Like so many depressive, creative, extremely lazy high-school students, I was saved by English class. I struggled with math and had no interest in sports. Science I found interesting, but it required studying. I attended a middling high school in central Virginia in the mid-'90s, so there were no lofty electives to stoke my artistic sensibility -- no A.P. art history or African-American studies or language courses in Mandarin or Portuguese. I lived for English, for reading. I spent so much of my adolescence feeling different and awkward, and those first canonical books I read, those first discoveries of Joyce, of Keats, of Sylvia Plath and Fitzgerald, were a revelation. Without them, I probably would have turned to hard drugs, or worse, one of those Young Life chapters so popular with my peers.

So I won't deny that I owe a debt to the traditional high-school English class, the class in which I first learned to read literature, to write about it and talk about it and recite it and love it. My English teachers were for the most part smart, thoughtful women who loved books and wanted to help other people learn to love them. Nothing, it seemed to me at the time, could make for a better class. Only now, a decade and a half later, after seven years of teaching college composition, have I started to consider the possibility that talking about classics might be a profound waste of time for the average high school student, the student who is college-bound but not particularly gifted in letters or inspired by the literary arts. I've begun to wonder if this typical high school English class, dividing its curriculum between standardized test preparation and the reading of canonical texts, might occupy a central place in the creation of a generation of college students who, simply put, cannot write.

For years now, teaching composition at state universities and liberal arts colleges and community colleges as well, I've puzzled over these high-school graduates and their shocking deficits. I've sat at my desk, a stack of their two-to-three-page papers before me, and felt overwhelmed to the point of physical paralysis by all the things they don't know how to do when it comes to written communication in the English language, all the basic skills that surely they will need to master if they are to have a chance at succeeding in any post-secondary course of study.

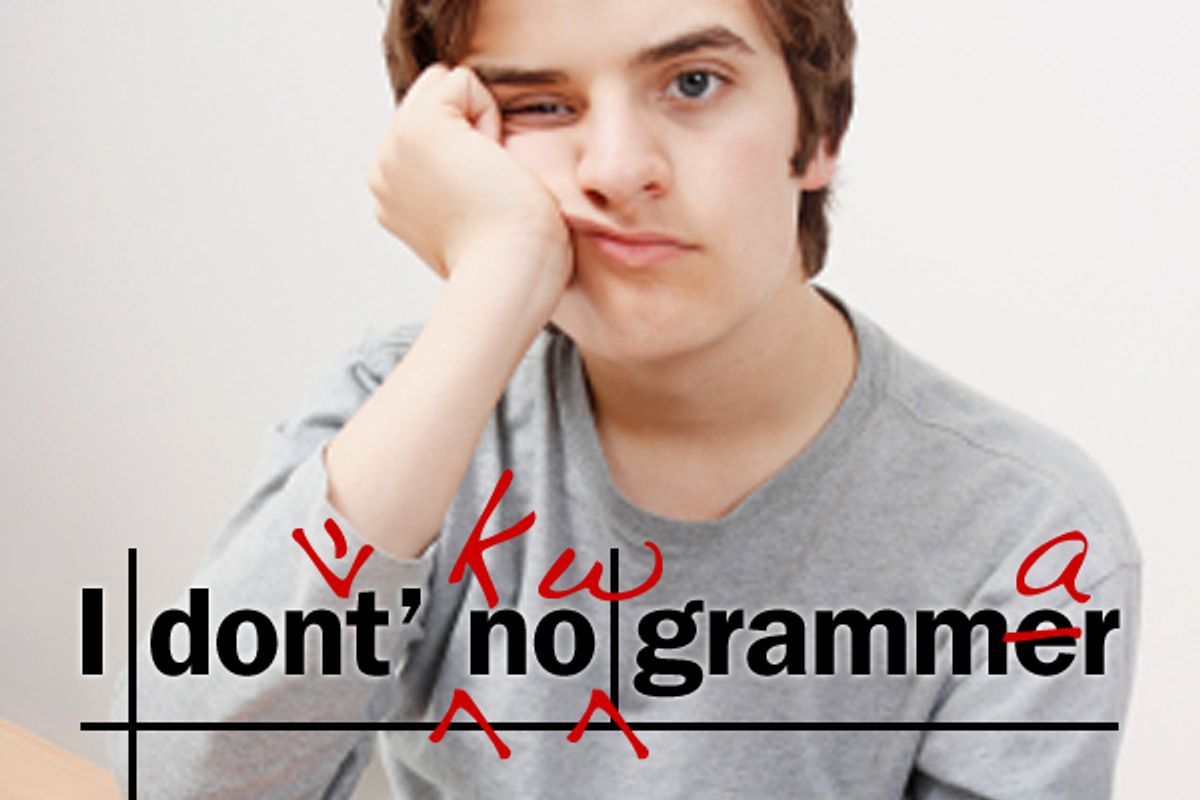

I've stared at the black markings on the page until my vision blurred, chronicling and triaging the maneuvers I will need to teach them in 14 short weeks: how to make sure their sentences contain a subject and a verb, how to organize their paragraphs around a main idea, how to write a working thesis statement or any kind of thesis statement at all. They don't know how to outline or how to organize a paper before they begin. They don't know how to edit or proofread it once they've finished. They plagiarize, often inadvertently, and I find myself, at least for a moment, relieved by these sentence- or paragraph-long reprieves from their migraine-inducing, quasi-incomprehensible prose.

Sometimes, in the midst of this grading, I cry. Not real tears, exactly -- more a spontaneous, guttural sob, often loud and unpleasant enough to startle my husband or children. There's just too damned much they need to learn in such a short period of time. It seems almost too late before we've begun.

And so recently, I've started asking them: "What exactly did you do in high-school English class?" And whether I ask them as a group or individually, whether I ask my best students or my worst, the answers I get are less than reassuring. I should add here that my students matriculate from a wide array of schools, everything from expensive prep schools and Midwestern publics, to military academies and boarding schools abroad. But despite this diversity, the answers I get from them about their preparation in the language arts are surprisingly similar.

Those who didn't make it onto the honors or A.P. track hardly mention writing or reading at all. They talk about giving oral presentations and keeping reading journals evaluated with a big, meaningless check. They reveal putting on skits, reenacting some scene in a novel or play whose title they can't recall. One student recounts a month of junior English class in which she and her classmates produced digital short film adaptations of the trial in "The Scarlet Letter."

"Sounds fun," I say to this student, a girl who would not know how to summarize a source or correct a sentence fragment if her life depended on it.

As for the students who did make it to more accelerated English courses, their recollections are a little less disheartening, but only a little. They read Shakespeare, they tell me, usually "Romeo and Juliet," sometimes "Macbeth." They read "Catcher in the Rye" or "Huck Finn," "The Sound and the Fury," a little Melville or Hardy. They read these works and then they talked about them in class discussions or small groups, and then they composed an essay on the subject, received a grade, and moved on to the next masterpiece. Did their exposure to a few of the great works challenge or change them, did it spur them to read more widely or more critically, or did it make them better writers? Occasionally, I guess. Mostly, they seem to recall struggling with comprehension of these classics, feeling as though they just didn't "get it," and for those students who know they will not major in English, does it really matter, they wonder. But not much time is spent pondering the question because, now, thrown into the cauldron of college-level coursework, they have bigger fish to fry. They have professors in every area and every discipline telling them they're going to fail if they don't learn how to write a comprehensible, grammatical and at least marginally organized academic essay.

Was it really so essential that these students read Faulkner? Most of them, frankly, seem to struggle with plain old contemporary prose, the level of writing one might find in, say, the New Yorker. Wouldn't they have been better off, or at least better prepared for the type of college work most will take on (pre-professional, that is), learning to support an argument or use a comma?

I raised these questions with Mark Onuscheck, the chairman of the English department at Evanston Township High School, a large, suburban school with a diverse student body and an excellent reputation, a school that's matriculated more than a few students into my classroom. I asked him how exactly a school like his teaches or tries to teach kids to write, and his initial answers make me start chewing on my nails. He talks about processes and collaboration, about students working together and doing peer review, about how they keep writing folders, and do writing frequently in various, informal ways.

"But the writing they'll need to do in college won't be informal," I say. "And it won't be reviewed by peers but by professors. So what about specific writing and research skills? What about style and grammar?"

Almost instantly, his tone shifts from one of back-patting, pedagogy-speak to something more honest. He laughs. "It's very hard to get a lot of teachers to teach those things, especially grammar. We have such a need to engage students. There's such an emphasis on keeping student enthusiasm going and getting them to want to actively participate. When you start talking about grammar, it's like asking them to eat their vegetables, and no one wants to ask them to do that. They prefer class discussion, which is great but to a certain degree, goes off into the wind."

And of course, there's also the logistical issue, the almost insurmountable challenge of teacher-to-student ratios, miserable ratios that are only going to get more miserable in light of the devastating teacher layoffs taking place around the country. At this particular school, every English teacher teaches five sections of English, and each section has approximately 25 students -- a dream load compared to what teachers at, say, a Chicago public face. But that still means a three-page formal essay assignment would translate into 375 pages of student prose to be read, critiqued and evaluated. The very thought makes a cold, dark dread creep across my soul. It makes my own burden, two sections of composition, 15 students to a class, seem laughably light. And yet, to my more successful, tenured friends, even my numbers seem grueling. One of them says flatly, "I'd teach four sections of lit before I'd do one of comp. Four sections with my hands tied behind my back. It's just too much work."

So says a college professor getting 80 grand a year, summers off and the occasional sabbatical. Hearing this, it's hard to blame the overworked high-school instructors out in the trenches. It's hard to blame anyone for not wanting to teach writing, which, while it might not involve manual labor or public floggings, is hard, grueling work. Often it demands maximum effort for minimum payoff, headache-inducing attention to detail, wheelbarrows full of grading, revision after revision, conferences with teary-eyed students. Who wouldn't prefer to talk about books or stories or poems? Problem is, the hard, grueling work to be done doesn't go away. Ask any college composition teacher.

I wonder at times, is it even worth it? Do students really need to learn to write?

I bounce the question off another friend, Amelia Shapiro, a longtime writing tutor and composition professor who now directs support services at a university in Hawaii.

"I hate that fucking question," she replies. "I hear it all the time and I hate it. No one asks this question about calculus, but who uses calculus besides math majors? If the question's going to be asked about writing it should be asked about every subject. Even students who aren't going to stay in college need to know how to write. We've all gotten emails or cover letters where we've judged people based on the writing. It's not an essay but it's still communication and people fail at it all the time in profound and meaningful ways."

When I ask her why she thinks there's such resistance to prioritizing and teaching writing, given its numerous applications, given its overlap with critical thinking skills, analytical skills, basic communication skills, she hesitates for a moment, then answers in three words: "It's not fun."

True, but then, teaching (and for that matter, learning) isn't always fun. Changing my kid's dirty diapers isn't fun. Dragging my fat ass onto a treadmill isn't fun. Helping my grandmother "fix" her computer isn't fun. Sometimes we do things not because they're fun but because they're important.

Each year, about this point in the semester, the point when I've decided that I will never teach composition again, that it's just too damned frustrating, that I'd rather be focusing on my novel, or reading my favorite writers, writers who make it look so easy, so seamless -- the point at which I think, life's too short; I'd rather be spending time with my family, or watching cable television, or doing absolutely anything but teaching composition, the point at which I would rather remove my own molars with a pair of garden shears than grade another paper, a student will stop by my office or catch me after class, not to tell me I've changed her life or inspired her to write the great American novel, but that, thanks to me, and the hours she herself has put in, she feels as though, in some small way, her writing has improved, or that she knows what she needs to do to improve, or that she can at least envision a future in which she is a better, more confident and more forceful writer of prose, and I tell her that no matter what, no matter how hard it is, she has to keep plowing ahead, because slow but steady progress as a reward for hard work is one of the few things we can count on in this life -- if we're lucky, that is -- and then I tell myself the same.

Shares