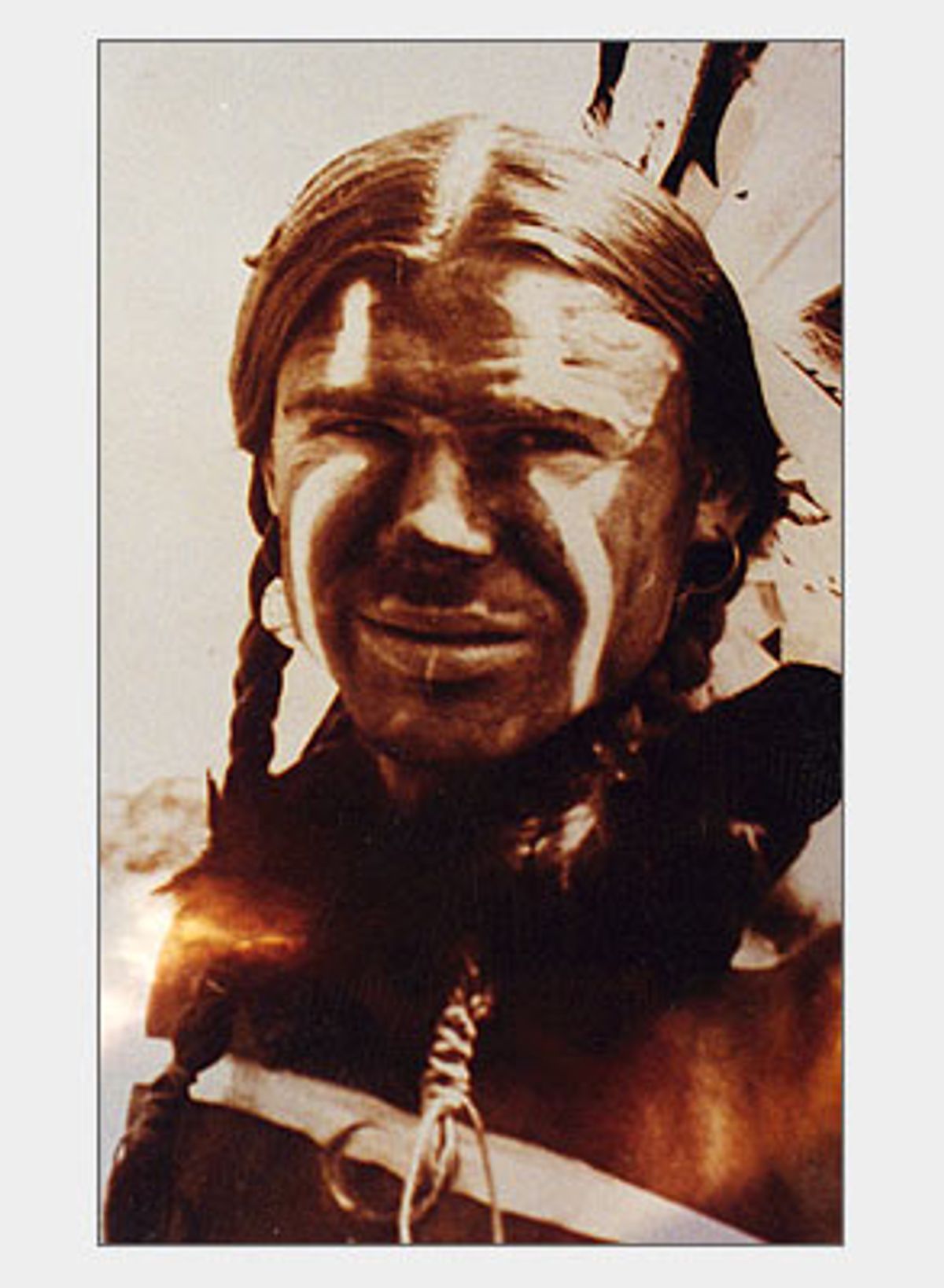

Alex Biber's day job is designing semiconductor technology. Away from work, he becomes Beaver, a Cheyenne warrior.

Biber the engineer drives on the autobahn and wears blue jeans. Beaver the brave wears hand-tanned buckskin and rides a horse, commanding the steed in an ancient language once used by Plains Indians. Biber, his wife and two daughters live in a 91-year-old farmhouse, but the family vacations in tepee villages in humid Central European forests.

While Germans may scoff at George Bush, they have an abiding fascination with the first Americans. In fact, if beadwork, horsemanship, tepee building and traditional dancing were Olympic sports, the German team would be medal contenders. Biber would likely be one of the team captains. The soft-spoken, blue-eyed man is one of Germany's weekend warriors, a tribe that numbers some 40,000 strong, according to hobbyist organizations.

By dressing up and living like an Indian, Biber and his compatriots are able to travel to a simpler time, far away from Germany, where 80 million people are crammed into a space the size of Montana. During summertime Indian camps, men wearing breechcloths have contests of strength, women prepare meals from dried meat, and bonfires crackle long into the damp night.

"I feel at home there," Biber said. "It is exactly the way it once was."

German Indian enthusiasts, known as "hobbyists," are so dedicated to authenticity that some real American Indians have approached them seeking information about their own culture. In fact, some dying Indian languages may end up being preserved by German hobbyists. But not everything is peaceful under the ersatz tepees. Some hobbyists have gone beyond the mere trappings of Indian life and have copied sacred ceremonies, angering Indians. And in a ludicrous twist, some literal-minded hobbyists have criticized actual Indians for not living up to their idealized image as ecologically aware noble savages.

At a recent powwow in Germany, for example, make-believe Indians shouted complaints about the visiting American Indian dancers' use of microphones and brightly colored feathers. The hobbyists were also annoyed that the dancers wore underwear beneath their breechcloths. The dumbfounded guest dancers protested the protests. The hobbyists lost the battle. They were kicked out and told not to return without open minds and underwear, said Carmen Kwasny, a full-blooded German and the press secretary for the Native American Association of Germany, which hosts dance gatherings near a large U.S. military base in Kaiserslautern.

"As long as [the hobbyists] stay in their little camps, we don't worry about them, but the problem is, they go into schools and get interviewed on television and they show up at our powwows and create trouble," Kwasny said.

The Native American Association's Web site now includes a list of powwow protocol. "Native Americans do not appreciate you or your children showing up in fake Indian outfits," state the guidelines. "Toy guns, plastic spears, and tomahawks should also be left at home."

"During a powwow, you will have opportunities to participate in the dancing. Please watch out for the other dancers. Do not touch their regalia."

If hobbyists insist on appearing in breechcloths, they are asked to wear shorts or cycling pants underneath.

The sizable German new-age movement has adopted aspects from traditional Lakota spirituality, Kwasny said. There are weekend vision quests with people searching for their power animals. When the animal is revealed, its image is drawn on a drum or a rattle for use in meditation. "Of course, the power animals are always wolves, buffalos, eagles, which are not very common here. They never use an ant or something like that," Kwasny said.

The Native American Association of Germany was started nearly 10 years ago to provide fellowship for American Indian soldiers stationed in Germany and to facilitate cultural exchanges. The group is spending more and more time, however, trying to help hobbyists separate fact from fiction, Kwasny said.

"People are overdoing it," she said. "They are acting like Native American people have solutions for all our problems. They need to learn to accept Indians as human beings."

Many Germans dream of traveling to the American frontier to see "real Indians," but their romantic notions are often far from the reality of life on a modern reservation, Kwasny said, recalling her first encounter with an American Indian. The free-flowing humor and jokes were especially uncomfortable for her, she said. "They were teasing me and they had a big party with plastic forks and knives. I was so shocked. I thought they were all so environmentally conscious."

American Indians can be equally surprised when they encounter blue-eyed Germans wearing war bonnets.

Ben Cloud, a Crow sun-dance leader and a member of the Montana-based tribal legislature, was skeptical the first time he was invited to visit hobbyists in Germany. He was particularly concerned when he spotted a sweat lodge in one member's yard. Sweat lodges are central places of worship for many in the Crow Nation and their construction and maintenance are guided by sacred tradition. Though Cloud was dismayed at first, he learned the lodge had been properly built by another American Indian and was being used in a manner Cloud considered acceptable.

"It was unbelievable," he said. "I was so impressed by them, the way they took care of the lodge. It was good to see that. They really respect the Native way."

German fascination with the first Americans stretches back decades, and generations of children have grown up playing cowboys and Indians.

Steven Remy, an author and assistant professor of German history at the City University of New York in Brooklyn, attributes the fascination with Indians in part to German obsession with all things American. "Historically, many Germans have been captivated by American culture, from the lore of the West to jazz to modern methods of production," said Remy. "But there's also a more ominous explanation. I think it represents the long-standing German fascination with and fear of frontiers. There may be a parallel between the conquest of the West and its sometimes violent clash of cultures and Germany's drive for expansion and a 'new order' in the first half of the 20th century."

German obsession with the American frontier exploded in 1896 when huge crowds were drawn to Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, which toured Europe. At about the same time, an eccentric German schoolteacher wrote a series of pulp novels about the exploits of Winnetou and Old Shatterhand. The Apache warrior and his German frontiersman blood-brother roamed the Great Plains fighting bears, rattlesnakes and the injustices of land-hungry pioneers. The author, Karl May, penned some of his work while in prison for fraud and never visited the West. Although the details are often comical (Apaches living in pueblos?), more than 100 million copies of his books have been sold, according to the Karl May Museum. His fans included Adolf Hitler, Herman Hesse and Albert Einstein. The characters are still so popular that some Germans name their children Winnetou.

Indian hobbyist groups began forming in Germany during the 1920s. They copied Indian dancers in German circuses and studied museums well stocked with artifacts from Montana and Dakota tribes. Many of the items date back to the 1830s, when Prince Maximilian of Wied explored the High Plains.

Biber represents a particular faction of Germans who love Indians. On a recent afternoon at his home in the south German countryside, he agreed to talk about his passion. But first, he wanted to make some things clear. Not all hobbyists are alike. Some dress up in garish war bonnets once a year to dance around tom-toms and whoop like Hollywood clichés. Others seek enlightenment through chanting, sweating and chasing visions. The serious hobbyists, himself included, take great pains to be sensitive to the cultures they copy, which is a sign of respect, he said. Serious hobbyists also know better than to conduct traditional spiritual ceremonies, Biber added.

Not all Indians interest the Germans. Most hobbyists focus on the American Indian culture of pre-1880, when the last tribes were forced onto reservations. Biber rejects the criticism that hobbyists need to be more concerned with contemporary Indian issues, such as widespread poverty or the fight to protect wild bison in Yellowstone National Park.

"What we do has nothing to do with the Indians today," he said. "What we do has to do with a culture that is already gone, like the Romans. It's not necessary for me to go to Rome and get permission to study the Romans."

Gothic monasteries and crumbling castles dot the hills surrounding Biber's home. But a slice of Indian country exists inside Biber's front gate. Among the lettuce, radishes and gladioluses in his garden grow sweetgrass and sage. Two horses bearing Lakota names -- Itampi and Sapaska -- munch grass in a stable behind Biber's home. In his barn sit stacks of hand-peeled tepee poles and a wooden travois.

Biber's daughters -- Buffalo Robe, 4, and 6-year-old Winona -- play nearby. The girls are known to their friends as Anna and Maria. These "civilian" names were given in case they outgrow the hobby, Biber said. "Many children do when they hit the awkward teenage years."

In his kitchen, Biber proudly placed a pair of moccasins and a beaded pouch atop the wooden dining table. The leather was tanned by hand with traditional brain-tanning techniques, he explained. Deer tendons were transformed into sinew to join the leather. The beads adorning the pouch are antique glass. The moccasins are covered by an ancient porcupine-quill pattern. The quills themselves were dyed by Biber's wife, Kathleen, who uses plants to make her own dyes. The pouch holds a flint and steel -- during Biber's annual Buffalo Days Camp, matches are strictly verboten.

"We also do not eat chips and drink Coca-Cola. We drink water and eat dried meat and foods," he said.

Biber, who perfected his obsessive search for authenticity over 30 years, now believes his work could fool a modern-day ethnographer, not to mention Sitting Bull or Crazy Horse.

Apart from a short phase with the Crow Nation, most of Biber's focus has been on the Lakota. This is true for a majority of German hobbyists, he said. The Lakota are the Indians most often portrayed in the German western films from the 1950s and '60s. Germans also associate the Lakota with vast grasslands, dangerous buffalo hunts, sun dances, smoke-filled tepees, eagle-feather war bonnets and midnight horse raids. And like the German language, Lakota is filled with hissing and throat-clearing sounds. "It's not so hard for us to speak it," he said.

In recent years, Biber's interest has shifted toward the Northern Cheyenne. They are natural allies to the Lakota, he explained, and their beadwork patterns and traditional handicrafts are dictated by strict family traditions. The patterns today are similar to those of 200 years ago. The Crow, Lakota and Northern Cheyenne now live on reservations in present-day Montana and South Dakota.

"The Cheyenne stuff is even nicer than the Lakota stuff," Biber said. "Excellent workmanship is something very close to Germany."

Stories like this amuse and flatter Dick Littlebear, a member of the Northern Cheyenne Nation and the president of Chief Dull Knife College in Lame Deer, Mont. So long as the hobbyists avoid copying the sacred ceremonies of his tribe, Littlebear said he doesn't worry about Germans fixating on his culture.

The hobbyists might not know it, he said, but their attention to detail could help the tribe someday. As Indian elders die off and ancient languages fade, so, too, dies unrecorded knowledge. Littlebear, who holds a doctoral degree in linguistics, said he once met a group of German hobbyists who were able to teach him lost Northern Cheyenne stitching methods from the 1850s. "They know more than we do about some of these things," he said.

If anything, Littlebear would like the Germans to spend even more time on their interest -- by attending one of the Northern Cheyenne's annual language-instruction camps, for example. Young people no longer seem to care about learning the original tongue, Littlebear said.

"Maybe 50 years from now, if things change, a Cheyenne could go over to Germany and relearn our own language," Littlebear said.

Why has the German fascination with Native Americans endured?

"It's impossible for me to answer that," Biber said. "For me, I guess, it's mostly because of their art. For many others, they have the dream of riding a horse on the prairie with the wind in their hair.

"Indians are really cool, I guess."

Kathleen Biber shares her husband's enthusiasm for the old culture, but concedes that the Indian way can be hard and sleeping on the ground during the family's annual outings is no picnic.

"I really love my bed when I come home," she said. "But I miss my refrigerator the most. You have no idea how hard life is without a refrigerator."

Shares