, spied on the company from her attic window. Her closets overflow with Atlas Tack-related documents.

For a while, particularly during the late '90s, it looked as though Estrella's efforts were not in vain. State officials had already cleaned up a contaminated lagoon in the late '80s and in 1999, after the city sued, Atlas Tack demolished one of the site's more dangerous buildings. One year later, the EPA offered an $18 million cleanup plan.

"I thought then that it might actually happen," Estrella says.

But two years after the plan was approved by town and state officials, the site remains nearly as dangerous as it was a decade ago. With its condemned buildings and contaminated ground -- more than 54,000 cubic yards of soil, debris and sediment contain "heavy metals, cyanide, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and pesticides," according to the EPA's most recent report -- the site is a health risk to any human or animal who visits the area or ingests shellfish harvested nearby. But even though the site is tainted enough to find a place on the Superfund list -- a running tally of the nation's most polluted areas, each of them eligible for federal Superfund money for cleanup -- Atlas Tack's poisons won't be removed anytime soon. On June 24, the EPA told Congress that it planned to cut funding for 33 Superfund sites. A handful of those properties received last-minute funding July 22, but Atlas Tack, its cleanup once scheduled to start in April, is currently destined to remain unfunded and untouched.

Estrella and the other 7,200 residents who live within a mile of the site are the most obvious victims of the decision. Unless more money becomes available, their only recourse to living in the toxic shadow of Atlas Tack is to move. Barring that, they have to derive what little comfort they can from EPA studies showing that the site's poisons are leaking into the ocean, not into local neighborhoods, perhaps delaying the seemingly inevitable impact on their health.

But it isn't just the prospect of a future living next to contaminated land that residents of Fairhaven, and other Americans affected by the Superfund cuts, find devastating. It is the fact that the decision to leave them mired in contaminants has huge benefits for the companies that dumped them. Companies like Atlas Tack, and its parent company, Great Northern Industries, are the happy beneficiaries of the Bush administration's new Superfund policy. By refusing to clean up the sites and then collect costs from the responsible parties, Bush and the EPA have essentially given the nation's biggest corporate polluters a multimillion-dollar reprieve -- at a huge personal cost to less influential citizens.

Environmental activists, local residents and politicians who have fought for Superfund cleanup say they are not surprised by the move, crushing as it is to all of them. The Bush administration never liked the Superfund program, says Scott Stoermer, spokesman for the League of Conservation Voters. "They see it as an inefficient government program that puts too much of a burden on corporations."

But EPA officials dispute this conclusion. In a July 18 editorial in the New York Times, EPA administrator Christine Todd Whitman stressed that the agency remains dedicated to the Superfund cause. Designates like Atlas Tack, Whitman argued, could get cleanup funding as early as the end of the year. But the Bush administration has never suggested it would reinstate the corporate taxes that fed the Superfund until 1995, and with the cleanups at Atlas Tack and more than a dozen other sites delayed indefinitely, critics are struggling to take the EPA at its word.

Fairhaven's residents in particular see the cuts as one more punishing corporate perk, an extravagant handout from the nation's CEO in chief. And in the case of Atlas Tack, they say, it is nearly impossible to rationalize a regulatory break that so clearly endangers the well-being -- perhaps the lives -- of an entire community.

Fairhaven's history has been intimately tied to Atlas Tack for more than a century. Henry Huttleston Rogers, a well-known robber baron who made millions as a vice president of Standard Oil, bought Atlas Tack and brought it to Fairhaven in 1901. Town history celebrates the factory as a gift. Rogers grew up in Fairhaven; he paved Fairhaven's roads and built its schools, the library and the impressive Unitarian church, a Gothic landmark. Atlas Tack, the theory goes, was built to ensure that the members of Rogers' beloved community would always have a place to work.

The owners who took over Atlas Tack after Rogers died in 1909 stayed true to his intentions. Even after Great Northern Industries bought Atlas Tack in the mid-'60s, local residents could usually find work producing shoe eyelets and other metal at the factory. Sometime in the '40s, wastewater laced with chemicals from electroplating, acid-washing, painting and other activities began to be discharged into a lagoon down by the marsh. There was occasional chatter about the greenish-yellow liquid; but throughout the '60s and early '70s, even as public knowledge of toxins began to rise, no one found the courage to ask questions about the sludge.

"The town used to accept it because a lot of people worked there," says Irving Macomber, 74, a Fairhaven resident since birth who remembers playing near the lagoon in the '50s. "They didn't want to say anything because they didn't want to lose their jobs."

State officials, however, had a hard time staying silent. In the '70s, for example, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Quality Engineering (DEQE) tried to enforce a law mandating that polluted water be treated before being dumped. Great Northern Industries, responsible for the routine discharge at Atlas Tack of wastewater containing cyanide, arsenic, cadmium and other poisonous heavy metals, simply stonewalled the effort.

"They've been very difficult from day one," says Paul Craffey, the agency's (now called the Department of Environmental Protection) chief project manager for Superfund sites in southern Massachusetts. "The national pollution elimination system requires pre-treatment of wastewater before putting it into the town sewer, but they fought that for years. They had been putting untreated water -- throughout the '60s and '70s -- into the lagoon and it took them a long time to comply."

Four calls to Great Northern Industries seeking comment on the company's business practices were not returned. The company's former lawyer, Kevin O'Connor, also refused to comment and two of the company's environmental consultants failed to respond as well.

Craffey, in his roles as a state and EPA official, has been working with and studying Atlas Tack for more than a decade. He says that Great Northern finally started following the pre-treatment rules in the late '70s. But by this time, most of the serious damage had been done. The untreated wastewater had already been discharged from troughs in the buildings, through leaky pipes, out into the unlined lagoon. And according to an Oct. 19, 1982, state report that was sent to Atlas Tack, laboratory analysis of sludge samples in the area "indicate that the contents of the Atlas Tack lagoon ... exhibit a potential harm to the environment resulting from improper storage and disposal." Animals and people -- anyone and anything that comes into contact with the area, state officials argued -- would run an increased risk of health problems, cancer included.

Other documents from the early '80s -- made public through court records -- show that state officials didn't just warn Atlas Tack of the site's dangers; they also demanded that the company clean up the mess. The company, however, did nothing. Atlas Tack failed to respond to a series of notices in 1982 and 1983, including one showing that groundwater was potentially being poisoned by the lagoon.

In 1984, the state decided to sue Atlas Tack for violations of Massachusetts' pollution laws. R.L. Lewis, president of Atlas Tack at the time, initially agreed to clean up the area. But after signing a consent decree, the company quickly "fell behind in its compliance" according to a story in the March 2000 edition of White Collar Crime Reporter. So the state moved in, assuming control of the area in 1985, and selecting a contractor who finished cleaning up the lagoon.

The state billed Atlas Tack for the work, but the company refused to pay. Claiming that the cleanup costs were too high, Atlas Tack instead sued the state, the contractor and even its own insurer, who refused to pay for the cleanup because it had never been notified of the initial settlement. Atlas lost every case; Craffey says the lagoon cleanup cost the state between $500,000 and $1 million. Atlas Tack, at the behest of court officials, eventually paid most of the bill.

But the state's legal costs were never recouped and Atlas Tack has paid far less than it owes. There's still a lot of work that needs to be done. The dilapidated buildings, an identified fire hazard, need to be demolished; the land below and around them remains dangerously poisoned to this day. More than 200 EPA soil samples taken over the past decade show that about half of the marsh area is contaminated with dangerous levels of metals and cyanide, "causing an ecologic risk to the wildlife," according to EPA reports. Everyone who comes into contact with the area -- the kids who visit the site for kicks, scavengers Estrella has seen stealing bricks, visitors who eat shellfish pulled from the area -- is being exposed to toxic chemicals. Atlas Tack, though made aware of these dangers, refuses to offer assistance.

On the rare occasions that the company did what it was told -- for instance, when Atlas Tack put up the fence that's now fallen down -- the solutions rarely lasted. Calls to the company's Boston office are greeted with a mysterious "hello" rather than identification of the company, and messages are rarely, if ever, returned. "They want to be as inconspicuous and unknown as possible," says Jeffrey Osuch, executive secretary for the town of Fairhaven, a city employee since 1988. "They want to avoid being held responsible for the site."

Atlas Tack may also want to avoid the possibility of a massive tax bill. Fairhaven records show that the company hasn't paid taxes since 1990. The town is now owed more than $180,000 in back taxes and interest, according to Osuch. (Atlas Tack failed to return calls on this matter as well.)

Atlas Tack gained a new enemy in 1988, when the EPA nominated the company for Superfund status, a designation that meant its factory site was one of the country's most polluted areas. When the nomination was approved two years later, the site was given priority, with 1,200 others, for immediate cleanup, with federal funds available to the polluters to expedite the process.

Estrella's first reaction to the Superfund listing was shock. "I didn't know it was bad enough to be put on the Superfund list," she says. But then she remembered what it was like to live on the street a decade earlier, when she and her parents lived a few doors down the street from where she now lives, which runs parallel to Atlas Tack's property line. There were signs then that pointed to environmental dangers.

"Pets used to go into the site and come back blue from the chemicals," Estrella recalled. "We had one cat down the street that would regularly come back with blue paws. It looked like it was a punk rocker."

Estrella visited the site with a Great Northern representative, Osuch, and a few other town officials in the early '90s. The tour was organized by Great Northern "so we'd see that it wasn't as bad as the EPA claimed," Estrella says. But after touring the main building's plating room, the source of much of the area's waste, Estrella began to feel sick. "I came away with an upset stomach and I had a headache for 3 days," she says. "I thought it was obviously a biohazard."

State and federal officials agreed. After completing initial assessments, they pressured Atlas Tack to remove asbestos from all the buildings and to demolish the main building, which was structurally unsound. Years later, in 1998 and 1999, the company did the work -- sort of. Atlas Tack removed the asbestos in the main building and demolished it, but never hauled off all the debris. Asbestos in the other buildings was left in place, even though pipes with the carcinogenic material could easily be seen through the buildings' windows, Craffey says. The EPA had to step in again.

Even after the building was torn down, the area remained contaminated. According to the EPA Web site description, which summarizes a series of studies on the area, the on-site soil is contaminated with volatile organic compounds (VOCs), heavy metals, including lead, pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) -- poisonous materials known to cause cancer and other illnesses. Anyone or anything that comes into contact with the area could be in danger.

Atlas Tack has consistently argued that the EPA studies are flawed, that the property never should have been listed as a Superfund site in the first place. In a Feb. 19, 1999, response to the EPA's proposed remedy, the company claimed that tests used to determine that the site was contaminated only focused on the most polluted areas, and never proved that the chemicals had been flowing into the groundwater or the ocean. The proposed remedy -- demolition of the buildings, removal of polluted soil -- is nothing more than, in the words of Atlas Tack's lawyer, "a pointless attempt to stop a contaminant migration process that is not occurring at levels above EPA's cleanup goals." Citing its own experts, Atlas Tack went on to argue that "The EPA cannot proceed to implement such a plan. Doing so would be a waste of time and taxpayers' money."

Craffey disagrees. Studies conducted at the site after Atlas Tack joined the Superfund list confirmed that migration levels posed a threat to the community. Atlas Tack, he argues, is just plain wrong.

"[Atlas Tack and its consultants] did a quick sampling of the plants that found the grasses had no contamination, but look at the dirt," Craffey says. "It's contaminated. The plant is irrelevant because the animals who eat it don't wash it off. Ducks don't have teeth so they put gravel in their mouths to break up their food. They're being affected."

But if people like Estrella and Long, who both live only steps from the site, are healthy, isn't the community safe? Isn't the EPA justified, as it claims, in directing funds to more dangerous areas?

Not necessarily. Craffey argues that Atlas Tack shouldn't fall through the cracks simply because other sites might be more contaminated. The site, he argues, poses a present and future danger. The fact that nothing has been done for so long only increases the possibility of harm: Buildings are closer to falling down, and the public is not as cautious as it should be. Some people don't even seem to notice that the area is poisoned. "We saw evidence of people with plates and forks over there by the water [within a hundred yards of the poisoned area]," Craffey says.

Fairhaven kids may be the ones most at risk. They are fascinated by the site -- many go there as a matter of local tradition. Even Brandon Estrella, who had been warned repeatedly by his mother about the site's dangers, felt the need to sneak in. He was 12 or 13 at the time, which is when most kids have the urge, he says. "It's a Tom Sawyer, Huck Finn sort of thing," he says. "Something you look back on and say, 'Wow, that was kind of stupid.'" Stupid, but incredibly easy to accomplish.

Some residents now believe, perhaps justifiably, that the site will only be reconsidered for cleanup if someone dies. The smokestack will eventually come down through the powers of decay, so will the buildings. Macomber, whose 16-year-old granddaughter lives within a few hundred yards of the site, hopes that no one will be trespassing when they do. "It's a real danger for the kids," he says.

And then there are the potential health risks, which might only begin to show after years of exposure to the toxic chemicals. Once people begin to die or become ill or detect birth defects, cleanup might come, but obviously too late -- at least for Fairhaven residents. When one begins to consider future harms, Craffey says, the site begins to look like an onion -- "There are several layers and the more you pull, the more it makes you cry."

The suffering now is mostly related to fear and frustration -- and a sense of betrayal from a company that locals served well for decades. "It makes me mad because the government said they were going to clean it up," Macomber says. "We" -- the nation, government and especially big businesses like Atlas Tack -- "lived high off the hog for years; it should have been cleaned up by now."

Now that the EPA pressure is off, however, it is unlikely that the company will foot the bill for cleanup simply because it is the right thing to do. Great Northern and Atlas Tack have rarely paid for the cleanup or safety measures that weren't court-ordered and first covered by Superfund or state funding. In fact, the company already has a large bill outstanding. Along with the tax bill, there's the costs of cleanup activities already completed that haven't been paid. According to Craffey's estimates, the EPA has spent more than $4 million assessing the site and doing initial cleanup -- not a dime of it has been paid for by Lewis, Atlas Tack or Great Northern.

Some companies take responsibility for their property: AVX, Aerovox, Belleville Industries are just a few of the companies that have agreed, with little argument, says Craffey, to help clean up their polluted Superfund sites. The area that these particular companies are responsible for -- in New Bedford, only a few miles away from Fairhaven -- is still on the Superfund list and may never leave but the companies continue to contribute funding.

Whitman emphasized this point in her New York Times editorial, noting that 70 percent of Superfund cleanup costs are paid for by polluters. But what she failed to mention is that many of these polluters only paid because they had no choice. The Superfund -- as a pool of money that allows the government to complete massive cleanups, regardless of corporate stonewalling -- was the EPA's greatest weapon. It was the proverbial big stick used to beat the worst corporate polluters into submission. Without the guarantee of funding from corporate taxes -- which expired in 1995 -- and without a steady commitment from Congress and the White House, the cuts to Superfund create a vacuum of authority. Not only is there no real penalty for contaminating the environment, there is also an incentive to fight any demands to be clean.

The lesson here is that if a company delays long enough, it will get a break from the government. There is also an implied promise of laxity for future polluters. Why should a company spend money on clean and sustainable production if it is cheap to pollute for a profit?

The message in the Superfund cuts frightens and depresses people like Estrella. She's appalled by the prospect of inaction, the possibility of more families being poisoned and the inability -- now enforced by the government -- of communities to hold a local company responsible. But ultimately, it comes down to what she sees every day. Back in her car, under a summer New England sun, she still thinks about what the site might have looked like if it were already cleaned up.

"It shouldn't be left with all these shitty fences," she says. "This could be bird sanctuary."

Shares