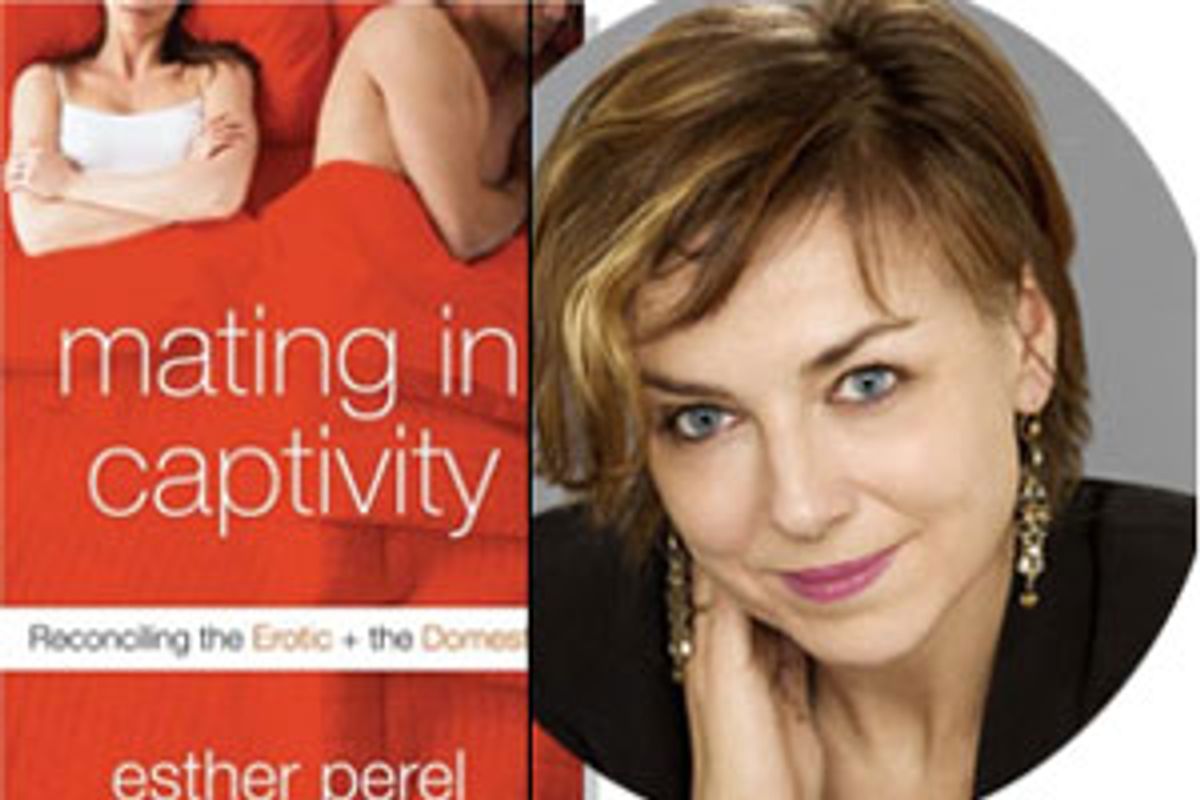

Is it really possible to make marriage feel sexy? Esther Perel, a New York couples and family therapist, argues that it is, but that it involves nothing less than a rethinking of what matrimony has become for most Americans, as well as a hard look at how we deal with the competing roles of parent, worker and lover. In her new book, "Mating in Captivity: Reconciling the Erotic and the Domestic," she takes aim at the modern conception of marriage as a milange of the romantic, the sexual, the economic and the companionate.

Erotic desire, Perel argues, thrives on mystery, unpredictability and politically incorrect power games, not housework battles and childcare woes. Furthermore, increased emotional intimacy between partners often leads to less sexual passion. "The challenge for modern couples," she writes, "lies in reconciling the need for what's safe and predictable with the wish to pursue what's exciting, mysterious, and awe-inspiring."

Traditionally, Perel points out, marriage was a business relationship, designed for procreation and economic survival. It asked nothing more of its partners than stability, reliability and a day-to-day ability to get along. Recent generations added romantic love and sexual passion to the mix, followed by demands for equality after the resurgence of the feminist movement in the late 1960s. As our society placed new requirements on the institution of marriage without stripping away much of its historical functions, we responded by expecting our spouse -- one person -- to provide what in the past it had taken an entire village of people to give us.

Perel, who was born in Belgium and has been married for more than 20 years, views our dilemma with an outsider's perspective. Her advice is refreshingly counterintuitive: Communicate less with our spouses about the minutiae of daily life and speak more with the language of our bodies and our secret desires. Pursue interests outside of work, marriage and the family. Open up about our fantasy lives. Flirt and play with both our spouses and others. And get the kids out of the literal and figurative bedroom even if you have to rent a hotel room to do it.

Salon met with Perel in her New York office, where she discussed the difficulties of combining long-term love with erotic desire, why Americans need to learn to play more in their personal lives, and the modern cult of childhood.

Why do you think so many couples have trouble keeping desire alive in long-term relationships or marriages, even when they are extremely loving?

Relationships are crumbling under the weight of our expectations. We want marriage, companionship, economic support, family life -- and then on top of that we want our partner to be our best friend, confidant and passionate lover. For a long time the idea that passion and marriage could go together was a contradiction in terms. Marriages were about economic criteria. When you chose your mate, or somebody chose your mate for you, sex did not enter into the equation.

Are long-term love and eroticism ever compatible?

I think that they're not inherently incompatible. But why is it so difficult? There is in the experience of love an experience of security, of predictability, of safety, a kind of grounding and anchoring. And eroticism thrives on something very different. It thrives on the unknown and the mysterious, on the unexpected. It's not what you want in a long-term, secure relationship.

Is that true across all societies?

I think that some societies have it more and some have it much less, depending on how much the society experiences seduction and sensuality and flirtation as part of its ecology.

Where does the United States fall on that spectrum?

People don't play much in the United States. Flirting, where you play with the possibilities, goes against the goal-oriented, pragmatic approach Americans often take -- which is, if you go out, you go out to score.

But there's sex all around us -- in music, on TV, in film. Are you saying we're not an erotic culture?

Animals have sex. Sex is an instinct, it's the primordial instinct. But eroticism is sexuality transformed by the human imagination. It is exclusively human. That makes all the difference. It is playful, and in that sense it is inherently unselfconscious and carefree. It has no other goal than the cultivation of sex, of pleasure for its own sake.

Are Americans more comfortable talking about sex than erotic love?

There is a fundamental discomfort about sexuality in our society. That's why on the one hand sex is ubiquitous but we also hang onto these attitudes that are very sex averse. You get both extremes in this country -- abstinence education and talk shows that blabber off every detail of people's lives.

How does the erotic die in long-term relationships?

Often it's not that the erotic energy is gone, it's that it has left the couple. It may be quite present in the house, but it's been transferred onto children or work. I saw a couple recently who had become best friends. In 20 years, they'd had one night apart. They put their passion into making a beautiful home, building the whole thing from scratch. They also put their passions into creating a business together. They have passion. And it's erotic passion, in the sense of aliveness, vibrancy and vitality, but it is not a sexualized passion.

There is a notion people have that in the beginning of relationships passion is spontaneous. They actually forget that the beginning was one big story line. There were hours spent anticipating, planning, plotting, developing the script, imagining what you're going to wear, what you're going to eat, where you're going to go, the whole thing. But people remember things as explosive and in the moment and unplanned. And that's not true. But passion can die because we forgo the willfulness, the intentionality and the imagination that fuel the erotic.

Many of us hope that our marriages will be models of equality between best friends. Yet in your book you say equality and friendship are not necessarily the best ways to preserve erotic love.

I think the equality model is something that we want in everyday life with our partner. But it can have unforeseen negative consequences in the bedroom. Fantasies are rarely egalitarian, I can tell you that. Friendship is a different story. Best friends share everything, talk about everything. And when you're lovers, you want mystery. I've never in my life called my husband my best friend.

Do you think many of us are uncomfortable with fantasy and power plays in the modern conception of long-term relationships and marriage?

The women's movement needed to address the abuses of power. Nobody would ever challenge that. But in the course of doing that, it had some unanticipated consequences, including attempting to neutralize power in places where power is intrinsic. Such as in desire. An element of aggression or hostility is often part of erotic desire. It's not just joy and contentment. There is another side to desire and it's that that we have become uncomfortable with feeling and expressing. The whole point of fantasy is that it's not meant to be reality. We can experience these feelings very comfortably and playfully with a partner, without fearing, What does it say about me?

You say parenthood can have an effect on erotic desire too.

Family life needs constancy, predictability and stability. What eroticism thrives on, family life defends against. And at this point there is an unprecedented child centrality in our culture. We have a kind of a sentimentalization of the child -- well, that's the only value that they have at this point. They don't produce anything and they drain us economically. You put that child centrality combined with a model where the survival of the family depends on the happiness of the couple, and basically you get a 50 percent divorce rate in first marriages. Kids get the latest fashions and adults walk around in college sweats. Kids get languorous hugs and adults must make do with a diet of quick pecks. We need to re-create some boundaries.

Can the erotic nature of the parent-child bond create a lack of passion between a married couple?

There is a powerful, sensual, erotic connection between the mother and an infant or a newborn. There is tickling, kissing, nibbling. Then there is the gaze, that kind of adoring gaze of this little child. It's often very similar to when the couple was first meeting. And it is a sensuality that is more akin to the way that I think female sexuality is organized, that it's less genital, that it's more full bodied, that it's more subjective and contextual. When the mother says to her husband at the end of the day, "I have nothing left to give," I have, on occasion, had to say, "Maybe at the end of the day, there is nothing more that you need." You're satiated. And it is intoxicating, it's like it fills you up completely; it's no surprise that one wouldn't need the scruffy guy after that. But it's not easy to acknowledge that. And it's not what kids need either. They need parents with a healthy sex and emotional life. It gives room for the child to go and do what explorations they need to do and not become the physical and emotional caretakers of their parents.

You don't view a lack of sexual fidelity as a big problem, as many couples -- and many therapists -- believe it to be.

Monogamy is the sacred cow of the romantic ideal. That's why adultery is such a crucial issue. There is a moral edge that many Americans bring to this without sometimes looking at many factors that bring a person to stray. Our model is that marriage is for everything. So, we think if it didn't work out with you, I'm not going to think that maybe there is something to question about my model, I'm just going to say I chose the wrong person and I'll go somewhere else to get everything. And there is something about not wanting to give up on that ideal that makes people more willing to go for divorce, and the dissolution of the entire family system and all the bonds, than the willingness to renegotiate boundaries.

How has your own marriage affected your beliefs?

I say I have had three marriages with the same person. I think we reorganized our relationship completely, at various stages in our life. I married my mentor. Something shifted completely when we had children. I think a third shift took place when our parents died. And what shifted? The balance of interdependence. The power balance, the boundaries between us, the level and kind of negotiation. The balance between togetherness and separateness.

You write that we need to speak with our bodies as well as with language. How do we do that?

I think that our mother tongue is the language of the body. Every mother that has touched a child knows how she spoke with the child and how the child spoke back with his or her body. It is our original mother tongue, long before the first verb is ever spoken. We should certainly not reduce ourselves to just the spoken word. We really need that instrument that we play here, that often is able to express things very differently. I mean, people sit here on the couch and they talk, talk, talk, talk, and then finally somebody puts the hand on the other and it just speaks volumes. That's what they needed, touch. We all need to be touched.

Shares