It was found in attics and closets. It was drawn on ledger pages at turn-of-the-century mental institutions, made at tables in day treatment centers, and put together after a day's work at the factory from junk scavenged from dumpsters.

It was found in attics and closets. It was drawn on ledger pages at turn-of-the-century mental institutions, made at tables in day treatment centers, and put together after a day's work at the factory from junk scavenged from dumpsters.

It's called Art Brut -- a term coined by Jean Dubuffet -- raw art, survivor art, visionary art, vernacular art and outsider art, and it encompasses painting, drawing, sculpture, collage, assemblage and every kind of craft. But, as I learned recently, the term doesn't refer to a particular medium, technique or style. It's about the artists who make it: People outside the mainstream of society. They are or were (many were "discovered" years after their death) disenfranchised, institutionalized and almost always self-taught. A few may have taken drawing classes, but none has an MFA or formal academic training; they are outsiders to the fine-art world. Paradoxically, their work is becoming increasingly valuable, sought after by collectors, and has an annual home in New York at the Outsider Art Fair, at which 34 galleries from Europe, the Caribbean and across North America exhibited from Feb. 10 to 14.

Many of the artists, like graphic designers and illustrators, combine words with images to tell their stories, mixing painting and drawing with hand lettering, handwriting, calligraphy and the typography on found objects like signs and nameplates. Take a look:

Jesse Howard ^

Known as the crazy old junk collector of Calloway County, Mo., Howard died in 2003 at age 98. A self-styled painter of signs, he zealously and repetitively proclaimed his opinions in large block letters. A newspaper reporter who visited him two years before his death wrote, "Amidst the old tires and refrigerators, broken wagons and rusted farm implements, everywhere you look there are signs. They are hung on gates and fences, propped against buildings, nailed to anything that doesn't move."

William Rice Rode ^

Five works by Rode were discovered in a closet 100 years after the artist's death by the descendants of the superintendent of an Illinois mental hospital. He drew in colored pencil and ink on linen fabric, his stream-of-conscious recollections and Leonardo-like inventions surrounded by beautiful hand lettering and Spencerian calligraphy. To excerpt from the artist's bio on the website of Carl Hammer Gallery in Chicago: "Rode demonstrates a most incredible talent and an extraordinary level of self-taught genius. His life is visually self-documented, recalling experiences both outside and within the insane-asylum world from the late 19th century to the early 20th."

Dwight Mackintosh ^

Mackintosh, who died in 1999, believed he had X-ray vision. After spending more than 55 years in institutions, he began making art at the Creative Growth Art Center, an Oakland, Calif., a community center with the mission of nurturing and promoting the art of people with mental, physical and developmental disabilities. "This work comes out of an authentic need," explained Olivia Rogers of Creative Growth. "Sometimes the artists start making art after abuse or a trauma. They may be autistic or suffering from post-traumatic stress syndrome. Obsession is a mark of it. So is repetition of language. They usually don't care what happens to their art when it leaves their table."

Andrew Blythe ^

Perhaps "no" was a word this man heard too many times in his life. "What I'm doing now is trying to work with tones," says Blythe, a New Zealander who describes in this video how he makes art while suffering from paranoid schizophrenia. His work is represented by Creative Growth, which also promotes the work of outsider artists from France and New Zealand.

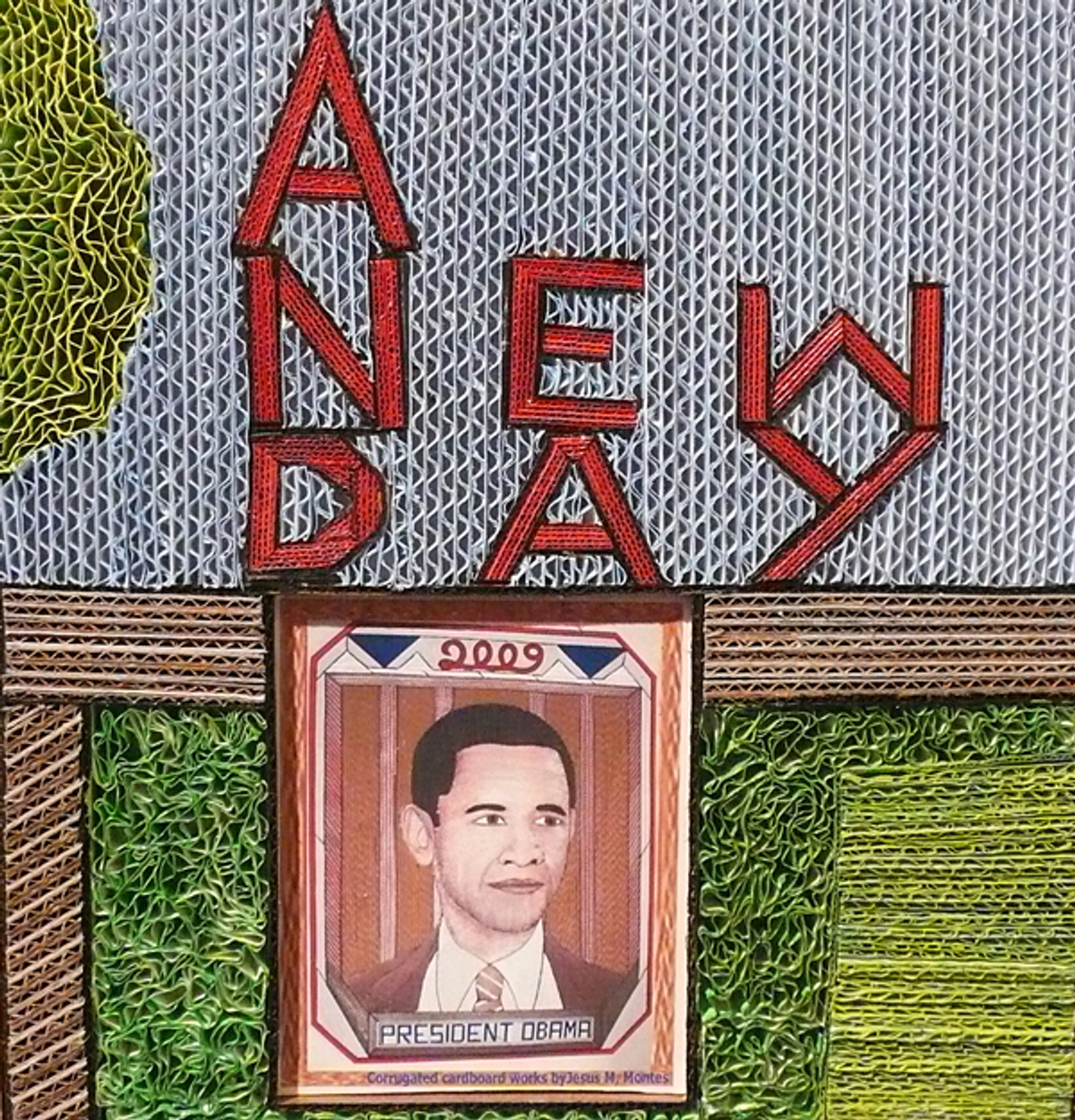

Jesus (Jessie) Montes ^

If there was one piece in this show I'd like to own, it's "A New Day" by Montes, an immigrant from Mexico, now retired school custodian, who creates scenes and portraits from recycled corrugated boxes, cutting and painting the edges to achieve varied textures. According to his gallery, Grey Carter Objects of Art in McLean, Va., "Jessie turned to art late in life to free his mind from concern about his two children involved in the first Gulf War ... he considers each work "a vision from God."

Electric Pencil ^

"Around the year 1900, a patient at State Lunatic Asylum #3 in Nevada, MO, who called himself The Electric Pencil executed 283 drawings in ink, pencil, crayon, and colored pencil." So reads the text on the home page of the site dedicated to his work. The drawings, which were found in a dumpster in 1970, were done on both sides of 140 hospital ledger pages. Gallery owner Evan Akselrad is searching for clues to the artist's identity.

Mies van der Perk ^

"Mr. Van de Perk works in our studio for talented artists with an ex-psychiatric backgrounds," explained Frits Gronert of Galerie Atelier Herenplaats, Rotterdam. Does it represent a financial chart or writing in blood? "It's a crazy world," said Gronert, who translated the text as, "Let it go through your fingers streaming in your heart."

George Widener ^

Elenore Weber of Ricco/Maresca Gallery in New York defined Widener, one of the most widely collected living outsider artists, as "a high-functioning savant" and a "lightning calculator." His bio reads: "Like some people with aspergers, he is gifted in dates, numbers, and drawing. In his memory, he has several thousand historical dates, thousands of calendars, and more than a thousand census statistics." This drawing, done on tea-stained paper napkins glued together, was made for future robots to refer to happenings in the year 4421. The Science Discovery Channel recently produced a 30-minute documentary on Widener, which includes interviews with the artist, collectors and a doctor from Columbia University's neurology department who has been studying and mapping his brain.

Felipe Jesus Consalvos ^

Consalvos was a Cuban-American cigar roller. He made more than 800 collages from cigar bands and cigar-box paper, magazine images, family photographs, postage stamps and other ephemera. They were discovered in 1983 -- more than 20 years after his death -- at a Philadelphia garage sale and are now represented by Andrew Edlin Gallery, New York.

Leo Sewell ^

"Leo gathers," said Emily Christensen of Outsider Folk Art Gallery in Reading, Pa. "His work is about bones, flesh and skin," she said, pointing out how every layer of his animals and human torsos is crafted from things he finds at flea markets and yard sales, in dumpsters and on the street.

David McNally ^

Worthy of contemplation: McNally, who calls himself "Big Dutch," notes in his artist's statement that he relaxes after a day's work in a Pennsylvania steel mill by drawing and painting in colored pencil, acrylics and watercolor. He is also represented by Outsider Folk Art Gallery.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

My wanderings around the fair led to many discussions with dealers about the nature of art, mental illness and outsider-ness. Are you still an outsider when your work is collected, TV networks do documentaries about you, and you show in New York? Weren't all the Impressionists who exhibited in the Salon des Refusés in 1863 outsiders at the time? Would many luminaries of art history who lived in a world before day treatment centers be classified today as mentally disabled? One gallery owner told me, "You're not an outsider anymore when you realize that your work is worth money." I didn't see anything priced at less than $400, and many of the works shown here sold for $15,000 to $60,000. That was the fair's biggest contradiction. And yet it was the most remarkable thing about it. You don't have to be -- [fill in the blank] for your work to be valued.

Salon is proud to feature content from Imprint, the fastest-growing design community on the Web. Brought to you by Print magazine, America's oldest and most trusted design voice, Imprint features some of the biggest names in the industry covering visual culture from every angle. Imprint advances and expands the design conversation, providing fresh daily content to the community (and now to Salon.com!), sparking conversation, competition, criticism, and passion among its members.

Shares