Shielded by a January fog, 13-year-old graffiti writer Ari Kraft sneaks through a dilapidated chain-link fence to tag railroad signal boxes. Later that afternoon, the hum of rush-hour conversation aboard the eastbound Long Island Rail Road train to Huntington, N.Y., is pierced by the sound of screeching brakes and an exploding spray paint bottle. Kraft, trying to rush across four sets of tracks to make it to a Sabbath dinner with his mother, only makes it across three.

The next day, as the shock of the tragedy sets in with Kraft's tightknit community in Rego Park, Queens, the teenager's picture appears on a Web site called MyDeathSpace, along with an article about his death and a link to his MySpace page. Kraft's information is featured in a gallery of similar real-world fatalities on MyDeathSpace, which connects its audience not only to news about recent deaths, but to the MySpace pages of the deceased. Just below the cartoonish skull logo and tombstones that are prominently branded on its front page, the site promises "one death or suicide an hour."

Most of the victims listed are in their teens or 20s, and each is memorialized according to the same standardized format: with an unattributed news story, an obituary (or in some cases, a blog entry that details the circumstances surrounding the death), a photo of the victim, usually culled from a once-active MySpace account, a link to the MySpace page, and a discussion board link at the bottom.

When a person dies, his or her MySpace page and its assortment of photos, blog entries, songs, videos and other digital ephemera becomes a de facto shrine to the deceased -- teenage life's trivialities, dilemmas and existential crises packaged and displayed as a neat narrative.

That narrative may continue well beyond death if victims have left their message boards open to the public, as friends, family members and even strangers add comments to the page. (MySpace's default configuration allows comments to be posted without a user's preapproval). The MySpace version of one's life story even has a soundtrack, depending on whatever death metal, hip-hop or emo track users choose to embed in their profile. For some, it's a form of reality-based entertainment, of the most morbid variety. MyDeathSpace's avid fan base scours the news for recent tragedies and keeps the site current by submitting deaths for consideration.

By evening, total strangers have already visited Kraft's MySpace page and begun chiming in on his discussion board. The conversation begins with an indignant salvo.

"Come on," writes a person identified only as "andrea0121." "I know when I was 13, my parents pretty much knew my every move. I certainly wasn't hanging out on train tracks spray painting shit. Here's my lesson for the day kids, DON'T PLAY ON F'ING RAIL ROAD TRACKS."

Another user, "Dopey," is intrigued by the items Kraft's friends have been posting on his public message board back at MySpace. "[Kraft's] mother is Israeli-born, his name is Ari, and his friend says 'RIP Nigga.' I'm so white, and so old, and I so don't get it. Sigh."

Things get cruel quickly. Not even two days after his death, a MyDeathSpace user writing under the moniker "Morbid Curiosity" (real name Terisa Davis) offers up a joke. Many graffiti writers are known by the pseudonymous "tags" they spray on walls and other public areas. "I think I found his tag: 'Dead,'" Davis writes in sparkly, glitter-painted font. Getting the comment past the forum moderators ostensibly responsible for removing offensive content from MyDeathSpace wasn't difficult in this case: Davis is a forum moderator, one of five who volunteer their time patrolling the message boards.

A 15-year-old girl who claims she was a friend of Kraft's tries to muster up a defense. "His death, just like any death should be respected and because he isn't here to stand up for himself shouldn't be criticized," she writes. Brave and earnest as she may be, she's not likely to sway any opinions. Forum members had already ridiculed her for misspelling "jaywalking" in an earlier post.

"If someone told you that life is fair, they lied," another moderator who goes by the name "daybreakdisdain" finally tells her.

"Life as a whole might not be fair," the young girl writes back. "But other people can make it more tolerable."

MyDeathSpace is the creation of Mike Patterson, a 26-year-old San Francisco paralegal who holds a bachelor's degree in English from UCLA. Patterson claims he created the site to teach teens a "lesson" about risky behaviors, especially when it comes to driving automobiles. The idea came to him, he says, after reading about a Bay Area murder in which a man killed his wife and two daughters before committing suicide. He wondered if the two girls had MySpace pages. They did.

An early incarnation of the site (on a LiveJournal blog Patterson maintained) attracted between 3,000 and 4,000 users (as well as intermittent complaints) over the course of its four-month life cycle. If Patterson's motivations were altruistic, he revealed them in peculiar ways -- site graphics included a melodramatic photo of a white, middle-aged man being strangled; a tag line read "Myspace Deaths! We need to cut back anyway." Bringing his active readership along with him, Patterson launched MyDeathSpace in January 2006.

Today, MyDeathSpace claims more than 8,000 registered users. Registration allows members to receive notification of new deaths by e-mail, chat electronically with others, and most important, post on the discussion boards. Others sign up to become premium members, which grants them access to new deaths 24 hours before they become publicly available, as well as "no ads or popups while browsing the forum."

What began as a platform for virtual rubbernecking took on new significance after the massacre at Virginia Tech University. The tragedy offered a glimpse of a new meta-reality: 17 of the victims had MySpace profiles, which mainstream press outlets eagerly scoured for information.

No organization was better equipped to handle MySpace-trolling duties than MyDeathSpace. The next morning, the New York Times blog was pointing traffic toward the site, described as specializing in "respects and tributes to the recently deceased MySpace.com" members. Tens of thousands flocked to it, and hundreds signed up for accounts, which allowed them to post in the discussion forums. Unable to handle the increased bandwidth, the server crashed.

Thanks to the work of its dedicated readership, MyDeathSpace had the most up-to-date list of Virginia Tech victims, scooping the mainstream press. "I don't want to say it was creepy, but it shows that a lot of people know about MyDeathSpace if they're actually submitting victims they know personally or friends of friends before it was mentioned in news outlets," Patterson says.

Twenty years ago, death was discussed in muted tones, the deceased treated reverently. An obituary usually announced a tragedy to the public and a guest book provided friends and loved ones with a limited forum for expressing condolences.

The Internet has changed all that. Online, where pseudonymous message boards flourish, the response to death is more like a free-for-all than the respectful hush of yore. It's not just MyDeathSpace. Even forum postings on mainstream news sites can read more like angry restroom graffiti than even-tempered letters to the editor.

Message board culture is predicated upon a democratic relationship between media and consumer that makes information accessible on demand and provides readers with an instant platform. Find an attractive potential suitor on MySpace, and you can send the person an instant message or e-mail. Stumble across a band you like, and you can not only download their catalog on iTunes or eMusic but instantly make them your "friend" by sending out a simple MySpace query. Follow the premise to its logical conclusion and it doesn't seem so shocking that you can read about a sad death and join the grieving, or that you can hear about a particularly dimwitted cause of death and immediately jump into ridiculing the victim.

For better or worse, this is a new American way of death, where a MySpace page takes the place of your obituary and becomes fodder for worldwide forum banter. A person may die, but the MySpace page does not -- as a matter of policy, MySpace only removes inactive profiles at the request of a family member.

An active MySpace page is typically the only prerequisite to earning a spot on MyDeathSpace, which now lists more than 2,800 deceased individuals. Most are between the ages of 16 and 23. (MySpace officials would not comment on MyDeathSpace, declining to return repeated calls from Salon regarding this story.)

The more robust a victim's MySpace page, the more lively the MyDeathSpace discussion is likely to be. Occasionally, a MySpace page reflects the circumstances of a person's death with eerie prescience -- the photos of guns maintained by someone killed by a gunshot, the drug-related songs and movies enjoyed by a person who goes on to overdose, or the proclivities toward thrill-seeking professed by someone who dies recklessly.

People visit the site for different reasons. Kristy Olsen, an artist and mother who discovered MyDeathSpace last year and occasionally still peruses the forums without ever participating in the death discussions, admits, "I don't completely understand why I'm drawn to such a site -- it's a massive dose of sadness, but I know I'm not alone in my curiosity. I think everyone that's living is sometimes drawn to death, to see what it looks like, to be humbled." Olsen continues, "Most of the obituaries are such young people, and being a parent myself, that really tugs at my heart."

Others are like 20-year-old Amber Perry, a more active member from California who is studying to become a forensic pathologist. She considers the site to be a primer for her chosen career path, allowing her to exercise her investigative skills among a community of like-minded sleuths. Drawing inferences from "clues" left behind on victims' blogs or other online sources MyDeathSpacers seek out, she and the others attempt to deconstruct the emotional state of someone who has committed suicide, for example, or unravel the circumstances behind mysterious deaths.

Though she prefaces message board postings with an obligatory "rest in peace," Perry says she's more than happy to "put a theory out there" if something about a death's circumstances doesn't seem to add up. Asked why she thought she or anyone else had a right to pry so deeply and comment on the death of a stranger, Perry admitted this was "a good question," though she fell short of an answer. "I don't know," she says. "I just like to put my opinion out there."

Taken as the cautionary tales Patterson says he envisions, the collected tragedies are chilling. After all, the young rarely die of natural causes. They die of suicides and murders; of daredevil stunts involving moving trucks and merry-go-rounds; and, of course, alcohol and drug overdoses. One 21-year-old soldier discussed was found dead after drinking Southern Comfort through a funnel.

"It does teach a valuable lesson ... it's amazing how many young lives are taken away by ignorance, drunk driving and suicide," 25-year-old Valerie Taylor writes in an e-mail. A self-professed horror movie fan, she's been a site member since its earliest days and is known online as "Paranoia Agent."

Perry, who discovered the site four months ago, says that her initial reaction was, "'Wow.' These kids are just living their life and 'bam' -- something crazy happens."

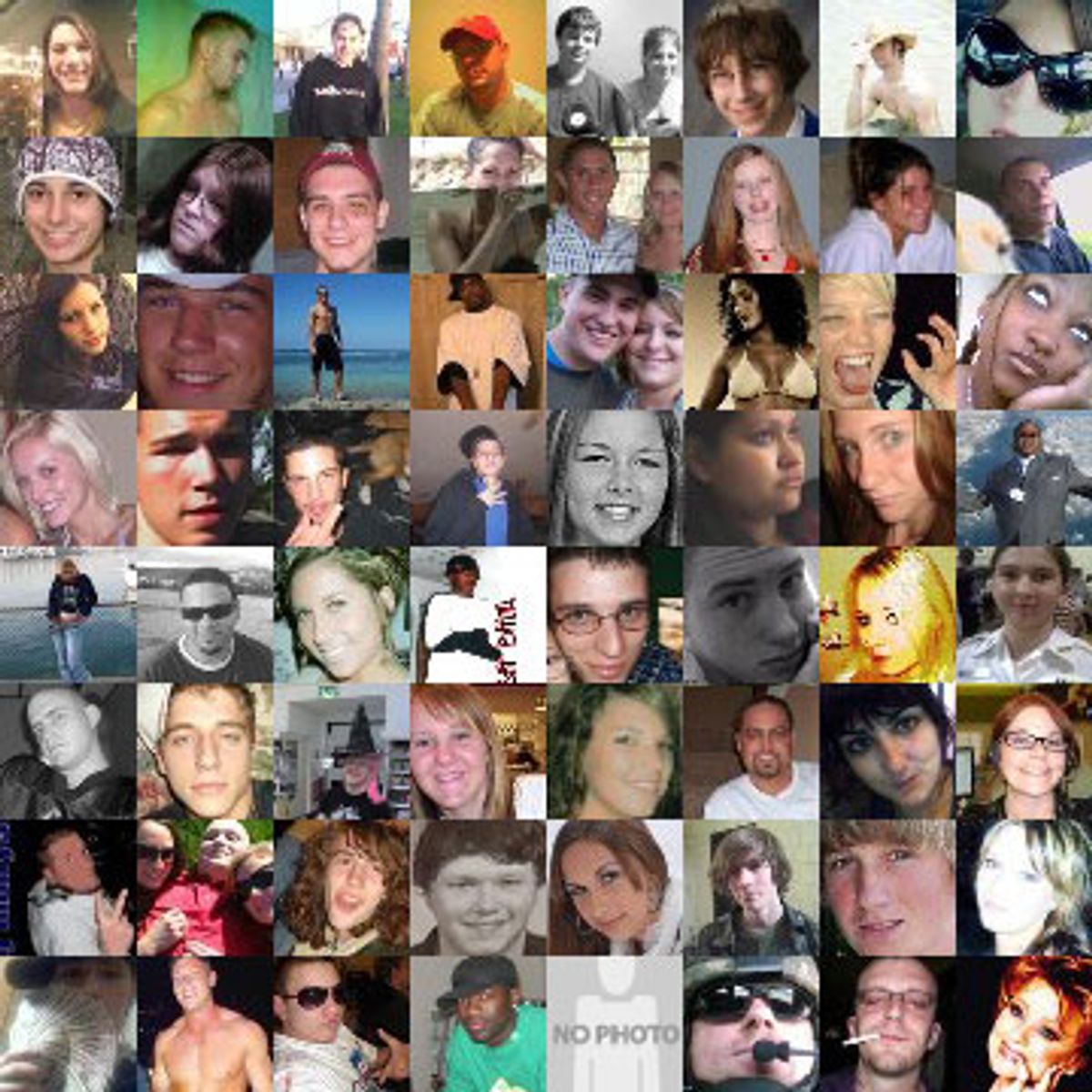

Patterson doesn't keep track of the ages of site members, but he says women outnumber men 2-to-1. Judging strictly by the photos posted by users in the galleries -- an admittedly unscientific sampling -- the core audience seems to be teenagers and 20-somethings. Site detractors enjoy dismissing the regulars as "emo" kids, a stereotype that both irritates and amuses its loyal base.

Davis, a 38-year-old art director from Dallas, says that the photo galleries underrepresent older users. "They're not trying to get laid," she laughs. It's true -- even in death's shadow there is time for member cleavage shots and flirtation on the message forums.

For Davis, the fascination with death precedes her involvement with MyDeathSpace. After 9/11, she flew to New York. After the Columbine school shootings, she became "obsessed" with following its media coverage. Though personal obligations have diminished her site activity (she's averaged about 20 postings per day since last July, while another site-generated statistic tallies her total log-in time at 52 straight days), she still helps moderate the forums and posts comments on strangers' deaths. She says of her message board activity, "It's online. It doesn't always seem real to me because I didn't have a connection with [victims]." On the other hand, "If it is someone I know -- if it is 'real life' -- I am not cold or callous about it," she says, remembering how much she cried after hearing about a friend's brother who died in Iraq. On occasion, parents of MyDeathSpace victims have reached out to the forum moderator, which sometimes "freaked" her out. "I do feel sorry for them," she says. "I don't want to be involved in exacerbating their pain."

Grieving family members aren't always embraced warmly, though. A woman identifying herself as "TarasMom," the mother of a murdered grandson and daughter, posted in a forum last August, warning users that their barbs toward the dead "cut like a knife."

Members responded in caustic fashion. "I am sorry about your loss, but this is AMERICA, land of the free," wrote one user. "Dead people don't need mothers and I'm sure there has to be something about you more interesting than being some chicks [sic] mom. Why not move on?" another added.

While some have written to Patterson threatening to sue MyDeathSpace or have the site shut down, there is little First Amendment basis for actually doing so, according to David Hudson, a research attorney with the First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt University. After all, MySpace profiles that are open to the public effectively become public information. And legally speaking, it is impossible to defame a dead person. So far, the site has yet to meet a legal challenge.

Visitors who write Patterson e-mails critical of MyDeathSpace run the risk of having the text of their e-mail (and oftentimes, their e-mail address) publicly displayed on a "Hate Mail" discussion thread. Members often respond by trolling the Internet for facts or photos about the complainant in order to post them. Salon contacted several people who are critical of the site, but none would speak for the sake of an article, fearing repercussions by the MyDeathSpace community.

Patterson argues that if you don't like the site, don't come to it. But tell that to those who arrive at MyDeathSpace inadvertently, having Googled the name of a deceased friend or relative. Nevertheless, Patterson respects the wishes of family members who want to have a child's MyDeathSpace profile deleted, except, he says, in the case of convicted murderers.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Patterson packs MyDeathSpace with advertisements for dating services, death-related sweepstakes and merchandise, and even a graphic video of animal slaughter courtesy of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. So far, the organization's investment has paid off -- about 500 MyDeathSpace users have signed up to receive PETA's "vegetarian starter kits," according to spokesman Jay Kelly.

Though he charges both for ad space and premium memberships, Patterson says he doesn't "make any money" from the Web site. And even if he did, so what? Some of the site's defenders point out that morticians have long profited from death, as documented by Jessica Mitford's landmark exposé "The American Way of Death" back in 1963. And if people are going to criticize Patterson for profiting from the public's insatiable obsession with death, shouldn't they also go after Fox News, MSNBC and any other news outlet that fawned for weeks over the minutiae of Anna Nicole Smith's death and autopsy? As public platforms for expressing grief, MySpace memorials may be little more than the digital equivalent of inner-city graffiti memorials or curbside shrines. Still, all this intense focus on death makes some in the suicide prevention world nervous, says Christopher Le, resource and information manager for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. He worries about copycat suicidal behavior, a phenomenon known to social scientists as "contagion."

"Visitors to victims' MySpace pages might fixate on how much a deceased person is missed and say, 'I want to be missed just like this,'" Le says. He contacted Patterson last August in the hopes of securing free advertising for suicide prevention resources, but Patterson wanted compensation, just as he would from any advertiser, according to Le.

Patterson says the site provides links to suicide prevention hotlines and that he once intervened personally when he was contacted by a 15-year-old girl who implied that she was thinking of killing herself, asking the site administrator to save her a postmortem "spot" on MyDeathSpace. "At first, I thought it was a joke," he said. That was before she sent him her MySpace and Yahoo e-mail passwords, as well as the date she planned to take her life. Patterson says that he signed on to her MySpace account and looked at all of her outgoing messages. "She was literally saying 'bye' to all her friends." He says he contacted law enforcement officials, who tracked the girl down and saw to it that she received proper medical treatment.

Nominally intended to steer people away from dangerous real-world behaviors, MyDeathSpace remains an equally potent warning about the dangers of activity online. "Once you have a MySpace page, you've exposed yourself to be open to anything," says Amber Perry. Moderator Terisa Davis agrees, noting that she keeps her own MySpace blog postings private: "I don't necessarily want the whole world reading that."

Shares