About 10 years ago, I worked as a producer for Bryant Gumbel's newsmagazine show on CBS.

"I want to interview Evel Knievel," Gumbel told me. "Knievel's dying of hepatitis C from all the accidents and blood transfusions. And he wants to tell his story before he goes. I want you to produce it."

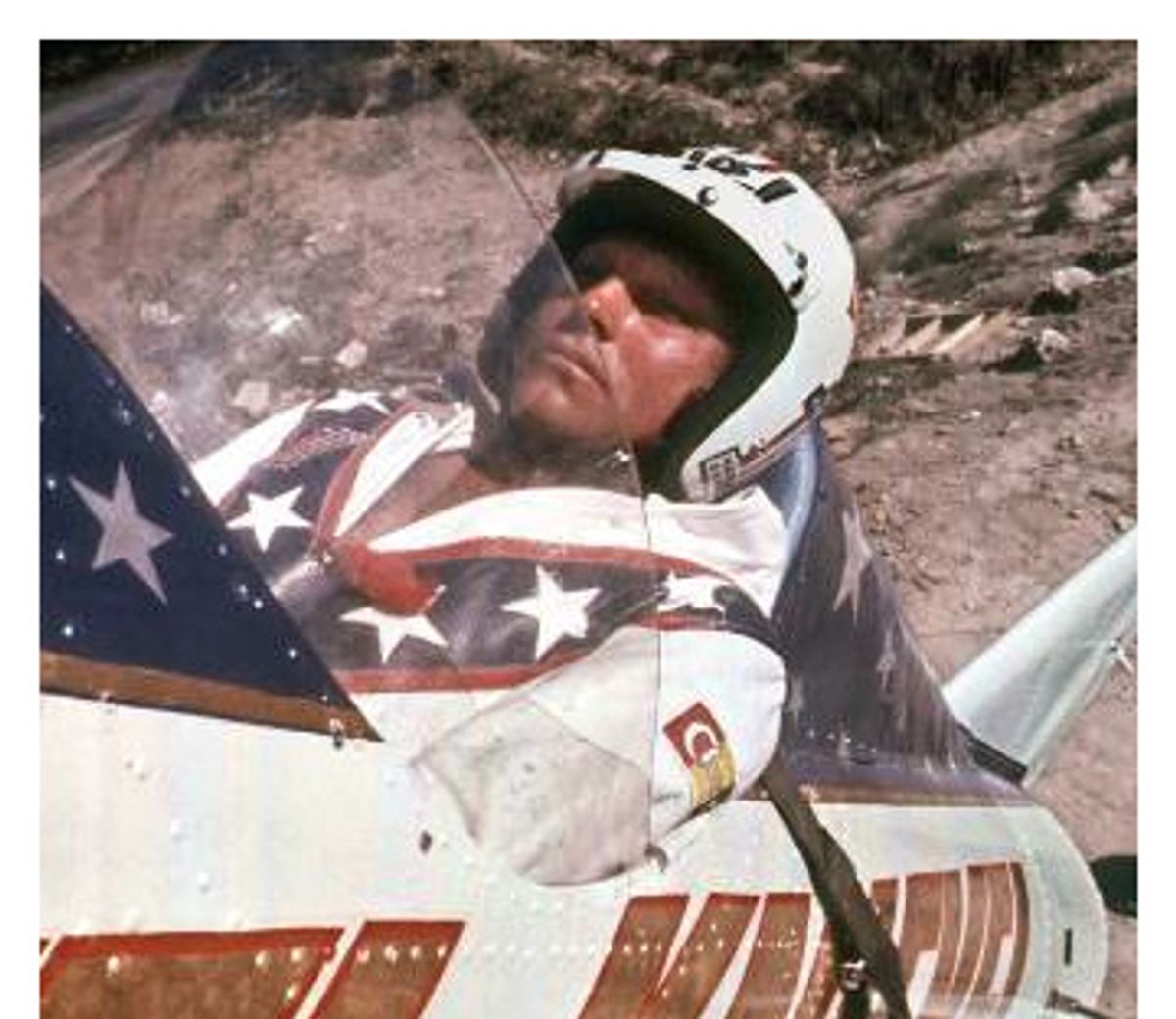

There was no need for Gumbel to convince me further. I could already picture the opening shot of my report. Two motorcycles would race down a sunbaked highway toward the edge of the Snake River Canyon, the site of Knievel's great failed jump, to the beat of Steppenwolf's "Born to Be Wild." The roaring of engines would grow impossibly loud as the bikes raced toward the cliff, and at the last possible moment, the figures would skid to a stop. The first man would slowly lift his dusty helmet and we'd discover it's television newsman Bryant Gumbel. There would be no need for the second man to reveal his identity. His blazing white Captain America jumpsuit with red and blue stars across the chest gives him away.

Bryant and Evel Knievel would be standing on the precipice. The two men would look silently, pensively, into this great abyss. Bryant might even take a pebble and casually toss it over the edge into the bottomless canyon. Then he would turn to Evel, lower his reading glasses, and ask the question that all loyal television viewers had come to expect.

"You've spent your entire life coming up with elaborate ways of thumbing your nose at death." Evel would nod silently.

"Looking back on it all, Evel, was it worth it?"

I sat at my desk with Evel's phone number in front of me, paralyzed by a problem that few other men have ever had to face: When you call Evel Knievel, what do you call him? "Mr. Knievel" sounded so formal and obsequious. It would immediately create a barrier between us. And if I called him Evel, I was sure I'd come off sounding like some hapless schoolboy clutching a life-size poster of the stuntman, hoping to get his autograph. In the end, I asked for Evel Knievel. What I got was the flat, dry voice of a frail sick man just awakened from a midday nap.

I apologized and told him the purpose of the call.

"This will be your chance to talk about hepatitis C," I told him. "A way to promote the issue and to help people." Evel explained that's exactly what he wanted to do. He needed a new liver and there was a good chance he would die. He joked that this was his latest stunt, something his doctor liked to call "Snake Liver Canyon." The problem was, Evel wasn't joking. As with all his other death-defying stunts, Knievel wasn't about to undergo liver transplant surgery for free. He wanted to be paid for it.

When I explained to him that network news does not pay for interviews, Evel transformed from lighthearted to angry. He referred me to his lawyer, Fred, and then he hung up on me.

Fred was an impatient man who quickly sold me three VHS tapes and one DVD of Evel's greatest stunts for 80 bucks.

When I explained to Fred we couldn't pay Evel, Fred began to yell.

"I don't give a goddamned about network rules," he shouted. "There's always a way to massage it."

Then Fred hung up on me, too. We had hit an impasse, but I had hope that once Fred cooled off, he'd come around and Knievel would do the show.

The next day, when I received a box with the three VHS tapes and the DVD, I invited friends over to watch Evel attempt his death-defying feats, in chronological order.

Within moments, they were cheering and laughing. Nearly every time, Knievel would crash, the pavement snapping and clawing at his leather jumpsuit, as he skidded and tumbled like a man with no bones.

We watched his 1968 Caesar's Palace jump as he crash-landed and went into a monthlong coma.

At Wembley Stadium, his crash broke his pelvis, but made him $1 million.

When he tried to clear the Snake River Canyon is 1974, his parachute deployed just after takeoff, and he ended up landing on the bank of the swirling river. Chalk up another $6 million for Knievel.

Evel Knievel was kitsch. He was an Elvis who couldn't sing. He was a stuntman without a movie. But none of that mattered.

As my friends cheered, I saw that Evel Knievel was a visionary. Decked out in his Captain America jumpsuit, he created the first and perhaps the greatest reality show of all time. He embodied the American dream: getting paid to take risks, and getting famous along the way. In less than 10 years, he made $60 million in exchange for 40 broken bones, multiple concussions and a coma.

The next day, I shouldn't have been surprised when Fred called me to decline CBS' offer to interview Knievel.

There would be no final interview, no talk about his attempt to beat hepatitis C.

We would never see that scene: Bryant Gumbel and Evel Knievel standing on the edge of the canyon. Bryant lowering his glasses and saying:

"You've spent your entire life coming up with elaborate ways of thumbing your nose at death. Looking back on it all, Evel, was it worth it?"

I suspect Evel would've answered, "Bryant, it was worth every penny."

This was a man who would do just about anything. But Evel Knievel never did anything for free.

A shorter version of this essay was broadcast on NPR.

Shares