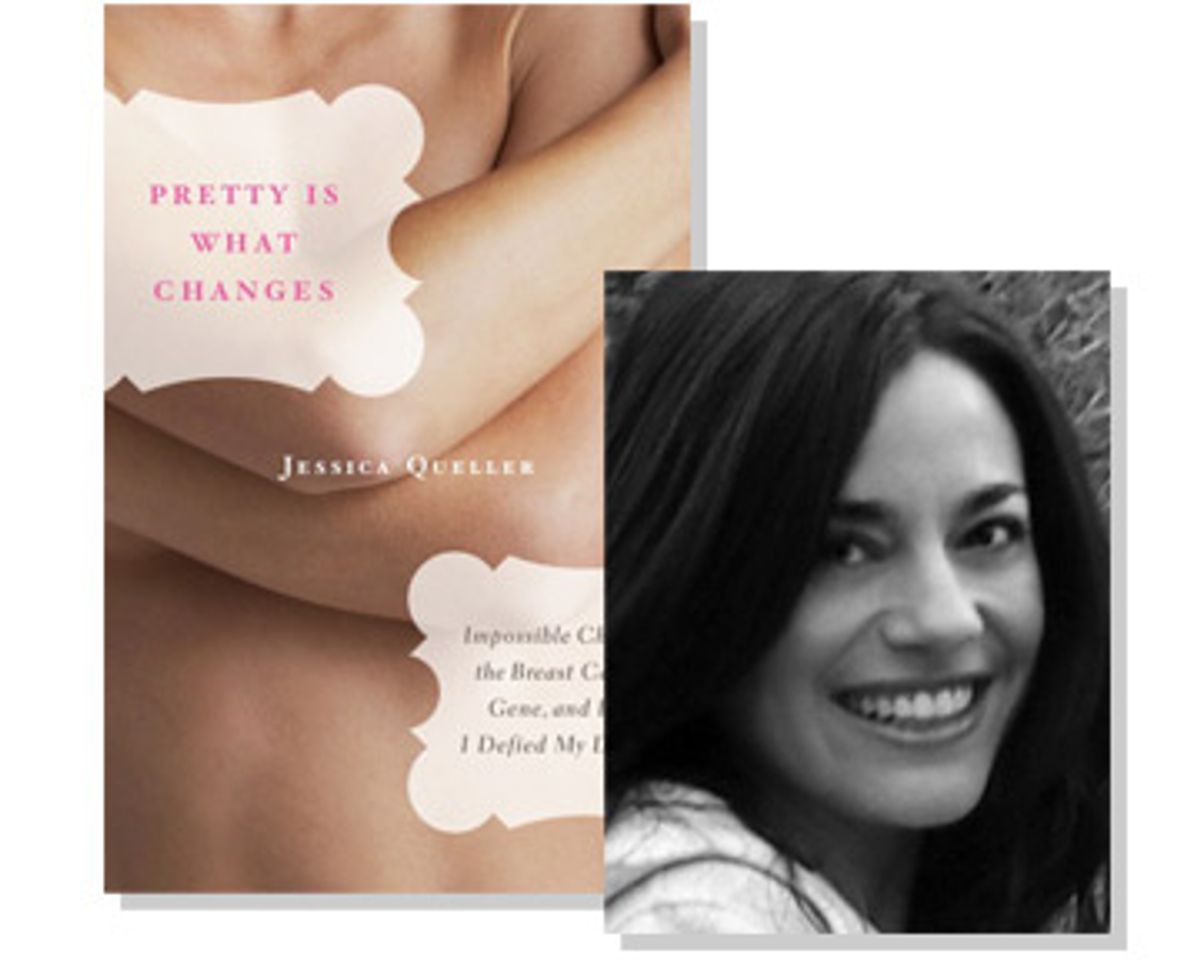

One morning in September 2004, while writing a rent check to her landlady and brainstorming ideas for a meeting, Jessica Queller made the call that would throw her life into a tailspin. Queller, a successful, 34-year-old television writer in excellent health, was about to discover she tested positive for the dreaded BRCA "breast cancer gene" mutation, which meant she had an 87 percent chance of developing breast cancer and a 47 percent chance of developing ovarian cancer -- the disease that had killed her mother almost exactly one year earlier. What's more, there was no way of predicting when the disease would strike; she could be 36 or 56. "It was as if I'd fallen down the rabbit hole and decks of cards were talking. As if the logic and rules of my universe had suddenly changed. And in fact, they had," Queller writes in her new memoir, "Pretty Is What Changes: Impossible Choices, the Breast Cancer Gene, and How I Defied My Destiny."

Queller eventually learns that women with the BRCA mutated gene face a no-win situation: They can submit to a life of constant medical surveillance (not to mention ever-present anxiety), or they can have radical preventative surgery -- having their breasts and ovaries removed.

"To cut my breasts off or not to cut my breasts off," she writes at one point. "That is the question." This unforgettable memoir, which evolved from a provocative 2005 editorial in the New York Times, takes us through Queller's agonizing decision to undergo a double mastectomy. (She plans to eventually have her ovaries removed as well.) In addition to explaining the medical research for laypeople, she turns her focus inward to examine notions of beauty, sexuality and identity, in a way that is not just personal and moving but also sharp and funny. Queller is a former actress who has worked as a writer and producer for shows like "Gilmore Girls," "Felicity," and currently, "Gossip Girl," and her humor and cinematic narrative skills give her story a lively snap.

Finally, Queller uses this book to pay homage to her glamorous fashion designer mother, whose slow death by cancer at 58 clearly still haunts her. "For me, this book is about my mom," Queller says. "My decision to choose surgery is nothing compared to what she went through, and what my sister and I had to watch."

Jessica Queller recently spoke with Salon by phone from her home in Los Angeles.

Can you explain how you came to take a test for the breast cancer gene?

When my mom was diagnosed with this advanced ovarian cancer, my best friend from high school, Gillian, said, "I'm on the board for a charity for women's cancers, and I think you're at high risk now. You should speak to my friend who runs this organization and get some information." I was not worried about myself at all at that point. I was 31 years old, and even though I knew my mom was dying, I felt completely invincible -- my own health was not on my mind.

I didn't think about it once for the next two years. Then, about eight months after my mom died, I was finally going back to L.A., getting a job and going back to normal. I was realizing that my driver's license had expired, my teeth hadn't been cleaned in three years, all these things. So I started to think about focusing on my own life, after three years of taking care of my mother. I said to myself, "I might as well just get that blood test and know for sure that I have a clean bill of health."

After you tested positive, what was your reaction when the counselor brought up the idea of prophylactic surgery like mastectomies and oophorectomy?

I was indignant. I thought she was supposed to be a therapist, helping me to feel better, and it was like she was scaring me with these outrageous proposals. How dare she make me feel like I was sick or could be sick soon! Looking back on it now, I realize I was just so in the clouds.

In the book, you express frustration that there was "no clear course of action" and that the doctors couldn't offer you any guidance. What was the guidance you were looking for?

When you find yourself in that kind of dire medical situation and you're feeling very vulnerable, you want the doctors to just tell you what to do. But it was surprising to me that none of the experts really felt they could give you a directive. There are pros and cons to each decision, and it's such a personal choice. As science advances, I think it's important for all people to grasp that they will have to be their own medical advocates in the future, and that doesn't mean you don't get guidance from doctors, but every person is responsible for educating themselves as much as possible and weighing the choices, because they're not clear-cut.

How did you come to the decision of getting the preventative double mastectomy?

This kind of thing really forces you to soul-search and tap into your own values. For me, the question was: Would I be happier to not to take the test at all, not have the knowledge, and whatever happens happens? A lot of people feel that way. Or would I be happier knowing everything, even if I don't like the news? Then, later, the question became, would I be happier to keep my breasts and take my chances and if I get cancer I'll just deal with it then, or will I be happier to go through this awful surgery now and have peace of mind that I probably won't get cancer?

People often ask me, "Do you tell all women that they have to do this?" I don't believe in proselytizing about anything, and especially about this subject. Obviously I felt that the choices I made were right for me and my life, but this is so personal that everybody really has to decide for themselves what would make them most at peace.

When your mom was your age, this test didn't exist, so she never had to face this kind of decision. Were there moments when you envied that kind of blissful ignorance?

I had a few moments of that, but mostly I didn't feel that way. My personality is such that if there is news out there, I want to know it, even if it's bad news. I'm the type of person who wants to know if my boyfriend is cheating on me. I don't like people to know things that I don't know. I do wish the test wasn't true. I do wish I didn't have this gene. But if I had it, then not knowing wasn't going to make me feel any better.

Were there people who tried to convince you that the mastectomy was an unnecessary measure?

Absolutely. Many of my friends were shocked and horrified and thought I was being melodramatic. They thought this was just extreme, and wrong, that I was traumatized from my mom's death. People were very judgmental. Everyone from my friends to strangers online. So many people posted things online after this "Nightline" interview that I did, saying things like, "Please, Jessica, don't do it, you could get hit by a bus tomorrow, you never know. " One guy wrote, "I can't believe she's doing this. It's the equivalent of being castrated."

Why do you think people had that kind of reaction?

This concept touches a nerve. People are imagining themselves in this situation and trying to decide what they would do, and they don't want to accept that [the preventative surgeries] might be a smart thing. The concept of mastectomy is still so scary. After hearing my story, strangers would actually say, there's no such thing as that test, that can't possibly exist. This is alien to a lot of people. And it does seem very science-fiction.

At the time you were writing for "Gilmore Girls." What was it like to write for a show about two women who are quite possibly the most idealistic mother-daughter pair ever, when you suddenly had to start worrying about your own chances of bearing a child?

Making up silly plotlines like, "Are Luke and Lorelai finally going to get together? Is Lorelai going to go back to Christopher?" -- it was not that emotional. My own life was so heavy that writing for TV was an escape.

Did you ever think about incorporating any of your own experiences into your work?

For stuff like "Gilmore Girls," it wasn't really appropriate. But my friend David was the head writer for "ER," and he actually wrote an episode for that show based on my story. He called to tell me they were doing the show just as I was going under the knife. I was in bed, in bandages, when I watched the "ER" episode. I had such a crazy emotional reaction. I'm usually the one in the writer's room stealing stories from all my friends' lives, and now I was the subject of this drama that I normally make up! It was very surreal. A few weeks later, "Grey's Anatomy" did a story almost identical to my story as well. I never got confirmation that it was based on me, but I've worked with some of those writers previously.

The prophylactic surgeries are still not 100 percent effective, are they?

The statistics I read online said it only decreased your chance of breast cancer by 90 percent, and that concerned me. But when I interviewed surgeons, I learned that if you go to a very aggressive surgeon who focuses on getting every cell, every scrap of breast tissue, the odds improve. The studies haven't come out yet, but it is believed that your chances of getting breast cancer can be reduced to 1 to 3 percent, whereas the average American woman has more like a 12 percent chance of getting breast cancer. That made me feel comfortable. I went to one plastic surgeon who told me I should go to a breast surgeon who leaves some tissue because I'd get a better aesthetic result. I was like, "Are you insane?! The point is to have a zero percent chance of getting cancer! I'm not going to leave in tissue so that my breasts look a little prettier!" You can never be 100 percent sure, but I feel really confident that the danger of my getting breast cancer now is minute.

The reconstructive surgeries sound much more advanced than I'd expected.

Thank God! I think the reason why I was terrified -- and a lot of women are still terrified -- about the concept of a mastectomy is because we think about our mothers' generation and our grandmothers' generation and what a mastectomy looked like back then. The concept and the stigma still linger, but plastic surgery is so advanced that you're really put back together again beautifully.

Your last reconstructive operation was two years ago. Are you still happy with your breasts?

I am happy. I had nipple reconstruction, because preserving your own gives you a higher risk of getting cancer. So they're not real -- it's skin grafting from my hips. But they look so real, it's uncanny. I do have visible scars, battle scars. But otherwise, it's totally fine. For a year, my breasts were numb, like with Novocaine. And then all of a sudden, I was like, oh my God! I have feeling in them again!

You know, I just have to say, it's really embarrassing for me to talk about anatomy and this kind of thing out loud. If I hadn't been through all of this, I'd be the last person who would ever be talking about my body.

Well, I thought it was wonderful how all the post-mastectomy women you talked to in the book were so open. The women who'd had reconstructive surgery seemed so eager to show you their new breasts!

It's very sweet. Everyone who has to go through this is so afraid that they're going to look deformed, and that their femininity will be ruined and their appeal will be gone. So when the results actually are quite pretty and appealing, you want to be like, "Look! Don't be scared! It's not that bad. It's even kind of nice."

As a single woman who has yet to have kids, have you found that you are in the minority among women who chose to undergo prophylactic surgeries?

When I was having my surgeries three years ago, I was. Back then, I couldn't find any threads on the FORCE [Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered] Web site about young single women. Now, there are dozens of them. It's definitely moved into the zeitgeist, especially in this past year. A woman in Chicago named Lindsay Avner started an organization called Bright Pink as a resource for young women dealing with this. Lindsay had prophylactic mastectomy at 23. She's been all over the media, and she's kind of become the spokeswoman for young women like us.

You're 38 now. Are you still planning on having your ovaries removed at age 40?

Yes. Ovarian cancer is rarely early onset, and risks increase tremendously after age 40. Ovarian cancer is especially deadly because there isn't a reliable screening method. By the time someone is diagnosed, it's often late-stage.

In the book, you talk about your desire to have children of your own. Are you seeing anyone now?

I am not. My last serious boyfriend and I broke up about a year ago, and I dated a little bit after that, but right now I'm really focused on fertility.

Have you pursued your intention to become artificially inseminated?

Yes. I've tried artificial insemination several times, and so far it hasn't worked out. With the stress of traveling and promoting the book, I've put it on hold. To be honest, I had been hoping to be pregnant by the time the book came out.

In the book, you mention a technique called preimplantation genetic diagnosis that would allow you to genetically test fertilized embryos for the BRCA mutation. Are you considering this procedure?

No. I don't think I could do it. To not select embryos that have the gene that I had and my sister had … the guilt would be too much to handle. If I have a daughter I will pray she is in the 50 percent that don't have the BRCA mutated gene. If she does, I'll hope that by the time she's 35, we'll have a cure for breast cancer. Now, I'm not pregnant yet, so I suppose I could change my mind. But at this point, I feel like that's a line I can't cross.

Shares