To listen to a podcast of the interview, click here.

To subscribe: Click here to add Conversations to iTunes or cut and paste the URL into your podcasting software:

Once upon a time, Sandra Tsing Loh was a poster child for the First Amendment -- "the Jennifer Aniston of amendments," she says -- popular, glamorous, easy to love. This was back in 2004, shortly after Justin Timberlake ripped off part of Janet Jackson's costume and revealed her bejeweled right breast to the Super Bowl-halftime-show-watching masses. Freedom of speech was very much on everyone's mind -- and when Loh got fired for inadvertently uttering the F-word on her Los Angeles public radio show, she found herself a cause célèbre.

"It was amazing. Suddenly I was the coolest thing," she says now, recalling the heartfelt letters and enraged editorials written on her behalf, the invitations to swanky events. "When you're finally in that little updraft, you're like, 'Oh, this is the high life -- fantastic!'"

But not long after her big media moment, Loh -- who has five books and one-woman shows to her credit, has been a regular commentator on NPR's "Morning Edition," PRI's "Marketplace" and Ira Glass' "This American Life," and now holds forth on everything from science to women's issues on her two Los Angeles radio shows and in the Atlantic Monthly, where she is a contributing editor -- found her real cause: rescuing our urban public schools. Yes, yes, she can hear you yawning. "This public education thing is so huge, yet … it's so unsexy," she says. "I would go to parties and people would back away. 'Oh, there's Sandra. She was fired last year for obscenity. Now she's into public school. Good luck with that.'"

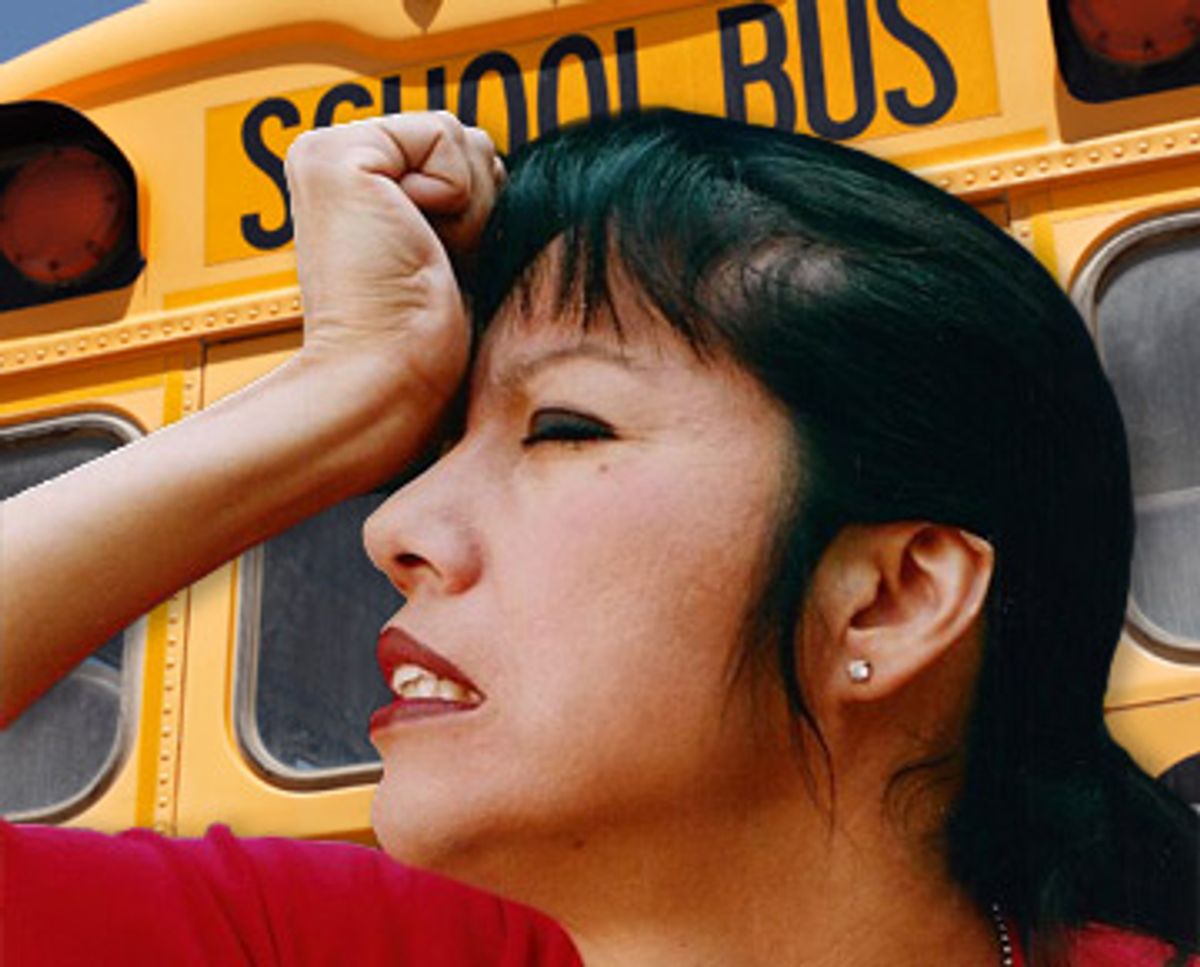

Those people haven't read Loh's hilarious new book, "Mother on Fire: A True Motherf%#$@ Story About Parenting." Or maybe they just don't live in a big city and have kids they can't afford to send to private school. Anyone who does will be riveted by Loh's lively, furiously paced, brutally frank account of her own search for a school for the elder of her two daughters -- or, as she dubs it, "the year I exploded into flames." They will also undoubtedly, and regretfully, recognize their own shameful insanity, their own unshakable obsessions, their own false starts and interludes in which they followed false prophets (private school admissions officers, mothers who think they have all the answers, therapists who live cloistered, tastefully appointed lives).

For any parent who has ever worried that her children will end up uneducated and deprived of art and music because she has chosen a career in the creative fields rather than, say, podiatric surgery, for any parent who has ever dissolved in tears after being ignored by the self-important secretary behind the desk at her corner public school, for any parent who has ever felt the searing pain of unrequited love after touring a fancy private school or suffered an existential crisis while considering a move to the suburbs, "Mother on Fire" will function as much-needed salve -- and inspiration. Because if public school is the urban middle class's tragic fate, it is also one that can end in a catharsis. And after we follow Loh on her journey -- through fluorescent-lit schools, complicated female friendships, the elaborate dances of decades-old marriages -- we emerge euphoric, flush with community spirit and able to laugh at our own insanity.

Still shaky from my own all-consuming quest to find a school for my 5-year-old son (he'll enter kindergarten in one of New York City's fine public schools in September), I spoke with Loh. I reached her at her bungalow home in Van Nuys, Calif., where she was no doubt surrounded by women's literature, PTA fliers and thousands of her daughters' tiny socks.

Why does the search for school make parents so crazy?

I think it's partly a generational thing. I'm 46. In our 20s, women in my generation, we all wanted to be Laurie Anderson. "Oh, she's playing violin on roller skates on an ice block in New York City and going directly from that to her Warner Bros. 'O Superman' tour." So we thought that's what you do: You stay true to your own artistic principles, you don't compromise anything, and then you end up with a giant record deal, all this money and a fashion spread in British Vogue. You go to college, don't get married, don't have kids, become Laurie Anderson, make all this money and sing your song. And then our 30s came along, and reality set in.

And now that we have had kids, parenting has become so consumerized. Even when your baby is in the womb, you have to eat a certain kind of kale and put the Mozart headphones over the belly and have the right kind of sleep pillow. And because communities have fallen out, where you don't have the grandmother or the aunt around to help you, you're just kind of alone in your fear bubble. Into that void come the lactation consultants and the new mommy groups that are all heavily marketed. The mommy Web sites, if you are unfortunate enough to read them, have the Bugaboo stroller ads -- all the "advice" is always laden with stuff that you're supposed to buy.

You're just in the habit of swiping the Visa and solving all your parental problems. So by the time you get into preschool, everybody is kind of fear-based and chattering. And even the 2-year-olds are trying to practice their block work to get into the best kindergarten. You're pretty much surrounded in this bubble by people who are going to swipe their Visas and get themselves out of the horrible public school system. Which I had never directly experienced.

It's a key theme in your book: how people fear public schools -- without knowing anything about the public schools.

When I was at public radio looking at kindergartens for [my older daughter] Madeline, for months I did not meet anybody who had their kids in public school in Los Angeles, which is really shocking. I'm a journalist so my friends are journalists: magazines, newspapers, even public radio. Nobody had their kids in public school. That's why I would never think of just going to the corner school and poking my head in. Because that's like going to the DMV.

My generation is so used to having our public spaces look like the Starbucks, with the beautiful lighting and the little bit of Nina Simone and my coffee that's blended a certain way from Costa Rica. So the first time you walk into a public school, you go, "Oh my God the lighting is really ugly. Why are those flags drooping so sadly there? Why does the person typing not look up?" It's a real shock to the system.

And yet when you looked inside it, you found some surprising things.

I did. There's so much catastrophizing about public school by people who have not set foot in there for decades because "no one goes there." I really don't think our school system is an evil borg force. It's sort of like the government. It's not even efficient enough to be a borg of total evil, even if it wanted to be.

So yeah, you find many things. It's like Costco, as opposed to a specialty store like Dean & DeLuca. The Dean & DeLuca is very inviting, it's personal, it's got the beautiful lighting and everything is where you'd expect to find it, but you're spending an arm and a leg. Costco has hellacious lighting and the parking is terrible and you've got these huge towers of paper towels. But if you comb through those aisles, you see hothouse tomatoes on sale and Glenlivet for, what, $10? I remember one time seeing Yo Yo Ma actually play at our local Costco! You'll find some amazing value in there if you just get over the lighting and look. And as a middle-class person -- because there's a huge divide that's fallen out between the upper class and lower class [in our cities] -- we just have no choice. The good school district is $1.5 million homes. Private schools when I was looking were starting at $14,000 and now they're definitely in the 21s. Especially for two kids, it's really unaffordable.

So part of it is that we're accustomed to paying our way out of parenting trouble spots, but is choosing a school for our kids also about our own identities as parents?

I think identity is definitely a part of it. And it may be something that we women are going through at this peculiar time in our lives. I know a fair number of women who have opted out in that Lisa Belkin way [Belkin's 2003 Times magazine cover story told the story of Ivy League-educated women leaving the workplace to stay home with their children]. They just simply -- no matter what feminist argument you try to throw at them -- really are happy to be out of the grind of the workforce. But then they're looking around and thinking, well, what do I do next?

There's the competition of getting into these schools, which in a way replicates what one may have had in the workforce -- but in a way that you go, I can win this game, though, because it's just kids. I had, at the beginning, a false confidence that I could game this system. People would go, "Oh, call this number of this person on this card, they'd love to have you guys at their school. You're at public radio, that's so cool!" So there was a moment of flattery -- before I realized that public radio is like being the genteel poor in L.A. It doesn't actually count for that much. I thought it would, and it didn't. Only Ira Glass' name counts.

Even if you can't afford it, the private schools can be awfully alluring.

That's what's so fascinating about them. I often thought, you know, if I wanted to make some money, I could start a private school. I could start it out of my own house in Van Nuys and call it "The Cottage" or "The Bungalow." And you know we've got mulberry trees around here, and they're dying, but we could call it "The Mulberry Cottage." And we could start a newsletter. I became fascinated studying the newsletters of all the private schools.

There was one nearby here where the newsletter was all written by the parents, which is, when you think of it, a little infantilizing. There were men and women writing about how, that day, the first graders had looked at rain coming down on petals. And one parent was writing about his own memories of rain coming down on petals. So the newsletter was an ad hoc literary magazine for the bored parents to think about their own childhoods. In a way these private schools allowed a certain class of parent a way of being that they didn't find anywhere else in society. And especially in L.A., where people find themselves cut off and it's really very hard to find your tribe. Sometimes a private school will give you a sense of tribe that you don't find anywhere else in the city.

That's interesting, because we've lost a sense of community by not sending our kids to public school, too. When we were kids our parents just marched down to whatever public school was handy and enrolled us, and that was our community, because those were our neighbors.

Oh, absolutely.

But now there's all this fear, all this isolation. How did we get here?

You know, the magnet system is so complicated in L.A. We would throw these soirees called "Martinis and Magnets" to explain the system and then ply the crowd with martinis just to ease the pain.

I started doing these questionnaires. I'd say, "OK, before we get started: On a scale of 1-10, how terrified are you of your local kindergarten?" 11! "Have you ever set foot inside that kindergarten?" No! "Do you know any living soul who has ever set foot inside that school?" No! "How do you know the school is so bad?" Uh, neighbor ...? Nobody had any direct experience of that school, but they were so terrified.

And the other thing we would do on this questionnaire. I'd say, "What was your peak educational moment?"

One woman wrote, "None! The day I left grad school was my peak educational moment, and I want to spare my 4-year-old the same experience." And you'd go, well, that's not very promising.

And another person wrote, "My peak educational moment was in graduate school in modern dance choreography, the day we turned our chairs in toward each other in a circle and were able to finally share freely." And then you're going, OK, so you're trying to re-create in kindergarten what you had at the graduate modern dance choreography level. This just is not possible, it's not realistic, and it actually may not even be very good for your 4-year-old who probably just needs to learn to hold a pencil and sit in a room without twiddling.

On the other hand, public education has to come into the 21st century. They have to say, "Good morning, may I help you?" at the front desk. And maybe in big public school systems there haven't been enough highly demanding, aggressive parents to say, this is insane. We are going to sue you unless you say "Hello." I think the two poles can come a little closer together.

Well, I've had that experience at the front desk at some schools. And then I've found, as you did when you dove a little further into the system, these pockets of amazing people working in the school system -- who really care and want to make a difference. It's your Costco theory: You look a little further, and you find the gourmet tomatoes. So how do you get people to look? And have you noticed a change since you first became an evangelist for public education?

Yes. When I began, in 2004, nice, liberal, Democrat, NPR-listening people [in Los Angeles] did not even discuss public school. They just slid you the card of some private school under the table. Now the conversation is very much on the table. It feels like there is a bulge in families whose kids are going into public school now. It's the tipping point of the real estate prices being so ridiculous. And we were one of those families that, had we been able to buy our way out of the problem, I would have been the first one off the train. Because I thought, it's undoable. I can't fix it. But we just could not move from our house and buy a $900,000 house. And we couldn't afford the $30,000 a year for my kids to go to private school either.

That's when I thought, how bad is that corner kindergarten anyway? If they even take them off my hands for three hours, that's free childcare right there, and then I'll drill them on the alphabet. It really cannot be worth this much money. And then I visited, and I realized, well, they do have an alphabet and they do have a playground and they teach them numbers -- this is not bad. And I started putting back my expectations.

Many of us turn to public schools because we really don't have a choice.

Everyone has been outpriced. Because the generation before us, those dreaded baby boomers, they swiped the Visa and left nothing behind. It was like strip mining. They took what they could and left nothing for the rest. Not that I blame the boomers, but why not? Let's blame them! They stopped the war, then they worked at corporations, and they were done -- and they still think they've saved the world. But in terms of public education, many of them left a blasted landscape behind.

So you think this is really our generation's fight?

I think so. When busing occurred in the '70s, it was not in a very sophisticated way. So in L.A., you had white Jewish Valley children being bused to South Central. I'm all for cultural blending, but I think it has to be done in a smart and thoughtful way. And it was not done that way. So that was the first big exodus -- in the '70s. Now you have these children in their 40s going, you know, it may be time to do this legacy a different way. I think it is.

It's also a shift in terms of conversation. I think for good liberal Democrats of my ilk, for people to sit around and say, "Public education, no one can go there" -- I don't think that's a fight that should be allowed to be abandoned in conversation anymore. It's a bit like if you said, "Yeah, I toss my recycling right into the landfill. I don't even bother to separate my recyclables. What's the point? We're all going to hell, anyway." That wouldn't pass in nice company. I think we need to start changing the conversation so it's not just a given that we're going to send our kids to private school and that that's better.

Part of the appeal with private school is that it's full service: Once you write the check, you don't have to do a thing. That's a big difference between what we public school parents face. We need to get in there and actively make things happen. For instance, you started a music program at your public school.

At our school, they're learning to read like gangbusters, the teachers are great, the solids are definitely there. But they didn't have instrumental music. So I found out that VH1 gives grants of new musical instruments to schools, and I did a lot of fancy footwork to get these instruments to our school. Sometimes with these school grants, it's like the Mafia truck drives up and stereos fall off. And it's like, get the stereos! I don't know where we'll put them, but get them! It was like that with these instruments. We got them, and then I had to find a music teacher and then pay the music teacher. It was a bit of a thing to unravel. Yet for me it was sort of fun.

We needed an after-school program. We didn't have one. And our PTA, we were able to start an after-school program with arts and crafts -- and even piano. Piano lessons, they're $55 for half an hour to teach a 6-year-old. We can't afford that either. And if we don't have affordable piano lessons, no one will play the piano. So we got these affordable lessons. I'm in a pocket of bohemian parents who have a little extra time and can teach an art or craft class. Five dollars a lesson, maybe $6, pretty cheap. We scholarship people for free and we still have money left to pay our violin teacher. It's an economy of scale. We know how to rub quarters together and make something.

It sounds like you're advocating volunteerism as a way out of our parental fear bubbles.

Yes, and I think many times people who are in those bubbles feel so much more trapped and alarmed about their children. In my book, I drew a lifeboat, where, at the very tip of the lifeboat, are the top 1 percent of the earners. They're both dual lawyers. Their children are set financially. But they're the people that are most anxious that Dylan doesn't have a native French speaker in second grade. The whole thing will collapse! They're looking over the tip of the lifeboat and seeing the sharks circling, rather than looking behind them and seeing how much luckier they are than the rest of the country. When you look at immigrant children, four out of five English-learning immigrant children will not even have one native English-speaking friend. And white children are actually the most segregated of all tribes in America right now because they're so kept from the other children. And that's really alarming for these immigrant children who are not even going to be around native English speakers so they can have a better chance of those higher ways of learning the language. Our children are going to be totally fine.

It's like we've forgotten how to think communally.

Right, even with play dates. When you first have a child, you realize either I can hire a baby sitter for every single hour that my kids need to be watched, or if I can make a mommy friend, they can go over there for two hours while I work and then they can come over here for two hours and then she can work. Just on a basic level, you start seeing that there are financial advantages to forming little tribes and groups, that you can save a lot of money.

And I think that goes back to the public school thing, where on one affluent block, in Los Angeles, every morning about 7 a.m. you see the four Lexuses and Range Rovers bolting out of the driveways and going to four different private schools in four different remote parts of the city. If they each just went to the corner public school and took one year of tuition -- $25,000 a year -- and put it into that school for one year, that would be $100,000. That school could buy a new gym, and everyone would save so much money -- you'd save gas, you'd save the planet -- if people just looked around and started thinking a little more communally rather than competitively. And we may have to do that in these apocalyptic times.

I feel good about the apocalypse. Because I think people will have to relearn their habits, and I think it's going to be better.

Shares