In 1984, my father was ordained a Roman Catholic priest. Not a priest of some breakaway sect, but a real collar-wearing, Communion-distributing, last-rites-offering, rosary-in-his-pocket priest. He was part of a small group of married former Episcopal priests who converted to Catholicism and received exceptional permission from the Vatican to continue their sacramental duties without renouncing their conjugal vows.

I was only 10 years old at the time, and I accepted his decision without much ado, save for a brief declaration that I would stay in the Episcopal Church so I could keep singing in the choir. When my parents acquiesced and told me they would ferry me there every Sunday, I realized my stand was not rocking the foundations of my family in quite the way I had anticipated. I immediately recanted and converted too.

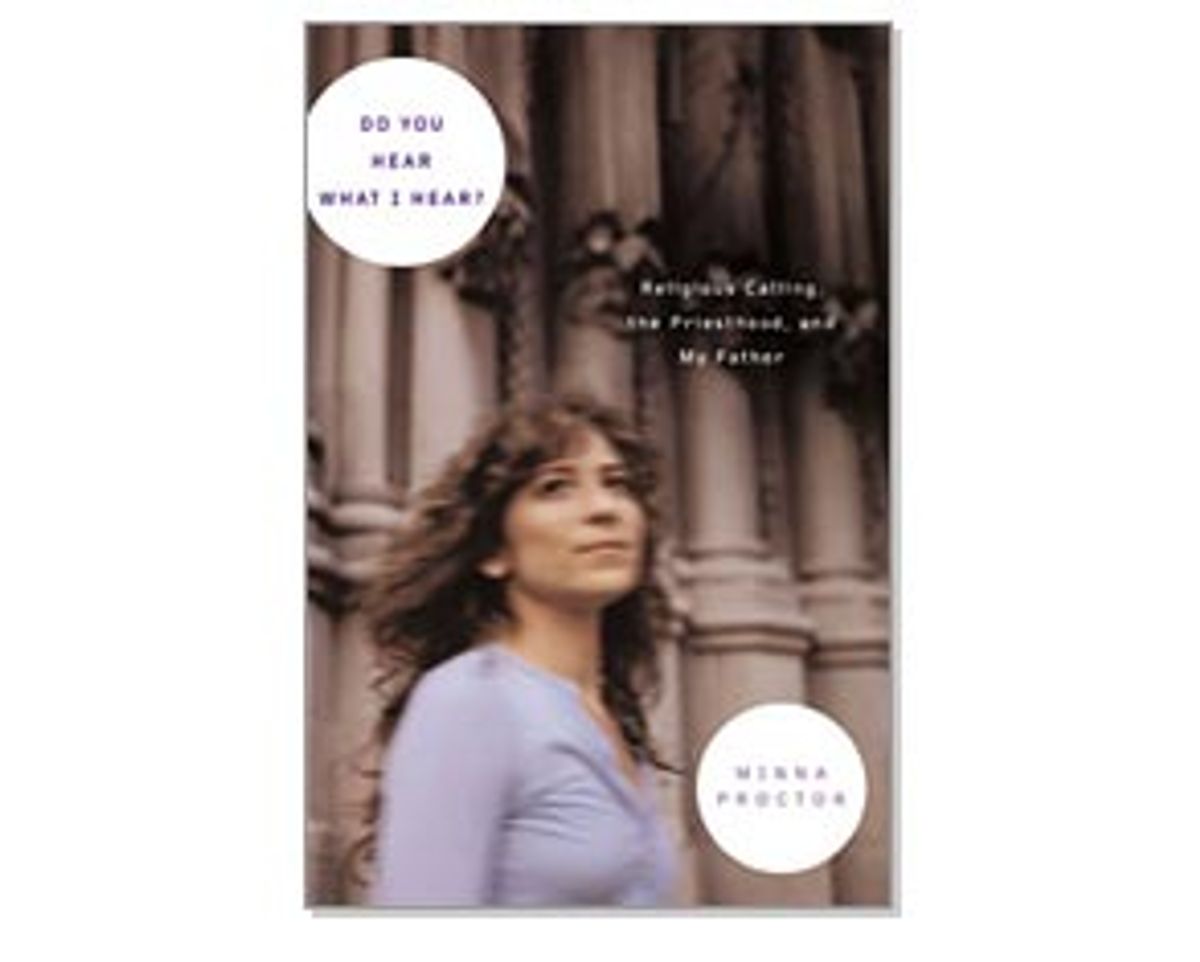

Five years ago, Minna Proctor's father made a similar announcement -- he told her he wanted to become an Episcopal priest. Considering the fact that Proctor had been Bat Mitzvahed -- she was brought up in various university towns by her lapsed Catholic father and secular Jewish mother, both academics -- the news came as quite a surprise.

Since her parents' divorce in 1979, her father had joined the Episcopal Church, but Proctor took little note. He was remarried, with two children by his second wife, and was living in Ohio, while Proctor divided her time between New York and Italy. Rather than just check in with him periodically to see how the ordination process was going, or rebel, as I tried to do, Proctor, currently the editor of Colors magazine, turned to her skills as a writer to "attack apparently unconnectable dots."

How one becomes a priest is certainly a process unknown to most, and in "Do You Hear What I Hear? Religious Calling, the Priesthood, and My Father," Proctor's just-published memoir and thoughtful study, she sets out to trace the path in detail from the perspective of a "virtuous pagan." She discovers an intricate, often grueling journey encompassing serious self-reflection, meetings with parish committees that probe a candidate's spiritual calling and motives for seeking ordination, examination by committees appointed by the diocese bishop, psychological evaluations to weed out criminals and pedophiles.

When her father is turned away early in the process, placed on a sort of priestly wait list and advised to reapply once he has better clarified his reasons for wanting to become a priest, she expands her focus and explores the idea of religious calling in general. Her own journey leads to texts by St. Ignatius, Thomas Merton and William James and interviews with priests, bishops, nuns and monks.

At a cramped Brooklyn patisserie not far from her apartment, Proctor spoke with Salon about the impact of her father's decision on their relationship, the need for secular people to inform themselves about religion, and the difference between spiritual calling and the more worldly, bureaucratic process of becoming a priest.

You don't consider yourself religious. How did you feel when your dad said, "I'm thinking about becoming an Episcopal priest"?

At first, a whole lot of nothing. I sort of digested it for a period of time and then found myself talking about what a funny thing it was with my friend Alex, who was an editor at [the now defunct online magazine] Feed. He said, "Why don't you write about it?" So I took my steno pad and went to find out how you get to be a priest. It was such a naive mission -- first of all, the idea that it could get figured out and then represented in 1,200 words. And then, in the course of my first interviews with my father, it was emotionally stunning. If I had known a lot more about the church and about religion I would have known that spiritual stories tend to be thorny stories. I was expecting something sweeter, smaller and filled with goodwill and aspirations. But it was far more twisted than that.

Was it hard for you to delve into your father's personal faith?

Yes. But it was also a privilege and a responsibility. I spent about a month being all fucked up because he was talking about his divorce, about not being a good dad. I think that was the most startling thing to me, too, because I'd spent my life building a narrative so that I wasn't disappointed in my father. You build your parent into someone who you accept, and you don't hold a grudge. This was something I'd done all my life, and to suddenly have that undone by him saying, "Oh, no, I screwed up," I wasn't prepared for that.

In the book you point out that your father says he lost his moral center in the '70s when you were born and growing up. That must have been difficult to hear.

The idea that he didn't have a moral center made me ask the question, what is a moral center? What didn't he have? What didn't he give me? What would he have liked to teach me that he didn't, and did I get it by myself? Some of that came to larger metaphysical questions about being a religion-less child. I thought of people I know who had grown up with strong religious structures. And at least they knew what they did or didn't have. If they were lapsed, they knew what they were throwing aside, or if they weren't lapsed they knew what they were clinging to.

There was a whole world that your father had that you never shared with him. Suddenly he's saying, "I am religious. I'm very religious." That had to come as a bit of a shock.

It was a total shock. And as I explain in the book it wasn't like he hid it over time. It was just that I didn't pay attention. I knew he was going to church and I thought, "How nice. He has a community, he does this, it's something he enjoys." But I never even thought of him as being religious. I guess I didn't feel comfortable using that label. In my world being religious meant being a fanatic, and I knew he wasn't.

Was it scary writing a book about religion -- a topic that you really knew nothing about?

The biggest challenge was waking up in the morning and opening Kierkegaard and thinking, "Who the hell am I to think that I have anything to say about this, or that I can even understand what anybody's talking about?" On the other hand, I had to keep reminding myself that all I could do was be me, a secular person, exploring this topic. In a way that's one of the narrative conflicts of my book, that I'm not a religious scholar, but that I do believe that religion is not a subject that only religious people can engage in debate about. Religion has a growing role in political debate right now, and I think it's better if all of us were more informed and didn't think of religious people as fanatics. If you do that, then it becomes a debate about fanaticism instead of a debate about much more interesting and important ideas -- moral ideas, a sense of social responsibility. Even secular people can talk about and have opinions about religious topics, and we should.

You meet a lot of interesting people in the book. What surprised you along the way? Were there moments when you thought, "I can't believe someone's saying this?"

I was amazed when the bishop of Indianapolis said, "Of course the church messes up. We have to mess up or else we would have to believe the Inquisition was a good thing." I had thought that the church, any church, was an absolutist organization, and it's not. Religion is constantly evolving, and I think that's a cool thing about it. Not all of them, and the ones that's aren't are either favored for that or in trouble for that, but there's a tremendous diversity. I was surprised at how open and thoughtful and considerate people were, because I had this idea that they were fanatics, and fanatics don't change their opinions. I don't think anyone said anything that shocked me in a negative way. I don't think anybody said anything hateful.

You struggle with the idea that the notion of calling and the positive journey of self-knowledge the church demands from those seeking ordination may be compromised by this earthly, bureaucratic process of determining who gets to be a priest. At one point you worry it might be like a witch trial or a form of McCarthyism. Did you ever reconcile this?

I think there are cases in which one compromises the other. The notion of calling and the way that the Episcopal Church works on it is actually fantastic. They really require candidates to reflect on why they want to become priests, and what their role is in society. I want to draw a distinction between that and an entirely different process, which is how priests are named. The church as an organization has an entirely legitimate, indeed important, responsibility to choose their priests, to choose them carefully and with attention. But I think they're different questions. People should have their spiritual journey, figure out their calling, and that should be one thing, and the church should figure out who they want or don't want as a priest, and that should be another thing. What I didn't like was when the two kind of overlapped and the bureaucratic process almost took the Lord's name in vain.

How so?

When the bureaucratic process says, "You're too old to become a priest, so God didn't call you." One's a fact, and the other is what God wants. There's a lot of disagreement even within the Church about to what extent we can say what God wants. Don't say [to an applicant who has been rejected for the priesthood], "It's because God doesn't want it." Say, "It's because the church doesn't want you." My confusion in the book was, did they say no to my father because he wasn't called, or did they say no because they didn't hear his calling or because they weren't listening? I think this kind of discernment process is important for figuring out what you're called to do, whether it's the priesthood or something completely different. Instead of helping my father find his calling they just sent him away with his confusion. The thing is, the word "calling" is used ambiguously. Sometimes it's a divine call; sometimes it's an institutional call. Their rejection didn't specify which.

There's a point in the book where your sister complains, "Wait a second, dad already has his first family that he doesn't devote enough time to, and here he is taking on this larger family, the congregation, or wants to, and where does he get off doing that?" That speaks to the feelings of children of clergy members or any sort of religious officials where they must feel some resentment at times.

That's a very astute point. Are you the child of a clergy member?

Yes, I am. Once, when I was interviewing a pastor, her daughter called. She was supposed to be at some church community service project, but she hadn't shown up, and I could just feel trouble brewing in this family. I sensed she was acting out against the commitment her mom had made to her congregation, possibly to what seemed to the daughter a neglect of her family at home, and against the notion of the minister's perfect family.

I think it would apply to the feelings of any child of a parent who is committed to a huge job in a way where they are making choices between family and work --an E.R. surgeon, a soldier, a missionary, an activist. What makes it particularly more intense for children of clergy is the language -- the semantics of family and father. If Father Chuck is not a good dad to his kids, then where does he get off being a father to anyone else?

Did your experience writing the book cause you to reflect on your own secular Judaism?

Yes. I was really struggling with, as we talked about earlier, this idea that my father said he didn't have a moral center. And I started to think about mine. I read a lot about secular Judaism. I read [Arthur] Hertzberg's "The Jews in America," which is a fantastic book. My grandfather was a secular Jew, my mother is a secular Jew. But never for a moment an embarrassed Jew. I certainly always thought of myself as Jewish, and in the course of this book and in the course of doing things like going to church and standing in pews and listening to sermons, I really felt a difference between being in a synagogue and being in a church.

How did you feel different?

Recently I heard about a woman who was confused about her Jewish identity because every time she went into a church she felt like dropping to her knees and the angels were singing. The language she used was completely one of conversion, the way people talk when they convert to Christianity. I didn't have anything that you could say, "And then the skies broke open." It was just a comfort level. Right after 9/11, for example, I went to a synagogue, and it felt like home. After a similar, non-public tragedy happened to me, I was in a church, and I felt like I was an anthropologist. Being at church while I was writing the book felt like open-minded, friendly reporting. But when I was in a synagogue it felt like home.

You write that as a product of an interfaith marriage, you often felt neither here nor there, or part of both. That's confusing for a kid, especially when neither of your parents was particularly religious when you were growing up.

I think it's more confusing when there's no religion. The other day someone called something "treyf," which means non-kosher. I was at my mother's house and I didn't know what it meant, and she turned around and looked at me and said, "I really didn't teach you anything, did I?"

Shares