Maybe you've noticed: The mainstream isn't that mainstream anymore. This spring, hordes of tourists stopped by Manhattan's Museum of Modern Art to see performance specialists re-create artist Marina Abramovic's signature works, balancing nude on bicycle seats and lying for hours under the weight of a human skeleton. Lady Gaga, with her Madonna-on-acid videos, has laid waste to the pop charts, inspiring a wave of leather ball gowns and freakish eyewear. The avant-garde has taken over, and it all started with Laurie Anderson. The godmother of the New York art scene, Anderson and her pioneering performances loom large over contemporary artists and musicians. Before mash-up artists used their laptops to whip dance halls into a frenzy, Anderson had invented a "talking stick" to allow her to play MIDI samples onstage. Before Auto-Tune became a focal point in hip-hop battles, Anderson was using various software to manipulate her voice. Her work blends experimental composition with pop synthesizer beats, mixing the aesthetics of the gallery spaces in Chelsea with sounds from the underground jazz clubs of the Lower East Side.

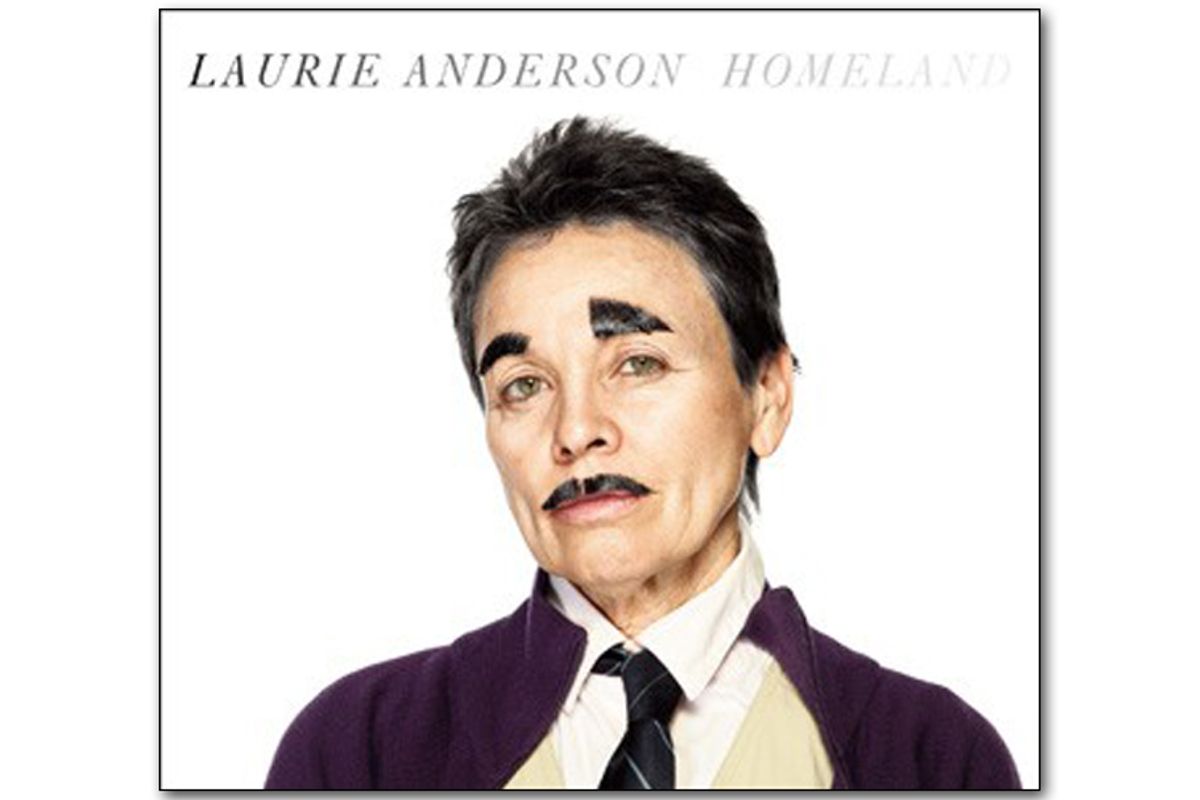

Nor has it ever been easy to predict Anderson's next move: During the big-haired, glam-rock, shoulder-padded 1980s, Anderson sported a sleek, androgynous look and set bizarrely lovely poetry to winding, eerie music. In the 1990s, she introduced a documentary on the history of the face before becoming a voice actor on "The Rugrats Movie." Her multimedia performances have been inspired by everything from "Moby-Dick" to NASA. This month, Anderson is releasing her first studio album in a decade, "Homeland," written on the road about America and co-produced by her husband, Lou Reed. Salon reached Anderson on the phone to talk about gender experiments, the humor in Lady Gaga's work, and why she hates the avant-garde.

You recently played a concert tuned so that only dogs could hear it. What was the inspiration for that?

The idea came to me about a year ago when I was backstage with Yo-Yo Ma. We were giving commencement speeches and sitting backstage and going, "Oh man, what are we going to say to these recent art school graduates?" I was just saying that my dream is to be playing some music and look up and see that the whole audience is dogs. And he said, "That's mine, too!" And we both said that if we ever get a chance we're going to do that. So when I was asked to curate the Vivid festival in Sydney, I asked if we could curate something for dogs and they said, "Yeah, why not?"

At first the piece was really within their hearing range. As it got closer to the date, I talked to a lot of doctors who said, "We do not recommend that, because you really don't know what will happen. You could be inciting a riot." So I dropped a lot of those pitches down. Frankly, we don't know what kind of music dogs like. I think people assume that they like classical, but there were a lot of rockers at this concert. As soon as we went on they were bouncing off the walls. We played songs to dance with your dogs and others were about finding the one spot that really gets to your dog as music does with people. There was a lot of contact between people and their dogs during the show. It was one of the sweetest concerts I've ever done, and it was on my 63rd birthday too, so it was a little bit dreamlike. I realized that if I'm an average person and sleeping an average amount of time, then I realized that on that birthday I had been asleep for 21 years. I thought, "Today is the day my dream self has become an adult. It can drink. It can drive." So it was kind of a celebration of that, too.

Your new album, "Homeland," comes out this month. You've been working on some of the songs in some cases for several years in your live set. How did they change since you started playing them?

When I started doing this, it was very loose improv, and some of them were called "Homeland." Instrumentals talking about Karl Marx and Herman Melville, nothing to do with each other. And gradually I put this together on the road. Eventually around 30 songs came out of it, and a lot of them are really political because it was at the tail end of the Bush years. I'm not a big flag-waver, but I do get some of my identity from my country. So when I started hearing about torture, it just made me lost and angry. And the word "homeland" for America has air quotes around it. No one ever says that word. Ever. No one asks, "How do you feel about your homeland?" That sounds like a bad translation from a small Balkan country. The Department of Homeland Security put an oversentimentalized word like "homeland" and sandwiched it between these really bureaucratic words. In the end, it's not about your homeland, it's not about security, it's about a certain kind of government control.

On your album, you perform in "audio drag" as Fenway Bergamot. How has that character evolved?

I've always done audio drag. I love it because it's a kind of weird puppetry. I use it not for itself, but to find another voice. You know, to say stuff and not just [drops voice a register] sound like this. It gives you a different take on things. Plus, I get so sick of hearing myself talk. Sometimes I'm in the middle of a sentence and just think, "Oh, no, I'm saying that again? It's just so pompous." It means that I don't have to be the woman, New Yorker, artist that I am.

Some of the gender experiments you worked with, like audio drag, are now the stuff of college curricula.

That's kind of ominous. They're teaching that stuff? Uh-oh. Those kind of phrases like "gender studies" or "performance art" kind of give me the creeps. For me, it's not about gender. It's about telling stories. It doesn't matter much that I'm a woman telling the story. I did a lot of school and I enjoyed it, but when I'm around there now I just think how glad I am that it's over. When anything gets institutionalized, the life goes out of it.

You spent a year as NASA's artist in residence. What are your feelings about the recent pullback on unmanned space flights?

I don't think we actually have to go there ourselves. It's risky, and we have some pretty sophisticated and beautiful machines for looking. They're not us. They aren't going to write songs or poems about it, but they can still be really inspiring. I think it's probably good not to be sending living creatures up on the tail end of huge explosions.

One of the elements of your work that I've always found compelling is the humor in it. Is that a conscious part of your shows?

Oh, yeah. I have secret ambitions to just be a comedian. That's what I'd really like to do, stand-up comedy. I don't think I've ever said that to anyone, but that's a really big part of what I do. I really trust laughter. It's really physical, and you can't fake it. I mean you can fake it [fake laughs], but then it becomes so creepy.

You worked with comedian Andy Kaufman in the 1970s. How did he influence your approach to comedy?

Oh, enormously. We used to go out to Coney Island to work on stuff. I was his straight man, and I used to tag along with him because I adored him. I was just a major fan. So we would go out to the "Test Your Strength" booth and we would stand around and just make fun of everyone who was doing it. I was supposed to beg him for a stuffed bear. And after a while, people would get sick of his taunting and say, "Well, why don't you try it?" And he tried it and hit, like, level one of 20. And then he would start complaining, "This is rigged. I want to see the manager!" It was really very funny.

You worked with Lou Reed on this new album. What's it like collaborating with your husband?

We don't usually work together, but on this record -- especially at the end -- I needed his help. Record budgets are not huge. I got to the end of my record budget when I was working on this and still had thousands of audio files to edit. Plus, I was doing it as a hobby for something like two days a month. And when you work on something for two days a month, it's hard to remember what you're doing. I was complaining about it a lot and Lou said, "OK, I'll come into the studio and work with you until you're done." And I sort of thought, "Is this a good idea to have your husband come in?" I would play something for him and he'd go,"This is done, move on." And I'd say, "Oh, no, that's not done. We have to redo the vocals." And he'd be like, "No, really, it's done." So that was a little different. But he's a great producer, and the record ended up having a lot of air in it. It wasn't just going from one digital box to another.

There's recently been a resurgent interest in performance art in the museum world, thanks to Marina Abramovic's work at MOMA. What do you think about the installation of performance art in a space like that?

Marina's a completely different kind of artist. I think a large part of the show is about documenting living things. It's a hard thing to do without getting a little bit theatrical or Madame Tussaud's kind of feel. I love Marina's work, but I felt uncomfortable seeing it re-created live because without the mentality, it's just not the point for me. On one level, I'm just not interested in it. But on the other hand, whenever I go see Marina's work I'm completely absorbed in it. I think that museums have a hard time representing certain kinds of work. One of the things I love about being a multimedia artist is how undefined it is. You don't have to be writing a book and have people ask "Why are you writing a book? You're a performance artist!" The thing is that I often start working on one medium, and it turns into a different one. I start working on an opera and it turns into a potato print. What I do is tell stories, and how do you fit that in a museum? They fit in your head, but they don't fit into the room.

But you must have some boundaries when you're working on something. How do you impose structure on your work?

If I'm trying to decide on a project, it has to have two of the three following things: It has to be fun, it has to be interesting, or it has to make money. The third one sounds crass, but when you're an artist, you do actually have to make a living. And you only have to have two of those things. It could just be fun and make money, i.e., doing work for "The Rugrats Movie." It's a really handy formula. Just to be interesting is, to me, what the avant-garde is about, and that's not enough for me.

That's interesting. Many people, myself included, consider you the leader of that avant-garde scene.

Oh my god, I'm just feeling myself more and more deadened by that kind of stuff. I don't mean to be a plebeian, but I think it's so repetitive. I go to some shows and think, "I went to the same concert about feedback in 1971 in a loft." It's the exact same thing, I mean, exact. It just feels a little precious for me.

Another person who's been bringing performance art into the mainstream is Lady Gaga. What do you think about her?

She makes me laugh my head off, and I love that. Is it really good art? I don't know. But I think that anybody who breaks the boundaries, I'm interested in. We'll see where she goes with it, because right now it's kind of Fellini stuff. She's a lot of fun, but I've never had my heart broken. That's what I'm always looking for.

Shares