I didn't want to see Keith in his casket. I promised myself I wouldn't, but then Pastor Peoples told the 500 mourners overflowing Liberty Hill Missionary Baptist Church in Berkeley, Calif., to form a line for the viewing. And my son Jesse walked ahead of me and took my left hand, and my wife, Katrine, walked behind me and took my right, and so I joined the slow, grieving shuffle around the church, and took my turn at the ornate white and gold coffin, and looked inside.

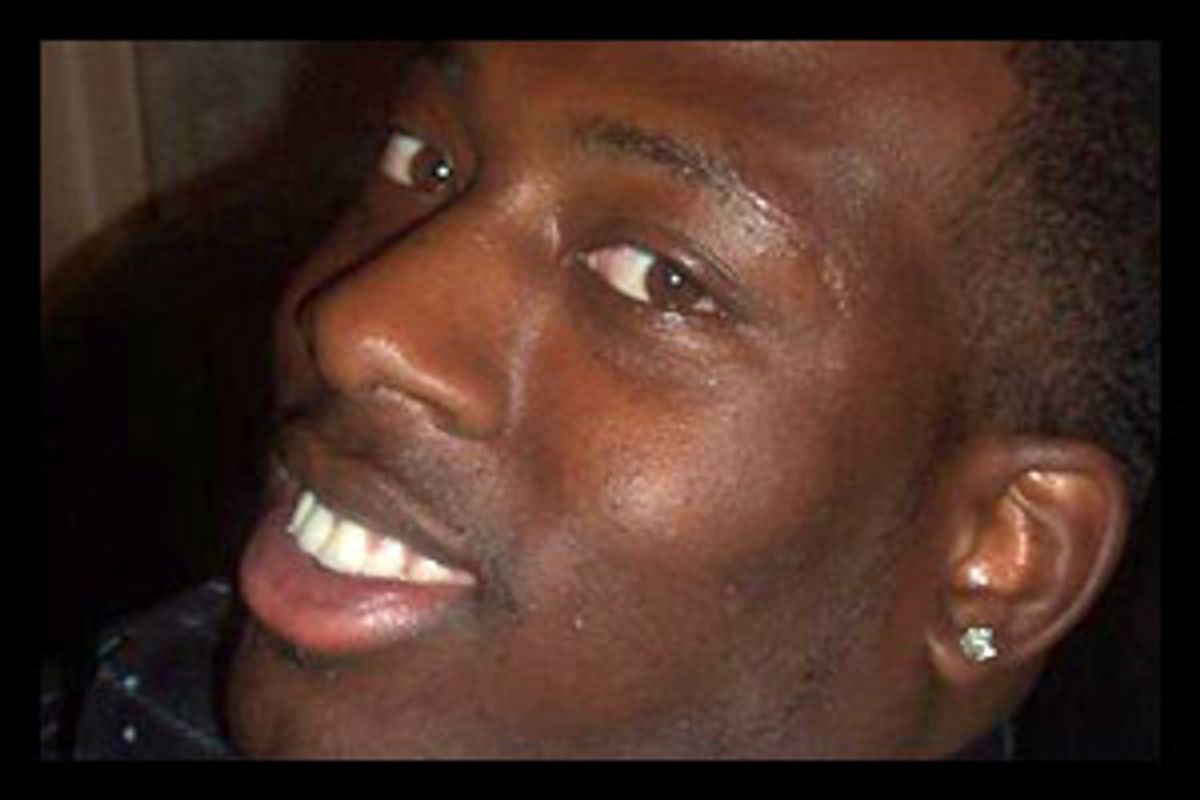

It wasn't Keith Stephens I saw in there. Not that waxy-faced, motionless, solemnly sleeping man. The Keith I loved was an eternal kid at 24, with glossy ebony skin that earned him his nickname "Black" and a flash of white teeth his oldest sister called "his Colgate smile." The Keith I loved could never have lain there so still. He could never have gone that long without laughing, without pulling some prank that made everyone around him crack up. The Keith I loved couldn't be what his father told reporters his son had become: "Just another statistic -- just another young black man getting killed in the Bay Area."

How could it be Keith in that casket? I'd written a book about him and two other Berkeley High School seniors precisely to keep this from happening -- to Keith, to kids like him.

My own sons had gone to Berkeley High, officially the nation's most diverse public high school, but in reality, a citadel of academic and social segregation. I wrote "Class Dismissed" during the 1999-2000 school year to explore the impact of that disparity on the lives of three kids: Jordan, an affluent white boy; Autumn, a biracial super-achiever; and Keith, a learning-disabled African-American football star. Each kid represented a stereotype. As I got to know them, each kid broke through it.

None so much as Keith. On paper he fit the profile. His teachers told me that Keith was enrolled in remedial classes, with grades barely good enough to qualify him for the football team. He came to school late and left early. He was occasionally in trouble with the law. But the bright, handsome kid who showed up for our first interview wasn't the sullen "product of a broken home" his bio had led me to expect. Keith met me at the door of the ramshackle West Berkeley house where his mom had grown up and his grandmother still lived, across the street from a corner liquor store where little boys stood with bikes propped between their legs and bags of Doritos in their hands, and teenage boys slouched against the graffiti-tagged wall. Inside, Keith's grandmother, mother, two older sisters and older brother sat on weary floral couches, surrounded by dozens of framed and thumbtacked photographs of Keith and several generations of his relatives, waiting to interview me.

Once they heard that I was Jesse's mom -- Jesse and Keith were a year apart; they'd played basketball together, and Keith's mom remembered Jesse as "a good eater" -- I was OK with Keith's family. Keith's mom told Keith that he'd have to be OK with me, too. "Keith needs to graduate," Patricia told me. "And you and I are going to make sure he does." Patricia didn't see me as a prying journalist, nor as the objective reporter I was supposed to be. She saw me as a stand-in mom with permission to do what she wished she could: follow her youngest son everywhere, and make sure he didn't sabotage his future.

Objective journalism be damned, I did what I was asked to do. When Keith lingered at Taco Bell too long, I nudged him back to campus before the fifth period bell. When I found him flirting in the halls, I walked by him pointedly on my way to his class -- until he started racing to class ahead of me, insisting that his teachers mark "Casper" (his pet name for me) tardy. In October and again in June, when the cops beat and arrested him, I showed up at the precinct waving my reporter's pad. And when Keith walked the stage at graduation, his eyes glued to his mom's and a Chevy's sombrero on his head, I snapped pictures madly, weeping nonobjective tears of joy. "I would like to thank you for being there for me this year," Keith signed my yearbook. "Iv just none you for a little time but it seems like for ever I have the up most respect for you. Stay cool and after the book don't try to bell out your with me forever. P.s. much love 6-06-00 Keith Stephens."

I didn't bail out on Keith, and Keith didn't bail out on me. He or Patricia, or both of them, called me when he needed a letter of recommendation for the firefighting program at the local junior college or a character witness for a court appearance, or when Keith's relatives were visiting from Texas and Jesse and I were expected at the family barbecue in the park. I took a shift in the hospital when Keith's younger sister, Yolanda, labored with her first son. The whole Stephens clan showed up at our house for my 50th birthday party and, as my white editor and publicist and mostly white friends looked on, Keith draped his arms around my two sons' shoulders, raised a toast, and -- gold grill, diamond earrings, brown eyes and Colgate smile sparkling -- proclaimed himself "Meredith's favorite son."

I cheered when Keith earned a championship ring, playing football at San Francisco City College, and commiserated with Patricia when he dropped out after Gov. Schwarzenegger doubled the fees. Keith told me how boring it was, working nights as a security guard; I praised the latte he made me at the downtown Berkeley Starbucks. Just before his 24th birthday Keith got his favorite job ever, as a laborer on a Richmond construction crew. He was "becoming a man," his mom told me: helping his two single sisters raise their four kids, coaching Pop Warner football, buying junked cars and fixing them up, getting ready to move out of his parents' Richmond house and into his own apartment.

On the morning of Feb. 19 Keith told Patricia he wanted to go to church with the family, something he hadn't done in years. During altar call at Liberty Hill's 11 o'clock service, Keith whispered to his sister, "Tish -- hold my hand." Latisha waved him off, thinking he was joking, as usual. "I'm serious," Keith said. And then he stood up and walked down the center aisle. With the congregation and his astonished family as his witnesses, Keith told Pastor Peoples something that no one who knew him ever thought they'd hear. Offering no explanation, with no known precipitating event, Keith announced that he wanted to give his life to Christ.

After church Keith went off to take care of some business. He'd sold a car to a lifelong friend several months ago, and Dakari (not his real name) still hadn't paid. For the next few hours Keith drove around Berkeley, dropping by places where he thought Dakari might be. A friend of Dakari's told Keith that Dakari had sold Keith's car to someone else. Keith did what he always did when he was upset: He called his mom first, then Latisha. "I'm so tired of people using me," he told them. They gave him the same advice: Go somewhere and chill out. Keith took it. He went to another friend's apartment nearby. Twenty minutes later someone knocked on the door. Keith answered it and was shot once in the chest. By the time the paramedics arrived, he was dead.

Someone called me. I called Patricia and heard her broken voice. "They shot my baby, Meredith," she sobbed. "Just come." Before I left for Richmond I called Jesse, 25 now, and 6-foot-2. Jesse is a grown-up -- an art student, a minister in a predominantly African-American church and a volunteer Bible study teacher at prisons and juvenile halls. But he's still my baby and I cringed at the thought of causing him more pain than he's already known, losing friends to prison and guns. "It's Keith," I told Jesse. I couldn't go on but I didn't have to. Jesse started crying, too.

I drove the 10 miles to Richmond's Iron Triangle, the poorest, most violent neighborhood in the Bay Area's poorest, most violent city. I sat in my car outside the Stephens' baby-blue plywood house. I looked around at the houses and apartment buildings on the block, with their iron security doors and metal-mesh-covered windows, and thought about how hard Patricia had tried to keep her kids -- her tenderhearted, too-trusting youngest son, especially -- off these streets. She'd used her mom's address to send her kids to school in Berkeley, where she and her husband and their parents before them had gone. And now Keith had been killed in Berkeley, a mile from his grandma's house, at the apartment his mom and his sister had sent him to in order to keep him safe.

One of Keith's cousins answered the door. She told me Keith's dad and brother were out somewhere, out of their minds, driving around. I followed the sounds of grief upstairs and found Keith's sisters in their parents' bedroom, each enveloped by several cousins and aunts, each doubled over, making sounds I'd never heard come from a human being before. "They shot my brother," Yolanda moaned. "I want my Keke back," Latisha screamed. "Let it all out," the women holding them murmured. "Go ahead and cry."

Patricia had locked herself in the bathroom. She let me in and fell into my arms. "My baby," she sobbed. "Meredith. They killed my baby." In that instant I understood that Keith had been murdered -- Keith had been murdered -- and my chest cracked open. And the death epidemic among young black men moved from out there, someplace far away, an "issue," to inside me.

Later we all sat in the living room, and I retrieved my phone messages, and told Patricia, Yolanda and Latisha about all the reporters who had called. "You don't need to talk to them," I said. "Don't do anything you don't want to do."

"Bring them on," Patricia said. "I don't want my brother's death to be in vain," said Yolanda. "I want everybody to know what a good kid Keith was," Latisha agreed. Soon a handsome white anchorman from the local Fox affiliate arrived with a cameraman in his wake and a thick hide of orange makeup on his face. He interviewed Keith's mom and sisters, then turned the camera on me. "How does it feel," he asked, "to know that if Keith hadn't been in your book, we wouldn't be covering his death?"

Horrified, I looked to Patricia, expecting to see her face twisted in anger at the question's insensitivity, or crumpled by its sting. But she was nodding. And so were her daughters. "That's not the way it should be," Patricia answered the question for me, "but that's the way it is."

As the cameraman zoomed in on the copy of "Class Dismissed" that has occupied a place of honor on the Stephens' coffee table for the past six years, I realized how many awful truths the people in this family and in this neighborhood know, truths that I had, until then, been spared. What were facts of life for the Stephens and their neighbors -- that people they loved were routinely beaten, arrested, murdered, taken from them -- had been nameless, faceless newspaper headlines, or no headlines at all, for me.

In the 11 days between Keith's death and his funeral, seven people Keith's age or younger -- three of them under 18, all of them African-American or Latino, none of them the subject of a book -- were murdered in Oakland, within a few miles of where Keith died. Their murders made the news, but only because 2,000 outraged citizens showed up at an East Oakland church for a town meeting called by Tavis Smiley, Cornel West, Ron Dellums and Rep. Barbara Lee. "African-Americans actually want to go places in life," a 17-year-old boy told a reporter. "It's a matter of life and death," added a 54-year-old woman. "We're going to perish if we don't stand up."

The day after Keith died, an impromptu altar sprang up in front of his grandmother's house. Reporters milled around asking questions. Keith's football team brought supermarket bouquets and bent down to hug each of Keith's relatives in turn. Eight-year-olds and 80-year-olds wrote messages to Keith on a big white piece of paper taped to his grandmother's sagging red fence. The girl Keith had planned to marry put up the last photos taken of him alive, that Colgate smile the centerpiece of every one.

Keith's grandmother, Mama, put her thin, wiry arms around me, her wig askew, her face gullied by 24 hours of tears. "What are we gonna do, Meredith?" she asked. Mama had asked me that question before. When Keith was arrested and hogtied for playing dice in an alley, we found eyewitnesses who testified on Keith's behalf and got the charges dropped. When Keith was arrested for driving while black right in front of Mama's house, and Mama and Latisha were clubbed and arrested for their attempt to intervene, we held a "Free Keith Stephens" rally in front of Berkeley City Hall. But this time neither of us knew what to do.

"How do you protest this?" I said. "Where do you put the picket line?"

In the days following Keith's death I received 58 condolence e-mails, many from people I don't know: Keith's middle school teacher, the D.A. who prosecuted him, his manager at Starbucks, a Berkeley police lieutenant whose daughter goes to Berkeley High. They wrote about his kindness, his sense of humor, his way with little kids and his smile. They called what happened to him "senseless violence."

But the violence that took Keith's life wasn't senseless. It happened for reasons that any one of us could name -- start with slavery, take it from there. Spending one year in Keith's reality, I learned nothing more predictive than this: Give a kid the message that you'd rather he just disappeared from your store, your classroom, your streets, and sooner or later, one way or another, he will.

"You strip a people of their pride," Jesse told me the morning of Keith's funeral, as we drove to Mama's house to ride with the family to the church. "You strip the men of their masculinity. Then, if someone disrespects a man, to retain his pride he has to kill that person."

In his funeral sermon, Pastor Peoples told the standing-room-only crowd -- many of them African-American teenagers wearing RIP T-shirts bearing other dead black kids' faces and names -- what they could do to change things. "We are descended from kings and queens," he thundered. "We fought for our freedom. And for what? So we can shoot each other?"

The sanctuary exploded with applause.

"We've learned the hard way that violence never solves anything," Pastor Peoples shouted. "But it's hard to teach that to our kids when our government is using violence to try and take over the world."

Pastor Peoples asked the older men to stand and promise the younger men, "I will be your role model. You can stand on my shoulders." He asked the younger men to tell the women, "I will respect you. I will protect you. I will provide for you." He asked the whole congregation to take a vow, "To do what God wants us to do, be who God wants us to be -- in our families, in our community, in this city." Those congregants who weren't sobbing or screaming or falling into the aisles, grieving, shouted out their assent.

It has been five weeks since Keith was murdered. Although his family and friends are sure they know who killed him, the Berkeley police say they have no suspects in the case. The BPD has posted two $15,000 rewards: one for information leading to the arrest and conviction of Keith's killer, the other for the killer of Juan Ramos, an 18-year-old who was stabbed to death 10 days before Keith died, at a high school party in the Berkeley hills, where the rich people live.

Jesse wrote on Keith's altar, "I promise you, I will make this mean something." Since then, Jesse has decided to paint a mural somewhere in the city of Berkeley, to commemorate Keith's life and death.

Patricia called me the other day, hoarse from crying, but with a glimmer of the old fire in her voice. "I need to do something about this, Meredith," she said. "All these kids having guns is crazy. Maybe I should work for gun control." I gave her the number of a gun control activist I know, an affluent white man whose 15-year-old son was accidentally shot to death by his best friend.

Then Patricia asked me what I was going to do. "Same thing I've always done," I said. "Tell people about Keith."

Shares