Celine Joiris has never failed a test. Never eaten crappy cafeteria food. Never been picked last during gym. It's not that she's a supernaturally lucky 16-year-old -- she's simply never been to school. "I like the idea of studying, but school is just like incarceration," she explains. Her brother Julian, 17, agrees. "My approach is, planning, schedules -- OK. Tests, OK. College, OK. Whatever. But I don't really want to think much about it," he shrugs. "I can't tell you where I'll be in two years."

What's that? A smart 17-year-old without a plan? A bright, middle-class teenager who's not stressing out about SATs and admissions essays? In an era when college prep begins in preschool and adolescents need Palm Pilots to manage their after-school activities, such nonchalance has the power to shock. What about all those stories about home-schooled kids dominating national spelling bees and hogging spots at Harvard? Surely "whatever" is not in their vocabulary.

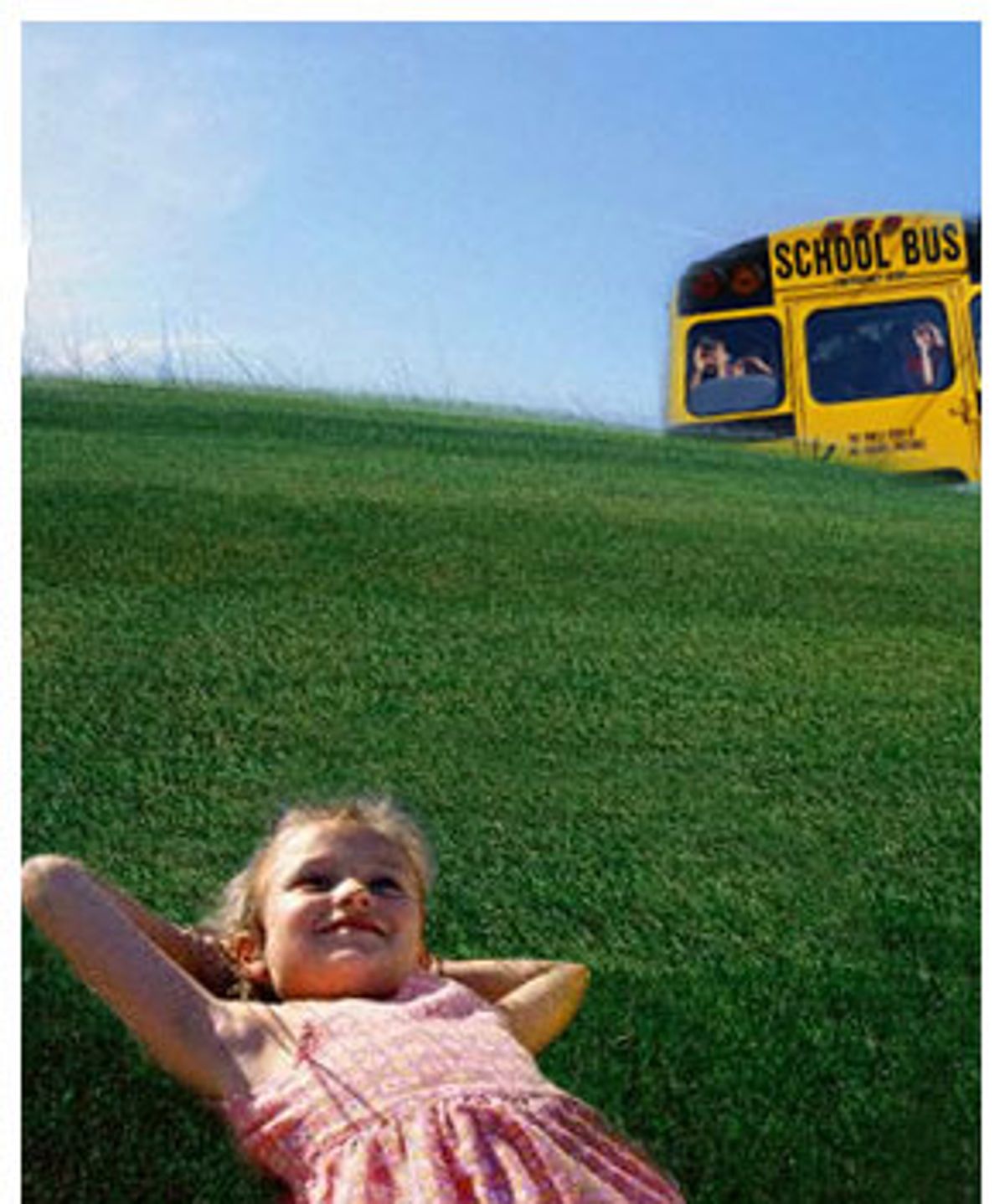

But Celine and Julian Joiris are not your typical home-schoolers -- they are unschoolers, followers of a radical approach to education that rejects not just the routines of traditional school, but the authoritative ideology it represents. Unschoolers make up approximately 5 to 10 percent of all home-schoolers. They learn without teachers, curricula or exams; rather, their whole lives are laboratories in which skills and smarts are acquired piecemeal, through casual interaction with the world around them.

In the last decade, the number of Americans who home-school has surged at a rate of 29 percent a year, to include more than 1.1 million adherents nationwide, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. But as their ranks have swelled and the movement has become more accepted, some of the contrarian ideals that once made it revolutionary have been diluted. Though there remain some real religious and ideological differences between traditional students and home-schoolers, on a practical level, at least, life for many home-schoolers bears a similarity to that of their public school counterparts. They work in online classes and with prepackaged curricula. They have tutors and field trips. They compete with one another over who has the most impressive internship and collect offers of admission from elite universities.

"When you buy a curriculum and set your kids down five days a week, except in the summer, all you're doing is playing school at home," says Sandra Dodd, a mother of three unschooled children from Albuquerque, N.M., and an outspoken unschooling advocate. "Most home-schoolers, especially Christian home-schoolers, believe that schools are too liberal and too lax," she explains. "On the other hand, unschoolers believe that schools are too inflexible. Our objections to school are 180 degrees apart from their objections. And so we are not only not on the same team, but school is actually closer to what they're doing than we are."

Since 1960, when A.S. Neill published "Summerhill," a chronicle of life at his "free-learning" British boarding school, and American educational reformer John Holt coined the phrase "un-schooling" in his books of the late 1970s, the philosophy has emerged as the rebellious twin of the home-schooling movement. While paired in many people's minds, the two have distinct agendas and ideologies. "It is a distinction that is as old as the home-school movement itself, and is an artifact of the fact the movement grew out of both the alternative school movement of the 1970s and the Christian day school movement," explains Mitchell Stevens, professor of humanities and social sciences at New York University, and author of a definitive study of contemporary home-schooling. "And those distinctions reflect a larger tension in American culture in differences as to how we should raise our kids."

Indeed, while it is largely unschoolers' laissez-faire approach to learning that shocks the uninitiated, the most radical aspect of unschooling may not be the manner in which it approaches education, but the way it challenges parents to reimagine childhood. In "How Children Learn," published in 1967, John Holt wrote: "All I am saying is ... trust children. Nothing could be more simple -- or more difficult. Difficult, because to trust children we must trust ourselves -- and most of us were taught as children that we could not be trusted." Thirty years later, the belief that children are essentially capable creatures -- curious, independent and resilient -- is still at the heart of unschooling.

But since Holt wrote those words, American parenting has undergone a tectonic shift. "Good" parenting now seems to be a skill rather than an instinct, something learned not from trial and error, but from self-help authors, life coaches, psychologists, consultants and parenting experts. Whether it is "The Baby Whisperer" pledging to "solve all [parents'] problems," or Dr. Phil McGraw promising a "step-by-step plan for creating a phenomenal family," the prevailing sense is that the world is a demanding, dangerous place, tamed only by discipline and determined planning.

For parents fed up with the micromanagement of their children's lives, unschooling appeals because it disregards conventional wisdom about giftedness, age-appropriate learning, and competition. "There is a sense that the kind of intensive parenting we see increasingly among upper-middle-class families is something that is driving a large portion of people crazy ... and unschooling can be read as a kind of dissent toward that hyper organization," says Stevens. "So while in some ways it can be just as intensive as other approaches, at least it's on your own terms, and on your turf, and you're not beholden to the half-dozen organized activities you've enlisted your child in."

Despite the revolutionary tenor of their ideas, unschoolers claim they aren't zealots. Advocates insist that unschooling produces creative, unconventional kids, but even they acknowledge that such a life is not for everyone. Combing the Web, on message boards like the one at www.unschooling.com, it is not rare to see a message from a mother who writes, "My son is 10 years old and has been doing the unschooling method. His reading is advanced [but he's] struggling in math. I'm starting to worry he's learning nothing."

Laurie Chancey, now 25, was entirely unschooled until college -- and remembers how frightening the early years felt for her and her mother, Valerie Fitzenreiter. Living in rural Louisiana, they were true renegades, cut off from a larger unschooling network that exists on the coasts and under relentless criticism from family and neighbors. When Laurie was 6, a relative turned her in to the truancy board, prompting a series of threatening phone calls and angry letters. But Valerie, who went on to write an influential book about their experience, "The Unprocessed Child," remained unwavering. "Mom had been so bored in school and after reading 'Summerhill,' she decided she would unschool me before I was even born. It was amazing, but she just had this complete faith that I would learn what I needed to learn when I needed to learn it, in the face of everyone's opposition," says Laurie. "Finally, when I started to reach my mid-teens, other people could see that I wasn't an idiot and I'd be OK."

"I admit, when we started this 20 years ago, we were just a bunch of radicals on the Lower East Side -- writers, artists and musicians -- who thought that we knew our children better than the public schools," says Francoise Joiris, Celine and Julian's mother. But over time, she says, her motivations have taken on deeply personal meaning. "My father was a professor and often took me out of school to travel with him," she explains. Once, when they were living in Virginia, he volunteered to teach her classmates history at their home when the local teachers went on strike. "That experience was amazing," remembers Francoise. "And by the end, not one kid wanted to go back to school."

As a mother, she has tried to approach her own children's education with the same joy and freedom. "When we were little, we did a lot of workshops with friends," recalls Julian. "One friend's mother was a doctor and she would have a group of us over a few times a week to talk about science. The next year, she gave a Shakespeare workshop, and we read plays, acted them out, and made our own costumes." As small children, they often tagged along with their mother while she worked as a dog trainer for films and television. (Now Celine is herself an accomplished dog trainer and frequently competes in canine agility trials with Francoise and their two Norfolk terriers, Stamp and Fleet.)

Their days at home were loose and unstructured, filled with hours reading on the living room futon or playing homemade quiz games about Greek mythology and geography, calling off nations from a map. While occasionally Francoise nudged them in a certain direction, by suggesting a book or an activity they might enjoy, in the end she felt it was important that Celine and Julian call the shots. Since entering adolescence, both have been entirely in charge of their own schedules, attending tai chi classes twice a week and volunteering part-time as antiwar activists. Julian, a devoted member of the New York Assembly of the Society for Young Magicians, performs regularly around the city for other home-schooling groups. Still, both admit that some weeks pass in a blur, without anything to show for the hours. "There are times that I'll spend a bunch of days hanging around the house, bored," says Celine. "Then I start to feel guilty."

Indeed, despite her idealism, Francoise doesn't pretend her family has found utopia. Though they have been at it for 16 years, even Celine and Julian's father, Chris, a painter-turned-architect who didn't want to be interviewed, has had a hard time embracing the unpredictability of his children's future. "He supports it," says Francoise, "but I don't think there's one of us that hasn't at some point worried, what if my child still isn't reading at age 15?" In the end it often comes down to the strength of parents' convictions. "The real problem most people have," says Francoise, her face serious, "is that doing this requires too much faith in kids, too much work on the parents' part -- and no guarantees."

For all its iconoclasm, and to the chagrin of some critics, unschooling is entirely legal. Every state has a set of standards that govern home-schooling, and which unschoolers must also obey -- though their interpretations of those guidelines are sometimes rather loose. But because levels of oversight differ enormously from state to state, it happens to be far easier to unschool in Oregon than in Pennsylvania. In New Mexico, Sandra Dodd has been able to unschool her three children from birth through their teen years, with little interference from the state. When her daughter Laurie was 11, Valerie Fitzenreiter discovered she could register with the Louisiana Board of Education as a "private school" and never reported in again.

In contrast, in New York, where the Joirises live, families submit an IHIP (individualized home instruction plan) each summer outlining the material they expect to cover in the coming months. New Yorkers also face periodic standards tests: every other year before the 4th grade, and annually after that. But for the Joiris family, at least, unschooling's unorthodox methods seem not to have been an academic handicap."The exams were never as scary as I expected," remembers Julian. "In seventh grade, he refused to study any math, and I was terrified he wouldn't pass," says Francoise. "But after Julian took the test, he said, 'It was fine. I only got one wrong.' And he was right; he did."

After talking to a dozen unschooling families and studying their blogs and message boards, I've found countless similar tales of sucess. But outside that small circle, even among liberal home-schoolers, unschooling still provokes uneasiness. Gail Paquette, a home-schooling mother of two and the founder of the Web site Hometaught.com, is one of unschooling's most vocal critics. "A child-led approach may develop the child's strengths but does nothing to develop his weaknesses and broaden his horizons," she writes. "I [mostly] disagree with the premise that children can teach themselves what they want to learn, when (and if) they want to learn it. Certainly children do learn some things on their own, but their often roundabout way of going at learning is not necessarily the best way."

Indeed, given the temptations and distractions of everyday life, is it unreasonable to wonder how much kids can really learn when just left up to their own devices? Conventional wisdom tells us that when not compelled to study the basics of reading and writing and arithmetic, the average kid will fritter away the day playing video games and flipping TV stations. And while unschoolers argue that that is an unfairly pessimistic take on children's curiosity and innate abilities, it would be hard for them to deny that their approach can lead to the acquisition of idiosyncratic skills. When she went off to her freshman year in college, Laurie Chancey was already a gifted computer programmer -- but struggled to get through a class in remedial math.

She is hardly alone. Dependent as it is on the changeable passions of a child, unschooling is replete with 10-year-olds who can explain the subtle differences between the Mesozoic and Paleozoic eras but can't complete a multiplication table. In a make-or-break world where kids are measured by advanced-placement credits and varsity letters, if an interest can't be showcased on a résumé, is it a waste of time?

"Kids in traditional school spend a whole lot of time learning penmanship, and things like that don't really matter in the long run," counters Chancey, who is on her way to earning a Ph.D. in sociology from Louisiana State University. "I know it scares a lot of people to think of divorcing from the school system entirely, and lord knows, people have all sorts of odd reactions when I tell them about my background. But luckily, in my case, I'm succeeding in a very traditional way, so it's easy for me to say, 'Look at me, I did OK. This can't be all bad.'"

So while unschoolers aren't groomed their whole lives for Ivy League admissions, that doesn't mean they won't end up there anyway. Celine Joiris has been working as a volunteer at New York's War Resisters League and hopes to live and work in Paris for a few years before applying to Harvard. Julian has no immediate plans for college, but continues to study the concert violin and has steadily been attracting gigs as a magician. Somehow, without a battery of grades and tests to prove it, these kids know they are smart. Without their parents providing a map, they feel ready for the future. "As we get older, I think things are going to get less complicated," says Celine, with just a flicker of a smile. "I mean, at some point, people stop asking what grade you're in."

Shares