To listen to a podcast of the interview, click here.

To subscribe: Click here to add Conversations to iTunes or cut and paste the URL into your podcasting software:

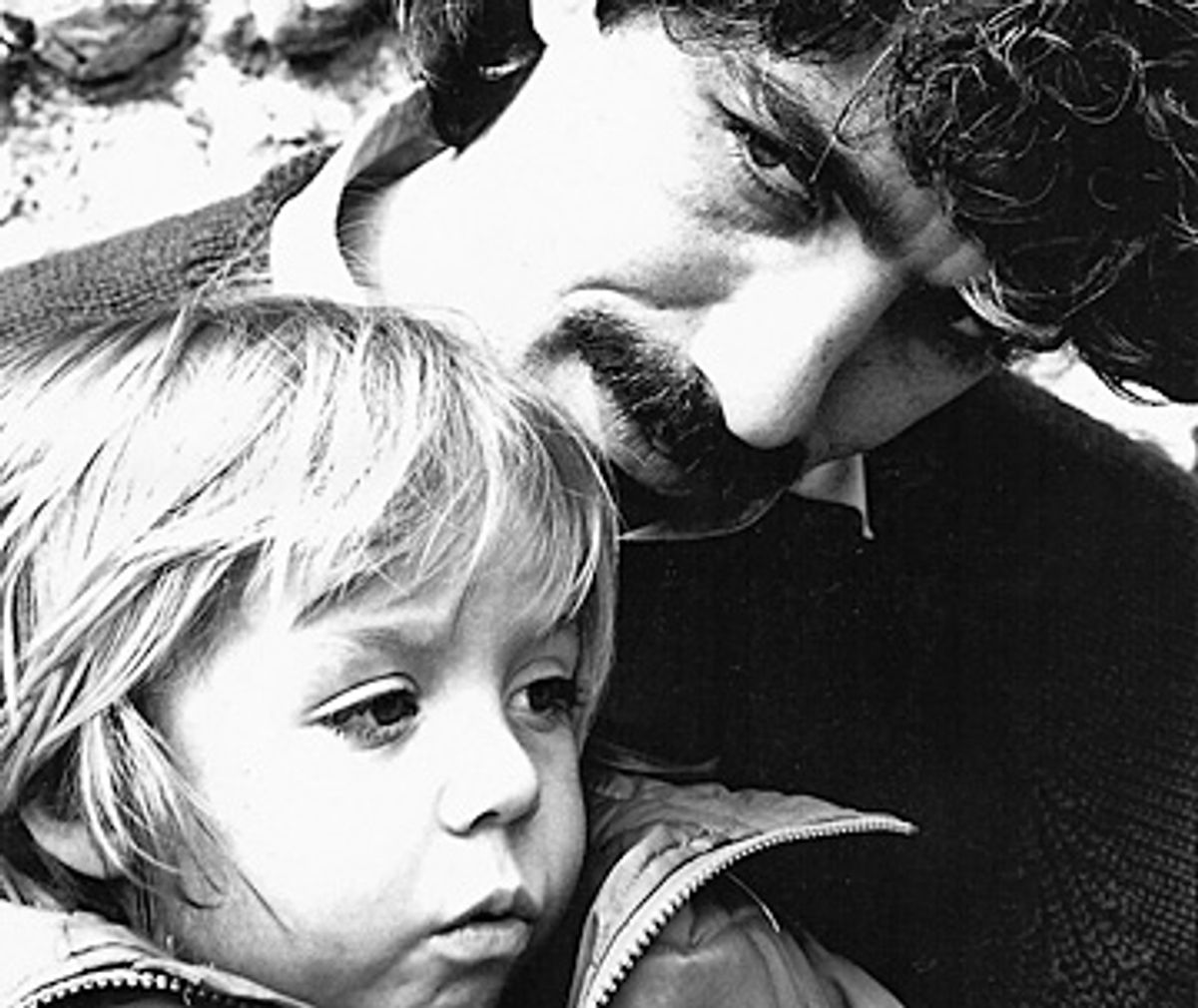

David Sheff watched his oldest son, Nic, transform from a happy kid who loved surfing with his dad into a meth addict who stole money from his 8-year-old brother. Nic broke into his father's house so often that, eventually, David installed a burglar alarm to keep his own son at bay.

David, a longtime San Francisco Bay Area journalist, struggled for years to help his son get off drugs and stay off them, all while enduring Nic's lying, disappearances, betrayal and terrifying close calls. Nic was arrested for possession in front of his younger brother and sister. He overdosed and was revived in the emergency room. Most heartbreaking, Nic went through rehab, got clean, returned to school or work and then relapsed, only to end up strung out on the streets again.

Meanwhile, David miserably second-guessed his own role: Was his divorce from Nic's mother (sparked by his infidelity) and their long-distance joint custody arrangement a factor? Or his own youthful history of drug use, which included snorting meth? Should he have forced Nic into rehab back when he was under 18, when his drug use had seemed more like typical adolescent experimentation? As the crisis stretched on for years, with the relative calm of Nic's periods of recovery colored by the ever-present fear that he'd relapse again, David had to struggle to keep his own obsession with Nic's addiction from dominating his life and the lives of his second wife and two younger children.

In 2005, David told their story in the New York Times Magazine in a piece called "My Addicted Son." In reaction, David received hundreds of letters from readers, an outpouring of their own similar sad sagas. Now, David, 52, and Nic, 25, who has been sober for two years and three months, have written simultaneously published father-son addiction memoirs. Nic's, called "Tweak," is a book for young adults that does not spare sordid details, including how he turned to prostitution for drugs and almost lost his arm to an abscess caused by shooting up. David's book, called "Beautiful Boy," is a father's agonized tale of watching his son deteriorate and get clean, alternating between the fear of losing his child and a stubborn hope that -- maybe this time -- Nic would finally stay sober.

Salon spoke with David Sheff at our offices in San Francisco.

How did you find out that Nic had a drug problem?

We were really close, and I thought it would mean that we always would be pretty open with each other. So I was completely shocked when he was in seventh grade, and I was looking for a sweater for him, and found pot in his backpack. He was just this little boy. I had no clue. But I met with his teacher, and I talked a lot to Nic about it. I thought it was just the product of being influenced by some "bad kids," some of the darker, more precocious kids in school, who were not his normal friends.

The next time it happened was at the end of his freshman year in high school. I got a call from the school, and they found him buying pot. He was kicked out for a day and forced to go into an afternoon drug rehab program. We came in and met with the counselor and the dean, and then he seemed fine for a couple of years.

Things descended when he was a senior in high school. Now, I look back, and I see the times when he ran away, the times when he stole stuff from us and from other people, his erratic behavior, weird hours he kept, the people he was hanging out with. Anybody else in their right mind, a sane parent, would have looked at him and said: "You know, he's having trouble with drugs."

I kept explaining it away and thinking he was just rebelling a bit. Normal adolescent stuff. It wasn't until he graduated from high school, and went to Berkeley, that everything just spiraled out of control. He started using methamphetamine. Then, it was no longer a question. He was disappearing for days at a time, and when I finally found him he looked like he was ready to die. It became clear he had a problem I could no longer ignore.

Back when he was in high school, didn't counselors and psychologists affirm your view that he was going through a typical rebellion and that he would get through it?

When I brought him to therapists, and I brought him to counselors, the consistent message was that he's going to be fine: Kids do this. He's experimenting with drugs.

Nic said: "I'm not stupid. I'm not going to do anything stupid. Everybody I know smokes a little pot." And even when things escalated to the point where I was concerned, and I did go see specialists, it was always minimized.

In hindsight, do you think that, given who Nic is, the only way for him to avoid addiction was to never try drugs at all?

Like Nic, if you've got the genetic piece, and the psychological piece, and other mental health issues, your predisposition is such that any use will probably lead to problematic use. Whether it will go as haywire and out of control and dangerous as it went for Nic, that is unknowable in any particular individual.

Nic was destined for this. He was just drawn to it, even intellectually. He loved the dark stuff. Reading Bukowski and Burroughs and Henry Miller doesn't necessarily mean that a kid is going to try to emulate their debauchery to the point that Nic did, but he really was fascinated by it. For him, it was about being cool, it was about being an artist, it was about being on the edge.

Do you think that your experiences with drugs made it harder for you to recognize that Nic had a problem?

My experiences both made it harder to recognize that he had a problem and more scary for me. I used a lot of drugs, but I was not addicted. I was the guy in college who would be at a party getting wasted with all my friends at 2 o'clock in the morning, but I would say: "Oh, it's 2 o'clock in the morning, I've got to get up for class in the morning. Goodnight." And they would look at me like I was from Mars, especially my roommate who went on to be a heroin, meth and cocaine addict.

I know that you can do drugs, and they don't necessarily destroy your life. Although I definitely did things that could have killed me, I was lucky. I do know that some kids do experiment with drugs, and they move on. I wanted to believe it [was true for Nic]. On the other hand, I had seen so many victims.

Once you started looking into rehab for Nic, you found there is a really high relapse rate for meth. Do you feel like that's a problem with the programs, or is that a testament to how hard it is to get off the drug if you're addicted to it, or both?

I think that it's both, for sure. I thought, naive and hopeful, that I could send Nic to rehab, and I would pick him up in 30 days and he'd be cured. It would be over. What I now know is that addiction is a chronic and progressive illness that requires a trajectory of treatment, which sometimes can mean multiple rehabs.

A nurse told me that probably nine out of 10 kids who come in using meth will relapse. If you measure longer term, the relapse rate is lower. So the success rate is somewhere around 50 percent for people who are engaged in rehab over the course of years. And so it wasn't as bleak as it sounded at the beginning.

I was getting calls from some people who were longtime sober, who said to me, "You just have to let him go. He has to hit bottom. He has to figure it out. He has to want to live more than anything." But then I got a call from a mother who heard that we were going through this, and she said, "My son is now 30 years old, and he's been sober for five years, but before that he was in and out of rehabs and treatment centers and hospitals and detoxes 10 times, and if I didn't send him that 10th time, he would be dead now, and he will tell you the same thing. So all I can tell you is: Don't give up on him, and do everything you can."

When you were going through this, it seemed like you would get a lot of well-meaning advice that was 180 degrees contradictory. What advice helped you the most?

The advice was tricky, because if somebody told me what I wanted to hear, I would embrace it, because I was so scared. I was so afraid that he was going to die. If somebody told me to go find him, when he was on the San Francisco streets, I would get into my car and go do it.

Every impulse I had was to go try to find him. It's sort of a scene from a bad movie. I would go out and scour the streets of San Francisco, and it was a ridiculous thing to do. The chances of finding him were pretty slim. And if you find somebody, and they're high on drugs, and if they don't want to go into treatment -- Nic's an adult, he's over 18 -- there's not much you can do about it. To try to help somebody who doesn't want to be helped is ludicrous. It doesn't work.

I guess the best help that I got was when I finally was directed to Al-Anon meetings, and I was with people who had been through what we were going through, but who weren't trying to tell me what to do. They were only telling me what they had been through, and all of a sudden I realized that I wasn't so alone, and that was enormously comforting.

What is it about methamphetamine that makes it so addictive?

Researchers who study this have shown me pictures of what happens inside the nervous system. The methamphetamine molecules hook onto the receptors in the brain differently than any other drug. If somebody does cocaine, the body can break it down and diminish the impact over the course of about 45 minutes or an hour. Methamphetamine blocks the system that normally would do that. Methamphetamine stays active until the drug itself breaks down, about 12 or 14 hours. The physical impact is dramatic.

There is also an equally destructive emotional factor that kicks in because the drug causes this outrageous pouring out of dopamine and other neurotransmitters -- all drugs do that, but the volume is just greater with meth -- and depletes the body's ability to regenerate them. The methamphetamine high is the greatest thing in the world because you're using up all of those chemicals that make us able to feel good, feel happy, feel all of the positive emotions that we know. But then it's gone.

When you come down from methamphetamine, the feeling is so bleak and so haunting. It's depression, but it's depression that I think is inconceivable for somebody who hasn't done it. It's just so dark that you then will do anything you can do to feel better. And the only thing you know how to do at that point is to get more meth, and so the cycle kicks in.

With methamphetamine the first weeks of withdrawal are characterized by depression and anxiety that are both off the charts. It's emotional with a physical basis. In other words, someone is feeling so bad, and they can't sit still, and the one thing on their mind is that they want more drugs.

The scans of meth addicts' brains look normal again, but not until two years have passed. After two years the prognosis is better partly because of all the other things known about recovery and treatment, but partly also because the capacity [to recover] is back.

When Nic was going in and out of rehab, what did you feel like you were able to do to help? And what could you really just not do?

Well, it changed. I played the game with Nic. He would tell me that he was doing better. I would want to believe it so badly, I would say, "Oh, thank God. Sure, you can come home." And then he would steal stuff from us again. He would say, "I'm just going to A.A. meetings, can I borrow the car?"

"Oh, sure Nic, as long as you're in recovery, that's really a good, wonderful thing. I'm so proud of you. Sure, take the car." Until he would do that for three or four nights in a row, and then he wouldn't come back, and it finally dawned on me that, well, maybe he wasn't going to A.A. meetings, he was going to the Tenderloin in San Francisco or going to Oakland to his dealers' and he was scoring and using drugs with his friends.

I learned the hard way that there was only one thing that I could help him do. It was to wait for him, basically, until he was willing to go into a treatment program. That was hard, because there were times when he would call me up, and I would be in anguish, and all I wanted to do was go get him, put him in my arms and take him home, but I would say, "Are you ready to go into a program somewhere? I'll pick you up and bring you right to a program. I'll find someplace."

And he would say, "No. I don't need that. I've done that before, it doesn't work for me. I'm not going to go to one of those places. It's all bullshit. They're just going to shove A.A. at me, and I don't believe in A.A."

So I would say, "Well, Nic, I'm so sorry, but I love you and call me when you're ready to get help." And I would hang up the phone, and I would just weep, because that's not what I wanted to do. Every impulse was to just say, "Anything you want. I'll come get you. I just want to see that you're safe."

You wrote that you came to think of him as two people, and that helped you cope. How did you learn to think of him that way?

One of the times Nic relapsed, I thought he was sort of pulling it together on his own, and he called me up and he told me this elaborate lie, "Hi, Dad, I'm doing better now. I'm out in the desert with my girlfriend, and I'm sitting here under a tree writing."

Only later I found out that he had made that call from Oakland, and he was on crack. Somehow that moment I was able to fathom what was happening to Nic, to me and to our family in a new way, which was that Nic on drugs was a completely different person than the Nic that I knew and loved and raised.

Now, I certainly am enormously hopeful. Nic seems great. He doesn't have any false illusions about himself. But we both live with the specter of his addiction over us, and probably always will.

There is so much shame around addiction. Not only the addiction itself but all the associated behavior, like the squalor and the stealing. Were you reluctant to tell your family's story so publicly?

I was reluctant. At first I didn't tell anybody when this was going on, and it was because of the shame. It wasn't so much that I was trying to protect myself, but I was trying to protect Nic. I didn't want people to think badly of my son, my lovely, perfect, beautiful boy son. I just didn't want people to think of Nic differently.

I read other stories of addicts and alcoholics, like Thomas Lynch's "The Way We Are." They always helped. I finally stopped worrying what people would think. I found out that almost everybody has some secret, some dark fear that if people knew this about them they wouldn't like them anymore, or would look down on them.

What I learned is that really the opposite is true. The more I tried to keep this a secret, the more I was in turmoil. I'd try to show this exterior to the world that everything was fine with our happy family, our little kids, Nic's off doing something, while inside I was dying.

I finally realized that I couldn't keep it a secret any longer. At one point, it just sort of spilled out. I was less sick. It still didn't solve the problem. But when I started to tell people about it, I would hear this outpouring of emotion and acceptance.

What was it like to read Nic's story of his addiction? What most surprised you about the experiences he described?

The reality was so much worse than anything that I had ever imagined. It was so hard to read. Everything from the dangerous situations he got into because of the whole drug world, dealing with dealers and addicts and stealing money, robbing people, prostituting himself to try to get drugs and money.

I have this image of this child in my mind -- this sweet, happy, little jumping-around kid -- pouring into his veins just quantities of drugs. I can't conceive of anybody doing as many drugs as Nic did.

Shares