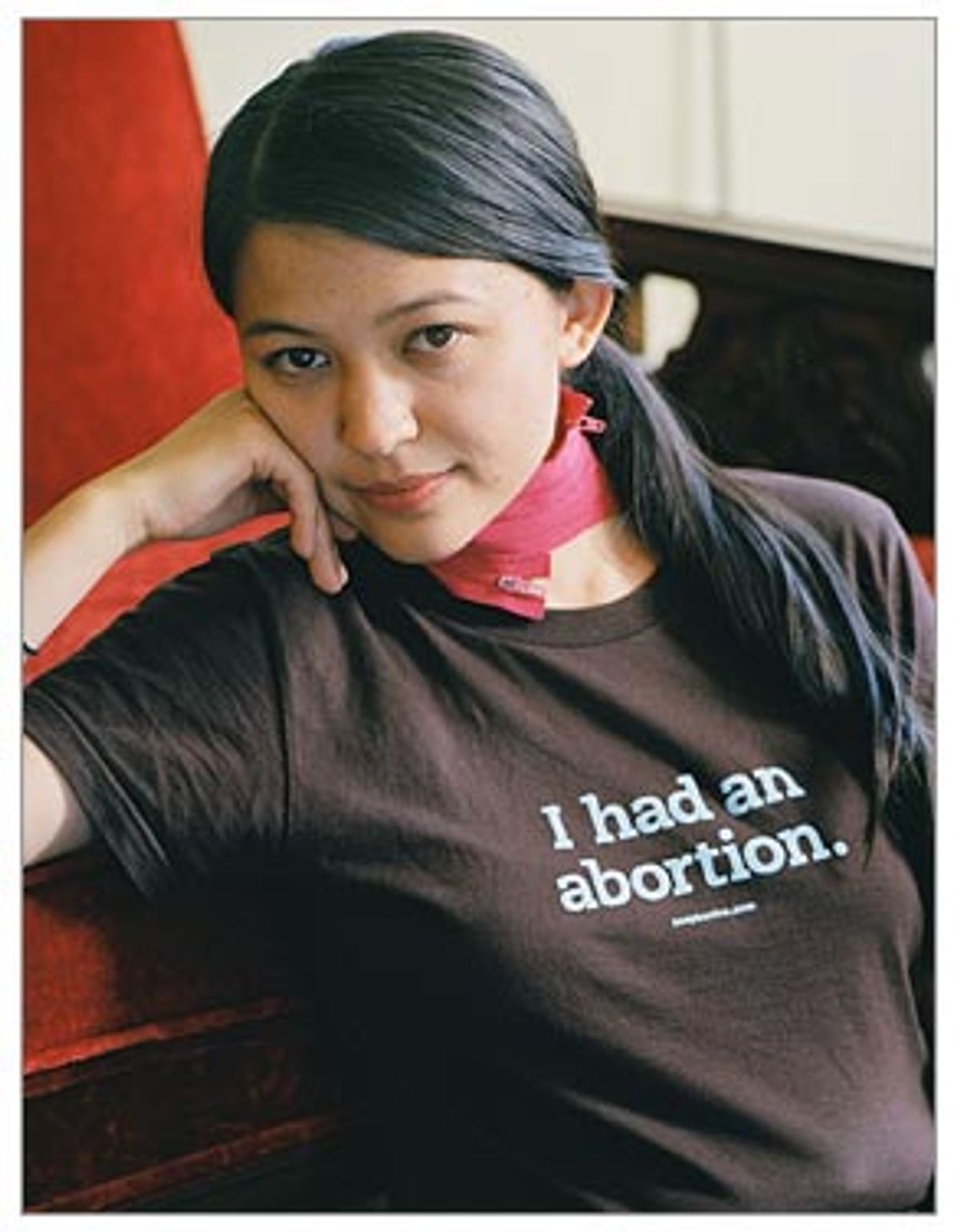

"It was the safest place, but I felt vulnerable," admits 34-year-old author and "professional feminist" Jennifer Baumgardner, between bites of panini at an East Village cafe, in New York. She is referring to the sole occasion -- April's March for Women's Lives in Washington -- on which she wore one of her controversial T-shirts, which read, simply, "I had an abortion." Eight months pregnant, Baumgardner mentions the piles of hate mail she has received since producing the tees, and half-jokingly whispers about a fear of getting shot.

Baumgardner, who created the shirts in 2003 when she began work on a film also called "I Had an Abortion," insists that she didn't design them for shock value, but to spark discussion about abortion and help "personalize" the still-taboo subject.

Still, why would anyone advertise something so personal? "To destigmatize what's still known as the A-word," says Jane Bovard, 61, president of the National Coalition of Abortion Providers, who with her staff at the Red River Women's Clinic, in Fargo, N.D, have "once or twice" sported the shirts en masse to after-work happy hour. "No one has said anything at all," Bovard notes. (Not everyone is so tolerant of the shirts; when singer Ani DiFranco donned one in Inc., the magazine received several angry letters and lost some subscribers.)

To Baumgardner, who has sold 600 shirts out of her apartment and through Planned Parenthood, the tees represent "a new arm of the pro-choice movement" in which women "own up" to their abortions, talking about them candidly without shame or remorse. Not that talking about abortion rights is anything new. "Women telling their stories has long been a [pro-choice] tactic, but the difference is that right now there's a lot of activity, enthusiasm and political energy behind it, so it's especially vibrant."

While the message isn't that different from the consciousness-raising of the '70s, the medium has changed. In the past few years, a growing group of women have connected with each other -- in hopes of changing cultural attitudes -- by creating Web sites (I'mNotSorry.net, the Abortion Conversation Project, I Had an Abortion), fanzines (Mine, Our Truths) and movies (Penny Lane's "The Abortion Diaries," and Baumgardner's film) that frankly describe their abortions, and their range of emotions afterward.

In "I Had an Abortion," Baumgardner's hourlong documentary, 20 women (including Gloria Steinem and Byllye Avery of the Black Women's Health Imperative) frankly detail their decisions. According to Baumgardner, "both [Steinem and Avery] felt relief" after their abortions. Steinem got pregnant right after college. She knew if she kept the child, she would have to marry the father, and, Baumgardner says, "Her life would be subsumed by his. The doctor who [performed] the procedure made her promise to do something great with her life. She tried for a couple of years to feel guilt on the anniversary of the abortion, but she never did."

Avery was a widow and a mother of two when she had her abortion in 1973. She, too, never felt guilty about the decision. Instead, she saw it as "the absolute right thing," Baumgardner says, "a commitment to the children [she] already had."

Filmed by Gillian Aldrich, a field producer for "Bowling for Columbine," Baumgardner's documentary will begin screening in January to mark the 31st anniversary of Roe vs. Wade. She describes the project as "a consciousness-raising tool" in which she presents a historical overview of choice, as well as encouraging women, in their own words, to say, "'I had an abortion' and own it."

"It sounds fucked up, but having an abortion was one of the best things I ever did," says Kathleen Hanna, 35, frontwoman of New York electro-punk band Le Tigre (and formerly of the seminal Riot Grrrl band Bikini Kill). "It was one of the first things I did on my own; I worked at McDonald's, raised the money and did it. I'm really, really passionate about pro-choice, because I wouldn't be here talking to you right now if I'd had a kid at 15."

A longtime activist, Hanna embraces the notion of women talking openly about their abortions. But she hopes it leads to political momentum, not just "people sitting in a room talking about their lives ... which is great, but let's change legislation so that Roe vs. Wade can never get overturned."

Melinda Gallagher, 31, co-founder of women's sexual entertainment company CAKE, agrees. "If we elect him again, we're going to see an assault on Roe vs. Wade as a constitutional right," Gallagher says, not deigning to utter President "Him's" name. "I don't think they'll go straight for Roe vs. Wade; they'll just chip and chip and chip at our rights, until abortion has to be performed within the first three days of pregnancy. Denying [the reality of abortion] is denying the experience of millions. Not talking about it is antiquated."

But is simple story-sharing a cogent starting point for social change? Baumgardner, author of the soon-to-be-published book "Grassroots: A Field Guide to Feminist Activism," with Amy Richards, certainly thinks so. "Starting from Margaret Sanger, there's a connection between women telling the truth about abortion and laws changing. If more women are honest about their abortions, it will be harder to take away that right."

This new breed of storytelling is, in classic women's studies 101 fashion, as much about the personal as it is the political. "It's the positive experiences that are being silenced, not the negative ones," says Patricia Beninato, 38, who has published more than 200 women's accounts of their abortions on her Web site I'mNotSorry.net.

Based in Richmond, Va., Beninato launched the site in January 2003, just days after Roe vs. Wade's 30th anniversary. She was floored by the number of responses from women who, like her, had "100 percent no regrets" about their abortions. "I want to show that contrary to pro-life propaganda, most women who undergo abortions are not locking themselves in the metaphorical closet screaming about pain and guilt," she explains.

Judging from the stories on the site, Beninato is right. "Hannah," a 31-year-old cancer survivor, had an abortion the day before submitting her story to I'mNotSorry. Her planned pregnancy brought about an unexpected side effect: paralyzing depression. "I thought of throwing myself down stairs. I had to make a decision; save myself or save this pregnancy," she writes. "This was the toughest decision I've ever made ... [But] today I am relieved. I have to believe that this baby was not meant to be. How else could I explain my rejection of it?" After her third abortion, "Ruth" remembers her boyfriend's visit to the hotel room she had rented for her recovery: "He cuddled next to me and said, 'Don't worry, honey -- our baby's in heaven now.' EXCUSE ME?! We broke up a week later." But, she goes on, "I am forever grateful that I had the choice of abortion available to me, or else there would be three more damaged human beings in the world."

I'mNotSorry.net appears to be a reflection of the classic feminist credo "abortion on demand, without apology." But Beninato's hope, as far as personal activism goes, is that "as more women share their stories, whether with INS or other venues, the stigma attached to abortion lessens just the tiniest bit."

"There's this mainstream, [media-derived] 'script' about the after-effects of abortion," says Penny Lane, 26, a Troy, N.Y., graduate student and creator of "The Abortion Diaries," a three-pronged (documentary video, Web site and film festival) exploration of the subject. "I guess I expected my abortion to change my life completely," she says. "Even though you've only seen, like, three movies about it in your whole life, you've developed this idea of what abortion is like."

Influenced by the "script," Lane was unprepared for the emotions that arose after her own abortion three years ago. "I felt guilty for not feeling guilty," she recalls. "I expected I would suffer a lot. Because I didn't, I felt like a monster."

Lane looked "literally all over the Internet" for advice to help her handle those emotions, but found mainly pro-life literature disguised as unbiased pregnancy resources and pro-choice Web sites that didn't offer much beyond statistics. Frustrated, she began to plan "The Abortion Diaries."

"Most of the abortions in America are about convenience," Lane says. In "The Abortion Diaries," she will "explore what convenience means" by speaking with women of various backgrounds who chose to terminate their pregnancies, usually under circumstances where they were simply too young or unprepared for children. Lane is correct about the convenience factor. According to a study by the Alan Guttmacher Institute, only 1 percent of abortions are a result of rape or incest, and just 6 percent combined are due to health problems in the fetus or the mother. "People need to accept abortion for what it is: a valid part of the reproductive spectrum," Lane declares. "I want it to be seen as normal; if 1.3 million women in this country have one every year, it's gotta be normal."

Gwen Goldsmith, a 42-year-old actress and seminary student from Brooklyn, was recently interviewed by Lane for "The Abortion Diaries." "[Motherhood] was something I wanted to do later," she says, about her choice to have an abortion when she was 21. "I wanted to be Judy Garland, to sing, act, dance. I wanted to travel and see the world." Thus, her decision to abort wasn't especially tough. "I didn't think of a fetus as a baby. [I thought] my responsibility as a human was to live the best life I could, and leave the planet a better place. That was not going to happen as a mother at 21." Goldsmith says she "never had a moment of regret."

But that was then. Reflecting on the decision today, Goldsmith admits that the choice she made 22 years ago is more complicated since she found spirituality. "I believe that an abortion is a murder of a fetus -- different ethically than the murder of a child, but still a death," she tells Lane. "But I swatted a fly earlier; I'm a murderer. I'm also a carnivore. It's a choice."

During the course of the interview, Lane tells Goldsmith about her own abortion. "I remember feeling conflicted about the magic of being pregnant," Lane says. "I felt electricity running through my body. Not for a minute did I not think of it as a life. I knew it was a baby."

Though Goldsmith doesn't regret her abortion, she grows teary-eyed as she concedes that being 42 and single will probably prevent her from having a child. "I'm proud that I didn't fall prey to society's opinion that because I'm a woman, I have to have a baby," she says. "My sadness is that I couldn't have the best of both worlds."

As Goldsmith illustrates, these decisions -- even when made without regret -- can be complicated and contradictory. Feelings can change, or muddle with time. But Goldsmith is OK with that. "I've learned I have the right to say yes or no, and change my mind at any time, without apologizing," she explains.

Even Lane's feelings changed as she recorded these women's stories. "I knew it would be interesting and important, but I didn't figure out why until I started doing the interviews," she says. "As I listened to the stories, I found my own assumptions and prejudices falling away -- about what a woman who had had multiple abortions would be like, or [one who says] that she never wants to have kids."

Joh (Joanna) Briley is one such woman. After getting pregnant at age 17 by her first love, Briley, a 35-year-old MTA worker and stand-up comic from Brooklyn, N.Y., didn't think twice about having an abortion even though her boyfriend -- and his mother -- begged her otherwise. "In high school you shouldn't be pushing a stroller," she tells Lane, on camera. "So I took care of it."

After watching a TV news segment about Baumgardner's "I Had an Abortion" shirts, Briley, who had another abortion four years ago, ordered three. "They're almost like slang, desensitizing a word," she notes. Though the shirts are too small for her to wear -- Briley often bemoans the 30 pounds of ex-smoker's weight she recently gained -- she displays them on clothes hangers in her apartment. The irony isn't lost on her. "I was like, that's kind of an art statement!" she laughs.

Recently, Briley began writing stand-up material about her abortion. Her audience's reactions to the jokes were predictably mixed -- for the most part, women laughed and men didn't get it. "I want to buy more T-shirts to pass out to my audiences," she says. "I want to let [women in the audience] know it's OK if they've had abortions. It's not like, 'Oh, I went to pick up some shoes, and then I got an abortion.' But a woman shouldn't feel she can't talk about it."

While Briley's incorporation of her abortion into her stand-up routine is an example of the individualized activism that Baumgardner and others are trying to encourage, she doesn't view herself as an activist -- or even a feminist. She just sees herself as an "everyday woman" who made a decision that was, for her, the best one. "I don't want children, and that's my choice. To know that somebody wants to take away that right -- wow. How can you tell me what to do with my body?"

She goes on. "I shouldn't have to defend my decision. If it's selfish, fine. I'm living how I want to live. People can question me, but I don't care. I had an abortion. I should start saying that every day."

If Briley does start talking about her abortion every day, Baumgardner will feel like she's accomplished her goal. "People want to tell their stories; they don't want to sit there moldering in shame. [This movement] is about cracking open and changing the tenor of the debate a little bit."

Shares