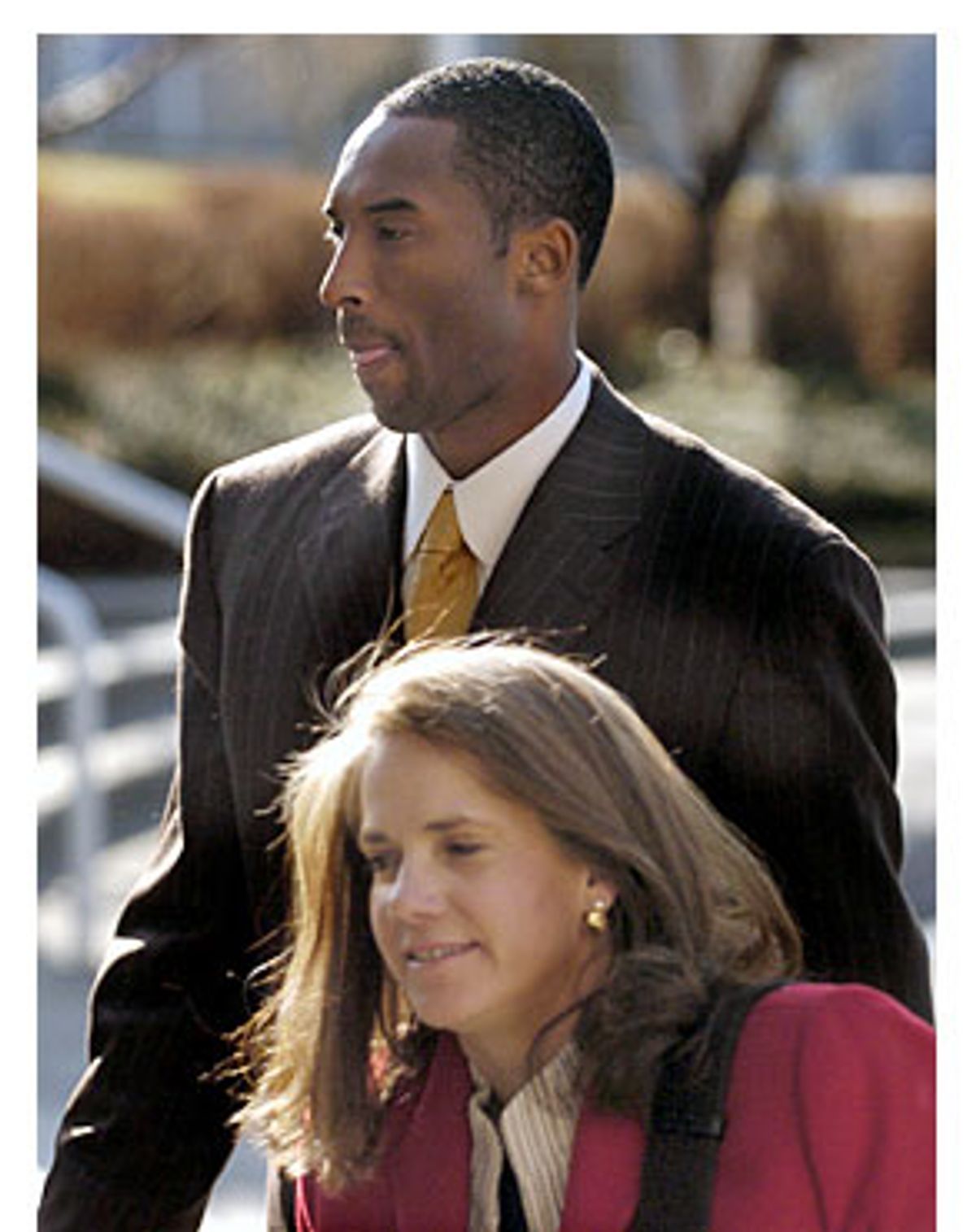

On Wednesday, the 19-year-old woman who accuses basketball star Kobe Bryant of raping her took the stand at a pretrial hearing in the Eagle County, Colo., courthouse. Apart from the usual explosive mix of sex and celebrity, the case has also generated heated debate about the rape shield laws that protect the accuser's sexual history. The purpose of the closed-door hearing was to determine what, if any, parts of this history could be admitted into evidence at the trial.

The tactics of Bryant's defense team, which has demanded access to the young woman's mental health records and suggested that she had sex with three different partners in the days before and after the alleged rape, have been roundly deplored by feminists and victims' rights advocates. In New York Newsday, writer Lorraine Dusky has slammed defense attorney Pamela Mackey for "amoral antics." Wendy Murphy, a former sex crimes prosecutor who teaches at the New England School of Law and appears regularly on television, charges that the defense has exploited misogynistic myths about rape accusers -- "that women are mentally ill, and vindictive, and lie for sport."

But the reality is much more complicated. The Bryant case is only the latest example of the conflict between protections for rape victims and the constitutional rights of defendants -- and a reminder of how excruciatingly difficult it can be to find a fair balance between the two.

There is no question that until the feminist rape law reform movement came along in the 1970s, the treatment of women in rape cases was often shameful. Just 30 years ago, evidence of the accuser's "unchaste character" (extramarital relationships, the use of birth control, the habit of going to bars alone) could be introduced in a trial with the explicit goal of impeaching her testimony. Jurors were specifically instructed to consider such evidence in assessing the woman's credibility and the probability of consent -- on the charming theory that if she was a slut, she was also likely to be a liar and probably wouldn't say no to any man.

By 1980, 46 states had instituted rape shield laws making the accuser's prior sexual activity generally inadmissible in a sexual assault trial; today, such laws are virtually universal. However, they allow for certain exceptions -- such as the woman's past relationship with the defendant, or evidence that a sexually transmitted disease alleged to have resulted from the rape may have been due to consensual sex with someone else. In many states, other evidence may be admitted at the judge's discretion "in the interests of justice," though the burden is generally on the defense to show that its relevance outweighs the negative effects on the accuser. Likewise, the courts can sometimes admit into evidence the accuser's medical history, including mental illness and drug abuse (which is protected by medical confidentiality laws rather than rape shield statutes).

In high-profile cases such as Kobe Bryant's, the use of compromising personal information about the alleged victim invariably causes an outcry about "nuts and sluts" defense tactics (a term coined some years ago by legal scholar Susan Estrich). Victims' advocates warn that rape shield laws are being eviscerated and that women will be discouraged from reporting sexual assaults. These are legitimate concerns, to be sure. Yet in some of these controversial cases, it seems clear that excluding the evidence in question would have been egregiously unfair to the defendant.

In 1991, a Maryland real estate agent named Gary Hart (no relation to the politician) was accused of raping a waitress he had been dating. The woman claimed that their relationship had been platonic, and that Hart had attacked her while she was staying overnight at his apartment. Hart claimed that they had been sexually involved, and that the woman had gotten angry because he refused to take her along on a trip. The defense was able to bring in evidence that Hart's accuser had a history of emotional instability, had made several false claims of sexual assault to psychiatrists and police, and had on several occasions reacted to romantic rejection with outbursts of violent rage. Hart was acquitted.

The trial received extensive local coverage, and the use of the alleged victim's troubled personal history in the courtroom was widely treated as if it were a gratuitous smear. A letter published in the Baltimore Sun asserted that even if the woman had not been raped by Hart, she suffered "a brutal form of abuse ... inside the courtroom." This curious logic ignores the fact that if Hart did not commit rape, his accuser was guilty of a pretty brutal form of abuse toward him -- and that her reliability as a witness was key to the case.

In many other cases, the overzealous application of rape shield laws has resulted in miscarriages of justice. In a much-publicized 1998 case in New York, Columbia University graduate student Oliver Jovanovic was convicted of kidnapping and sexually abusing a Barnard College student whom he had met on the Internet. While Jovanovic claimed that the encounter involved consensual bondage, the trial judge ruled that the defense could not use e-mail messages in which the young woman had told him about her interest in sadomasochism and her S/M relationship with another man. Jovanovic was sentenced to 15 years in prison. His conviction was eventually overturned by an appellate court that held he was denied the chance to present an adequate defense -- a ruling predictably deplored by feminist activists as a blow to victims.

And then there are the more obscure cases:

At the trial, the defense attorney questioned the woman about the fact that the morning after the alleged rape, she did not say anything about it to clinic staff members. The woman claimed that she was too embarrassed to talk about it; the prosecutor picked up on this point in his summation, scoffing that the defense expected a rape victim to "just walk up to one of the staff" and discuss "those most intimate details." But there was something the jury didn't know: The day before, she had discussed equally "intimate details" -- an alleged earlier rape and childhood sexual abuse -- with one of the clinic counselors. The jurors never heard the counselor testify about this and never saw his notes, which contained the comment that "client ... has a lot of other issues around incest/rape," because all information about the woman's sexual history had been ruled inadmissible.

None of those possible motives could be introduced at Steadman's trial: The alleged victim's legal problems were related to her past sexual activities and hence inadmissible. Steadman was convicted and given an eight-year prison sentence.

Like many such cases, the Kobe Bryant case is primarily a "he said, she said" matter, with ambiguous corroborating evidence that county judge Frederick Gannett characterized as weak even as he sent the case to trial. The woman's sexual activities prior to the alleged rape may well be relevant to the physical evidence; if, as the defense has hinted, she engaged in consensual sex shortly after her encounter with Bryant, it may well be relevant to the question of whether she was raped; if she is mentally unstable, it may well be relevant to her credibility.

These are wrenching questions. Obviously, a woman with a history of mental illness or substance abuse could still be a rape victim. Obviously, the prospect of having embarrassing personal details exposed in court (let alone paraded in the media) may discourage victims from coming forward. Just as obviously, suppressing relevant evidence may result in sending an innocent person to jail. And if it's frightening to put oneself in the place of a sexual assault victim who finds herself on trial in the courtroom, it is no less terrifying to imagine that you -- or your husband or brother or son -- could be accused of rape and denied access to evidence that could exonerate him.

For some feminists, the dogma that "women never lie" means that there is, for all intents and purposes, no presumption of innocence for the defendant. After the 1997 trial of sportscaster Marv Albert, defending the judge's decision to admit compromising information about Albert's sexual past but not about his accuser's, attorney Gloria Allred decried "the notion that there's some sort of moral equivalency between the defendant and the victim" -- forgetting that as long as the defendant hasn't been convicted, he and his accuser are indeed moral equals in the eyes of the law. Wendy Murphy has blasted Kobe Bryant's attorneys for feeding uncorroborated rumors about the alleged victim to the media maw. Yet, appearing on Fox News, she made the claim, highly prejudicial to Bryant and so far untested in a court of law, that the woman "suffered pretty terrible injuries" the likes of which she had not seen despite having prosecuted "hundreds of sex crimes cases."

In a law review article published in 1977, when rape shield laws were being adopted across the country, Columbia University law professor Vivian Berger, generally a supporter of feminist law reforms, cautioned against "sacrificing legitimate rights of the accused person on the altar of Women's Liberation." Twenty-seven years later, we are still grappling with this issue, and Berger's warning remains as timely as ever.

Shares