There was a time when chocolate was an artisanal product created by small European chocolate makers. Craftsmen used cocoa beans gathered from the spoils of their cacao-rich colonial empires in the Americas, and then Africa and Asia, where they'd transplanted the favored crop. But that time has come and gone. With the industrial revolution, the chocolate industry grew in size and complexity and the chocolate-making process became more refined; large companies rose to dominate the market and still do today. Americans may spend more than $15 billion each year on the food of gods and mortals -- but 80 percent of those sweets are purchased from one of the two mega-candy conglomerates that bully the market: Hershey's and Mars.

But maybe you're one of the few consumers who seek out organic, fair-trade chocolate, maybe a Nibs 68% made by Dagoba Organic Chocolate, a small, award-winning American premium chocolate producer. Sorry, but even then you're out of luck. Last fall, Dagoba was bought by the Artisan Confections Co., a wholly owned subsidiary of Hershey's that was created as a shelter for fine dark chocolate companies. And Scharffen Berger -- another once-independent chocolate maker -- was purchased not long before that. Who's left?

Today most small chocolate companies are nothing more than chocolatiers: outfits that buy ready-made couverture (refined chocolate that has gone through the first stages of processing) in bulk and use their own molds and branded packaging to claim it as their own. "Very, very few chocolatiers make their own chocolate," writes David Lebovitz, the former pastry chef at Chez Panisse and author of "The Great Book of Chocolate," on his blog. "I never believe anyone who says they're making their own chocolate unless they have some documentation to back it up, or I can see it being made."

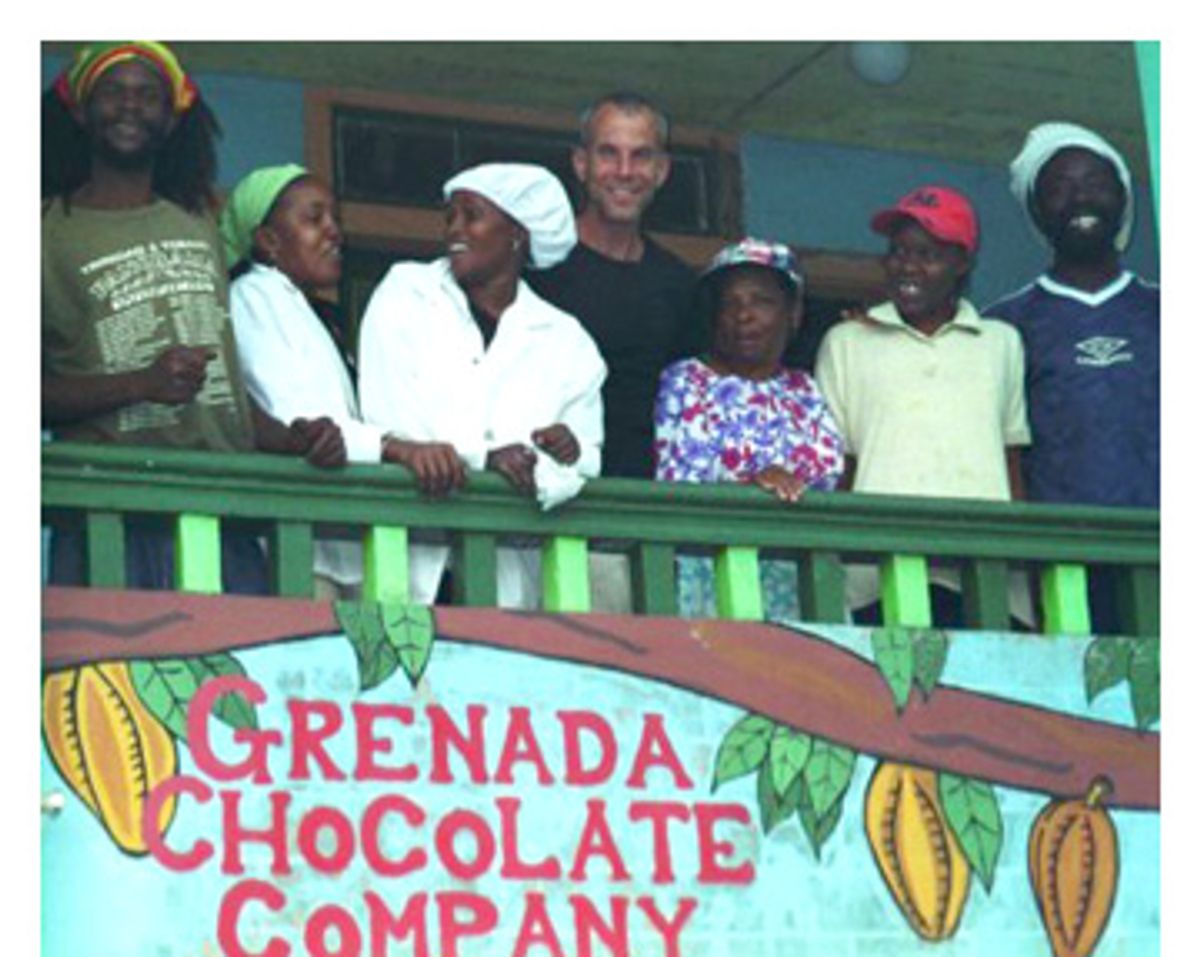

I've seen chocolate being made. From the swing of a machete to the cleaving of the squashlike pod -- revealing soft white beans covered in a tasty white goo -- to the final delicate tempering. The Grenada Chocolate Co., a homegrown operation on the small island of Grenada, deep down in the West Indies, makes its own chocolate in a house-turned-factory painted in a palette of tropical pastels. Solar panels cover the roof and overflow into the yard. Across the one winding street that defines the small village of Hermitage, a white hand-painted sign on a piece of board points to "slave pen alley," and an abandoned plantation complete with slave barrack, now overgrown with jungle. The factory's cocoa beans are grown organically a few kilometers away. Two of the three founders live on the island and work cooperatively with a handful of workers, all locals.

Edmond Brown, one of the owners of Grenada Chocolate, sits on a set of concrete steps outside of the factory. "I like making chocolate because I like the work," he says in a thick Grenadian accent, swatting at sand flies and stressing the last word to show his deepest respect for the human undertaking of doing something tangible with one's hands. He is a man who tends to speak only when there is something worth saying, yet Brown becomes animated when talking about chocolate, "the organic chocolate," as he calls it. His partner, Doug Browne, is a lanky, gentle 6-foot-7 giant, who now spends most of the year in rural Oregon. In the eyes of the islanders, Doug bears a striking resemblance to Jesus.

Mott Green completes the trio, and he is the talker, the dreamer, the man who first envisioned a Grenadian chocolate company. A sinewy American with a closely shaved head, Green lives in one small, spartan room in the corner of the factory, and exudes kinetic energy, as though he never sleeps. Originally from New York, he describes himself as an "ex-tourist instead of an expatriate." Green has lived in Grenada on and off for more than 20 years, whenever he wasn't hopping rail cars between his other bases in New York and Philadelphia squats or staying with friends in Oregon. It was in Oregon that Green and Browne met, and over the course of their friendship the two developed a taste for tinkering: transforming a Volkswagen squareback into an electric car and building a 20-foot-high solar steam generator, the remains of which reached up into the sky on Browne's Oregon farm for years after the experiment, like some alien communication device.

Browne, Green and Brown make an unlikely business team, with ambitious ideals about every step of production for their chocolate. But their dark (and darker) Grenada Chocolate bars -- 60 percent or 71 percent cacao content, no milk, no nuts, no fruit -- and Smilo cocoa powder are earning accolades. In 2006, they received a World Chocolate Award from London's Academy of Chocolate and were declared "the world's finest, and rarest, chocolate" in the Guardian. Within the company's first year of production, in 2001, they unexpectedly sold out in the Grenada market and since then have only been able to produce enough to meet limited distribution in the United States and Europe, through online outlets and in select shops.

But all that is changing. The co-owners are in the process of replacing their manufacturing infrastructure in order to increase the company's batch size from 45 kilos to 250 kilos. For now the Grenada Chocolate Co. may well be the smallest, most politically correct chocolate factory on earth. But does it have a future in a Hershey world?

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Grenada is known as a "Spice Island" thanks to its production of nutmeg, mace and the cocoa beans that are the key ingredient in chocolate. Green first came to the island as a 15-year-old kid, accompanying his doctor dad on trips from New York to the medical school on the island capital of St. Georges. Green watched the plump cacao pods turn shades of yellow, orange and red as they grew straight from the trunks and branches of the understory trees. He learned that some of the world best trinitario beans grew there, were picked by the dark hands of the islanders, fermented in burlap sacks, turned by native feet to dry under a tropical sun, and then shipped off to far-flung places. Off there, in the first-world nations, enormous expensive machines transformed the Grenadians' raw product into Hershey and Cadbury bars, then packaged and sold them back to Grenada and the rest of the world.

With that realization a different idea -- a question really -- began floating around Green's head, vague and undefined. What if someone made chocolate there, so Grenadians could eat chocolate from their own cocoa beans? The self-proclaimed anarchist imagined starting his own business: a chocolate company from the bean up.

In early 1999, Browne went to visit Green on Grenada, and that vague idea, then decades old, began to take on a concrete shape. As Browne remembers it, the two were sitting in Green's hand-built bamboo hut -- a creaking, leaning, sievelike structure perched on a steep mountainside -- drinking local unrefined cocoa, when they decided together to try and make a go of it as chocolate makers. Browne agreed to invest some of his own money; when the two Americans asked their friend Edmond Brown to join them, the trio was formed.

The ideals of the company were both simple and lofty. All three founders were in their mid-30s. They believed in the human right to have dominion over one's life: Each had worked to make that a reality for himself, and if they had anything to do with it, for others. They swore there would be no compromise in the making of great chocolate. It would be organic, locally grown and produced. Farmers would be paid decent wages and the company would be cooperatively structured. The factory would run on solar power and a sailboat would deliver the finished product throughout the Caribbean. Everything they could do, they would do. The Grenada Chocolate Co. was born.

Full disclosure: I first met Browne and Green through Aprovecho, a sustainable living and alternative technology research center in Oregon, where I lived and worked in the late 1990s. Browne lived down the road on 20 acres and Mott Green showed up in town now and again, usually unannounced. Both were regular visitors to Aprovecho and occasional guest lecturers, and when a living space became available in Browne's renovated barn in 1999, just as their chocolate company was beginning, my boyfriend and I moved in. Green arrived at Browne's Oregon homestead that autumn bearing burlap sacks filled with cocoa beans, and the pair set up a proto-factory on the first floor of the barn. Building the machinery needed to make chocolate -- a roaster, a winnower, a mélangeur, a conch and more -- required easy access to parts and a good metal shop. They decided to create the guts of the factory in the U.S., then ship the whole thing down to Grenada.

For a few delicious months life was one big chocolate experiment. We chiseled away at chocolate mountains that were a relief of the five-gallon buckets used as holding containers. We slurped from a messy pot of cocoa, always topped off and rarely washed, that had assumed a permanent position on the stovetop. I fell asleep to the lullaby of the conch rollers methodically grinding the cocoa into a thick, dark liquid, the intoxicating smell of chocolate filling the air.

In March of 2000, the team filled a giant shipping container with their factory machines and sent it across the continent and the Caribbean to Grenada. There, they set up the equipment and continued to refine the machinery until -- a year and a half later -- Green, Brown and Browne were making chocolate on the island with local organic beans. Good chocolate. They replaced some of their hand-built machines with small-scale food machinery -- a nut roaster from Texas, a Swiss grinder once used for sesame seeds -- as well as vintage chocolate equipment including a winnower from a factory in Jamaica and a mélangeur built in Dresden in the 1930s. By 2002, they'd been certified organic and were selling out their run of 1,200 bars a week in Grenada. And then there was a storm.

Grenada doesn't get hurricanes, just warnings. At least that was the conventional wisdom before Hurricane Ivan ripped across the island on Sept. 7, 2004, bringing winds of 115 mph, damaging more than 90 percent of the buildings on the island, killing 28 and leaving thousands homeless. After six hours, the storm continued northward, securing its place in the record books as the most devastating hurricane to hit Grenada since 1955.

The next summer, Hurricane Emily hit -- and it's been a long slow road to recovery ever since. After the storms, the Grenada Chocolate Co. focused on rebuilding and expanding. The owners fortified the factory's roof, increased their solar panel capacity to 6.7 kilowatts and bought a diesel generator that can be run on bio-diesel. They began working to help local farmers become certified organic and ordered more equipment from Europe -- including a refiner from Scotland and an Italian tempering machine -- that would quintuple their batch size and finally make shipments into the world market financially viable.

But while buildings can be rebuilt in a hurry, cacao plants take their own sweet organic time. As the Grenadian crop recovers, the company has had to temporarily supplement its supply with cocoa from Costa Rica -- and only time will reveal whether a changing climate will mean more and more hurricanes in Grenada's future. If a steady supply of certified organic cocoa becomes increasingly difficult to obtain, it could mean big trouble for both this little company as well as larger operations in other parts of the world.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

In the space of six years, Grenada Chocolate has evolved from a flight of fancy to a successful business -- but along the way, concessions have, of course, been made. While the company works cooperatively with Belmont Estates, the local farm that exclusively grows its cocoa, they have not been fair trade-certified. According to Green, it's more than procrastination that's kept them from filing the paperwork: Fair-trade chocolate companies still, almost exclusively, process the value-added product in the first world with raw materials they import from the equatorial belt where cocoa grows. In that way, even the fair-trade system perpetuates a cycle the founders of the Grenada Chocolate Co. are determined to break. "They're buying cocoa from the south part of the world to bring it to the north part of the world," Green said. "But what we're doing can effectively make sure that the people doing the work are actually part of the process." It's bean-to-bar. It's single-estate. Farmers earn a living wage.

Legally, the Grenada Chocolate Co. has become a company, not a cooperative, though it is still run with that spirit. Green bought a sailboat, still intent on using it for delivery -- but it's not yet seaworthy. Instead, chocolate is delivered in a little blue Suzuki van around the island and by plane in small but expensive batches to European and American distributors. And there's even talk of reviving that old electric VW squareback that Green and Browne retrofitted for New York City distribution.

There have been no calls from Hershey's. Yet. But this year, when the Grenada Chocolate Co. increases its production, elbowing into a gourmet chocolate market that is growing at 28 percent a year compared to the 2-3 percent growth of the conventional chocolate market -- well, what then?

Dagoba offers an instructive case study. Started around the same time as the Grenada Chocolate Co., the Oregon-based Dagoba began and was also built on an ideal of "full circle sustainability." After five years, the company was so successful -- selling an estimated 7 million candy bars and earning $9 million in 2006 -- that it was bought out by a subsidiary of Hershey's in the fall of 2006. I asked Dagoba's founder, Frederick Schilling, about the state of the company under the new ownership. "The biggest drawback for me is the lack of trust expressed by our fans," he said. But, Schilling admitted, he couldn't blame them. "The past is littered with stories of larger companies buying smaller ones and turning their products to crap." Fundamentally, though, Schilling insists that he didn't intend for Dagoba to forever be an independent. "I wanted to use it as a vehicle of change ... Things are changing so fast these days that large companies have to embrace sustainability initiatives and fair labor practices or they're going to fail."

I asked Browne what he thought about the recent conglomeration of independent chocolate companies. "Sharffen Berger took me by surprise," he said, "but when Dagoba happened, it didn't surprise me. I just know how voracious [Hershey's and Mars] are -- about anything that could marginally be considered candy in the United States. They just snap up everything."

Ever the optimist, Browne remains hopeful about the fate of his own enterprise. "We'll always be small. We'll always be a bit of a niche product, but if anything, having Hershey's buy out companies might make a better market for us," he explained. After all, "there are a lot of people out there who are looking for the small, independent businesses and down-to-earth products as opposed to the ones that are multinational."

Shares