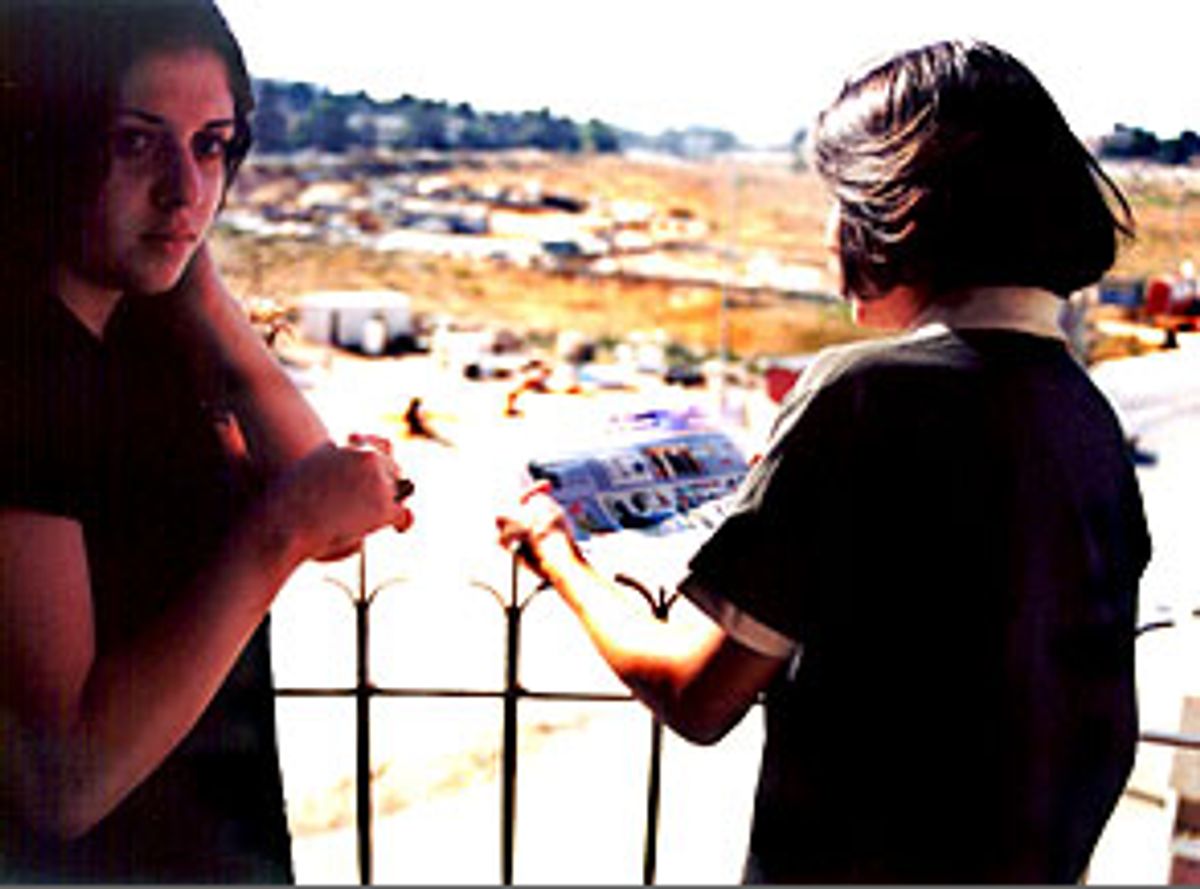

Ahmed Ayysh points to the horizon and smiles broadly for the first time all day. "There's my home," says the 23-year-old Palestinian. "You see that mountain there? That's where I live."

We are standing in the town of Ar-Ram, part of Jerusalem's northern sprawl, a strip of crumbling buildings and dust between two checkpoints that divide Israel from the occupied West Bank. A trash fire next to the road has been burning for five days. From here, the road goes through at least one more checkpoint on the way to Ayysh's house in the West Bank town of Biedo.

With a well-paved road and no roadblocks it would be a 10-minute drive, but for Ayysh the journey has taken much longer. Biedo, like most of the West Bank, is under curfew and Ayysh's orange West Bank identity card prevents him from entering Israel. But Ayysh has taken four taxis through back roads and walked three miles -- and, he says, been shot at by Israeli soldiers -- just to attend a meeting.

The meeting that has drawn Ayysh and other young Palestinians to Ar-Ram is being held by a group called PYALARA, which stands for the rather cumbersome title "Palestinian Youth Association for Leadership and Rights Activation." The group was founded three years ago to give Palestinian young people something in desperately short supply here: constructive work, a vision of the future, hope. With a budget of just $144,000, most of it from UNICEF, the International Red Cross and various European Union groups, its tools appear modest -- a youth newspaper with a circulation of 10,000, counseling for Palestinian youth by their peers, various seminars and training sessions. But judging by the young Palestinians who say the group has saved them from despair -- even from becoming suicide bombers -- and given them some purpose, they are effective.

The situation in the occupied territories has recently become catastrophic. Massive Israeli military incursions, curfews and economic closures following Palestinian suicide bombings have devastated the feeble Palestinian economy and brought normal life to a standstill. The U.N. estimates that about half the population is now living below the $2-a-day poverty line. There are fears of widespread malnutrition.

At least a third of all adults are jobless -- much higher by some estimates -- and those who have jobs are frequently unable to get to work. Schools are frequently closed, hospitals and medicines often unreachable. Hundreds of thousands of people are confined to their houses around the clock, except for a few hours when Israeli authorities let them out to go shopping, by the curfews which have now been in place for three months in most West Bank cities.

The situation has taken an especially severe toll on Palestinian young people, who make up half of the three million Palestinians living in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Part of that toll is literal: Of the 1,888 Palestinians who have been killed since the start of the Al-Aqsa intifada two years ago, 306 were under the age of 18.

But part is invisible.

In a recent piece in the Israeli newspaper Ha'aretz, the Palestinian writer Sam Bahour wrote, "If my youngest daughter exemplifies the effect of the curfews on Palestinian children, then her first set of words -- dabbabeh (tank), naqelet jonnood (armored personnel carrier) and tayyara (fighter airplane) -- depict the challenge of rehabilitating an entire generation that we now face. A ray of hope may be seen in the fact that she sometimes refers to the Israeli soldiers as ammou (uncle)."

The problem is not unique to Palestinian children: Israeli kids, too, have been scarred by the conflict, but they suffer from a different problem, according to Dr. Asher Ben-Arieh of the Israel National Council for the Child, one of the largest children's aid groups in Israel. "It's not a lack of hope here," says Ben-Arieh. "Here it is a development of hate."

Says Pierre Poupard, UNICEF special representative for Palestine, "Seventy-five percent of Palestinian children are facing psychological problems. We have growing frustration and no hope that is turning into despair." Poupard says UNICEF supports PYALARA because of the worsening crisis and because no other organization in the West Bank offers its programs.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

"We are a lot of unique things," said Hania Bitar, founder and director general of PYALARA. One of the few adults working at the center, Bitar stressed that it is the 300 active members and countless other participants, not she, who make PYALARA what it is. "The organization is truly founded and run by the children," she said.

PYALARA participants range in age from toddlers at summer camps to young people in their mid-20s. The group maintains that it has no political agenda, and as a recipient of UNICEF aid it is forbidden to have one, but the idea that any group in the West Bank could be completely apolitical is nothing more than a fantasy. A picture of Bitar with Palestinian Authority head Yasser Arafat looms over her desk, and the PYALARA Web site is filled not with the innocuous tales of self-discovery or bland feature reporting one might expect to find in a publication by young journalists and writers. Instead there are anguished tales filled with fear, anger and sorrow. The viewpoints expressed are the stuff of bitter argument, but the passion, sincerity and urgency in the essays cannot be mistaken.

In a piece called "So Long Bethlehem ..." Elise Aghazarian of Jerusalem, a graduate of Bethlehem University, writes, "Do the Israelis not realize, I ask myself, that in every stone, plant, and human being, there exists a spirit and story and that were they to consider these stories before causing more pain and damage, then they might see their own role in a different light?

"How afraid I feel as the military horror creeps closer. How sad I feel as I see how indifference is growing amongst the Palestinians whose hearts have been broken especially as I know that indifference is more painful and dangerous than anger and is so much harder to heal."

In a piece called "a target="new" href= "http://www.pyalara.org/youthtimes/journal.html"> "A Sleepless Night," a student at Bir Zeit university named Saleem Habash writes, "A sleepless night. My mother and sister spent the whole night sitting with me in bed listening to the sound of tanks coming from the western side of Ramallah. The fear was so intense; we were almost afraid to breathe, and all I kept thinking was, 'When is this going to end?'

"I decided to start writing as soon as I woke up but it was three in the afternoon before my fingers actually touched the keyboard. We had been eating a nice lunch, trying, to the best of our ability, to escape the ever-worsening news for a few short moments, when all of a sudden my sister yelled that there were Israeli soldiers surrounding an unfinished building just opposite our kitchen and that some of them were aiming the gun of a tank in our direction while others were firing wildly in another direction, possibly at yet another suspected 'terrorist.' Boom ... Boom ... Boom ... We ran for what we considered the most secure room in the house, all of us completely terrified.

"I say to you, Mr. Spokesperson, the following: Israel talks about wanting to build bridges of trust and peace, yet its actions in Ramallah, your 'infrastructure of terrorism,' reek of hatred and resentment. I warn you, however, that try as you might, you will never succeed in breaking the spirit of Ramallah or that of its people; on the contrary, the streets will be repaired, homes will be rebuilt, and Ramallah will rise, majestically, from the ashes.

" As for its people, those same men, women and children now locked in their homes, deprived, in many cases, of their most basic needs, such as food and medicine, they will never forget what you did to them, and in all likelihood, they will never forgive you either."

In a piece called "A Scary Tomorrow," 17-year-old Dalia Nammari of Beit Hanina, Jerusalem, writes, "I was born in 1983, which means that when the Palestinian Intifada erupted in 1987, I was still too young to really understand what was going on. I do remember, however, finding a bullet in our garden and the fear that it instilled in me, especially when I was told that it was only one of the many bullets that were being fired at my people by the Israeli occupiers.

"Like many other young Palestinians trying to come to terms with what has happened to our people, I have spent many hours going through the family albums, looking not only at the faces there, but also at the buildings ... buildings that, in many cases, no longer exist and that were reduced to rubble by Israeli tanks and bulldozers. Today, in their place, there are ugly, characterless buildings, built to accommodate the settlers who came to take the place of my kinfolk. What or who gave them the right to deprive us of our land and disperse our families and friends, and what or who gave them the right to uproot the olive trees that our ancestors planted and tended to with such care?"

- - - - - - - - - - - -

In addition to publishing the work of young writers, PYALARA members started counseling other school children two years ago -- about the same time as the beginning of the current Al-Aqsa intifada, which began in September 2000. When a Palestinian terrorist in Jerusalem killed nine Israelis in March, prompting a massive military invasion of the West Bank by Israeli forces, the teenage members of PYALARA held an emergency meeting and decided the counseling was too sporadic to help children in the territories. "We knew we needed the hot line," Bitar says.

One of the first callers was Fatma Mirab of Har Gilo, in the West Bank. Interviewed at a relative's home in Ramallah, Mirab says that her husband had lost his job, forcing their family to survive on rice, sugar and olive oil provided by aid groups. After the Israeli military campaign in March and April, her son, Hassan, 10, began having nightmares. He spent his days lost in a daze and was failing in school, according to school officials. "I dreamt that I am alone," Hassan says. "I was upset because they are shooting and they killed children in Ramallah."

Mirab called the hot line after the principal told her about it. The PYALARA member who answered the call was Rasha Othman, 21, of Jerusalem. "I told her to let him draw pictures so they could discuss them, since he was having trouble talking," she says. "I also set up a meeting between the mother, the school counselor and Hassan."

Almost three months later, Hassan says he feels like a different person. "I feel relieved because I had someone to talk to me. When she told me how to do this I could only say 'Thank you.' I have the nightmares less now."

Several young PYALARA members actually say the group has helped stop them from becoming suicide bombers. "I want to tell you honestly that I thought about [becoming a suicide bomber]," says Lana Kamleh, 16, of Jerusalem, who has worked for the Youth Times, PYALARA's newspaper that is distributed throughout Gaza and the West Bank, and appeared on Palestine TV on PYALARA news programs.

Kamleh lives in the Arab Shofat neighborhood of occupied East Jerusalem, an enclave that is a far cry from the poverty and desperation that marks much of the West Bank and Gaza. Sitting on one of the family's couches, her father Mohammed shakes his head sadly at her comments. "I hate to hear what she says, but I know this is a difficult life," he says as he glides through prayer beads with one hand and runs his fingers through the hair of his 4-year-old son Khalid with the other. "I am a father with five children. I want a good life for Israelis and Palestinians. We need peace."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

The PYALARA office is abuzz today with several activities, as well as the distracting hum that comes from putting teenagers of both sexes together in a small space. A group of 12 kids is discussing calls to the hot line, while others are at a Red Cross training session for summer programs in refugee camps in the area. Some students are also cooking dinner in the kitchen.

Even though the members created the hot line to deal with problems children were having as a result of the current conflict, they say they get calls on a wide variety of topics, from Palestinians of all ages.

"I remember one girl calling who had fallen in love with her neighbor and said she was having problems knowing that she must marry another man," says Louris Mosell, 22.

"No matter what the problem, the best is when they call back and say 'thank you, thank you, thank you,'" says Hiba Soblabin, 21.

Another problem is more difficult for the group to discuss, and they let Bitar explain.

"Some people thought it was a sex hot line," she says as her eyes focused anywhere in the room but on me. "They apologized."

When his stint at PYALARA is over for the night, Ayysh heads over to a friend's apartment where he has been staying, since the journey home can take three hours if he makes it at all. "I need to wash my pants," he says. He owns only one pair besides the ones he is wearing, so he must wash them every other day because of the heat and dust.

The apartment is a dump -- empty refrigerator, four Che Guevara posters and various people slouching on chairs. It doesn't seem that different from the apartment of a typical American college student, except for the posters of Palestinian "martyrs."

Ayysh, a senior at Birzeit University near Ramallah, says he has found little besides PYALARA to be optimistic about. "We have no meaning to our lives," he says. "And before PYALARA I had trouble speaking about my feelings. Now I speak with thousands at (the university)."

After getting turned away at the checkpoint for three days, Ayysh decides to return home through the back roads. He needs to talk to his parents about money. He makes a little income working for PYALARA but he also works construction and plucks chickens for $1.25 an hour: He thinks his record is 250 in a day. Before the intifada and the rash of Palestinian suicide bomb attacks within Israel, he was a waiter at two hotels in Jerusalem.

There are other people on the path today, mostly old women carrying groceries and young men trying to get to Ramallah for work. The heat is intense and the only shade on the entire route is from a 20-foot wall around an Israeli settlement.

Ayysh said he does not hate the Israelis, only the soldiers, and desires peace for them too. But peace is hard to come by here.

We arrive at his home after two hours of walking and five rides in "Fords," packed minivans that seem to be held together only with chicken wire and determination. There are six people living in his family's one-bedroom house, and even more children from the area dart in and out of the family's olive trees.

Ayysh pulls out a document that he says is his most prized possession. It is a certificate of completion from PYALARA. As he stares at it the same pride that filled his face when he pointed out his village appears again. Here is something tangible that proves he has accomplished something -- fancy signatures, stamps and all.

He tucks the certificate back into its folder and we begin the walk back to Ar-Ram, where he has decided to stay with friends more permanently. As the oldest son living at home, it was a tough decision to leave his family, but the journey has become too much of a struggle for now, he says.

"When this is all over I will drive on this road," he says as we cross a road reserved for Israeli settlers. "I will no longer walk with these dirty shoes to my house."

Shares