Several years ago, Jessica Helfand wandered into the scrapbooking area of a crafts store and stumbled upon a multibillion-dollar industry. An alternative universe of visual accessories greeted her: flair and foil, lace wraps and eyelets, glitter and "word fetti." An eloquent design critic and graphic designer who teaches at Yale, Helfand was flummoxed by this close encounter with the scrapbooking community and decided to write about her ambivalence for Design Observer, the Web site she co-founded.

"It's at once horrifying and fascinating to witness the degree to which design is being discussed online by people whose concept of innovation is measured by novel ways to tie bows," Helfand confessed. Unable to resist a further jab, she continued: "I could write an entire post just on the scrapbooker's predisposition toward fonts like 'Whimsy Joggle' and 'Pool Noodle Outline' but I will try and restrain myself."

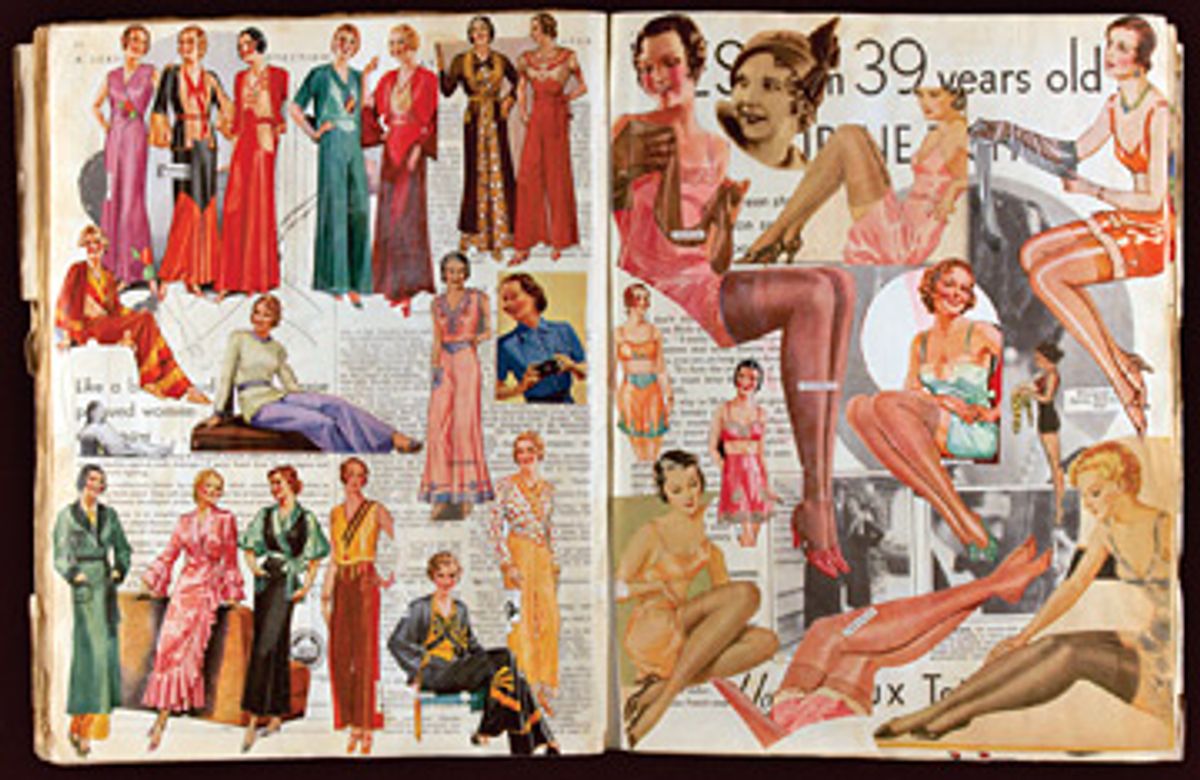

Helfand couldn't dismiss scrapbooks altogether, however. Although they were often cheesy and sentimental and generic, this was also hands-on design as practiced by regular people rather than artists -- an attempt to represent everyday experience through visual culture. Digging through archives, she was amazed by the medium's rich pedigree. The result of all this research is her captivating new book, "Scrapbooks: An American History," which explores American life over the last two centuries through the prism of the humble scrapbook.

This beautifully illustrated coffee table tome suggests that the scrapbook is an amazingly flexible medium, one that adapts to and reflects the times. In fact, it may once even have been ahead of its time. Helfand calls it "the original open-source technology, a unique form of self-expression that celebrated visual sampling, culture mixing, and the appropriation and redistribution of existing media." That may sound a little too highbrow for an artform that thrives on ribbons and roses, but Helfand's text points out that all kinds of lively minds have kept scrapbooks over the years, from playwright Lillian Hellman (who hilariously kept track of her running feuds and pasted in nasty clippings about herself) to poet Carl Van Vechten (who maintained a clandestine and artful compendium of male pornography) to Anne Sexton, who gathered telegrams, recipes and fledgling poems into a newlywed's memory book, 25 years before she commited suicide. Mark Twain not only recognized the importance of the format but also profited from it, patenting the first "self-pasting scrapbook" back in 1872.

But "Scrapbooks" doesn't dwell on famous names. Helfand is more interested in peeking at the historical shifts embedded in the way people recounted their lives: the episodes they chose to describe, the objects they included (newspaper clippings, gum wrappers, dance cards, dog tags, family photos), and even the way they laid out the pages (sophisticated modernist visual styles like collage had somehow already been absorbed by ordinary scrapbookers of the early and mid-20th century). She zooms in on an antibellum society woman whose marriage is (shockingly, for the times) falling apart, the privacy of the scrapbook's pages liberating her to record her life as she wanted it to be. Then there is the Seattle doctor, an immigrant who crams his meticulously laid-out book with portraits of presidents and newspaper clippings on wartime health -- "a kind of self-initiated primer for good citizenship," as Helfand notes.

These books are remarkable to look at -- so individual and specific, each becomes a "repository of evidence" from someone's life. An early 20th century young woman's scrapbook veers between movie star worship and suffrage marches, whereas a WWII soldier's volume gathers together enlistment papers, medals and Japanese money. In fact, war and danger seem to spur the desire to preserve memories and make one's mark, and Helfand partly traces the current mega-boom in scrapbooking -- now a nearly $3 billion industry with its own national holiday and a vast network of Web sites, groups and retreats -- to the trauma of 9/11.

Helfand spoke to Salon by phone from her design studio in New Haven, Conn., about the beauty of homemade things, religious scrapbooking and the future of memory in a digital era.

The piece you originally wrote about scrapbooking in Design Observer got people very angry. The scrapbookers felt insulted, but the serious design people were pissed off, too, because you didn't completely dismiss this practice. Why did people get so agitated about such a humble hobby?

The design people called the scrapbookers "crapbookers," and the scrapbook people thought I was being a Yale elitist professor. There was one woman who said, "I'm a thoracic ER nurse, my husband is on disability and I have three kids and no money -- this is the only pleasure in my life. How dare you criticize me?" And I thought, yes, how dare I?

Writing this book was very hard, because I couldn't soft-pedal my willingness to accept this as graphic design under the standards I believe are important. But I do recognize the instinct to want to put pen or paste to paper and commemorate some aspect of your life. It's just when you see this $2.6 billion industry and people critiquing each other's work as "cute" -- it makes me break out in hives. But we're talking about raising money for a documentary about this because, in a kind of Morgan Spurlock, "Supersize Me" view of an American phenomenon, it is a world unto itself. Why are women targeted in this treat-them-like-13-year-olds way? I went to one of these scrapbooking retreats, and it's all these women in their pajamas with snacks -- Hostess Twinkies everywhere! There's something about junk food being part of this. It's like, no husbands, I'm going to let myself go and look at pictures of my family and eat Twinkies. It's not really about design, so it's out of my league in terms of a critique, but it fascinates me sociologolically.

There's a huge boom in DIY crafting, with everyone from indie-rock kids to stay-at-home moms selling their wares on Etsy and at regional craft fairs. Does crafting and scrapbooking come from the same impulse?

I don't know. What I found was that in the past, it wasn't always a gendered activity. I have marvelous scrapbooks in my collection by two or three men that are as beautiful and as detailed and as soul-searching as ones by women. In this most recent boom, which to my way of thinking is since 9/11, it's been very much targeted to women. A number of sociologists have done studies about what this is about. One of them was called "Making Me Time," about the creative crisis of the stay-at-home mom who needs to feel she's doing something with her day. The physicality of putting pen to paper and grease pencil to word fetti is making them feel they're doing something.

You object to the way today's scrapbooks are so schematic, right? There are rules and guidelines for how to do them, and every element of them is premade rather than just gathering the flotsam and jetsam of your life and organizing it in a beautiful way.

By and large, what is so beautiful about scrapbooks [historically] is that they are so messed up! They are messy. They are not chronological, and they go back and forth and change things, and they rip out pictures of guys they broke up with. They're so idiosyncratic.

I found this scrapbook of a woman from about 1912 who was clearly notoriously late to everything. Every note says, Please be on time to my party. Please come at 8:30. And in the middle of the scrapbook is a little gold watch and card that says, "Kitty is always late, it seems to be her fate, so here's a little watch, to help her keep her date." This woman was like my grandmother's generation.

There's something so humanizing and humbling about realizing, it's not now and then. It's us. It's part of some greater human need to mark what you were doing.

In the book you point out that there was a huge range of preprinted scrapbooks designed for soldiers or newlyweds or new mothers. My own mom kept a baby book about me that is crammed with so much data and detail that it's almost illegible. There are all kind of titles and headings that came with the book telling her what kind of information she should be noting down about her infant. Was that kind of instruction very common by mid-20th century?

Yes, and the enabling is very interesting. In these memory books I found from the late '30s and early '40s called "The Log of Life," there's a place for you to put your fingerprints, and it actually says, if you ever lose your memory take this to the nearest police precinct and they'll tell you who you are. This was right after the war, and I guess people were worried you'd have too much shrapnel in your brain and you'd need help getting home.

You think these are just silly scrapbooks, but then you start to see how they codify our expectations and our fears, and it's quite moving.

I thought it was interesting that the increasing popularity of psychoanalysis in the 20th century brought ideas of self-interrogation being therapeutic to the fore -- but was that bad for scrapbooks? It seems like people need these books less, now that there are other opportunities for expression.

So many scrapbooks these days seem to be about other people, like -- I'm going to make this about my son or my dog or the prom. But 100 years ago, a scrapbook was about you, about your experiences. And that's why I became so absorbed by them as biographical receptacles of people's lives. That's why the banal things could be the most important thing. My critique of current scrapbooking materials is that it creates a meaningless visual grammar. Why would you want to follow a pattern? It's like you take a giant piece of tape and stick it up to the wind and see what catches -- that's the residue of your day. I see a million things lying around my house that are going to say more about the life I live than going to the art supply store and buying something new.

I have a theory that contemporary scrapbooking is a little bit of a reflection of reality TV. You look at a show like "The Biggest Loser," or take Joe the Plumber -- he's famous for 15 minutes and now he's gunning for a singing career. People want to gussy themselves up.

They're ready for their close-ups.

Yes! So you take this scrapbooker, and she's thinking, I'm overweight and I don't want a picture of myself in the scrapbook, but I do want to show off my cute kids and pretty pink ribbons. It's this externalizing idea of, I want this to look good for everyone else so if I ever get famous my scrapbooks will show that I'm perfect. But the whole purpose was to celebrate the everyday.

The problem is that there is so much stuff in our everyday lives. It's hard to distinguish what's important or special. You have a zillion receipts. Which do you choose? What is special?

And you'll always have more. Whereas if you go to the art supply store and you buy Martha Stewart's pretty paste-on initials it's going to cost you $3.95 for six of them, and you have to use them judiciously. So then you have the fear, what if I put it in wrong? As opposed to just grabbing an old pencil.

Some of the examples of stuff people saved in your book are just gorgeous -- and weird. There are the tickets and flowers and calling cards, but my favorite is the girl you mention who pasted in her blisters. As if she needed to commemorate her suffering feet for all time.

Can you imagine someone doing that today? Unless Martha Stewart comes out with a "Beautifying your blister" collection!

I was fascinated by the way people I know, normally unsentimental people, were saving Obama campaign objects after he won, and even putting together scrapbooks of election material. Why do you think that was?

It's the most emotional thing that has happened in a public way since 9/11. And 9/11 was another time people grabbed everything and saved it.

Tell me about "faithbooking." I had never heard the term until recently, but I guess there's a huge number of faith-based scrapbookers?

If you are a Mormon you are required by the church to document your family history. The scrapbooking community is really huge in Utah. But people that are religious of any faith -- I was educated in Quaker schools, and I could see Quakers liking this because it's kind of a daily meditation. It doesn't necessarily have to be about Jesus and the church, but it can be about ethics and morals.

But what is interesting, in conjunction with faithbooking, is the notion of "journaling." Serious hardcore scrapbookers talk about anything handwritten as journaling. But any sentiment you'd want to express probably already exists on a sticker so you don't have to say it, because a lot of people don't trust their own handwriting, they can't spell, and they equate writing even in a scrapbook as something that has to be professional. So you buy these sound-bite cards and daily affirmations that have a Stuart Smalley quality to them.

In the book you write very excitedly about tracing the way people absorbed the visual grammar around them through old scrapbooks. Someone with no interest in avant garde art might reflect very modern ideas in the way they laid out a page.

That was so fascinating to me. I found a scrapbook of a woman in the 1920s who had decapitated the heads of everyone in her family and stuck them in a birdcage -- at a time when Dada was happening. A light bulb went off, and I thought, could you actually show that people had gleaned things from their environment that might change the way they visualize things in their scrapbook? And you find a girl in Iowa or a boy in Santa Fe who has done this even though they were nowhere near the salons of Paris -- so where did they see this? There were no movies and so little access to pop culture. But in the tilting of a word, or the collaging of something on top of something else, you can see modernism coming to America in these scrapbooks.

How much of scrapbooking is about preserving memory, and how much is about self-presentation?

On the topic of memory, they are using scrapbooking with Alzheimer's patients and victims of abuse now. They even use them with children who are moving -- real estate companies create scrapbook kits for kids so they can have some daily activity with the memories they're going to build in their new home.

What is happening to the scrapbook in the digital era, when nobody writes letters or prints out photos anymore? There is a whole community of digital scrapbookers, of course, but is the print version of the memory book going to vanish?

I was lecturing Yale undergrads, and some 19-year-old said, isn't Facebook a scrapbook? I'm sure there's some artist out there saving every single status update, but the digital is ephemeral and you have to actively pursue the fleeting digital evidence of our existence.

Right, you can't just put it in a box. You have to make an effort to archive it.

But those people who are choosing to print out their photos and make scrapbooks may have the last laugh because the materials they are working with now are much more [durable] than they were before. Archivists are struggling to maintain old scrapbooks, but in 100 years these things will last, they are indestructible. There will be an entire world of material culture studies that looks at just this, these scrapbooks.

Shares