This is a story with a hopeful ending. Lucky, even. But be forewarned, you have to get through a lot of hopeless, unlucky crap before you find it.

Here's how it all starts: My first-born son has autism.

Now that isn't hopeless or, in my opinion, unlucky. Autism isn't sick or crazy. It's rigid and routine, a little eccentric. Autism is multiplying columns of numbers easily while being unable to look anyone in the eyes; listening to only one band's music, and always in the same order, for a period of six weeks; refusing to eat anything orange. It's also being able to remember the exact date and time you ate a bison burger in Chamberlain, S.D., when you were 6. But there's a really charming side to all this, a wonderful tilted perspective on life that, if you're a parent of autism, you come quickly to enjoy.

I was a parent like this.

Until he was 17, my son was unique and funny and odd. He was difficult in some ways but incredibly easy in others. He washed the family's dishes precisely, went to bed at exactly the same time each night, and sorted our mail into careful piles. He did fairly well in school -- above average in math, a little below in social studies -- and spent his weekends playing tournament-level chess. He was a loner, but sweet and articulate and very close to his only brother.

Then junior year came. He met a girl, he went to a dance, he thought life was better. And for a night it was. Then the dance ended, the girl decided she was interested in someone else, and the boy became depressed.

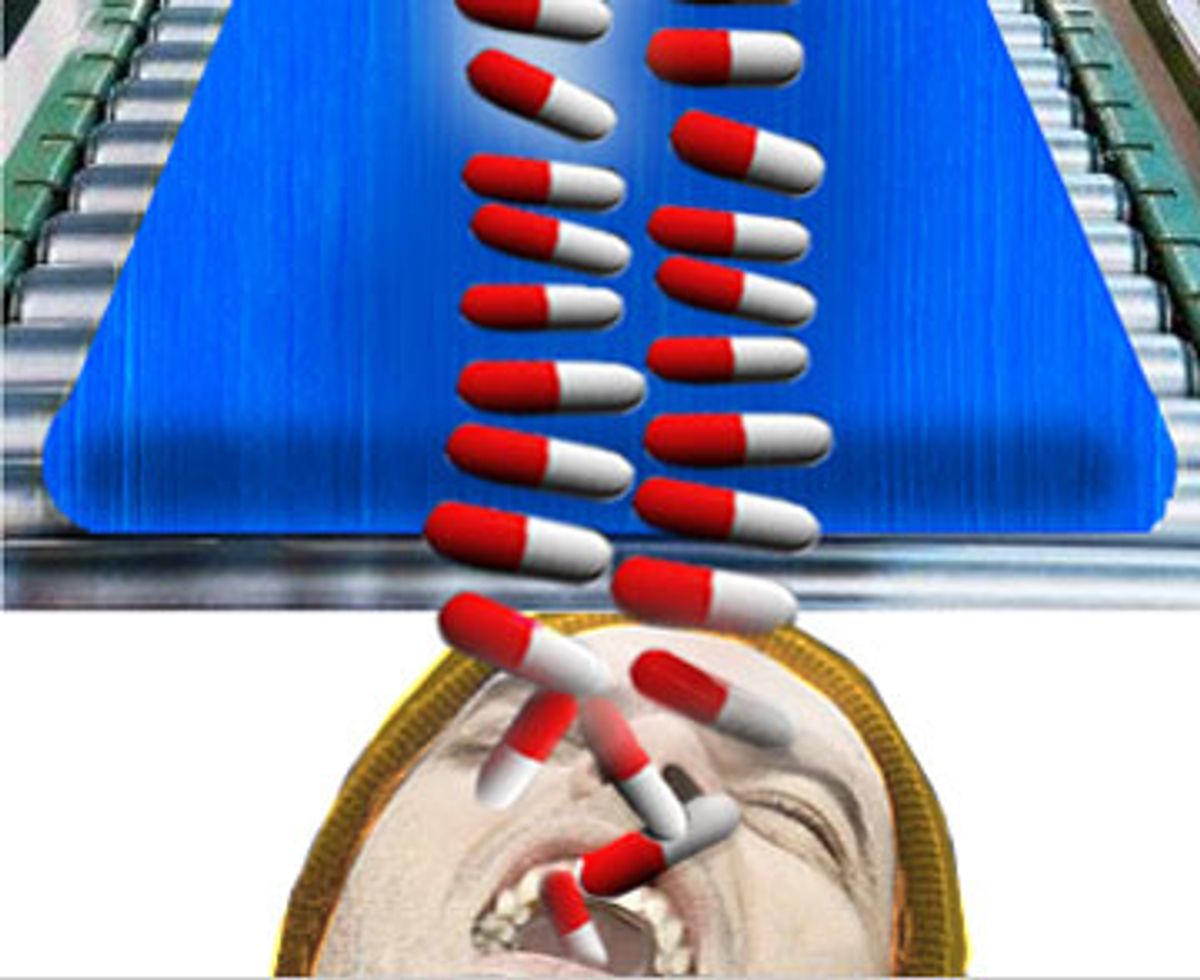

Was this cause for alarm? I thought not. Teenage boys routinely get depressed over girls and fickle friends and school dances. It was painful, but I assumed it would blow over. When it didn't, after six months, I took him to a psychologist who recommended a psychiatrist who put him on a newfangled antidepressant she said would have the added benefit of controlling some of his obsessive tendencies, like stacking the dishes and sorting the mail.

I didn't want to control those things -- to me, these weren't symptoms, they were characteristics of my son. And I'd fought for 17 years to keep him drug-free. But the psychiatrist and the psychologist and several family members insisted: He'd become unhappy, his routines were getting in the way of his developing a social life. This pill, they said, would help him.

Instead, he gained 30 pounds and began to lose his mind.

It happened slowly, over a period of months. First his grades began to fall. There were some random episodes of violence -- nothing major, just an out-of-control moment here or there. A tendency to stand up from the dinner table, after a full meal, and walk to Arby's for a snack. Eerie giggles that seemed involuntary. A flat expression on his once-curious face.

Senior year, he started an after-school job at an auto parts factory but lost it when he couldn't keep up with even the elderly workers. He stopped speaking to his brother entirely and even hit him several times. He lost interest in music, computers and chess.

I talked all this over with his father, my ex-husband, who said, "Maybe he needs a man's attention. Let me give it a try."

So our now 18-year-old, autistic, depressed and quickly losing ground, moved across town, to live with his father in a small, quiet apartment. My ex worked odd shifts, so our son began wandering the city on foot, early in the morning and late into the night. He told his dad about how he had to fight the bad thoughts that were crowding in his head. And when he wasn't out walking, he slept a lot -- around two-thirds of his life, in fact -- despite the fact that he drank 12 to 15 cups of coffee a day.

Together, my ex-husband and I took our son to a highly respected neuropsychology clinic housed in a suburban office building. The doctors there even looked like bankers; they wore regular clothes and carried clipboards and fancy pens embossed with the names of drug companies, rather than stethoscopes.

After meeting our son twice, they conferred with the original psychiatrist (who, we discovered later, was employed by the same large healthcare conglomerate) and came up with an altogether new diagnosis. This wasn't autism at all, they told us, but "psychomotor slowing" -- a form of schizophrenia. Our son was just unlucky, they said sadly, the victim of two devastating neuro-behavioral disorders. Completely unrelated.

It was critical that we begin treating him immediately; they couldn't stress this strongly enough. We were given a prescription for a brand-new antipsychotic medication with the inspiring name Abilify that was direct-to-consumer advertised in Newsweek and Time magazine. It featured a woman gazing into an azure sky and copy promising the drug would work on the brain "like a thermostat to restore balance."

We were skeptical. But the experts were firm: He would continue to deteriorate if we didn't catch this now. Did we want our son to end up institutionalized? In jail? Sick to our stomachs and desperate, we gave him the drugs. Then he got much, much worse.

He stayed with me on weekends, and twice during the workweek he would come to my house for dinner. We would sit at the table -- my husband (his stepfather), his brother and sister and I -- but my once-reserved older son would only stand over us acting crazy. Humming, shifting foot to foot, screaming if anyone touched him or tried to move him to the side. Often, he would talk back to the people who were speaking to him inside his head, telling him to do things. He would not, however, say a word to us.

He wasn't eating meals. But he was eating -- constantly. After graduating from high school, during the period when he was still holding the voices at bay, he'd started a government job through a disability work program. I'd given him a car and helped him open a checking account during this period of lucidity. Now, he began stopping at fast food restaurants on his way home from work to consume nachos, burgers, brownies and lattes. He ate with his hands and wiped them on his clothes, which he'd quit washing. He stopped bathing altogether.

We discontinued the Abilify, tapering it off as directed. Two days after taking the final pill, he got out of bed at 2 p.m. and stood in one place for a solid hour. My husband had taken our daughter roller-skating; our younger son was at work. It was just me, alone with this 6-foot-3-inch man I'd given birth to but no longer knew. I put my hand on his back and tried to push him forward, toward his shoes. And he turned to look at me -- his eyes empty and cold -- then grabbed me by both arms and beat me until the neighbors heard me screaming and called 911.

You think you know what crazy is, but you don't. Not unless you've been there.

In the movies, it might be depicted as quaint or flat-out violent. But whichever way it goes -- Hannibal Lecter or the wacky old ladies of "Arsenic and Old Lace" -- crazy is portrayed as consistent, interesting, narratively coherent. Not so in life.

In reality, crazy is like war. It's tedious for long periods of time, until it turns around and is devastating. It's random, senseless, all-consuming, financially draining, destructive, ugly, sickening and gross.

It's standing in the front yard wearing nothing but torn underwear and trying to control the thoughts of people who drive by. It's saying yes to every question, no matter what the real answer. It's drinking compulsively, straight from the faucet, then spewing a stream of clear-water vomit like a geyser.

It's needing to be tracked down at 5 a.m. and being found, more often than not, at a 24-hour convenience store drinking free coffee and eating package after package of mini-doughnuts. It's getting escorted out by security guards after hanging out at Target for nine hours. It's standing directly in front of a childhood home and swaying until the people inside, the ones who now live in the house, call the cops.

For the people who live with crazy -- who love crazy -- it means answering the phone over and over to say, "Yes, I'm so sorry, where is he? Please don't do anything yet. I'm coming." It means never finishing a movie or a book or a television show. Never eating a meal in peace. Suggesting showers that won't be taken and changing shit-stained sheets and throwing away clothes that have become too soiled to wash clean. And it means going to bed each night with a queasy feeling that something is looming over you, left undone.

It's paying over and over: for the library books that were lost, the iPod that was worn in the shower, the high-priced vitamins and health foods, the therapies and lessons and groups that are supposed to help but never do. It's including crazy on every family outing even though you know how it's going to end because it's the least wrong thing to do in an equation that contains no right.

It's also watching people you once loved fade away. Answering their periodic phone calls, full of concern, all their questions about what you've done already and what you're planning to do now, which medications you've tried, why you haven't called the doctor they recommended, whether you've read "Dear Abby" today where a letter about something remotely similar appeared.

But it's knowing, too, that after the phone call, they'll be gone. You won't be asked to the next neighborhood get-together or family event. They're worried, yes, but they can't let their lives be interrupted by crazy. They have to maintain their own sanity and keep the chaos from mucking up their lives, even if that means letting you go, too.

And you understand, only you don't. Because you'd like to be done with crazy yourself. In fact, you hunger for it. A full night's sleep, a meal by candlelight, a midnight drive across town that doesn't include peering out windows, scanning the dark streets for a mammoth, curly-haired young man in a green sweat shirt carrying a Styrofoam cup of coffee who sways back and forth as he mutters strings of remembered conversations under his breath.

Sometimes you wish for these things so hard that you ask yourself, "How badly do you want this to be over? And what, exactly, are you willing to do to end it?" You hate crazy with all your heart. But the person underneath, you love. You still remember him as a tiny, big-eyed baby who liked to be wrapped tightly in a blanket, a cheerful toddler sitting high in the seat of a grocery cart chanting the word "asparagus." And you'll stop at nothing to find him and bring him back.

The thing is: You have no idea how.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

We lived like this for as long as we could, then went back to the team of specialists with our story. Our son wasn't schizophrenic, we insisted. The medication they'd prescribed seemed to be harming him and our son was getting worse. But they told us we were wrong.

A second psychiatrist was called in. "Your son is definitely psychotic," she said, using the violence as evidence that we were wrong to have stopped giving him the drug. It was possible, however, that he needed something stronger. So this time, she prescribed Abilify's big, hulking chemical cousin: a pill with a no-nonsense name that makes it sound like a building material of some kind. Geodon.

"I'm sure you thought you were doing the right thing," the psychiatrist said in a stern voice. "But your son is very sick, he needs treatment. You absolutely must give him this medication. It would be cruel not to." And then she left.

That's the day I decided I was a terrible mother who deserved to be beaten. Out of fear and shame and denial, I'd withheld a medication my child needed as he would have needed penicillin were he suffering from an infection. "Go ahead," I told my ex-husband, "give him the drug. Let's hope this one works."

That's when things got really bad.

Our son went from unpredictable to entirely random. He would arise to brew and drink an entire pot of coffee at 3 a.m. He would call us, but be able to say nothing for 15 minutes except, "Uh, please..." He began stalking the girl from the dance, going to her workplace, standing in one place for hours, and staring at her. Ultimately, every officer in our town's small police department learned his name.

After two weeks, psychiatrist be damned, we discontinued the Geodon, too. Things couldn't get worse, we told ourselves. But we were wrong.

Our son, the former chess champion and 1980s music buff, stopped responding to language altogether. He could not follow directions such as: "Put on some pants" or "Get in the car." And he began walking away from everywhere. From home, from work. Often in the middle of the night.

My ex-husband -- newly married to a very understanding woman and blissful for all of about seven minutes -- never slept because he was working day and night to keep track of our son. I didn't sleep out of solidarity. Also due to worry and grief.

This turned out to be a good thing, however, because I was up all night, for many nights in a row, with nothing better to do than search online.

The first thing I found was a list of "infrequent" side effects of the very first drug, the antidepressant he'd been given nearly two years before. Among these: auditory hallucinations, narcolepsy and obesity.

The second was an obscure article about a boy who sounded exactly like my son: a high-functioning young man with Asperger's syndrome who'd suddenly become nonfunctional at the age of 17 and was diagnosed with something called autistic catatonia.

It was 3 a.m. and I was on the couch under a blanket with my dying laptop, alone in the silence of a sleeping house. That's when I Googled "autistic catatonia" and hit the mother lode. There were dozens of stories, coming from countries all over the world, and each one described in wretched detail the previous year of my son's life: the slowing, the disintegration, the delusions and insomnia and explosive anger.

In addition, they all warned -- each and every journal article, white paper and scientific treatise -- that the one thing practitioners should never do is prescribe antipsychotic medications, such as Abilify and Geodon, because they will make the symptoms of autistic catatonia much worse. And it might cause permanent damage.

The third thing I found was a Web site that described neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a slow poisoning by prescription that lasts (and this is the part that caught my attention) even after the drug is stopped.

Finally, believe it or not, we've reached the hopeful, lucky part. Only I didn't know that yet.

I was crazed. Throughout the early morning hours, I e-mailed people. The retired doctor from Stony Brook, N.Y., who had authored original work on autistic catatonia; a therapist from the Netherlands who claimed to have a new method for treating it; researchers at our local university. Then I went to bed and slept fitfully for exactly one hour and 40 minutes.

When I awoke, at 7:30, my e-mail box was full. The most helpful response came from the gentleman once of Stony Brook, now professor emeritus of both psychiatry and neurology, a genuine mensch, living on Long Island with his wife. "Dear Mrs. Bauer," he'd written at 6:48 a.m., "I know of no one in Minneapolis who understands the connection between autism and catatonia. But the clinicians at Mayo are very knowledgeable. Would you like me to make a referral?" Other messages simply advised me to seek medical attention for my son immediately, to flush the medications from his system. "It sounds as if your son is, indeed, suffering from autistic catatonia," one doctor wrote. "But I believe most of the symptoms you describe are related to the inappropriate use of neuroleptics."

How lucky can you get? Not only did the world's top expert reach across electronic airspace to help diagnose and refer a stranger, but we happen to live just one hour and 15 minutes from Mayo Clinic, one of three places on earth where autistic catatonia is truly understood. And it's that rare healthcare organization where doctors are not allowed to take kickbacks from the drug companies. But I'm getting ahead of myself.

On April 30, my ex-husband and his wife put our son in the back seat of their car and drove like hell the 72 miles to Rochester, Minn. Exhausted after the 90-minute trip, the three-hour wait to check in, the half-year of tracking a drug-addled boy, they walked across the street to a hotel room after checking him into the hospital and had their first uninterrupted night's sleep in weeks.

We all did. Secure in the knowledge that the boy who'd been wandering for nearly two years was finally locked up and safe, my husband and I, too, slept the way starving people eat.

Then we drove to Rochester to meet with the nine practitioners who'd been called in to assess our son. It was an interesting case, they told us -- and instructive. Within three days, they'd performed a series of medical tests and evaluations, determining that our son was neither schizophrenic nor psychotic. He was autistic, exhausted, improperly medicated, borderline diabetic, and simply stuck. It would take them perhaps a month to detox his body of all the drugs and treat the underlying catatonia that had dogged him for more than a year.

"This occurs in about 15 percent of all young people with autism," the team lead told us. "We don't know yet why it happens, but we can treat it."

And then they did. Magically, it seemed. On the morning after they began their regimen -- a combination of therapies that they orchestrated like a carefully choreographed dance -- our son awoke and stretched, clear-eyed, to ask us if we'd like to play a game of hearts. And after a slightly shaky start, he shot the moon, gathering all the tricks with controlled sweeps of his right hand, flashing us a shy but satisfied smile.

Five days later, the New York Times ran a front-page story about psychiatrists in Minnesota who were collecting money from drug manufacturers for prescribing atypical antipsychotics, including Abilify and Geodon. According to the Times, "Atypicals have side effects that are not easy to predict in any one patient. These include rapid weight gain and blood sugar problems, both risk factors for diabetes; disfiguring tics, dystonia and in rare cases heart attacks and sudden death in the elderly."

Side effects like our son's -- almost certainly caused by a unique combination of the drugs and autistic catatonia -- were not explicitly cited. These facts, however, were:

"In Minnesota, psychiatrists collected more money from drug makers from 2000 to 2005 than doctors in any other specialty," the Times reported. "Total payments to individual psychiatrists ranged from $51 to more than $689,000, with a median of $1,750. Since the records are incomplete, these figures probably underestimate doctors' actual incomes."

By this time, we four parents had resumed our life in Minneapolis and were trading visiting days.

After work on the night the Times article came out, my husband and I got on his motorcycle, puttered through rush hour traffic, then sped down Highway 52, arriving after the dinner hour to find our son sitting at a table, playing chess with a nurse. She was hunched over the board, muttering; he was lounging in his chair, leaning back to watch television while he waited for her to make her move. There was a small crowd gathered around watching.

"He's killing her!" a patient named Richard crowed. "He beat her the first time in seven moves and the second time in four."

The nurse raised her head and grimaced.

"Did you tell her you used to be a tournament player?" I asked, bending to kiss my son's woolly hair.

"Oh no, I guess I forgot," he said vaguely and slid his eyes at me in a way I recognized from years ago, that quirky boy from long ago.

After the visit, riding home through rolling farmland and a scarlet sunset that was cracked with gold, I counted the ways we were lucky. The doctors at Mayo had assured us that our son's prognosis was very good: Even after the treatment was done, he probably would continue to improve and regain most of the ground he'd lost by summer's end. My son's supervisor -- a wise and gentle woman who'd never flinched, even when he was at his craziest -- had called to say she was holding his job for him, maintaining his health insurance, and hoping for his swift recovery. My husband and my former husband's new wife had parented stalwartly through the very worst of times.

And there was that one moment, as we were leaving, when my son had put his hand on my arm and told me he missed us. He also missed going to Starbucks and walking in the sunshine and he wanted, more than anything, to go outside for just an hour or so. "You could just lead me out of here," he'd said, his face sober as a Lutheran minister's. "If I walked past the desk with you, maybe they wouldn't even see." I looked straight up at him, this bearded man who, at 250 pounds is exactly twice my size, and started to tell him I thought the nurses probably would notice. But he reached out and touched my arm, gently, wrapping his fingers all the way around. "I would only go out for a little while, you know. And later, I could come back. Don't worry, Mom. I can find my way."

Shares