It is no doubt surprising to Anne Lamott fans -- it is no doubt surprising to Lamott herself -- that the salty, emotionally honest writer who burst into the memoir world as the 35-year-old single mother of "Operating Instructions" is now a grandmother. Yes, that's right, Anne Lamott's 20-year-old son, Sam -- the baby whose first year she so poignantly captured in that book and, later, in many essays on Salon -- has started his own family. It's a reminder of what Lamott has wisely told us all along: that life does not unfold as you expect it to.

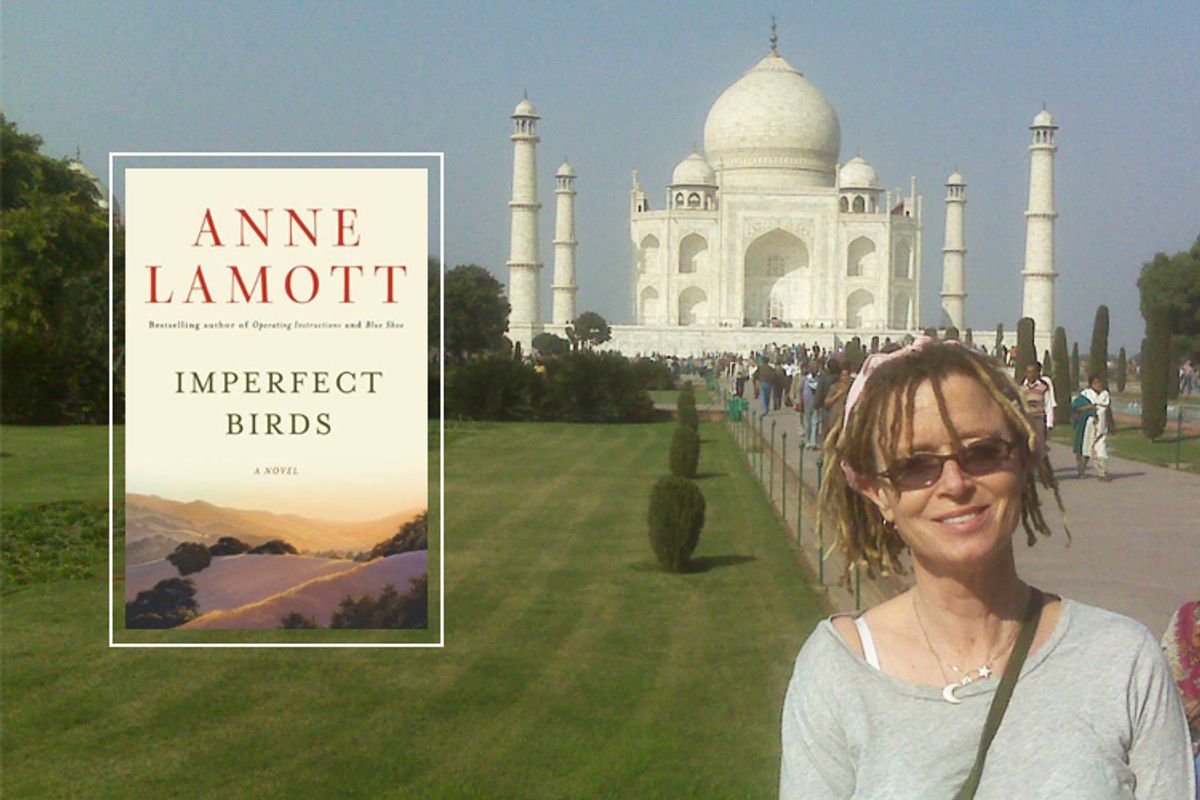

It's also a reminder of just how long Anne Lamott has been rabble-rousing and inspiring the masses, with a string of best-selling books about spirituality ("Grace (Eventually)," "Traveling Mercies," "Plan B"), one must-read manual on writing ("Bird by Bird"), and a cache of compassionate novels about people facing domestic crises, like her latest, the elegant "Imperfect Birds," the third in a mother-daughter trilogy that began with 1983's "Rosie" and continued with 1997's "Crooked Little Heart."

Set in the cozy, seemingly safe confines of Marin County, Calif., the book picks up as vivacious, straight-A student Rosie is drifting from casual drug use into red-alert territory, weekends lost to Ketamine and LSD and unprotected sex. Rosie's parents, Elizabeth and stepfather James, are caring but clueless. They argue, and fret, and gamefully ignore, but eventually they must stare down that ancient parenting dilemma: How to give your children the freedom to screw up while making sure they don't screw up too badly?

The guilt and stumbles of the well-intentioned parent -- and the self-destructive, carelessly manipulative behavior of the gifted, troubled teen -- become rich material in Lamott's skilled hands. As she told me about her subject matter: "Teenagers are so smart and alive, vulnerable, so at-risk, so brave and terrifying. They can be so mean, and so tender. So profoundly loyal to their friends and even to their moms. They can blow your mind with their brilliance and insights and passion. And they can be so stupid."

As she prepared for a book tour, Lamott and I e-mailed about those thorny teens, why she doesn't read mommy blogs and snooping on Facebook.

Can you talk about the meaning of the title? What does it mean to be an "imperfect bird"?

It's from the poem by Rumi, that each of us must enter the nest made by the other imperfect bird. If we want to have human connection, we have to enter other people's ragtag lives -- which is, of course, a nightmare, but which also makes us grow and stretch, and get out of ourselves, which is literally heaven. All we have to offer each other is the welcome into our own crummy nests, which are always half-coming-apart. And it doesn't seem like it could possibly be enough. But it always is.

And, of course, you wrote "Bird by Bird." Why birds?

I said in "Grace (Eventually)" that if birds were the only evidence that there is another side, or a deeper, bigger reality, birds and bird song would be enough proof for me. We are so bound, and they are so free -- and yet so vulnerable. The little ones you might crush, and the big ones might peck your eyes out or dive-bomb you. They're such alien creatures, so exquisite and yet springing from dinosaurs. And you can never look a bird in the eye -- their eyes are on either side of their heads, and they're so quizzical. They have to be -- they are prey, and yet so hungry. Just like teenagers. Just like us.

This book is about Elizabeth, a mother who is a recovering alcoholic, and her daughter, Rosie, a bright student who is getting deeper into drugs. There is also Elizabeth's second husband, James, who makes a living writing observant essays based on his own life. Since you have been all of these things, let me ask the banal question: How much of these characters is based on you?

Elizabeth and I share the alcoholism, but she has lifelong depression, and I don't. I am just a little bit tenser than the average bear. Unlike her, I totally forgot to get married -- but certainly meant to, and may well still get around to that. Elizabeth, Rosie and James are all totally self-absorbed, which, of course, I am, too -- as Salon's letter writers like to point out. I grapple with having equal proportions of narcissism and low self-esteem, which is like James (and almost all writers). Rosie's like me in terms of being smart, a lifelong reader, funny, way too sensitive for this planet, desperate to please everyone, like a little flight attendant -- until she starts drinking and stops caring. So my interior landscapes are similar to the characters. But virtually none of the things that happened in "Imperfect Birds," or the first two novels of the trilogy, actually happened to me.

To Salon audiences, you're primarily known as a personal essay writer. Do you sometimes worry that, as a fiction writer, audiences know too much about your real life? That we're preoccupied with it?

Audiences only know the stuff I've chosen to share with them. The only reason I go public with almost anything I write of a personal nature is because it has literally no charge left for me. By the time I write about it, I've told that story or done riffs on that subject dozens of times. I only tell on myself because I know it is universal, but people have not necessarily been able to say it out loud.

People think I spilled the beans about my son Sam's personal life, but between the ages of 16 and 19, when things were, let's say, occasionally hard-going, I told exactly one story about it, which I first published in Salon. (It was the one about my slapping him.) Now, I got a couple of hundred letters in response, and they were frequently pathological, but when Sam was 18, I gave a reading and lecture at a local university, and Sam invited 20 of his friends. I asked him what he'd like to hear me read. He chose that one story, saying it would help many parents who were going through rough patches, and -- this is a quote -- he thought it was the best thing I'd ever written.

Let's talk about a key tension in the book, which is the dilemma between being an overprotective parent who might push a kid away and a too-permissive parent who might ignore a kid in danger.

My experience as a parent and as the friend of other parents is that a lot of us grew up in alcoholic families, or where someone was mentally ill, or having affairs, which set the children up to be both extremely vigilant and in an unspoken promise not to see what is going on. These are the two main survival techniques, along with overachievement and perfectionism. So you grow up with these tendencies, and of course, having a child, especially a teenager, is like pouring Miracle-Gro on your character defects. So it's hard to find the balance between deciding to start seeing what is really going on, drawing some lines in the sand that your kid is not allowed to cross (like drinking and driving), and giving your kid the freedom to have a life and make mistakes and learn from them.

What helped most when Sam was going through his teens?

Having a couple of parents with whom I could talk about anything, and vice versa. People who could help me keep or regain my sense of humor, who just got it, when I was afraid or pissed off or clueless.

It also helped to have a healthy dose of fear. The stakes are very high. I can't tell you how many friends and acquaintances of Sam's have died of overdoses (mostly Oxycontin), had nervous breakdowns in college, usually drug-related, have had permanent injuries in car accidents. Another 17-year-old Marin girl -- beautiful, headed to college -- died after a teenage gathering out on the Tennessee Valley trail two Sundays ago. I was out there hiking before church, and there were 100-plus people searching for her, with helicopters, dogs. Her friends told me they had all gotten very drunk the night before, and she had wandered off. Her body was found in the ocean near Muir Beach.

So what does a parent do? The parents in the book snoop on their kids. Are you a snooper?

Of course I snooped on Sam. All parents snoop. Now I have no one to snoop on, except for the two dogs, which is very distressing. I've tried to use Facebook to snoop on old boyfriends or literary rivals who don't know we're rivals, but you have to belong to Facebook and be a "friend" of the person to do reconnaissance. So that sucks. Because then people could snoop on me.

When Sam was 19, you found out that he was going to be a father. What was that like?

It was really scary. Sam called me two days before Thanksgiving of 2008. He and his girlfriend -- who was 20, the cradle-robber -- had been together about a year and a half.

I was sitting in the old easy chair in my office when he called, and my heart just sank. I was so afraid for them, because it was so hard for me [to have a child] at 35. It's so hard for every parent, even when they are in their 30s and in healthy long-term marriages. But here Sam was in his first year of college, and doing great, having really found his niche studying industrial design.

But all I said was, "Oh, Sam." I somehow intuitively knew that it was none of my business. He was a grown man, and anyhow, I love Amy. I thought, This is their life story, not mine -- their heroes' journey.

I'm sure I cried but not on the phone with Sam. I knew grace would see them through -- that grace would meet them exactly where they were, and not leave them where it found them.

People were always shocked to hear Sam was a father, because he's kind of frozen in time for readers who've been reading about him all these years. The first time they met Sam was in the pages of "Operating Instructions" -- where, on the cover, he's about 8 months and wearing a Mervyn's tiger suit. Now his little boy, Jax, is that age, wearing a Tigger suit from Babies R Us.

What's it like to be a grandmother?

One thing that is great about it is that you get to pour your love into this amazing little being, really finally get in touch with unconditional love -- and then the kid leaves at the end of the day. It's so cool. You never feel trapped or bitter, like you do when you're the parent. It's an ideal arrangement. Sam's a wonderful father, very gentle and hilarious and hands-on. I have to pinch myself sometimes because I love them all so much. Of course, I thought I'd be going through this in about 10 more years, but what are you going to do?

One of the places you can really see the influence of "Operating Instructions" is in the proliferation of mommy blogs. I wonder if you read any -- or if you think, if you were a young and single mom now, you would be blogging?

I don't think I would have ever blogged. I am not even sure how you find someone's blog. What I loved were all those years of doing shaped, crafted essays about my life and spiritual or political pursuits -- but those 1,200 or whatever words took a full week to get just right. They were the length and the topics I love to read. I always used to tell my writing students to write what they'd love to come upon -- and I love deeply honest, authentic writing about the things that really matter in our lives. I asked Sam the other day if people could make money on Twitter or blogging, and he said, not really. Plus, my friend Mary saw a T-shirt at the airport that said, "No one reads your blog."

What I think is great is everyone writing their truth, keeping a written video of their lives, their families' lives -- growing up, and seeking connection with others in this very jarring and disconnected world. But I don't think I'm a blogging type -- I'm-too much of a perfectionist. I keep trying to capture moments and passages just right, so other people might find a little light to see by in my work. And that takes forever.

How are you feeling about politics these days? Healthcare reform? Obama? Hillary?

I cried on the Sunday when healthcare reform passed. I couldn't focus for one minute in church, and so I came home, had a bowl of Cheetos and my ubiquitous bag of plain M&M's, watched every single minute of TV until the House voted, well after dinner. I cried because it felt a miracle, and it was so great to imagine Teddy Kennedy and my old leftie parents watching in heaven, raising their fists in the power salute, hoisting a few beverages. Thirty-two million more people. It would have been sweeter to me if the careers of Joe Leiberman and Bart Stupak had been destroyed in the process, but that is because I am an awful person.

And Hillary! I am her biggest fan. I think she's been an incredible secretary of state, and Obama was brilliant to appoint her. She is just about the best thing about his administration (except for healthcare reform).

Have you changed your mind at all about Sarah Palin? You are now, I might point out, both high-achieving mothers of young parents.

I loathe Sarah Palin. What an idiot. I loved writing about her right after her nomination, in Salon, to cheer people up, because a lot of Democrats were worried right at first.

I hope Palin is the GOP nominee in 2012. I think I am going to start sending her money every month from now until the election.

So you're headed on an extensive book tour. How do you prepare?

Well, the main thing is that I always have to buy new underwear, in case I am involved in a plane crash. I do not actually believe in flying, as a concept, so best to be wearing nice fresh underpants, in case you are not burned beyond recognition. I just bought a whole new batch. My old ones were actually disintegrating. But nice and roomy and soft, like underpants a dancing bear might wear. Or Boris Yeltsin, if he ever got into cross-dressing.

Shares