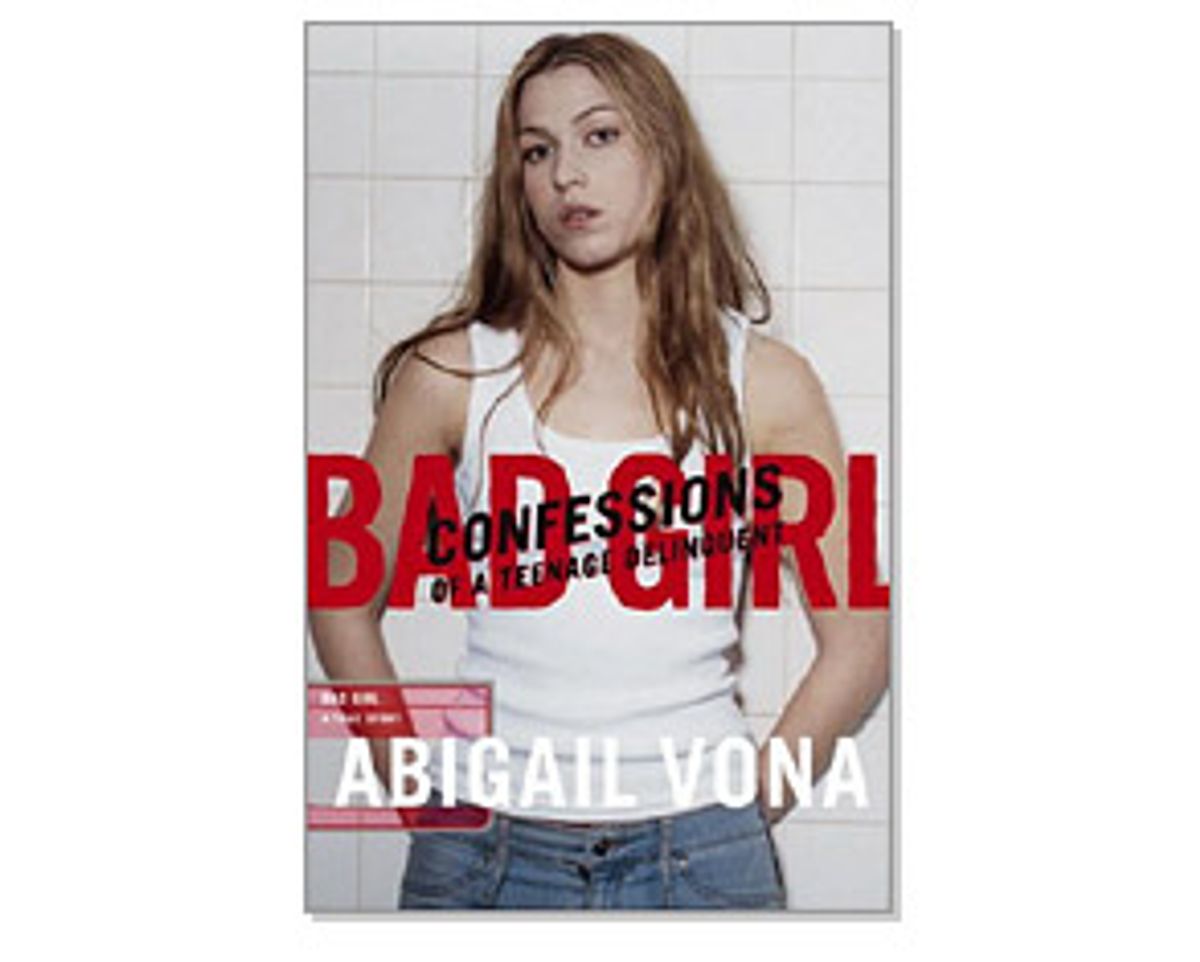

The media loves the barely legal girl with a troubled past and a memoir -- or a novel so thinly veiled you can see through it -- in hand. (See Elizabeth Wurtzel, Amy Sohn, Molly Jong-Fast). So it makes sense that Abigail Vona, the 20-year-old author of the just-released "Bad Girl: Confessions of a Teenage Delinquent," an account of her year at a Tennessee lockdown facility for delinquent teens, has received an ample amount of press already.

But it's not for her book: Instead, the attention on Vona has focused on her relationship with her ex-boyfriend and former agent, 48-year-old Doug Dechert. Two years ago, at a party in New York, Vona's aunt introduced her to Dechert, a staple at media parties and a consistent source for New York gossip columns. After hearing about the manuscript that would become "Bad Girl," Dechert offered to help Vona publish it. He introduced her to novelist Jay McInerney, who would connect Vona to her editor and publisher, Web Stone at Rugged Land Books. Dechert and Vona dated for a year, but the relationship ended badly in May -- both Dechert and Vona blame each other -- and Vona found herself the center of a New York media maelstrom. "Page Six," the New York Post's powerful gossip column, ran an item about Vona and Dechert's breakup -- an item unsympathetic to Dechert -- and in retaliation, he wrote a screed about Vona that he posted on his Web site and which was quickly picked up by Manhattan media blogs.

Dechert's piece about Vona, "Creation of a Bad Girl," claims, among other things, that Vona took advantage of Dechert to get her book published and dropped him when he was no longer of use to her. She didn't even write the book -- she dictated it to her mother, Dechert says; her editors had to completely overhaul the manuscript to make it publishable. As proof of her lack of writing skills, Dechert includes an unintelligible passage on his Web site that he attributes to Vona's "fractured prose." Oh -- and he also goes into great detail about her body and their sex life ("She had big hips and short piano legs supported by heavy calves like overstuffed sausages, but she was mine and I wanted her"), and claims she had an abortion after getting pregnant by him.

How did a teen troublemaker from suburban Connecticut end up here? Five years ago, Vona, then only 15, spent a year at a "lockdown facility" for troubled teens in Tennessee called Peninsula Village, participating in daily intensive group therapy with the drug addicts, prostitutes -- even barely teenage child molesters -- who made up her "Group." The patients were forced to do push-ups for infractions as small as dropping a food tray, and weren't allowed to watch TV or movies, read books, wear clothes from home -- or even talk to one another. (After a few months there, Vona is finally allowed some privacy from the staff and starts to amuse herself by creating shadow puppets against the wall with her hands.)

She went to Peninsula Village against her will, of course: Her father, a cardiologist, said he was sending her to "summer camp." (Vona's mother, who divorced her father when Vona was young, doesn't come up much in the book.) Throughout "Bad Girl," Vona reminds us that she didn't need to be locked up: She wasn't a prostitute or a self-mutilator, after all. She was just bad. She snuck out constantly; she had a stealing problem; she lied; she smoked pot; she dated drug dealers. But after spending a year in lockdown, she writes, she realized the source of her kleptomania, anger and aggression -- her neglectful, abusive and overly permissive parents -- and learned how to deal with her anger without lashing out.

"Bad Girl" is a short, choppy book written in a style so simple that it does, actually, read as if it's been dictated, although Vona denies that claim. And the Vona that we're introduced to through her narrative -- the girl who spends most of the memoir wondering why she's there, since she's not as "bad" as the other girls -- is different from the Vona we see through the "patient's notes" that she obtained from the Village during the book's editing process and includes throughout the book. ("Patient seems to act confused ... it is unclear at this time what is an act and what the patient just does not understand.") The therapists constantly refer to Vona as irresponsible, possibly dangerous, and generally just spacey.

While charming and warm when I met her last week in Times Square, where I spent over two hours with her at the Millennium Hotel's restaurant, I also saw a bit of what her doctors meant.

Do you feel like the recent media attention about you hasn't been focused enough on the book itself?

Of course, especially because of my agent. The piece that [Dechert] wrote was very disgusting and unnecessary and untrue and pulled out of context. The book is a positive story. People are focusing on the fact that I royally fucked up with a boyfriend.

Let's talk about how you wrote the book. What happened after you left the lockdown facility?

I wrote it. I spent two years in high school writing it. Oh, another thing he said is that I dictated it.

Did you?

No. My publisher thought it would be cool to say I dictated it because I'm dyslexic. When I came to him I had a full manuscript. [After we were done editing] he gave me the manuscript and I flipped through the pages. He'd written an author's note saying I dictated the book. It doesn't say that now; I rewrote it. It said, "I can hardly read my book." I was, like, what the fuck? [The publisher] said, "Well, Abby, people are confused because you're dyslexic. I didn't want to say that you were bad at spelling or that your grammar isn't too hot, so I just said you dictated it."

I actually spent a lot of work on it and for someone to take that away from me was fucking nerve-racking, but I didn't really want to come out and say my publisher is an asshole.

So tell me about the process of writing it.

I came out of the Village and a month or two after, I started writing it freehand. It was kind of like a diary. Then I showed it to my mom and she said that it was really good, and she liked it. It took me two years. I wasn't that dedicated to it; it was like once in a while I'd write it. And I wrote some of it in my creative writing class [in high school].

The old title was "Shallow Waters Rising," which I thought was a little less tacky than "Bad Girl." I don't like the title "Bad Girl." The publisher titled it. I was like, what a cliché, you bastard.

What made you think it would be a good story?

It's also a positive, self-help story. The way I was before I left for the Village -- I was a complete nut. I was a narcissistic girl. I wasn't looking at the whole picture. When I was writing the book, I had to keep in mind how my mind was at the time -- I was completely self-absorbed and playing the victim. It was always someone else's fault.

You weren't allowed to read or write in the lockdown, but were you thinking about writing a book about your experience while you were there?

I was actually thinking, This would make a good TV show. I'm working on a script for a TV show now. I have a new agent who wants to pitch it. It'd be like "ER" meets "Jerry Springer." You'd have the same staff members, but you'd get a new flow of kids and a new flow of issues. But it couldn't be a reality show; too many legal issues.

Being at the Village was so hard, though -- I'm surprised you started writing it immediately after your release. It seems like your instinct, as someone in an intense teen addiction/behavior recovery program, would be to look toward the future instead of wanting to relive it.

It was hard to forget. It was such a big part of my life, and it was traumatic. I think I thought about it more when I was coming out. Life [at the Village] and normal life are so different. Once I finished the book it felt like I was over with the whole thing; it was behind me. But I wanted to write about it.

Was your family supportive during the writing of the book?

My dad didn't like it. He referred to it as "pie in the sky." He just never imagined that I could get the book published.

My mom was [supportive] at first, but now she's really upset because my publisher made me add her into the book. I was purposefully very vague in the book, because that was a really hard time in her life. After I got out of the Village, I spent a summer with my dad and then went to live with my mom.

The Village didn't want you to live with your mother, because they felt she didn't discipline enough for stealing and lying.

No, she never disciplined me. She thought it was kind of amusing, until it got out of hand. But she's changed a lot and got a lot better.

At the end of your stay you were allowed to go home to see your father, but the Village was extremely strict about how you could do it. Your father was supposed to be with you at all times, but he left you alone for most of the day, and you ended up sneaking out to party with your ex-boyfriend.

When I came back from the Village I realized that my dad is very ... distant. And you can tell it when I came home; he was off doing God knows what for the day. That really showed that he wasn't exactly there.

How did you meet Dechert, who ended up being your agent and boyfriend?

My aunt introduced me to him. I was visiting her. I met him a year before we dated. I met him and he called me about my book. He said, Yeah, I'm willing to help you. And the next thing I know, he invited me to parties in New York. He was cool, just like a friend. I didn't imagine him hitting on me because I was so much younger. I felt protected.

What did you think of him when you met?

He was like no one I'd ever met. My radar is all fucked up with men. I'm trying to reorganize it. He'd call me and say, "I have a great party to go to, you should come down and bring your friends." I thought he was a friend. They were interesting parties for a Connecticut suburban girl.

A New York magazine article said that he'd attended a party instead of accompanying you to get an abortion, because you'd gotten pregnant by him. Is that true?

Oh God, I don't know if I can answer these questions ... but why not, it's out there, right? He made me look like a whore, calling me a "receptacle" for his "sperm" on his Web site. In reality, I lost my virginity to him. It was the first relationship I ever had. I'm telling the truth. I'm not lying. People from home were like, what the fuck, why are you dating this older guy? And I think I'm a little fucked up when it comes to men. I think I didn't feel secure around boys my own age. I think I wanted someone to guide me. And Doug did guide me. My parents never guided me. There was something comforting about that.

A waiter walks by, and Vona, eyeing the buffet table in the middle of the restaurant, asks if we can order brunch. The buffet is for a private party, the waiter says. "There's no extra stuff?" Vona asks, and then turns back to me.

You know ... they wouldn't know that we're not part of that party ...

Um, but wouldn't that be stealing? Aren't you supposed to be avoiding that?

It just looks so good! I'm sure they have extra ... I'm just kidding.

Well, speaking of the kleptomania -- have you stolen anything since leaving the Village?

I don't steal anymore. There was a time when I walked away with more goodie bags at a party than I should have.

I don't think that counts. What about sobriety -- have you drank or done any drugs?

I haven't had anything to drink or smoke since I left. You can test my hair.

How were the things you dealt with in therapy -- addiction, kleptomania, anger, self-loathing -- affected by your relationship?

Doug was a big relapse. I relapsed emotionally.

In the book you're dealing with so much drama, and now that life is supposed to be less intense, you're wrapped up in this gossip and media story ...

I don't know if it's me or who I'm attracted to. I think I'm just attracted to situations where I know I'm going to get fucked.

Are you still in therapy now?

I should be. I'm trying to get my shit together by attracting people who are more stable. But normal people are pretty boring.

It took me a while to really understand why I was so dependent on Doug. Partially because he was condescending to me and made me feel like I needed him, when I didn't.

When was the last time you talked to him?

Right before he put his article on the Internet. He had e-mailed it around. I called him up and said, "You realize you're not hurting me as much as you're hurting yourself, don't you?" And he said, "Well, you called me an asshole in an interview." And I said, "Ok, you are an asshole."

Do you feel hurt or upset about this? Because you keep making jokes and laughing about it ...

It's actually depressing. I've been through a lot of trauma in my life and you have to joke about trauma, or else it will consume you. But it's very painful that he wrote that. I haven't read the whole thing. I can't read it. It's disgusting. I couldn't read the New York magazine story either. She also portrayed me as using him, but that's what he wants. I just hoped no one read it. I have lawyers who want to sue him.

So you're thinking about suing him.

I'll have to. I don't know what else to do. I mean, I'm hurt too. A lot of what he said is factual -- I mean, I did go to parties with him -- but it was the angle he took. I'm fucked up, and I admit I'm fucked up, but I'm not a social climber or a slut.

In his screed against you, as part of his evidence that you didn't write the book, he says you asked him to do your homework for you.

Yeah, I did ask him to write a paper for me. I was pressed for time. I was going to school and he was like, I'm the writer. I'm the one who's good with spelling and grammar. But I'm more of a storyteller than a writer, I think.

Are you at all glad you were sent to the Village? Do you think your parents were right to do it?

They had good intentions, and they wanted to help, but I was in a position where the Village wasn't absolutely necessary. But I'm grateful to my parents, because I didn't really learn what I needed to learn from them. And I learned a lot from the experience -- how to handle bad emotions. The most valuable lesson I learned was that people are flawed. They're not all bad or all good. And for the most part, if someone's acting up, it's usually because they're hurt. Scarred people lash out in ways that are hurtful to others.

Considering all that's happened since you published the book, are you glad it's out there, or do you wish you'd never written it?

Sometimes. I just want [Dechert] to disappear. I feel like I'm in a horror movie and he's Chucky or something. Chucky always returns. You think you keep killing him, but he keeps coming back.

If I hadn't dealt with the lockdown facility I don't think I'd be able to deal with this. But everything seems like a breeze compared to being at the Village and eating this nasty Southern food. Even my shower time was only two minutes long. It made me not take everything for granted. So the media writing stupid shit? That's child's play. Shit, nothing is worse being locked up in the Special Treatment Unit.

Shares