Medical researchers have decided there really is such a thing as "chemo brain." But I did not need a stamp of authenticity from someone in a white coat to believe in it. I live with it. I know it's real.

Among cancer patients, "chemo brain" refers to both the immediate and the long-term effects of chemotherapy. I started chemotherapy in the fall of 2005. At the end of my first round, I was in a thick fog. Simply scheduling my next appointment was difficult for me. Two older women who were also patients at the cancer clinic kindly offered an explanation for my fumbling mind: "You have chemo fog." Among the more experienced cancer patients, this was a well-known phenomenon.

The chemotherapy I was given for breast cancer was an aggressive, "dose dense" regimen that left my brain scrambled after each session. Even after the worst of each round's side effects passed, I remained in a haze of sorts, with difficulty thinking clearly. Arguably, the shock of being diagnosed with cancer, the disorientation of being suddenly yanked out of a normal, healthy life and thrown into the world of life-threatening disease -- the Big C variety no less -- could be responsible for my mental lapses. But that degree of difficulty had to have an organic source.

Months after my chemotherapy treatments were concluded and the worst of the fog had faded, I was distressed to realize that I was still not functioning at full capacity. First, I became aware of gaps in my memory. People would mention an event or conversation that I had been party to and I would have absolutely no memory of it. I was reminded of the movie "Memento," in which the main character has lost the ability to store anything in short-term memory. When he met someone new he would take a photo of them and write their name on it because he knew that by the next day he would have no recollection of having ever met them.

I have no way of predicting what I will remember and what I will forget. It isn't really the same as ordinary memory lapses -- forgetting one thing from a long list or forgetting something because you were distracted and not really paying attention when it happened. I think I am paying attention, but ... poof! No memory of whatever I was supposed to do, no recollection of a conversation or event. And it is usually so completely erased that I am initially incredulous. "I already told you? Are you sure?"

My medical team -- and believe me, with cancer you get doctors, lots and lots of doctors -- is not particularly concerned about my mental symptoms. Their first concern, of course, was stopping the cancer from killing me. Having successfully removed all evidence of the tumor, they turned their attention to preventing any remaining cancer cells from spreading or forming a new tumor. My prognosis is now very good. My oncologist is not unsympathetic to any of my post-treatment problems, physical or mental, but faced with so many other patients whose prognosis is much worse than mine, I imagine she has difficulty getting too worked up about my forgetfulness.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

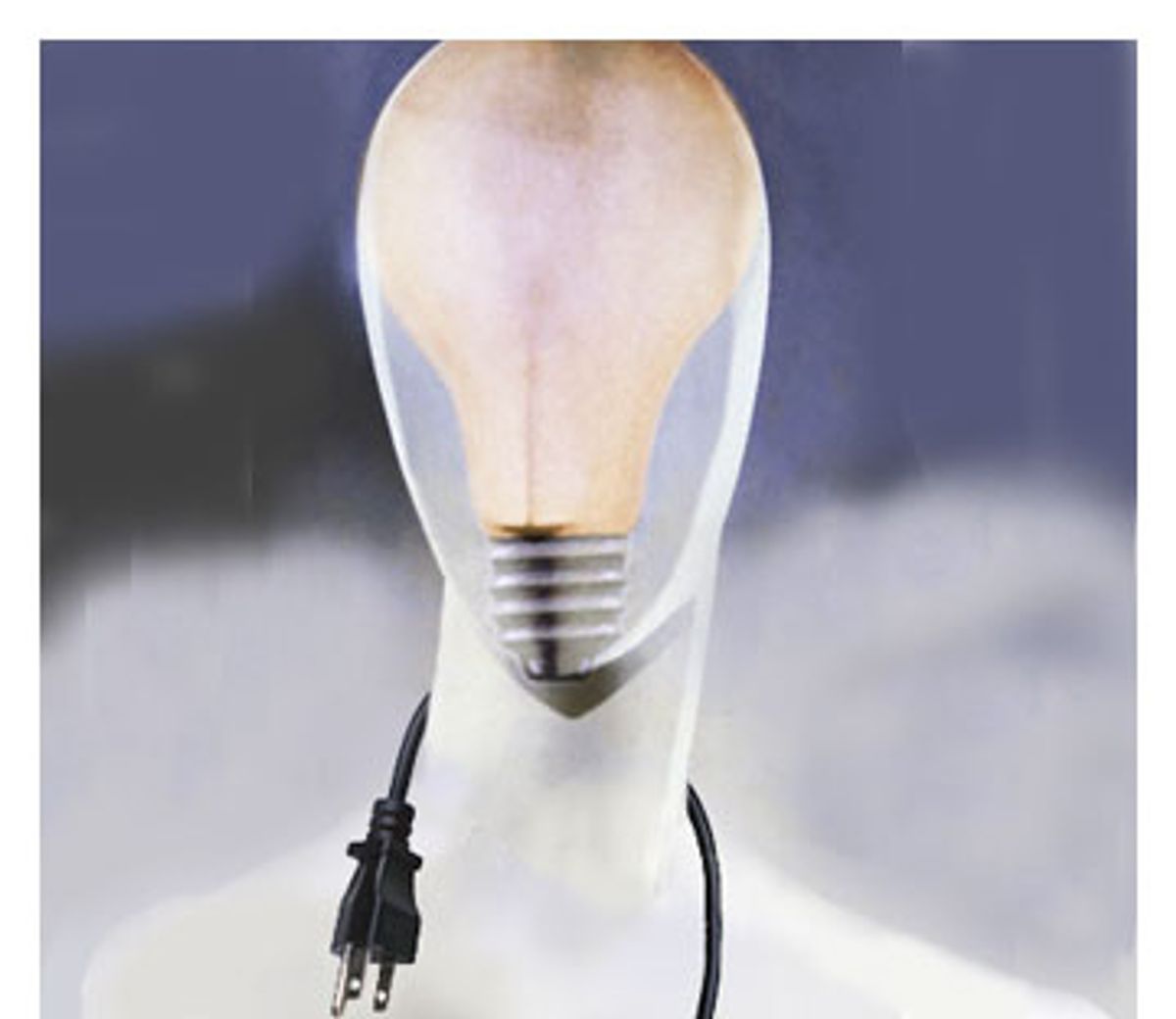

Yet the leaks in my short-term memory continue, and they are only one aspect of the chemo brain that afflicts me more than a year after my last chemotherapy treatment. One of the most frustrating and noticeable problems has been difficulty finding the right word. Of course, this "tip of the tongue" phenomenon afflicts everyone from time to time. But the problem for me is not the occasional inability to recall a word; rather it is the quite frequent inability to name common objects. I look at that thing on the table, but for the life of me I cannot tell you what it is called. "Book." "Envelope." "Cup." Words I taught my son when he was a toddler, he must now supply for me when I am completely incapable of finding them in my chemo-altered brain.

My ability to focus and concentrate is also in disrepair. In my professional life, I research demographic and economic issues and write reports and articles. Not being able to get my thoughts in focus or maintain my concentration has made that very difficult. I have had to find ways to compensate, such as minimizing distractions and doing the most difficult tasks at a time of day when I'm at my sharpest. I sometimes feel as if I just cannot get a mental grip on anything -- as if my thoughts are a swirling jumble of nonsense.

Lately I have noticed some improvement. My need to work has more or less forced me to relearn how to maintain concentration in the face of distractions and interruptions. The inability to recall words also seems to be a less frequent occurrence, perhaps because writing provides me with practice in this area. My memory, on the other hand, is not much improved. Rather, I have learned to ask people to give me a gentle nudge from time to time if I have promised to do something, just in case I have forgotten. I am making the sorts of accommodations I imagine people have to make when they are developing Alzheimer's or have damage to a certain area of the brain.

I hope I will fully return to my old self, but just as I cannot know for sure that the cancer is gone forever, so do I not know how closely I will ultimately be to the person I was before I was diagnosed with cancer.

I try not to complain much about chemo brain. For one thing, I have other, more debilitating problems that overshadow it. Not being able to come up with a word is relatively minor compared to the pain I feel in my feet when I step out of bed each morning, a lingering effect of chemotherapy. The sometimes excruciating joint pain I experience thanks to the tiny tablet I take every day to (hopefully) rid my body of any remaining cancer cells has a far more profound impact on my quality of life than my Swiss-cheese memory. Not being able to shed the more than 30 pounds I put on during my treatments is certainly depressing, and the extreme -- and extremely frequent -- hot flashes that have curtailed many of my activities are perhaps the worst of all. There is also the challenge of coming to terms with losing my breast and learning to live with a reconstructed substitute; I am lucky to have benefited from the skills of a great surgeon, but he could not give me back the nerves that once allowed me to have feeling in that part of my body.

It is also hard to complain when you consider the alternative. Cancer is fatal, after all, and it is these treatments, with all their nasty side effects, that make it possible to survive this nasty disease. But grateful as I am for a prolonged life, I cannot help but wish for my old self back. The physical and mental changes have left me struggling with some of the most basic elements of my identity. I do not look, feel or think quite as I did before. And frankly, I liked the old self quite a bit more than this overweight, achy and forgetful one.

As more of us survive cancer, I would not be surprised if our post-treatment problems spawned a new branch of medicine. There will certainly be a demand for it, because however grateful we are for the treatments that battle cancer, I cannot imagine that many of us will quietly accept being left with a much diminished self, particularly those of us who are members of the boomer generation. If we can overcome cancer, surely we can overcome almost anything else.

Shares