A lot of people bent over backward last week to treat musician Patti Scialfa, traveling the talk show circuit flogging her record "23rd Street Lullaby," as if she were any other rock chick with an album to sell. In a particularly understated moment, "Today Show" host Matt Lauer thanked her profusely for signing a guitar for charity, and then -- practically on cat's paws -- added, "I want to mention, just very much in passing, that her husband, Bruce, is here and has also agreed to sign the guitar ... so that name will be on it as well." When Scialfa performed on "Late Night With Conan O'Brien," O'Brien neglected to point out that his musical guest had spent significant periods of the past two decades recording and touring with in-house drummer Max Weinberg. And on "CBS Sunday Morning," host Charles Osgood previewed a profile of Scialfa by saying, "She's musician Patti Scialfa, playing her music. He's her husband. Meet them both next Sunday morning."

They were all shimmying -- carefully, respectfully, awkwardly -- around the elephant in the room: you know, the one with the best ass in rock 'n' roll? It wasn't until Scialfa hit "The View," and co-host Meredith Viera asked, "You chose music that is pre-Bruce and the E Street Band, pre-kids and marriage ... Why?" that anyone got to the heart of what exactly was interesting about "23rd Street Lullaby," Scialfa's first solo outing in 11 years.

Scialfa, a former busker, bar singer, waitress, backup crooner, and a longtime member of the E Street Band, is mostly known as Bruce Springsteen's wife of 13 years -- or as he calls her at his concerts, the "First Lady of Love." But now, during a summer when her husband has not taken to the road for one of his earthquaking, ass-shaking, moneymaking tours, the most envied wife in rock 'n' roll has released an album that extols the joys of a life alone in New York City -- and the days when she was no one's first lady but her own.

"That time in my life was a very formative time for my music," Scialfa replied to Viera's question, emphasizing the word "music" as if to underscore the point that, yes, she was a professional musician before she shook a tambourine in the "Glory Days" video. "It was a beautiful time; it was very rich and vivid, so I wanted to go back and express that part of myself."

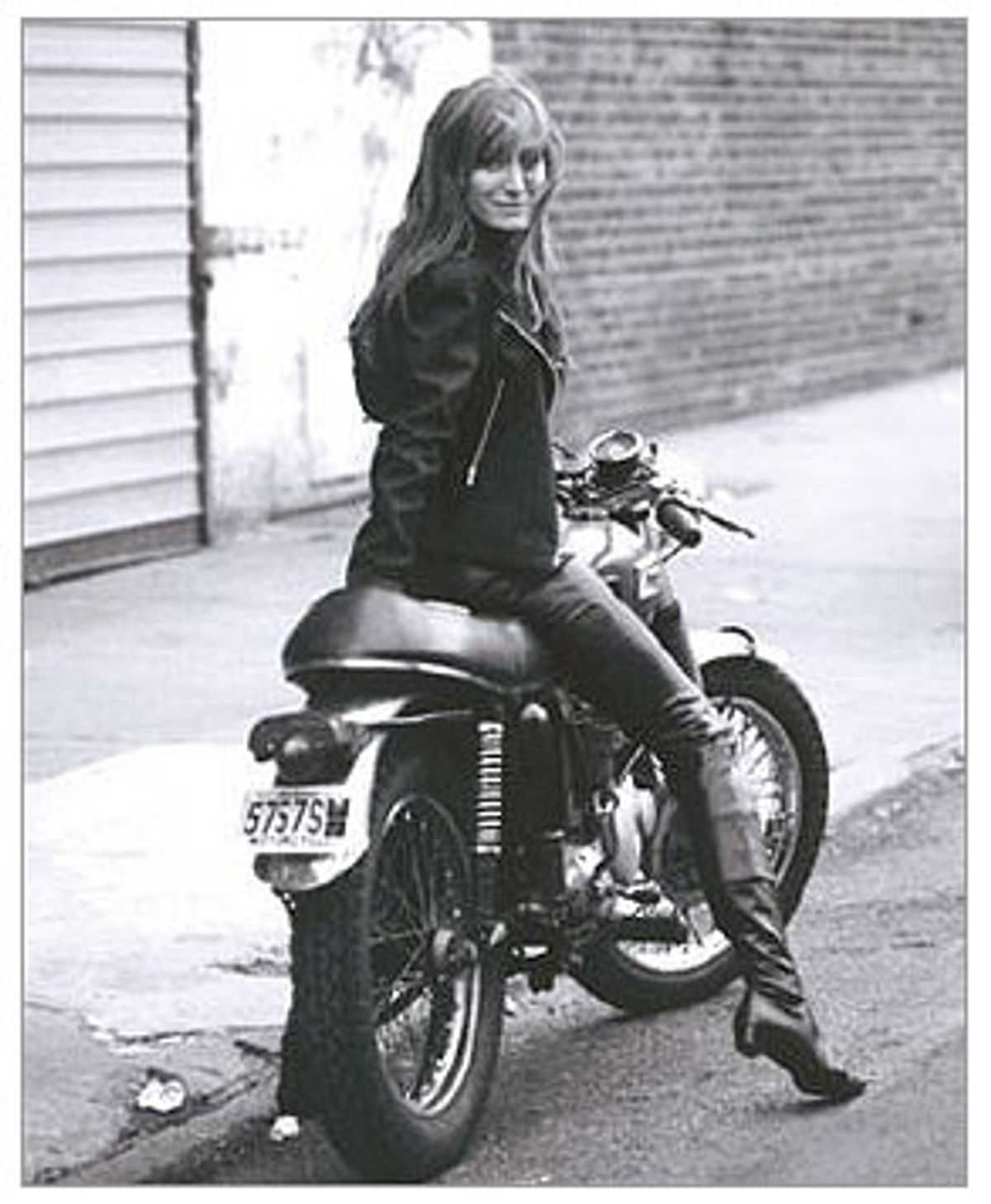

She expresses that part of herself in song and on the liner notes for her new CD, which feature an image from her high school yearbook that lists her as "Vivienne Scialfa," pictures of '70s Patti with shanks of limp hair falling around her face, '80s Patti with leggings and lacy collars and big hair, braless Patti with Urban Cowboy hat and curls. "This record was a way of giving myself some autonomy," she told "CBS Sunday Morning's" Jim Axelrod. "This is my past, this is who I am, this is where I came from."

Scialfa came from Deal, N.J., or, as CBS's otherwise perceptive interview put it, "Where else but the Jersey Shore?" -- as if by entering the world in 1953 mere miles from the Garden State's coastline, Scialfa had already seen the future of rock 'n' roll and was doing everything in her embryonic power to make sure she would make a suitable mother to its children.

But she didn't even lay eyes on Springsteen for her first 30 years. Scialfa started singing in bars in New Jersey in high school, and studied at the University of Miami's jazz conservatory before transferring to New York University. She spent 15-odd years in New York: waitressing, backing up acts like the Rolling Stones and David Johannsen, trying to score a record deal of her own, and singing on the streets with Soozie Tyrell, the fiddler who now performs with the E Street Band and is featured prominently on "23rd Street Lullaby." Scialfa lived in Chelsea and zipped back and forth to Asbury Park, where she would perform at the legendary Stone Pony.

It was there that she met Springsteen in 1984. On "CBS Sunday Morning," Springsteen recalled that the first time he heard her sing, he thought of Dusty Springfield and Ronnie Spector, but that she "had something of her own that was going." He asked her to become the first woman in his band, and she traveled with them on the mammoth "Born in the USA" tour, a redheaded, angular counterpoint to the low-to-the-ground weirdness of guitarist Steven Van Zandt and the larger-than-life saxophonist Clarence Clemons. Legend has it that Scialfa fell in love with Springsteen on sight, but in 1985 he married model-actress Julianne Phillips, and Scialfa returned to Chelsea. In 1987, Springsteen asked her to tour again for "Tunnel of Love," the album that chronicled his ailing marriage. In 1988, photographers snapped Springsteen and Scialfa scantily clad on a Rome rooftop; in 1989 his divorce from Phillips became final; in 1990 Scialfa and Springsteen's first son was born; a year later the two married; in 1993 Scialfa released her first album, "Rumble Doll," but didn't promote it heavily because she was pregnant with her third child.

See how those 15 years in New York seem to melt once you get to the second half of the story? Whatever thing of her own Scialfa had going back at the Stone Pony got hijacked -- happily, perhaps -- by a band, by Bruce, by babies. On "23rd Street Lullaby" she's returning to the realm of the single girl -- lonely, freaked out, proud of herself for getting by, and wholly consumed by her work and by the city in which she is carving out her identity.

In the album's title track, which moves from grating to addictive in no time, Scialfa sings from a place of comfort -- but it's a place I recognize, which means it has nothing to do with family or stability. Singing that she's "a little low on courage ... but high on faith," Scialfa is soothed by the "bass and drums and the traffic hums" of her own neighborhood. Her comforts aren't lovers, they're her music and New York -- the city that Carrie Bradshaw would tell you is the best boyfriend in the world. Scialfa's promise that she's "got a bottle of wine, a bag of tricks" and "a place for you under my fingertips" is a gentle bit of eroticism, but could be aimed at her guitar as easily as at a man. She's in love with herself and the way she's making her living.

If we're lucky, we get that when we're single: a period in the midst of bad boyfriends, of not knowing whether it all ends up OK, of anxiety about money and friends and identity, when suddenly we're at peace and can feel ourselves propelled forward. It's when all the self-absorption becomes the fuel on which we ride our careers and independence as far as they go before they get stalled by families or mortgages. It can be an absolutely gorgeous, selfish, powerful moment for women -- and as liltingly serene as Scialfa's "Lullaby." But sometimes -- often, in fact -- that same period of rootlessness really blows.

Just listen to "Romeo," a track that may or may not be about Springsteen. (It would be lovely to think that it's not. After all, her husband has loved his Marys, Janies, Candys, Wendys, and Sandys for so long, it would be nice to know whom Scialfa loved ... before.) But her decision to bookend the liner-note lyrics of "Romeo" with a photo of herself in a wedding dress and the only photograph of Springsteen on the CD suggests that the song could be about those ugly years he spent married to another woman. Or maybe Romeo is a figment of her imagination. In any case, she's mourning a man who's left her. "You're part of me forever/ Like a troublesome tattoo," sings Scialfa. Curled up "in someone else's arms" in Chelsea, she tortures herself over the guy: "I believe in heaven above/ And when I look in your eyes/ I believe I still see love/ Well maybe I will never know/ Just why you walked away/ Did you think I wasn't good enough?/ Or were you just afraid." Anyone who's ever spent a similar night will feel their stomach clench. Remember the soul-gobbling misery? The conviction that the only person who's right for you -- rogue, married, deluded -- has left you to a life of empty encounters with nameless, faceless, wrong people who will never know you as he did? "I lay awake at night/ Curse your name into the dark/ While the memory of you rings/ Like a church bell through my heart." For those of us still out there, the images are almost uncomfortably vivid.

It's just one of the songs on "23rd Street Lullaby" that seems as if it must have been written 20 years ago. How could a woman married for more than a decade recall that deadened feeling of hopelessness so specifically? Isn't it one of those pains that is supposed to get reabsorbed by the body -- like childbirth -- as soon as it's finished? I had hoped so.

However clear her memories -- or however long these tunes have been sitting in her notebook -- Scialfa has put some distance between herself and 23rd Street. In "You Can't Go Back," she discovers just that, after "looking for a piece of my past/ on these streets that I once knew." It's unclear whether her revelation that she will never be able to case her old haunts in anonymity again is recent, or whether it first occurred to her when the song opens, in "New York City/ 1988/ Standing in the Chelsea rain/ With a small suitcase." It was in June of 1988 that the Italian paparazzi ensured that Scialfa would never go back to her invisible city life again. It's a year that also comes up in "Rose," when she sings "Now listen ... I traveled once with this/ Rock'n'roll band/ And my baby was a hero/ At every small town bar/ And I watched that summer of '88/ Pass through the rear-view mirror/ Of his rented car." Whether or not the E Street Band was traveling via Avis is immaterial; Scialfa's interest in 1988 betrays her understanding that that was the year that gave shape not only to her future, but to her past.

A single and unsettled youth exists as a blur. You never know when or if or how it will end -- with money, romance, kids, a move? It's a period defined by its utter lack of certainty, and thus a period that is hard to define at all until something about it changes. It's in that moment of transformation -- whether it's finding love with a ridiculously hot and brilliant rock star or, you know, moving into a nicer apartment -- that whatever has come before gets thrown into focus. It takes shape and becomes more beautiful than it ever previously appeared -- precisely because it's about to end. Maybe that's what 1988 was for Scialfa, the moment that she realized that she got the guy and the life she never thought would be hers, and in doing so, cut herself off completely from whatever had been hers and hers alone in New York City.

Every harried mother and every wife must experience nostalgia for a time when she was regarded on her own terms and not in relation to someone else, even if that means revisiting the uncertainty of solitude. Scialfa's experience is just writ very, very large: live alone and struggle for 15 years; fall in love with the most famous and successful rock musician in the world; live through his agonizing marriage to another woman; become his wife and mother to his three kids and live in a gigantic house in your home state close to your entire extended family with gobs of money and a life where you get to perform for hundreds of thousands of ecstatic fans; look back fondly on the days when you were lonely and struggling.

It may be brave of Scialfa to sing about the pre-Bruce days, offering Springsteen fans precious few voyeuristic crumbs on which to feed. But it's also very smart. When asked on CBS why she doesn't write about her kids and marriage, she replied that she "finds contentment and happiness not to be a great field to work in as far as things that hold my interest." That's fair, but what she's not saying is that even if her lyrics rely on themes of hope and faith, trains, diamond snakes, and a gypsy woman who has been well employed by this couple over the years -- they do not tread on territory that Springsteen has already covered. For one thing, who would want to compete with a description of a marriage that has already been lovingly rendered in Springsteen's "Better Days?" ("Now my ass was draggin'/ When from a passin' gypsy wagon/ Your heart like a diamond shone ...") Not Scialfa. She has instead thrown her voice behind one of the only populations that Springsteen has somehow neglected to represent over the years -- my own.

Yes, he's sung about his own youthful forays into Manhattan. He talked it real loud and walked it real proud, and strutted and burst like a supernova. Springsteen's songs of his New York City days are jubilant and intense and gloriously cocky but not exactly reflective. But Scialfa's done more than get serious about singlehood -- she's winnowed out one of the few voices that Springsteen has never deployed himself. Springsteen has told the stories of immigrants, factory workers, troubadours, beach bums, police and firemen, overwrought fathers, conflicted sons, despondent husbands. And it's not as though he's been reluctant to tackle a female perspective: He's given voice to 9/11 widows on "The Rising" and to a worried black mother in "American Skin (41 Shots)." But Springsteen's young women ... well, they have generally been limited to the variety eager to strap their hands across his engines.

Fair enough. Who doesn't want to strap her hands across his engines?

But listening to Scialfa's CD made me realize that her husband -- whose music has provided a core that I've drawn on politically, intellectually, romantically and spiritually since I was a child -- has never sung songs that reflect much about the realities of my adult life. That's fine -- and a lesson in the limits of self-absorption: Happily, we love art that has nothing to do with us. I'm not suggesting that Scialfa's music is any sort of fill-in for Springsteen's; it's not supposed to be. All the same, I found myself charmed and moved by the neatness of her trick. Here was a woman about whom I've thought a lot over the years -- cheering her, envying her, wondering how she got so thin, how she got so lucky -- stepping up to the plate and pitching one straight at me.

It's a nice retort to all the Springsteen fans who have pigeonholed her in a million ways over the years, always in relation to their hero. She was a mistress; she was a Jersey girl. She was the "right wife," taking the place of the "wrong wife." She was also the woman with whom Springsteen moved to Beverly Hills after firing his beloved band. On "23rd Street Lullaby," she's simply the person she was before she started to mean so much.

Let's not pretend there aren't perks in being married to a man who eclipses you completely. It's not every 50-year-old broad who releases her first album in 11 years and gets to promote it on Letterman, Conan, "The View," "Today," the "Early Show" and "CBS Sunday Morning."

But it's not every Arkansas lawyer who gets to be the junior senator from New York, and not every fictional New Jersey housewife who has $600,000 to throw at a piece of land. That doesn't mean that Hillary Clinton isn't a good senator, that Carmela Soprano won't be a gifted developer, or that Scialfa's album doesn't merit all the attention and praise -- four stars from Rolling Stone -- that it's getting. It just means that if you're going to live in the inescapable orbit of an enormous sun, you might as well benefit from whatever heat it offers.

And as far as that burning sun goes, Scialfa's album contains what feels like a valuable lesson. "Once I watched you walk on water," she sings on the album's beautiful final song, "Young in the City." "Now I watch you walk across the room." If she's singing about her husband -- and for my purposes, she is -- then the rich suburban lady across the river has something important to say to those of us still struggling with bills we can't pay and worrying about boys we can't have. Whatever it is that shimmers in the distance for us -- that thing we long to grasp but fear we never will -- may not only find its way into our lives, but someday become mundane.

Unless, of course, that thing we long to grasp is Springsteen himself. He's already taken.

Shares