Ever since she was in her early teens, Mary Worthington has been vehemently opposed to contraception, which she regards as immoral and dangerous. To spread her anti-birth-control gospel, this month she launched No Room for Contraception, a clearinghouse for arguments and personal testimonials on this subject. NRFC joins other anti-contraception Web sites like Quiverfull and One More Soul.

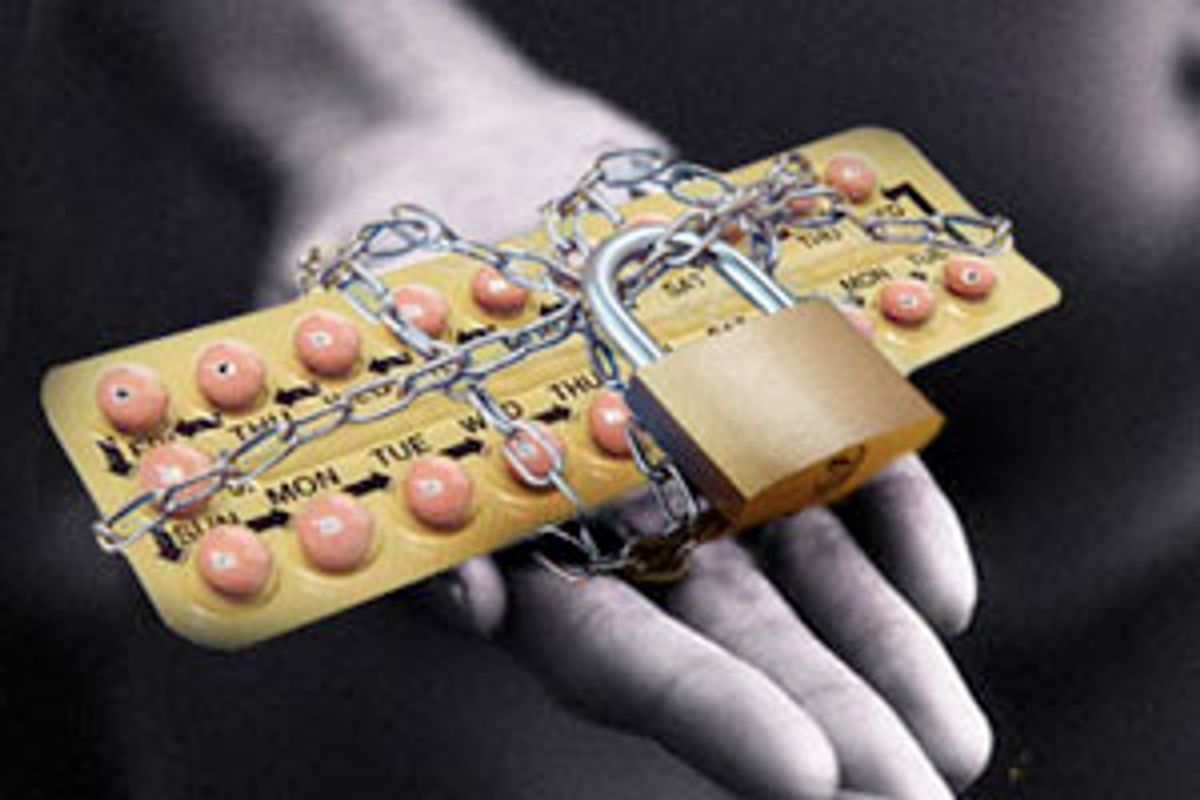

Worthington, who wouldn't reveal where she lives and works, or her exact age, is a recent graduate of Franciscan University of Steubenville, in Ohio, where she earned a B.A. in theology and a minor in human life studies. She is also opposed to abortion. But NRFC doesn't even address abortion; its sole purpose is to "prove" that the pill and the IUD cause health problems and destroy women's fertility, that condoms lead to the spread of sexually transmitted diseases by making people believe that sex can be completely safe, that contraception destroys marriages by rendering sex an act of pleasure rather than one of procreation. Emboldened by the fact that the president and the two most recent Supreme Court nominees are anti-choice, a recent antiabortion victory in South Dakota, and legislative success restricting access to emergency contraception, groups like NRFC are shifting their focus and resources away from abortion and putting their energy into restricting birth control.

On the face of it, their fight seems doomed. The vast majority of Americans support access to birth control: According to a National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Association poll last year, even 80 percent of anti-choice Americans support women's access to contraception. And with the exception of a dwindling number of devout Catholics, a large majority of American women have used or regularly use some form of contraception. Perhaps most telling of all, no mainstream antiabortion organization has yet come out against contraception, a sign that they know it would be a political disaster.

Still, the anti-birth-control movement's efforts are making a significant political impact: Supporters have pressured insurance companies to refuse coverage of contraception, lobbied for "conscience clause" laws to protect pharmacists from having to dispense birth control, and are redefining the very meaning of pregnancy to classify certain contraceptive methods as abortion. In increasing numbers, women and men opposed to contraception are marshaling health facts and figures to bolster their convictions that sex for anything but procreation is morally wrong and potentially deadly. Although its medical arguments are really just thinly veiled moral and religious arguments, using findings that are biased and unfounded, the rising anti-contraception movement, echoed by the Catholic Church, is making significant inroads. Leaders of the pro-choice movement know it, are worried about it, and realize they can't take it lightly, as they mount their own strategies to battle it.

"It is very hard to awaken people to the threat," says Gloria Feldt, the former president of Planned Parenthood, "because who can believe that something so accessible can be at risk? But that's what [people] said when they started attacking Roe, and now look at how close we are to losing Roe."

Nor is the fight against birth control only the province of a few zealots. While sites like Worthington's may be new, many antiabortion activists have always been bitterly opposed to contraception. "After Roe v. Wade was decided," says Feldt, "the debate focused on abortion instead of birth control. But [for anti-choicers] they are not separate issues." She points out that what we're seeing today is more of a revival of an old movement than a shift to something new. "It's been there from the beginning. If you go back and look at the rhetoric against birth control from 1916, it's exactly the same as the rhetoric now."

And when you look closely, there is evidence to suggest that even the mainstream anti-choice groups are ready to make the battle against contraception part of their agendas. Many of the National Right to Life Committee state affiliates have opposed legislation that would provide insurance coverage for contraception. Iowa Right to Life even lists a host of birth control methods -- including the pill, the IUD, Norplant and Depo-Provera -- as abortifacients. And NRLC itself parses its language very carefully when it comes to contraception. A call to the organization resulted in an e-mailed statement on the group's position that read in part, "NRLC takes no position on the prevention of the uniting of sperm and egg. Once fertilization, i.e., the uniting of sperm and egg, has occurred, a new life has begun and NRLC is opposed to the destruction of that new human life." Such a position leaves the group plenty of wiggle room to argue, when it is ready to do so, that contraceptives prevent the implantation of a fertilized egg and are thus a form of abortion. (NRLC wouldn't comment further, because, according to a media relations assistant, contraception lies outside of its purview. For the same reason, Feminists for Life refused interview requests. And at Concerned Women for America, a group that has been openly anti-contraception, a spokesperson told Salon twice that none of its experts were available for interviews.)

"The brilliance of the other side is that it's such a wholesale attack, that it's hard to find an entry point," says Cristina Page, vice president of the Institute for Reproductive Health Access at NARAL Pro-Choice New York, and the author of "How the Pro-Choice Movement Saved America: Freedom, Politics, and the War on Sex." While pro-choicers are busy trying to save Roe v. Wade, the anti-choice movement is "laying down their game plan for this next wave." And, she adds, "On every single front, whether it be educational, whether it's a matter of direct access, or whether it's about funding, their campaign is on, and it's effective."

For those who are pro-choice, the idea of fighting to ban both abortion and contraception seems contradictory: Contraception, after all, lessens the number of abortions. But once one understands what the true social and moral agenda of activists like Worthington is, and their attitude toward sexuality, the contradictions vanish. For them, sex should always be about procreation; since contraception prevents conception, it is immoral. At a deeper level, they believe that women's biological destiny is to be mothers.

Feldt says, "When you peel back the layers of the anti-choice motivation, it always comes back to two things: What is the nature and purpose of human sexuality? And second, what is the role of women in the world?" Sex and the role of women are inextricably linked, because "if you can separate sex from procreation, you have given women the ability to participate in society on an equal basis with men."

The anti-birth-control movement has seized recent headlines about emergency contraception -- and the fact that many people are unfamiliar with how it works -- to put forth its view that E.C. is tantamount to abortion. Page sees the anti-choice movement using the "same exact arguments that they make for abortion for contraception," which includes "reclassifying contraception to be abortion. As abortion becomes more constricted," Page says, "these campaigns will begin to intensify, as we're already seeing with E.C."

Indeed, the anti-choice push to keep emergency contraception (such as Plan B) from being available over the counter, and to protect pharmacists who refuse to fill prescriptions for it, has centered on the argument that E.C. is an abortifacient. "Confusion is one of their strategies," Page says, pointing out that anti-choice activists don't bother to distinguish between RU-486, the "abortion pill," which terminates an early pregnancy, and emergency contraception, which is simply a higher dose of the standard birth control pill and helps prevent pregnancy. "How many people hold the misunderstanding that E.C. is a method of abortion shows how effective this movement is," she says. Indeed, in a 2003 survey of women in California, only one in four knew the difference between RU-486 and E.C.

"The emergency contraception debate has been in the news a lot lately," notes Worthington, and "it got me thinking of the need for more resources like [NRFC]." Worthington, who also maintains an anti-contraception blog called the Revolution, says that she hopes to educate young people on the detrimental effects of contraception, and also give older women who have used birth control a forum to talk about how it harmed their marriages. (A section on the site, "Testimonies," so far offers two personal stories, reprinted from the Priests for Life Web site. In both, the writers tell of the grief they felt when they discovered the "truth" about how the birth-control pills they were taking caused abortions.)

Worthington and other anti-choice activists simply don't distinguish between E.C. and abortion. "Contraception is an abortifacient," she says. "Look at the package insert for Plan B. It says it can act to alter the endometrial lining and prevent implantation. It's not technically an abortion, because pregnancy has been redefined to mean 'after implantation,' but it's still taking the life of a human." But there is no proof that Plan B prevents a fertilized egg from implanting in the uterus; in fact, it's scientifically unknowable, because it's scientifically unknowable if an egg is even fertilized until it implants in the uterus. The American Medical Association defines pregnancy as the moment when implantation occurs; even if Plan B did prevent implantation, it still wouldn't be ending a medically defined pregnancy.

"The anti-choice movement," says Feldt, "completely ignoring scientific fact, is attempting to redefine pregnancy as the moment of conception, the moment when sperm and egg meet. At the root of that is the attempt to get the fertilized egg more status than a woman."

And as Page points out, once a fertilized egg is considered a human life, it's just a hop from there to concluding that the standard birth-control pill is an abortifacient, too. "Basically, it's the same pharmacology," she says, "so if you're against emergency contraception and you're lending validity to the argument that it's abortion, you're saying exactly the same thing about the birth-control pill. If somebody out there thinks Plan B is abortion, they think the birth-control pill is abortion." And there's proof that this argument is working: Some pharmacists and even physicians are not just denying patients E.C., they're also refusing to dispense the pill.

Page also notes that the anti-choice movement has succeeded in pushing legislation that, though seemingly unrelated to contraception, helps support its cause. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, at least 15 states have fetal homicide laws that apply to "'any state of gestation,' 'conception,' 'fertilization' or post-fertilization" -- meaning that one can be convicted of manslaughter or murder for destroying a fertilized egg, even if it hasn't implanted itself in a woman's uterus.

Another successful campaign has centered on condoms. In 2000, at the behest of then-Rep. and anti-choice ally Tom Coburn, R-Okla., the National Institutes of Health convened a panel of experts to evaluate the condom's effectiveness at preventing the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. The panel concluded that correct condom use definitively protected against the spread of HIV and gonorrhea, and that there was "a strong probability of condom effectiveness" for other STDs, including human papillomavirus (HPV). Coburn used the findings to declare that condoms don't protect against HPV -- a wild misappropriation of fact that has nonetheless become a big part of the anti-choice argument against the condom's efficacy. Under pressure from Coburn and other anti-choice activists, the Centers for Disease Control was forced to revise its Web site fact sheet on condoms. There is now a box in the center of the page that reads, in part, "While the effect of condoms in preventing human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is unknown, condom use has been associated with a lower rate of cervical cancer, an HPV-associated disease" -- not quite the same as saying, as the CDC previously did, that condoms protect against HPV.

Such subtle shifts in language have helped anti-choice activists to argue that condoms actually help spread STDs such as HPV by giving users a false sense of security. "When condoms are distributed to youth, they are more likely to engage in the activity," says Worthington. And that's why, she says, they're at risk for everything from AIDS to unintended pregnancy. "In the real world, everyone knows that condom use is never 100 percent correct," she says matter-of-factly.

While no one is suggesting that activists like Worthington will ever succeed in outlawing condoms or the pill, they are making incremental progress in passing laws that are making access to birth control more difficult. Of the 23 states that mandate employers to provide insured coverage for prescription contraceptives to their employees, 14 have exemptions for religious employers, and Missouri allows any employer, religious or secular, to deny coverage for any kind of contraception. During the 2005 legislative session, more that 80 bills in 36 states were introduced that would restrict minors' access to birth control. On the federal level, the Health Insurance Marketplace Modernization and Affordability Act, currently being considered in Congress, would allow insurers to ignore state laws mandating contraceptive coverage. And then there is the matter of pharmacists and "conscience clause" laws. South Dakota, Arkansas, Georgia and Mississippi already allow pharmacists to refuse to fill contraceptive prescriptions. And at least 15 states have legislation pending that would allow not just pharmacists to refuse to dispense prescriptions, but would also protect cashiers who refused to ring them up.

"There are more laws on the books and proposals to welcome pharmacists to obstruct women's access to birth control than there are pharmacists willing to do it," says Page. "99.9 percent of pharmacists know their role is to fill prescriptions and not to make moral judgments."

That doesn't mean that a law on the books wouldn't have a practical effect. "Once you have it as a law," says Chip Berlet of Political Research Associates, a progressive think tank that tracks campaigns meant to curb human rights, "you organize more and more pharmacists to refuse dispensing pills."

One reason for the new push to restrict birth control may have to do with changes in the Catholic Church -- although this is hard to prove, because like many anti-contraception campaigners, Worthington insists that her site has nothing to do with Catholicism, even though she identifies herself as a Catholic and NRFC is filled with discussions of Catholic texts, like the "Humanae Vitae" and the Bible-study document "The Truth and Meaning of Human Sexuality." Still, Berlet sees a connection to the appointment of Cardinal Ratzinger as pope -- an appointment that radically conservative groups like Human Life International have enthusiastically supported. "I think they see in the Vatican some room to push this issue further to the right," says Berlet.

Like the Catholic Church, NRFC opposes the use of contraception even within marriage. The "About Us" page on the site claims that "the constant promotion of and use of contraception leads to promiscuity, and a general lowering of morality and furthers the idea the sex has nothing to do with childbearing or commitment. When this attitude is brought into marriage, it can taint the relationship from the beginning."

NRFC sees the availability of contraception as the root cause of the need for abortion. The "About Us" page also quotes a passage from the U.S. Supreme Court decision on Planned Parenthood v. Casey to argue that "In law and in practice, [contraception] led to the necessity of abortion because contraception proved not to be failsafe": "[F]or two decades of economic and social developments, people have organized intimate relationships and made choices that define their views of themselves and their places in society, in reliance on the availability of abortion in the event that contraception should fail."

In order to support the idea that contraception is dangerous, Worthington publishes articles on the site that take qualified language from scientific studies and distort their conclusions. One of them, "Oral Contraceptives declared carcinogenic by World Health Organization," takes the news that the WHO found that estrogen-progestogen-based contraceptives increased a woman's risk for breast, cervix and liver cancer while decreasing the risk for endometrial and ovarian cancers, and concludes: "It does not seem logical that any woman would place her body at risk for these deadly cancers, even if for the sake of reducing the risk of other cancers. Meanwhile, in the process a woman on The Pill is destroying her fertility. Medical doctors and researchers agree that one of the best ways to prevent some common cancers (such as breast cancer) in women is to conceive and bear a child and to breastfeed naturally. This is the body's natural means of protecting itself from cancer."

Worthington doesn't mention that the WHO concluded, "Because use of combined estrogen-progestogen contraceptives increases some cancer risks and decreases risk of some other forms of cancer, it is possible that the overall net public health outcome may be beneficial." Nor does she qualify her assertions with the fact that the WHO reviewed only previously published data, much of it gathered under studies conducted at a time when birth-control pills contained much higher levels of hormones than they do now. And her citation on breast-feeding comes from the anti-abortion group the Coalition on Abortion/Breast Cancer.

Finding these inconsistencies requires digging below the surface of the site -- on the face of it, Worthington presents her cases persuasively, and couches her arguments in the rhetoric of women's empowerment rather than that of morality. In another piece, titled "Chemical contraceptives kill her sex drive," she takes as her starting point a January 2006 study in the Journal of Sexual Medicine about the relationship between the birth-control pill and sexual desire. Worthington notes that "the conclusion of the study states that while there is a link between chemical contraceptives and a decreased sex drive, more evidence is needed for an accurate correlation to be seen." But then she blithely continues: "If The Pill is causing such trauma and stress in the lives of women, why is it promoted as the be-all, end-all for worry-free sexual relations?"

Worthington goes on to conclude: "Because of the use of hormonal contraceptives, men are equipped with the means to abuse women."

When asked to clarify that statement, she replied, "Chemical contraceptives are promoted as a means by which a couple can have sex all the time with no worries, but how can you expect a woman to have sex if the man is making her take a pill that decreases her sex drive?"

Chip Berlet calls this kind of explanation "faux feminist rhetoric": "It ... changes the appearance of what side you're on." Indeed, if you ignore their ultimate conclusion that birth control should be eradicated altogether, many of Worthington's arguments look a lot like feminist arguments. Concerns about the correlation between sex drive and the pill have been raised by pro-choicers, too, and on Worthington's blog is a startling post railing about how unfair it is that a male birth-control pill will probably never exist because men don't want to risk impotence, and women are expected to handle their side effects in stride. Take out the phrase "morally offensive" in relation to contraception in general, and there's not much in the argument for a pro-choice feminist to disagree with.

Frances Kissling, president of Catholics for a Free Choice, points out that there is a conscious effort to appeal to that "segment of the women's health movement who are suspicious of chemicals and IUDs and want to lead a natural life. There is that part of the [anti-choice] movement, and people who make Web sites like these see themselves as in alliance with women concerned with those issues." Kissling says that this too is part of the Catholic movement against contraception. "This anti-birth-control stuff is part of two things: One, a conservative Catholic, mostly lay, movement to try to cast sexuality in attractive, natural terms," meaning that "sex is beautiful, sacred, wonderful in the context of your body as a temple, only in marriage, and contraception is unnatural, chemical, dangerous." Secondly, it's an "attempt to promote natural family planning."

Natural family planning is, in a nutshell, a more advanced, scientifically updated version of the rhythm method. Worthington says that NRFC doesn't explicitly promote natural family planning, although it's a "practical application" of her message against contraceptives. NFP is mentioned frequently on her site, and she is careful to correct any suggestion that NFP is a type of contraceptive practice: "Contraception destroys fertility while NFP works with fertility," she says. It is "a scientific understanding of a woman's body -- recognizing when would be a good time to abstain, and when would be a good time to have a child"; she adds that it "requires self control and maturity."

Kissling agrees that "the science has advanced as to knowing when ovulation occurs, which makes it reasonably reliable." Just as we know when a couple trying to conceive should have sex, we know when one trying not to should abstain. "The problem," she says, "is with 'periodic abstinence,' abstaining during ovulation with safety window on either side -- the problem is abstaining from sex." Realistically, very few couples are going to be able to follow a strict schedule of abstinence for very long, even if they sincerely want to try.

Still, says Kissling, because it doesn't require hormones, and because proponents claim that NFP means that men have to be more in tune with a woman's ovulation cycle, "there is a belief among Catholics that they could seduce feminists into using natural family planning."

Yet, all evidence points to the overwhelming unpopularity of NFP. "The incidence of Catholic use of this method is no more than 5 percent [according to the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth]," says Kissling. "Catholics don't want to use it, don't accept this theology of the body. Very few people are buying what's on these Web sites, but they have the same kind of appeal to young people as chastity pledges, or the Silver Ring Thing." Basically, she says, it's about the church finding "new ways to sell an unpopular contraceptive method."

Further, NFP relies on the assumption that there is a period in a woman's cycle when she's not at risk for becoming pregnant, an assumption that may be false. Cristina Page points to a study that shows 40 percent of women may develop pre-ovulatory follicles as many as two to three times during one cycle, and thus it may be impossible to know exactly when they are ovulating. This helps explain why NFP has a whopping 25 percent failure rate.

Despite the unpopularity of NFP, the insistence on it and the taboo against birth control among some very strict Catholics -- and evangelicals, an increasing number of whom oppose birth control at least outside of marriage -- don't seem to be preventing abortions. In a paper titled "From Patterns in the Socioeconomic Characteristics of Women Obtaining Abortions in 2000-2001," researchers Rachel K. Jones, Jacqueline E. Darroch and Stanley K. Henshaw found that 40 percent of women in that year who had abortions identified themselves as either Catholic or evangelical.

"We know that birth control is 85 percent effective in reducing abortion," says Cristina Page. "If it's not [100 percent] effective even while legal, we're moving onto a campaign that will exponentially increase the need for abortion."

For those on the pro-choice side of the question, restricted access to birth control doesn't just mean an increase in the number of abortions; it means the loss of other benefits as well. Contraception has given women the freedom to put off marriage, to go to college in greater numbers, to bring more wanted children into the world, and to find good jobs and thus bring more wealth into their families. Asked how he responded to the charge that banning contraception would turn back the clock on these advances, Ruben Obregon, Worthington's co-founder in NRFC, responded: "Do you think a woman who has had an abortion feels that killing her unwanted child is an advance? My friends who have had abortions don't exactly feel this way." Obregon added, "It's interesting how you fail to mention the high divorce rate, children of broken families, the spread of HIV and other STDs, all of which could arguably be linked [to] the impact of contraception on society."

Obregon, who would only respond to questions via e-mail, and who refused to divulge his age, religion, location or line of work "out of respect for my family and my next of kin," and because "it just opens things to ad hominem attacks," also added, "And then there is the potential problem of not having enough gainfully employed workers to support those on social security." Asked to clarify whether he meant that Americans needed to procreate more to create more workers, he replied, "No, you are saying that. Nice attempt to put words into my mouth."

Any attempt to clarify Worthington or Obregon's position, or to get them to back up their claims, led to more misdirection, fuzzy arguments, or, at best, questionable and clearly biased studies. To the suggestion that the problem with condom failure rates had to do with a lack of sex education, that distributing condoms without education was like throwing someone a deflated life jacket and not teaching them how to inflate it, Worthington responded, "What we're talking about here is the difference between something that is morally wrong and something that is morally indifferent. What is morally wrong is having sex before marriage."

Ultimately, Worthington and Obregon's fight isn't about birth control or abortion then, but about changing the way people live. Worthington admitted that she thought "sexuality is a gift from god," and that she believes in "abstinence until marriage"; asked why she didn't state that explicitly on the site, she hesitated before replying that it was "something we didn't feel was important to mention, because what we felt was important to point out was the dangers of contraceptive use."

According to Page, there's no way to distinguish the anti-choice and religious arguments anymore. "The anti-choice movement has become a religious movement, and because of that, their interest isn't in reducing abortion. In fact, reducing abortion has become problematic for them, because they want to strip Americans of using birth control, in effect to change the entire family structure."

Page says she has noticed, too, that some anti-choice groups tend not only to oppose birth control, they also oppose child care. In her book she points to some troubling statistics and anecdotes: Ninety percent of senators who opposed the 1993 Family and Medical Leave Act are anti-choice; in the 2004 Children's Defense Fund ranking of the legislators best and worst for children, the 113 worst senators and Congress members are all anti-choice; Web sites like Lifesite and that of the Illinois Right to Life Committee post reports linking child care and aggression; Focus on the Family, the Family Research Council and Concerned Women for America stress the damage that day care can have on a child. (Most of their information comes from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development's Early Child Care Report, which has been debunked again and again and again.) "The trifecta is ban contraception, ban abortion, make child care impossible," says Page.

Frances Kissling agrees that the ultimate message is that "mommy should stay home and take care of the kiddies. This is bound up in this notion of men at the head of a family, of women's identity as linked to their biological capacity, that men and women are complementary and different, that a woman's primary function is motherhood."

The site's inconsistencies and seemingly pro-feminist viewpoint support that view. "If this was 1885, people reading this site would see it as very internally consistent," says Chip Berlet. "It's implicitly patriarchical, but it's the Victorian patriarchical position -- it's not just pre-Vatican II, it's pre- the last century: Put women on a pedestal; protect them from the dangers of the outside world."

So why does it still resonate with some people? "For a lot of people it hasn't been real good here in the post-Enlightenment -- people have lost a connection to family and community, and they're confused," says Berlet. "The mythical reconstruction of the past where men were men and women were protected by the men is a cozy idea."

But if the post-Enlightenment comes with its collateral damage, there's collateral damage to pushing the ideals of traditional marriage as well. Martha Kempner, director for public information at the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS), points out that "for many young people, this completely ignores the reality they're living in now. There's no [room for an] alternative family structure. Say if your grandparents are raising you: You're not as good, your family is not as good."

Kempner thinks that, in the face of the anti-birth-control movement and Web sites like NRFC, the pro-choice side has to have "as many, if not more, places where [people] can get real information. And we have to teach critical thinking skills -- one of the most important things a comprehensive sexuality education can do is teach you how to look at information and understand what makes it scientific, what makes it biased, and what makes it opinion."

Kempner also thinks that, often, pro-choicers may be too quick to dismiss the importance of seemingly absurd claims. She points to a quote from Wendy Wright, president of Concerned Women for America, criticizing a study that correlated the increased availability of birth control with the decrease in abortion rate: "An 'unintended pregnancy' could be a wonderful surprise, not planned but welcome. Why should the government be in the business of 'preventing' a surprising but welcome pregnancy?" "Sometimes we look at statements like that and see them as completely ridiculous," says Kempner, "and possibly wrongly assume that other people will see how ridiculous they are."

Gloria Feldt says that the pro-choice movement needs to go even further. "Merely responding to attacks or even fighting back won't do; in fact, it will make things even worse," she wrote in an e-mail. Indeed, Feldt believes that even with its sly rhetoric and legislative victories, the anti-choice movement may finally have crossed the line, and given pro-choicers something to rally around. The pro-choice movement, she says, "must come roaring forward with a strong message, stirring policy agenda, and bold expansion of direct services. Motherhood in freedom is an ideal that is steeped in our highest values as a society. We own that ground, and if we claim it, it will not erode."

Shares